Agricultural advisory services - what will they look like in 2020?

Author: Mick Keogh | Date: 19 Mar 2014

Mick Keogh,

Australian Farm Institute.

Take home messages

- Historically agricultural advisory services have been delivered by government agencies; however this has changed with more than 2,300 private sector crop advisers spread across all states.

- The changing landscape also includes a shrinking population of crop farm businesses and increased regulation and compliance.

- Increased use and capacity of technology will impact the future of agricultural advisory services; with 'recipe farming' fast developing oversees.

- An opportunity for advisers appears to be in adding value to remote sensing technology, computerised decision support tools and variable rate technology by integrating the available data and information into something that is relatively simple, straightforward and usable by farmers.

- Individual crop advisers can to some degree choose their own future, either adopting new ideas and developing new systems or doing things as they have always done.

Introduction

Projecting what something will be like even five years into the future can be a dangerous business given the rate of change in telecommunications and technology in our modern world.

This really hits home when you realise that it was only on June 29th 2007, that the first iPhone was launched by Apple. A little over five years later, that single piece of technology, and its subsequent imitators, has dramatically changed the way that the world communicates, is entertained and obtains information. If anyone had predicted at the time that by the end of 2013 there would be almost 1.5 billion iPhone users worldwide, and many more users of similar 'smart' technology, they would have been dismissed as mad, but that is a reality today.

While statistics about the growth in the number of iPhone users globally might be interesting, it may not immediately be apparent why that particular statistic is relevant to the future of agricultural advisory services in Australia.

The reason I think it is relevant is that agricultural advisory services are, at their core, about the delivery and exchange of information. Therefore, technological changes in the way information can be collected and exchanged will inevitably mean changes in a whole range of business advisory services, including those associated with farm businesses.

This paper aims to try and project what farm advisory services might look like in the future. It commences with a brief look at the history of farm advisory services in Australia, both public and private, before looking at some of the major trends that are likely to impact on farming and related advisory services. The paper concludes with some observations about how farm advisory services might be optimised in the future.

A brief history of Australian farm advisory services

Most Australian colonies established a Department of Agriculture of some sort prior to federation, with Queensland being the first colony to establish such an agency in 1859. When federation occurred and Australia became a nation, the constitution made no reference to agriculture as a responsibility of the Australian Government and hence it remained a state government responsibility.

In the early years of the 1900s, agriculture was seen as a key driver of economic development and growth and government agricultural departments had considerable power and resources. Their main functions included agricultural research, biosecurity and the provision of advice to farmers. Many of the major developments that dramatically boosted Australian agricultural production in the second half of the 1900s were the result of research and advisory activities by employees of these agencies.

These agencies retained their power and prestige through the two world wars when food and fibre became very important strategic commodities. This continued well into the 1970s. Government expenditure on agricultural agencies began to level off in the late 1970s and has largely been static or declining in real terms since that time.

State government expenditure on agricultural agencies actually declined more rapidly than Australian Government expenditure, which to some extent is buffered by farmer levy revenue (set at a percentage of gross revenue) and matching tax payer contributions. The pressure on state government agricultural agency budgets led to serious questioning about which functions could be 'cut' and advisory services were generally considered more expendable than research or biosecurity services. Consequently, commencing with the Government of Western Australian in 1989, state governments have progressively removed the 'advisory' part of their state government agencies. At the very least, they have dramatically reduced and converted them to wholesale information providers, providing advice to advisors, rather than providing one-on-one advice to farmers.

Private sector advisory services have grown in Australia since that time, although to a different extent in the various commodity sectors. More intensive commodity sectors such as poultry, pork, some sectors of horticulture, cotton and grain seem to have a greater reliance on private advisers that the broadacre livestock sector, for example. Some sense of the dominance of private advisers can be gained from the fact that there are estimated to be approximately 85 full-time equivalent (FTE) personnel involved in grain advisory work in the public sector in Australia. In addition, there are more than 2,300 private sector crop advisers spread across all states. In fact, a recent survey revealed that approximately 70 per cent of all grain growers now employ an adviser.

Table 1. Estimated population and nature of employment of Australian crop advisers

|

State |

Retail advisers |

Independent advisers |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

ACT |

2 |

3 |

5 |

|

Northern NSW |

177 |

102 |

279 |

|

Southern NSW # |

318 |

141 |

459 |

|

Queensland |

166 |

89 |

255 |

|

Victoria |

365 |

183 |

548 |

|

South Australia |

434 |

172 |

606 |

|

Tasmania |

37 |

33 |

70 |

|

Western Australia. |

40 |

60 |

100 |

|

Total |

1,539 |

783 |

2,322 |

# Southern NSW is defined as the area south of the line from Orange to Dubbo and then west through Nyngan.

A recent survey of private sector crop advisers in Australia identified that approximately two thirds are retail advisers, working for a chemical, fertiliser or seed company or retail outlets. The rest are predominantly self-employed or work in a group of less than five advisers. The average age of these crop advisers is between 29 and 35 and they service an average of 40 clients with most located within 150 kilometres of their home base.

There is no reason to believe that the trend towards reliance on private sector advisory services in the grains industry is going to diminish, or that state governments are suddenly going to place a higher priority on funding agriculture departments. Consequently, Australian grain farmers will increasingly rely on private sector advisory services in the future.

Major future trends likely to impact advisory service providers

The Australian grains industry is in something of a unique position globally in relation to its reliance on a private advisory service. Therefore, there are only limited indicators available from overseas experiences of the development of private advisory services that are likely to be applicable here.

Most international grain sectors in developed nations have a growing reliance on private sector advisory services, although for a variety of different reasons. In Brazil, the large-scale grain and oilseed farmers of the central west are generally participants in cooperatives that supply inputs, provide advisory services and arrange the marketing of grain. Private sector crop advisers there are accredited by the Ministry of Agriculture and have to sign-off on annual crop plans before farmers can access concessional government loans.

In the USA, governments have maintained a very large land-grant university system for almost 150 years, which have a teaching, agricultural research and extension role in conjunction with state and county governments. The use of private sector crop advisers is almost universal in the corn belt, but is dramatically less prevalent in the wheat belt where public sector advisers still dominate.

In Denmark, there are no public sector advisers as such. The farmers union dominates agricultural research and extension, employing private sector crop advisers whose main role involves certifying annual crop and fertiliser plans for farmers, as well as providing fee-for-service on pasture and crop production. There are also a small number of private sector advisers employed by input supply companies.

In all three of the above nations, private sector crop advisers are certified and generally operate in larger cooperatives or groups employing up to fifty advisers, rather than as sole traders or in small groups. In Brazil and Denmark, their principal role is associated with compliance rather than advice, although they also put together crop 'packages' for farmers.

A notable feature of the advisory market in all three locations is the increasing use of electronic technology in the delivery of information and also as a means of capturing and reporting information.

In Denmark, there are very strict pesticide regulations, including the mandatory reporting of all pesticide use within seven days. Farmers have set up a compliance system to deal with this via a smartphone application that prompts for information about pesticide use each time the farmer enters a paddock which the smartphone detects via GPS coordinates. In Brazil, one of the major sugar producers monitors all their growing sugar via satellite and drone sensing. The interpretation and analysis of which is carried out centrally by the head crop adviser who instructs each of the twenty or so farm managers about what fertiliser or spray is needed and where.

In the USA, Monsanto is in the second year of trialling their FieldScriptsSM initiative, which some are referring to as 'recipe farming'. Under this system, farmers 'enrol' the fields they intend to plant to corn in the system, Monsanto accesses the relevant soil and climatic data for that particular location, then puts together a prescription for the crop. This includes seed varieties to use, planting spacing across the field, fertiliser and other inputs. The information is provided via an iPad application that is plugged into a precision planting variable rate planter in order to sow the crop according to the prescription. Subsequent yield data is used to refine the system in the following years. Other major bioscience companies have similar concepts either in the pipeline or under trial.

The development and use of computerised expert systems and decision support tools is one of the major changes occurring in cropping globally, all made possible by the development of smartphones, tablets and associated telecommunication networks. The development of these sorts of systems is really at a very early stage, but is progressing rapidly. For example, from an initial trial of 140 farms in 2013, FieldScriptsSM is now being offered across four US states in 2014. It goes without saying that these types of developments are likely to dramatically change the market for farm advisory services in the cropping industry over time and has significant implications for those currently providing advisory services to farmers.

A second issue changing the market for crop advisory services is the change occurring in the number and scale of farm businesses in Australia. It should come as no surprise to anyone that the number of farms in Australia has declined by almost 15 per cent over the past fifteen years, while the number of grain producing farms has declined by almost 25 per cent, Table 2.

Table 2. Number of Australian farm businesses

|

NSW |

VIC |

QLD |

SA |

WA |

TAS |

Australia |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

2011/12 |

||||||

|

Total farms |

38,875 |

29,141 |

25,262 |

12,556 |

11,170 |

3,486 |

120,980 |

|

Grain specialists |

3,613 |

2,631 |

1,475 |

2,667 |

2,661 |

6 |

13,053 |

|

Grain/livestock |

4,108 |

2,373 |

1,025 |

1,949 |

2,058 |

40 |

11,552 |

|

2005/06 |

|||||||

|

Total farms |

43,268 |

33,310 |

28,905 |

14,901 |

12,872 |

4,068 |

137,968 |

|

Grain specialists |

2,844 |

2,785 |

1,087 |

3,204 |

2,530 |

28 |

12,479 |

|

Grain/livestock |

5,619 |

2,800 |

1,172 |

2,386 |

2,798 |

66 |

14,843 |

|

2000/01 |

|||||||

|

Total farms |

41,421 |

34,885 |

29,397 |

15,246 |

13,288 |

4,197 |

138,917 |

|

Grain specialists |

4,364 |

3,198 |

1,590 |

4,220 |

2,908 |

32 |

16,314 |

|

Grain/livestock |

6,196 |

2,987 |

1,513 |

2,056 |

3,104 |

61 |

15,917 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statisics, 2013.

Over the same time, the average size of grain farms has increased dramatically with farms in Western Australia doubling in average size since 2000. Farms in the eastern states have grown by almost the same amount, although off a smaller initial average. This change has implications for crop advisers, given that farmers typically employ a single adviser for their entire farm.

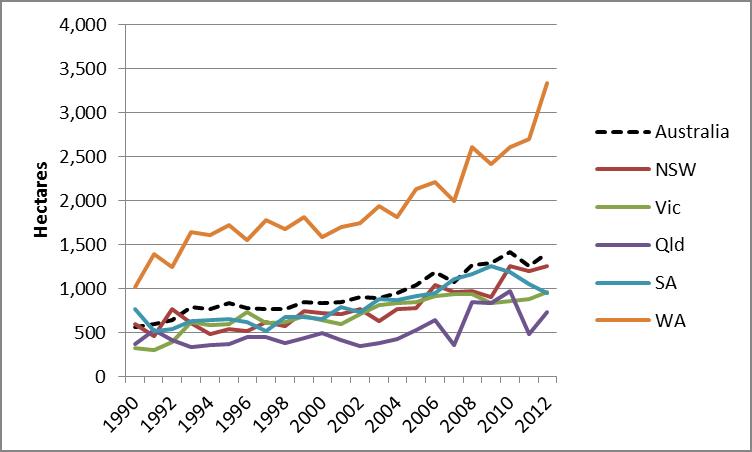

Figure 1 Average area of crop sown per farm. Source: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, AGSURF, 2013

A third issue I think is likely to change the market for farm advisory services over the next five years is the issue of 'compliance'. It is apparent in overseas locations such as Europe, and even Brazil, that the social licence available to farmers in relation to the use of technologies and farm inputs is being restricted by community concerns about their safety and implications. In Brazil, the compliance issues are associated with the retention of forest areas and the use of chemicals. In Europe, concerns are about the use of fertilisers and pesticides, while in the USA there are emerging concerns about stewardship arrangements associated with GM crops as well as the use of some pesticides and fertilisers in the proximity of waterways. Consequently, in all three of these locations a certification process has been developed for crop advisers. In Europe and Brazil the process is controlled by government, while in the USA the industry has established a system, Certified Crop Adviser, which is recognised by government.

Compliance is perhaps a less immediate issue in Australia, although the outcome of the Marsh vs Baxter case in Western Australia could change that. More generally, pressure applied in relation to pesticide use and the development of resistant weeds and insects will inevitably lead to more stringent requirements on crop inputs and technology use, with likely increased compliance requirements.

Implications for advisory service providers in 2020

The three changes noted above (the development of 'recipe farming'; the shrinking population of crop farm businesses; and the likely increases in regulations and compliance requirements) will undoubtedly alter the market for crop advisory services by 2020, albeit that recipe farming and compliance are likely to be less pronounced in Australia than they are in some overseas locations.

The use of remote sensing technology, computerised decision support tools and the growth in variable rate application technology will result in these systems increasingly making a lot of the decisions that, in the past, have been made by crop advisers.

This will undoubtedly mean that crop advisers either have to find ways to provide their services at less cost, in order to compete with technology, or find ways to ensure that their services add value to these systems.

The biggest opportunity to add value to these types of systems at the moment appears to be in integrating the available data and information into something that is relatively simple, straightforward and is usable by farmers. There is currently a very large and growing stock of yield maps and data sitting on farm computers that is not being used effectively, but which could form the basis of the next steps in crop productivity growth if integrated into useful decision support systems.

This obviously creates a considerable challenge for the Australian crop advisory industry, given that the majority of independent crop advisers work individually or in small groups. Developing the agronomic knowledge and skills necessary to be a good crop adviser is a challenge in itself, let alone developing computer and telecommunications knowhow to add value to the increasing volume of crop production data.

Internationally, it is much more common for crop advisers to work in organisations such as cooperatives that have anywhere from twenty to one hundred crop advisers employed. Groups such as this have the resources and capacity to develop technologies and expert systems that can be used by their advisers, something which is very difficult for smaller businesses. I suspect this means it will be increasingly difficult for individual advisers to maintain their businesses without at least developing some close alliances with other advisers or becoming a part of a larger group of advisers that can share technology and information.

Finally, compliance issues are likely to continue to grow and ultimately lead to the need to 'professionalise' the role of crop advisers. Internationally, this has happened either by governments regulating the advisory industry and imposing certification requirements, or in the case of the USA, the 'industry' developing its own certification system and convincing regulators that they can rely on the system. This is likely to be a growing issue for crop advisors in Australia, both retail and independent advisors, and one which the industry will need to address sooner rather than later.

Conclusion

In conclusion, crop advisory services are very much like farming. Individuals involved can to some degree choose their own future, either adopting new ideas and developing new systems or doing things as they have always done. The former is not necessarily a guaranteed way to achieve future success, but it at least provides some chance. The latter is a sure way to steadily become less successful and relevant over time.

Contact details

Mick Keogh

Australian Farm Institute

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK