Farming systems strategies to manage fleabane and feathertop Rhodes grass

Author: Richard Daniel, Northern Grower Alliance | Date: 31 Jul 2015

Take home messages

- Glyphosate resistant and tolerant weeds are a major threat to our reduced tillage cropping systems

- Although residual herbicides will limit re-cropping options and will not provide complete control, they are a key part of successful management

- Double-knock herbicide strategies (sequential application of two different weed control tactics) are useful tools but the herbicide choices and optimal timings will vary by weed species

- Incorporate other weed management tactics e.g. crop competition to assist herbicide control

- Cultivation may need to be considered as a salvage option to avoid seed bank replenishment

The issue

Weed management, particularly in reduced tillage fallows, has become an increasingly complex and expensive part of cropping in the northern grains region. Why? - Our heavy reliance on glyphosate has selected for species that were either naturally more glyphosate tolerant or selected for glyphosate resistant populations. Two of the key weeds that are causing major cropping headaches are flaxleaf fleabane (Conyza bonariensis) and feathertop Rhodes grass (Chloris virgata):

Flaxleaf fleabane

For nearly two decades, fleabane has been a major weed management issue in the northern cropping region, particularly in reduced tillage systems. Fleabane is a wind-borne, surface germinating weed that thrives in situations of low competition. Germination flushes typically occur in autumn and spring when surface soil moisture levels stay high for a few days. However emergence can occur at nearly all times of the year.

One of the key issues with fleabane is that knock-down control of large plants in the summer fallow gives variable results and is also very expensive.

Resistance levels

Glyphosate resistance has been confirmed in fleabane. There is a large amount of variability in the response of fleabane to glyphosate with many samples from non-cropping areas still well controlled by glyphosate whilst increased levels of resistance are found in fleabane from reduced tillage cropping situations. The most recent survey has focused on non-cropping situations with a large number of resistant populations found on roadsides and railway lines etc where glyphosate alone has been the principal weed management tool employed.

Non chemical strategies

a) Crop competition

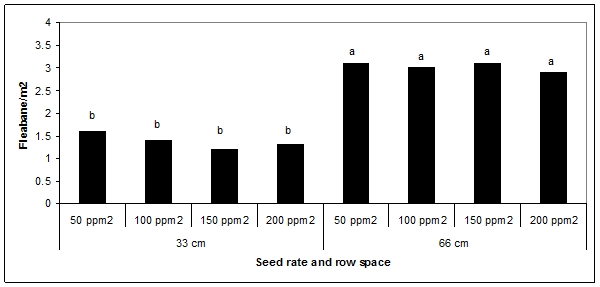

Although large fleabane can be extremely difficult and expensive to control in a summer fallow, seedling fleabane is generally poorly competitive. A valuable component of fleabane management is to utilise the benefits from crop competition to aid overall management e.g. substituting wheat with barley, sowing on narrower row spacings where possible and ensuring that planting rates are kept high. Frequently the ‘blow out’ scenarios for fleabane are where skip row or poorly competitive crops are grown without any effective fleabane herbicide management.

Figure 1. Effect of row spacing and plant population on fleabane population at Trangie in 2011 (NSW DPI)

b) Cultivation

Fleabane is a weed that proliferates in no-till farming systems. Part of the reason is that many populations of fleabane have a level of resistance to glyphosate but it is also due to the ecology of the weed. Fleabane requires light and a temperature of between 10-25°C (optimal 20°C) for germination and will only emerge from the top 1 cm of soil. No seedlings emerge from a depth of 2 cm or below (Widderick, 2009).

Cultivation to bury seed to a depth deeper than 1 cm can be an effective tool to manage fleabane populations. Although this approach can dramatically reduce fleabane emergence numbers, it also increases the longevity of the seed i.e. seed that is buried will not germinate but it will remain viable for a longer period. An occasional cultivation can be a useful tool for seed bank management but this is not a technique to utilise frequently as it will simply return viable seeds to the soil surface.

Cultivation may also be a viable option for salvage management. Where ‘blow outs’ occur this may be the only economic option to effectively control large flowering plants.

c) Monitoring

Monitoring is a key part of any weed management but is particularly important for fleabane. Fleabane can survive at small growth stages under a competitive crop and be easily overlooked. However once the crop is removed, the weed develops very quickly and the opportunity for effective control can be missed if monitoring isn’t conducted.

Herbicide strategies

Fleabane management improved dramatically when we stopped targeting large plants in the summer fallow as the primary management timing and started to focus management on the winter crop phase. There are three key stages where herbicides can be useful to manage fleabane populations; pre plant, in-crop and post-harvest.

a) Residual herbicides (fallow and in-crop)

One of the most effective strategies to manage fleabane is the use of residual herbicides in fallow or in-crop. Trials have consistently shown good levels of efficacy from a range of residual herbicides commonly used in sorghum, cotton, chickpeas and winter cereals.

There are at least three registrations for residual fleabane management in fallow:

Residual control only:

Balance® (750g/kg isoxaflutole) at 100 g/ha

Terbyne® Xtreme (875 g/kg terbuthylazine) at 0.86-1.2 kg/ha

Residual (and knockdown) in fallow:

FallowBoss® Tordon® (300g/L 2,4 D + 75g/L picloram + 7.5g/L aminopyralid)

- at 700mL/ha + Ripper® (480g/L glyphosate) at 1.5-2.25L/ha +/- a double knock of Spray.Seed® (135g/L paraquat + 115g/L diquat) at 1.6L/ha, at least 4 months prior to planting sorghum or winter cereals

- at 700 mL/ha + atrazine (600 g ai/L) at 3-5 L/ha, at least 4 months prior to planting sorghum

Tordon® 75 D (300g/L 2,4 D + 75g/L picloram) at 0.7 L/ha + glyphosate

Additional product registrations for in-crop knockdown and residual herbicide use, particularly in winter cereals, are still being sought. There are a range of commonly used winter cereal herbicides with useful knockdown and residual fleabane activity. Trial work to date has indicated that increasing water volumes from 50-100 L/ha may help the consistency of residual control with application timing to ensure good herbicide/ soil contact also important.

b) Knockdown herbicides (fallow and in-crop)

Group I herbicides have been the key products for fallow management of fleabane with 2,4 D amine and picloram/2,4-D products the most consistent herbicides evaluated. Despite glyphosate alone generally giving poor control of fleabane, trial work has consistently shown a benefit from tank mixing glyphosate with 2,4-D and picloram/2,4-D products in the first application. Registrations for knockdown management in fallow or crop include:

Knockdown in fallow:

- Amicide® Advance (700g/L 2,4-D) at 0.65-1.1 L/ha + Weedmaster DST (470g/L glyphosate) at a min of 1.4 L/ha. Follow with a doubleknock of Nuquat® (250g/L paraquat) at 1.6 -2.0 L/ha when weeds are from stem elongation to flowering.

- FallowBoss Tordon at 700 mL/ha + Ripper® at 1.5-2.25 L/ha (can also be followed with Spray®Seed at 1.6 L/ha as a double-knock) – prior to winter cereals or sorghum

- Tordon® 75 D (2,4 D + picloram) at 0.7 L/ha + glyphosate

- Sharpen® (700g/kg saflufenacil) at 17-34 g/ha + Hasten® spray oil +/- glyphosate

Knockdown in winter cereals:

- Amicide Advance at 1.5L/ha

- FallowBoss Tordon at 300 mL/ha

- Hotshot® (10g/L aminopyralid + 140g/L fluroxypyr) at 750 mL/ha + either metsulfuron 5 g/ha (600 g ai/kg) or MCPA LVE 580 mL/ha (600 g ai/L) (refer to label for appropriate growth stages)

- Lontrel® Advanced (600g/l clopyralid) at 150mL/ha

- Paradigm® (200g/kg halauxifen Group I + 200g/kg florasulam Group B) at 25 g/ha + MCPA LVE at 300-600 mL/ha (600 g ai/L)

c) Double-knock control

The most consistent and effective double-knock control of fleabane has involved including 2,4 D or picloram/2,4-D products + glyphosate in the first application followed by paraquat as the second. Glyphosate alone followed by paraquat will result in high levels of leaf desiccation but plants will generally recover.

Timing of the second application in fleabane is aimed at ~7-14 days after the first application. However the interval to the second knock appears quite flexible. Increased efficacy is obtained when fleabane is actively growing or if rosette stages can be targeted. Although complete control can be obtained in some situations e.g. summer 2012/13, control levels frequently only reached ~70-80%, particularly when targeting large flowering fleabane under moisture stressed conditions. The high cost of fallow double-knock approaches, and inconsistency in actual control level of large mature plants, is a key reason that proactive fleabane management should be focussed at other growth stages.

Key points fleabane

- Thrives in situations of low competition; avoid wide row cropping unless effective residual herbicides are included

- Tillage can have a role for both seed burial and for salvage management, but will not be effective for seed burial if used too frequently

- Successful growers have increased their focus on fleabane management in winter (crop or fallow) to avoid expensive and variable salvage control in the summer

- Utilise residual chemistry wherever possible and aim to control ‘escapes’ with camera spray technology

- 2,4 D or picloram/2,4-D is a critical tool for consistent double-knock control

Feathertop Rhodes grass (FTR)

FTR has emerged as an important weed management issue in southern Qld and northern NSW since ~2008. It is another small seeded weed species that germinates on, or close to, the soil surface. It has rapid early growth rates and can become moisture stressed quickly. FTR prefers situations of low competition for establishment but similar to fleabane is a tough competitor once well established. FTR generally will germinate more quickly and on smaller rain events than many other weed species and is often seen as an ‘early coloniser’. Although FTR is well established in central Qld, it is still more frequently an ‘emerging’ threat further south.

Two FTR characteristics that can be useful to assist control are that seed viability does not appear to be improved by seed burial (common for a lot of other weeds) and the seed longevity is short (~12 months). This means if effective control strategies can be used for a period of ~12-18 months, FTR problem paddocks can often be quickly returned to full production.

Tolerance to glyphosate

Weed scientists do not consider FTR to be resistant to glyphosate as there has never been an actual label claim for this weed. However it is clear that many populations are tolerant of glyphosate ie will not be controlled by glyphosate. From a management viewpoint, the result is the same; fallow management relying on glyphosate as the primary herbicide will select for FTR (or fleabane) populations.

Non chemical strategies

a) Crop rotation

In SQ and Nthn NSW, FTR is predominantly a spring to autumn management problem. Strategies of increased crop competition in winter have not yet been shown to be important management tools but crop rotation is certainly important. Sorghum is frequently seen as ‘blow out’ crop, despite useful but relatively short lived residual herbicide options. The issue in sorghum is that there is little or no opportunity for a selective herbicide to be used to control late in-crop germinations of FTR. This becomes an ideal scenario for FTR build-up particularly when combined with the wide or skip row configurations. Crops such as mungbeans and sunflowers are better options for FTR management as they allow a combination of residual herbicides and also in-crop post emergence control measures. Mungbeans may also provide a benefit by providing rapid row closure and increased levels of competition.

Winter crop options such as wheat and chickpeas also allow the use of in-crop herbicides that can assist with summer grass weed control.

b) Cultivation

Cultivation to bury seed is an effective strategy for managing FTR seed banks but will need to be combined with other management strategies for full control e.g. use of residual herbicides.

Cultivation may also be a viable option for salvage management. Where ‘blow outs’ occur this may be an economic option to effectively control large flowering plants.

c) Burning

Trial work conducted by DAF has shown promise from the use of burning, for the control of mature FTR plants. However, for the plants to be dry enough to carry a fire, they will have already returned vast quantities of seed to the soil. Burning removes the bulk of vegetative material (and enables residual herbicides to actually contact the ground) and can also be an effective tool for reducing the viable seed bank. This is certainly not a primary strategy for FTR management but may be an option in ‘blow out’ scenarios.

d) Patch management

Although FTR can be wind dispersed, it is frequently found in reasonably defined patches compared to weeds such as common sowthistle. This habit allows for a range of techniques to be employed on a patch management scale if monitoring is effective e.g. for small patches or new incursions, chipping, pulling, spot spraying or even cultivation can be employed and for mature plants burning may be employed followed by strategic cultivation and or the use of residual herbicides. Time spent trying to eliminate FTR at this stage can prevent a lot of long term management issues.

Herbicide strategies

a) Residual herbicides (fallow and in-crop)

FTR is generally poorly controlled by glyphosate alone, even when sprayed under favourable conditions at the seedling stage. Trial work has shown that residual herbicides generally provide the most effective control, a similar pattern to that seen with fleabane. A wide range of currently registered residual herbicides are being screened and offer promise in both fallow and in-crop situations. The only product currently registered for FTR control is Balance at 100 g/ha for fallow use.

b) Knockdown herbicides (in-crop)

Currently the only registrations for knockdown of FTR are from the use of Group A herbicides (butroxydim, clethodim) in cotton, mungbeans and other broadleaf summer crops.

c) Double-knock control

A glyphosate followed by paraquat double-knock is a very effective strategy on barnyard grass, however the same approach is variable and generally disappointing for FTR management. Research has shown that a small number of Group A herbicides (in particular the ‘fop’ class) can be effective against FTR (although none currently registered). Permit applications need to be managed within a number of constraints.

- Although they can provide high levels of efficacy on fresh and seedling FTR, they need to be followed by a paraquat double-knock to get consistent high levels of final control

- Group A herbicides have a high risk for resistance selection, again requiring follow up with paraquat

- Many Group A herbicides have plantback restrictions to cereal crops

- Group A herbicides generally have narrower windows of weed growth stage for successful use than herbicides such as glyphosate ie Group A herbicides will generally give unsatisfactory results on flowering and/or moisture stressed FTR

- Not all Group A herbicides are effective on FTR

A permit (PER12941) has been issued, in Qld only (Expires 31 Aug 2016), for the control of 3-leaf to early tiller FTR in summer fallow situations prior to planting mungbeans. It is for 520g/L haloxyfop at 150 -300 mL/ha followed by paraquat at a minimum of 1.6 L/ha, within 7-14 days after the first application.

Timing of the second application for FTR is still being refined but application at ~7-14 days generally provides the most consistent control. Application of paraquat at shorter intervals can be successful, when the Group A herbicide is translocated rapidly through the plant, but has resulted in more variable control in field trials.

Key points Feathertop Rhodes grass (FTR)

- Treat patches aggressively, even with cultivation or burning, to avoid paddock blow outs

- Glyphosate alone or glyphosate followed by paraquat is generally poor

- Utilise residual chemistry wherever possible and aim to control ‘escapes’ with camera spray technology

- A double-knock of Verdict® followed by paraquat can be used in Qld under permit prior to planting mungbeans where large spring flushes of FTR occur

Conclusions

There are a number of common threads in the management of both fleabane and FTR.

- They are difficult and expensive to control in summer fallow, with variable results often obtained

- However both are sensitive to a wide range of registered residual herbicides

- Both weeds establish rapidly in min till systems particularly in low crop competition scenarios

- Neither weed establishes well when the seed is buried to 2 cm or deeper

- Neither weed can be successfully controlled by a single strategy

- A planned combination of herbicide and non-herbicide strategies is needed for effective management

- Double knock herbicide strategies are very useful but only a component of the overall package

- Seed persistence is relatively short, so an aggressive approach of 100% control for ~2 seasons can rapidly deplete the seedbank.

Acknowledgments

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support.

Thank you to Michael Widderick (DAF) and Rohan Brill (NSW DPI) for their input and provision of trial data.

Contact details

Richard Daniel

Northern Grower Alliance

Ph: 07 4639 5344

Email: richard.daniel@nga.org.au

® Registered trademark

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK