Analysing and discussing risk in farming businesses

Author: Cam Nicholson (Nicon Rural Services) | Date: 23 Mar 2015

Take home messages

- Farming is the most volatile sector of the Australian economy and by inference the most risky. To cope with this volatility many farmers have developed strategies for production and price variability so they remain in farming.

- Agricultural extension can take little credit for farmer’s current approach to risk management. Most farmers have developed risk strategies based on intuition and experience rather than on useful extension materials and knowledgeable advisory support.

- One component of the Grain and Graze 2 program is to support farmers, advisers and consultants to understand and discuss risk. A pilot program conducted in Southern Victoria has developed a risk analysis and discussion format to help farmers quantify the risk in their farming business (the risk profile) and then discuss the implications of the results.

- This paper presents the approach used and feedback from farmers, advisers and bankers involved in the pilot study.

Introduction

Agricultural production based on value of output from Australia is the most volatile in the world and the most volatile sector of the Australian economy (Keogh, 2013). This volatility conveys a level of risk that needs to be managed as an integral part of a farming business.

Historically most farmers have developed long term strategies and operational tactics to cope with this volatility. While some may argue this could be improved, the ability of most farmers to remain on the land in spite of this volatility means they have been able to balance cash flow requirements, annual profit and long term equity issues. Diversification in crop type, enterprise mix and property location are three common strategies used to manage production and income volatility.

Given the inherent risk in farming, it would be fair to expect agricultural extension would be well versed in supporting farmers making risky decisions. However this is not the case (with the possible exception of grain marketing). The skills most farmers have developed in managing risk and uncertainty is based on intuition and experience rather than on useful extension materials and knowledgeable advisory support.

Why is this the case? I suggest there are three main reasons:

1. Most extension practitioners don't fully understand the meaning of risk.

2. The extension materials extension practitioners prepare use averages and rarely show the extremes (where critical risk lies).

3. Risk involves choice so is inextricably linked with decision making.

Understanding risk

When we talk about risk most of us immediately think about the negative consequences if an action goes bad. This thinking is reinforced by definitions of risk included within dictionaries. However this is only one aspect of risk. The word risk is derived from the Italian word risicare, which means 'to dare'. To manage risk effectively we need to understand both the downside or in other words, the potential harm from taking a risk but also the opportunities that taking a risk can offer.

There is no reward without risk. In farming risk is a necessary part of making returns. Managing risk is about making decisions that trade some level of acceptable risk for some level of acceptable return. Decisions can be made to reduce risk, but it usually comes at a price, namely lower returns.

A common definition of risk is likelihood by consequence. In other words risk requires knowing how often an event happens (the frequency) and what is the impact (the value) when it does happen. A decision that increases risk will either increase the likelihood of an event happening and/or increase the consequence if it does occur. This increased consequence may be a greater return, not just a greater loss.

We must remember everyone has a different position on risk. Financial security, stage of life, health, family circumstances, business and personal goals can influence the amount of risk an individual is willing to take on. This position can change rapidly, sometime triggered by sudden events. Importantly no position is right or wrong, it is what the individual is comfortable living with.

This creates a challenge for extension practitioners. To engage in meaningful discussion about risk with a client you need to know what level of risk they are comfortable with and constantly check this to know if it remains aligned with their circumstances and goals.

Extension materials focussed on averages

Average values are commonly used in agricultural extension. We talk about average yields, average prices and average costs. While these averages convey a value, they rarely have the frequency of this average occurring. This would be fine if we consistently got these average values, but in agriculture we rarely do. The key drivers of profit in agriculture, namely yield, prices and some costs have a range of values within and between production periods. If we use averages for analysis, it usually over estimates the profits and hides the volatility in those profits.

To illustrate this point the average 15 year historic APW pool wheat price is $299/t, inflated to 2011 dollars. The frequency the price has been between $294/t to $304/t (+/- $5/t of the average) is only 4.4%. This suggests we rarely get the average price for APW wheat.

Sensitivity analysis is often used to test values higher and lower than the average. Using the same APW pool wheat prices as before, we could increase or decrease this value by 20%. However the frequency the price is 20% below the average occurs more often that the price being 20% above the average. The reason for the difference is that the range of values is not normally distributed around the average, it is skewed.

Managing risk is not about the middle or the average, it is the opposite. It is appreciating what happens at the extremes, the size or value of these extremes and how often they occur.

In gambling, describing a particular result along with determining the likelihood of that result occurring is called framing the odds. It is important to realise that framing odds relies on opinion about the chance of a particular result in the future. When an opinion of one result is compared with opinions on other possible results, then we have framed the odds. With those framed odds, the farmer can make a more informed decision.

The degree of confidence in being able to predict a particular result can be quite variable depending on what we know. Keeping with the gambling theme, historic information about a horse or a dog is provided in a form guide. The guide is presented in a way than enables all the key pieces of information you need to know, both the results but also the circumstances in which they occurred. Both good and bad results are presented. For horse races it tells the number of starts, number of wins, number of places, how many times it has won in the dry, on a wet track, over what distances, etc. All this information is useful in comparing today to past results.

Recent advances in farming systems models such as MiDAS, APSIM and GrassGro enables historic climatic data to be combined with other possible conditions such as different soil and species types to calculate a range of other possible outcomes. These outcomes can then be statistically analysed to further help in framing the odds. In the Grain and Graze 2 program we have been examining historic prices and production (grain yields and pasture growth). Trial results are combined with modelling and statistical data fitting to create graphs which convey the range in value and the frequency these values occur. Rainfall has also been examined and modelled, providing farmers and advisers with new insights into the probabilities of certain rainfall patterns.

It must also be acknowledged that in some cases the information is limited, preventing any meaningful analysis. In these uncertain situations we just have to make a best guess and test the resilience of the business if a catastrophic set of circumstances did eventuate.

I believe there is enormous potential to improve the way we present information to farmers to enhance framing the odds. The Grains Research and Development Program (GRDC) are currently developing a series of form guides and will be evaluating these with farmers and advisers to determine if they help inform farm decision making.

Risk, choice and making a decision

As described previously the derivation of risk is 'to dare'. This implies there is opportunity but it also implies a choice. As individuals we can influence how much risk we expose ourselves to by making choices.

People make decisions all the time and because we constantly make them, we rarely consider how well equipped we are to make them. Extension practitioners, to be effective, need to understand how farmers make decisions and how proficient they are at making them. Three papers capture the essence of the issue; Kahneman and Tversky (1979), which describes the theory of how risk is incorporated in decision making, Gibb (2009) which identifies the 'rules' leading farmers in the dairy industry use to make good decisions and Long (2009) who explores a range of social factors that influence the decision making process. Appreciating the influence intuition, past experience and gut feel has on farming decisions is critical (Long, 2012). So is understanding the significance others have on shaping the final decision, be it other family members, trusted peers or advisers.

The capacity of farmers to make good decisions was highlighted in recent Grain and Graze 2 workshops on risk management conducted in Western Australia. These workshops uncovered a previously unrecognised demand by farmers to learn more about simple decision making processes (Danielle England, pers comm). Techniques like force field analysis, fishbone analysis (Carman and Keith, 1994) and approaches to make hard decisions easier (Newell, 2011) were highly sought to help build the capacity of farmers to manage risk and uncertainty.

Extension practitioners can do more to help farmers make good decisions. To be seen as a good decision, we need to increase the chances of achieving a favourable outcome for the farmer, one that improves options and provides pleasure or reward. A good decision is right for the farmer, their business, the family and their stage in life. Importantly it is an informed decision where the farmer appreciates the consequences and will have the least regret if it goes bad. Whether it is the ‘right’ decision is a matter of time. Good analysis combined with good discussion helps to make a good decision.

Analysing risk in the Grain and Graze program

The Grain and Graze 2 program in Southern Victoria has completed profit analysis on twenty mixed farms, with another twenty to finalise. The analysis requires the creation of a simple profit and loss type spreadsheet to calculate enterprise and whole farm profit. It includes depreciation and labour costs but excludes finance payments and tax. Distributions are created to replace average values which the farmer identifies as risky, in this case values that cannot be accurately predicted at the start of the production cycle. Commonly this relates to yields, prices and some cost such as supplementary feeding and the cost of replacement animals.

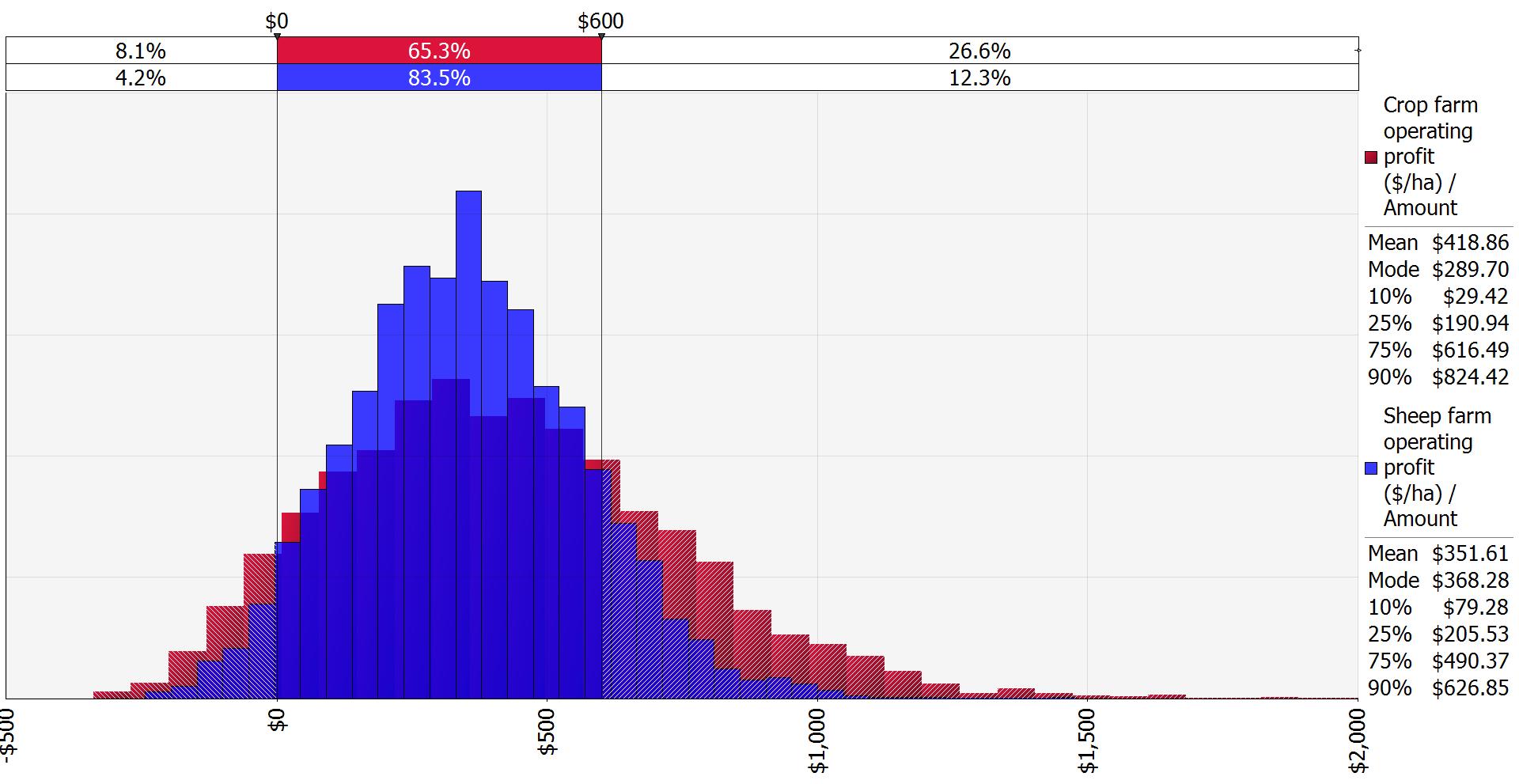

A program called @Risk (@Risk website) uses Monte Carlo simulations to create distributions of the range and frequency of certain profit results. These distributions convey risk because they represent value and frequency. Enterprises can be compared to examine the risk within each. A typical result is presented (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of enterprise profit for cropping and sheep ($/ha).

Figure 1 conveys common themes emerging from the analysis. The first is that the average or mean profit from cropping is $419/ha compared to $352/ha for the sheep operation, meaning cropping is more profitable than sheep in the long run. If we had used average values rather than distributions then this is the result we would have got. However the mode, which is the most frequent result that has occurred, is less than the mean for the cropping, indicating the spread is not evenly distributed around the middle. It is skewed to the left or lower values. In the case of the sheep operation it is approximately $16/ha higher, but for the cropping it is $129/ha less. Knowing the mode as well as the mean allows the farmer to appreciate how much higher or lower the most frequent profit is likely to occur.

Secondly the distribution for cropping is wider and flatter than the distribution for sheep. It has a greater range and is more volatile and means the downside risk or chances of making a loss are greater with cropping than livestock. However the upside risk or chances of making large profits is also greater with cropping compared to livestock. The cropping is more risky not only because it has potential for higher losses but because it also has potential for greater returns. In this example the chances of not making a profit are twice as high with cropping compared with sheep (8.1% or approximately one year in twelve with cropping compared to 4.2% or one year in twenty four with sheep). Conversely the upside risk of say making $600/ha from cropping is likely to occur one year in four with cropping compared to one year in eight with sheep.

Thirdly we can consider the probability of making different amounts of profit to meet financing cost and pay tax. In this case if we needed to make $75/ha/yr to meet these commitments, then the odds are we would not achieve this one year in seven with cropping but only one year in eleven with the sheep enterprise.

Additional analysis can be performed to understand what are the main risky variables causing the volatility and contributing to the extreme results. From this changes can be identified and tested.

Lessons from the Grain and Graze 2 analysis

The use of Monte Carlo simulations has been used in Australian agriculture before (Hutchings and Nordblom, 2011, Monjardino et al, 2012) and is considered best practice in examining risk (Malcolm, 2009). However, most analysis is on an example farm or farms with different enterprise mixes in a district. This means the analysis is unable to reflect the individuality farmers require to fully appreciate the risk in their business, and therefore, cannot be used to examine how well the outputs reconcile with their appetite for risk.

The focus of the Grain and Graze 2 work is to evaluate if completing farm profit analysis using Monte Carlo simulation for each unique farming business is useful in helping to make more informed decisions. The analysis involves collecting individual business data, creating and validating the risky distributions with the farmer and discussing the outputs. The need for a comprehensive understanding of the issues and challenges in farmer decision making has proven critical for the full benefits of this analysis to be realised.

Evaluation of all the farmers is yet to be completed, however a snapshot of some early interview responses suggest the analysis is making a valuable addition to the way farmers and the support sector consider risk. A snapshot of comments include:

- 'It put some numbers around my gut feel' - Established farmer who felt the cropping country they had leased had increased risk in their business.

- 'This adds a new dimension to the analysis we receive from farmers and is likely to influence our lending conditions' - Banker who sat in on analysis completed with one of their clients.

- 'It's fantastic, it gives a me a far better understanding of how my advice about changing enterprises will affect risk in their business' - Experienced farm adviser.

- 'If I'd known then what I know now I never would have gone this hard into cropping' - Young farmer who rapidly moved out of livestock because of the lure of bigger average returns from cropping.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Tom Jackson, Bill Malcolm and Bill Long who have shared their knowledge and wisdom and to the GRDC for their financial support in the Grain and Graze 2 program.

Reference list

Carman K Keith K (ed.) 1994, 'Community Consultation Techniques: Purposes, Processes and Pitfalls. A guide for planners and facilitators' Department of Primary Industries, Queensland.

Hutchings T Nordblom T 2011, 'A financial analysis of the effect of the mix of crop and sheep enterprises on the risk profile of dryland farms in South east Australia' in Proceedings of the fifty fifth annual convention of the Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics society, Melbourne, Australia.

Gibb I 2009, 'How do some farm managers always seem to make the right decision?' in Flanagan-Smith C (ed.), Making it practical, Discussion paper for Birchip Cropping Group. Birchip, Victoria.

Kahneman D Tversky A 1979, 'Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Making under Risk', Econometrica 47: 263-91.

Keogh M 2013, 'Global and commercial realities facing Australian grain growers' in Robust cropping systems - the next step. GRDC Grains Research Update for Advisors 2013. ORM Communications, Bendigo, Vic. pp 13-30.

Long W 2009, 'People Factors Driving Farm Decisions or A Bit of Bush Psychology' in Grains Research Update, Adelaide, Jon Lamb Communications, St Peters, South Australia

Long W 2012, 'The Logic behind Irrational Decisions', Grains Research Farm Business Update for Advisors - Adelaide. ORM Communications, Bendigo, Vic.

Malcolm W 2009, 'Imagining the Future with Rigour: Risk principles and practice in crop and animal production, paper presented to The Mackinnon Project Seminar: Risk Management – the role of livestock in farming systems, University of Melbourne.

Monjardino M, McBeath T, Brennan E and Llewellyn R 2012 'Revisiting N fertilisation rates in low-rainfall grain cropping regions of Australia: A risk' in Proceedings of the fifty sixth annual convention of the Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics society, Freemantle, Australia.

Newell B 2010, 'Risk, uncertainty and decision making: A physiological perspective' paper presented to the Grain and Graze 2 national seminar on risk and uncertainty Melbourne. RMCG Consulting Bendigo.

Contact details

Cam Nicholson,

Nicon Rural Services

nicon@pipeline.com.au

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK