Decision making during the cropping season - spring is still the key!

Author: Peter Hooper | Date: 12 Mar 2014

Peter Hooper,

Hooper Consulting.

Take home messages

- Aim for an average season and adjust where possible.

- High input farming is not generally the most profitable strategy.

- Don’t spend it if you can’t afford to lose it, understand your ability to handle risk.

- Don’t aim to make money in the good years, instead avoid muck ups and minimise costs every year.

- Be prepared and do it on time.

Modern farming systems enjoy a greater range of tools to aid in decision making during the growing season. Importantly, growers now also have the technology to capitalise on these in-season decisions and create flexibility. The reliability and accuracy of short-term weather forecasts has improved immensely and also contributed to easier decision making.

While growers have flexibility and can make some adjustments during the growing season, this is rather limited. In reality, the main areas for change during the growing season simply include nitrogen fertiliser application, choice and amount of fungicide, use of growth regulant, level of crop insurance and amount of grain marketed.

There are a range of products and services to help with in-season decision making:

- simple historic rainfall and temperature deciles, such as Rainmain or CliMate;

- seasonal forecasting, such as SOI, IOD and ENSO;

- short term weather forecasts (a large range of websites and apps available);

- yield prediction tools and newsletters, such as Yield Prophet, Hart Beat, The Break; and

- soil moisture probes.

Further to these products, growers also have the ability to make variable rate input decisions based on paddock spatial variation through crop sensors mounted on tractors, satellite photos or other images collected from planes or UAVs and drones.

In 2013, these tools were very effective for applying more nitrogen to water logged or sandy areas of paddocks and less to the lush or bulky areas.

By early spring in 2013 there was an 80 per cent chance of harvesting an above average crop (good soil moisture and crop growth), yet the 20 per cent chance of a poor finish (frost, hot winds, dry spring) occurred, Table 1. It certainly highlights why high input farming is not always a successful or profitable strategy.

Table 1. The number of days per month a weather event occurs at Snowtown, Clare or Yunta SA, also shown as a percentage (%). The data is taken from the last 20 years of met station records

|

Weather |

Snowtown |

Clare |

Yunta |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Days |

% |

Days |

% |

Days |

% |

|

|

Days < 2oC September |

5.2 |

17 |

3.7 |

12 |

5.2 |

17 |

|

Days < 2oC October |

4.3 |

14 |

1 |

3 |

0.8 |

3 |

|

Days > 30oC September |

0.9 |

3 |

0.1 |

0.5 |

2.3 |

7 |

|

Days > 30oC October |

5.2 |

17 |

1.6 |

5 |

5.1 |

16 |

Most of the flexible farm decisions on inputs (mainly nitrogen fertiliser, fungicides and insecticides) are being made in late July and early August during early stem elongation. This is mainly driven by the frequency of rainfall fronts and stage of crop development.

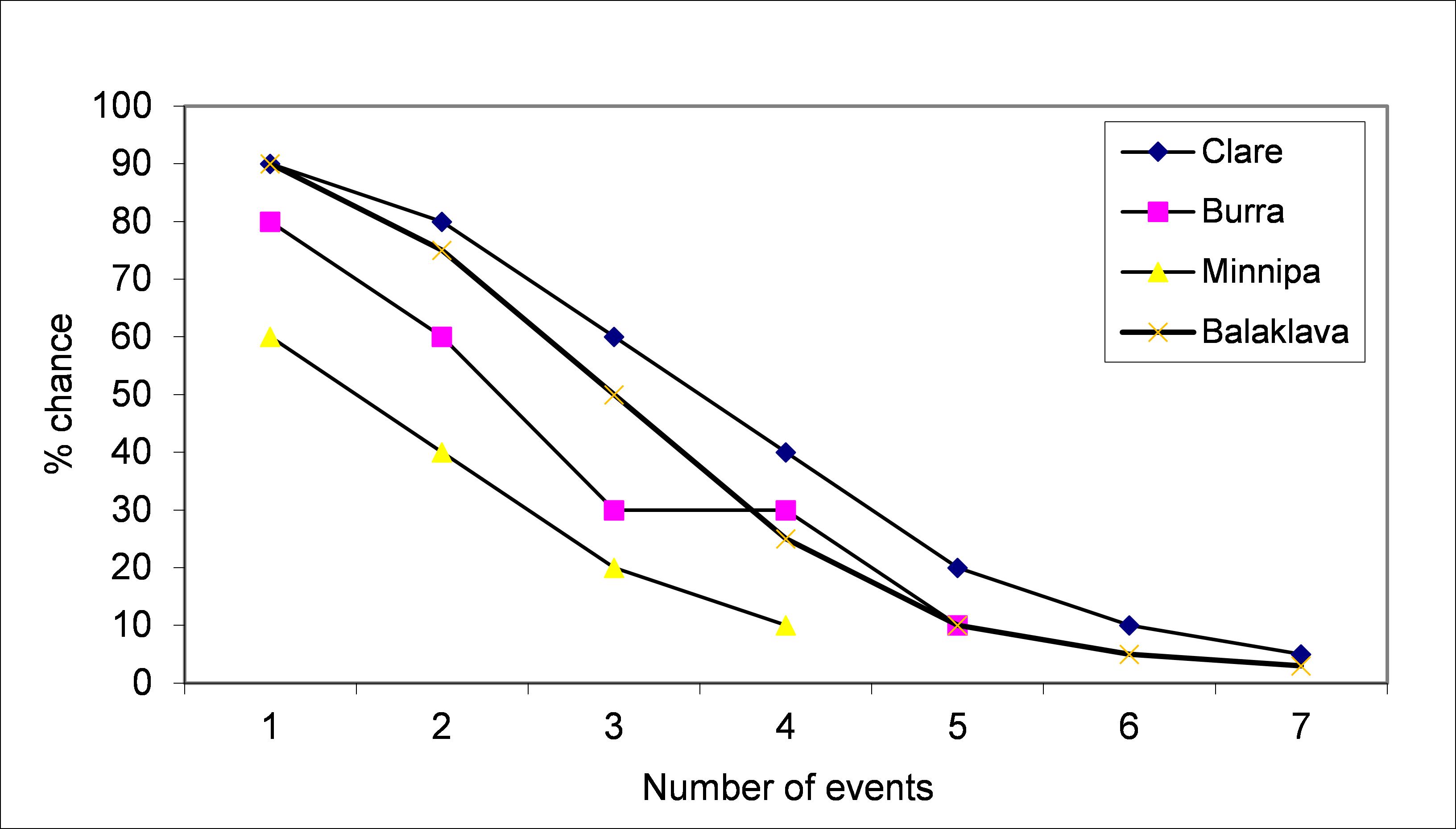

However, by August the opportunity to spread (or chance of rain) decreases rapidly and the logistics of managing large areas also becomes difficult, Figure 1.

Figure 1. The number of rainfall events greater than 10mm over 2 days in August, or 5mm in 1 day at Balaklava. Source: Rainman.

At this point in the year, growers have the ability to pick out the really wet or dry seasons and make the necessary management decisions. However, the season is very difficult to pick and the seasons at either end of the decile scale create easier scenarios compared to the uncertainty during average seasons.

The season potential is still relatively uncertain and, most importantly, spring is still the key.

Even with a very wet winter and full soil profile we rely on spring conditions to finish crops, specifically temperature. There are a number of studies available to the show the importance of temperature and grain yield. For example, Table 2 shows that for each degree above the average daily maximum temperature of 21.8oC during flowering, the decrease in grain yield can be 371 kg/ha, while a day above 35oC could result in a decrease of 837 kg/ha! At this crop stage, the impact of rainfall is negligible at 22 kg/ha for each millimetre.

Table 2. The effect of various climatic variables on grain yield across over 600 field experiments in southern Australia 2005-2010. The average grain yield across all trials was 2.53t/ha (Telfer, 2012)

|

Growth Stage |

Climatic Variable |

Unit |

Effect (kg/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Flowering |

Rainfall |

mm |

22 |

|

Average daily min temp (above 7.6oC) |

oC |

-161 |

|

|

Average daily max temp (above 21.8oC) |

oC |

-371 |

|

|

Days > 30 oC |

number |

-379 |

|

|

Average temp (above 14.7oC) |

oC |

-490 |

|

|

Days > 35 oC |

number |

-837 |

Summary

In many instances, decision making has become over complicated in an unpredictable environment; hence growers should aim for average and adjust where possible. We farm in a variable environment where spring is still absolutely vital.

Acknowledgement

Thankyou to Paul Telfer of Australian Grain Technologies for his data on climatic variables.

Contact details

Peter Hooper

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK