Making good decisions great

Author: Cam Nicholson, Nicon Rural Services, Geelong | Date: 25 Feb 2015

Take home message

Don’t assume people know how to make a good decision.

A ‘good’ decision is an informed decision where you need to appreciate the consequences of the various actions, especially the potential losses.

Seek to understand what may be subconscious influences on a decision, be it the type of decision required, the ‘rules’ being applied, stress, emotion, the growers values and personality.

Advisors can develop the capacity to apply the right process to enhance decision making but also to better ‘read’ and help the clients they are working with.

We make decisions all the time so what’s there to learn?

Well a lot. In fact there is a lot to understand about your clients as well as the decision making processes they use.

Have you ever been in a situation with a client where your advice, that seems so logical and obvious, isn’t followed? The numbers stack up, the science supports it, the case is well presented and you know it will benefit their bottom line. Yet it never seems to get implemented or if it does the timing is wrong or a few parts of the recipe are left out.

We, as advisors and consultants often make the mistake of believing farm management decisions are largely influenced by technical or intellectual information. We present the argument in a way that we think makes sense, using facts and analysis that ‘speaks for itself’. Sadly these facts and figures don’t.

In this paper I wish to challenge you about the decision making process you (or your clients) use and how we might improve it to become more effective.

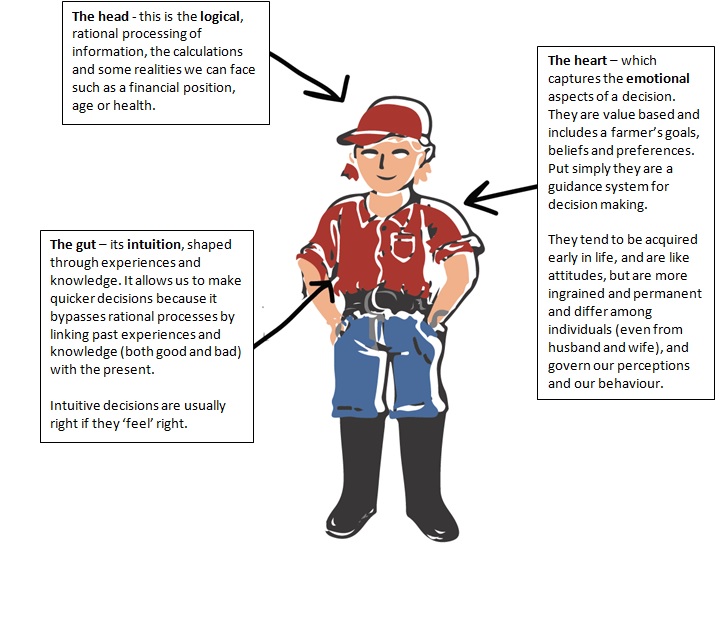

The head, the heart and the gut

Firstly we need to understand there are three broad influences that shape a decision. These are simply described as the head, the heart and the gut (figure 1).

Image courtesy of Alice long, AgCommunicators

Figure 1. The head, heart and gut influence our decisions.

The relative influence of the head, the heart and the gut depends on;

- The type of decision required (simple, complicated, complex)

- The relevant information available (usually imperfect)

- The risk involved

- The personality of the decision maker.

The type of decision required

Not all decisions are the same. Some are simple because there are few issues to deal with, there is a logical approach to solve it and the information is at hand. For example knowing how much to herbicide to achieve knockdown of annual ryegrass is relatively straight forward as the label provides recommended rates and other critical comments.

A decision can become more complicated if we have issues with herbicide resistance, plant back periods, multiple species that require mixes of herbicides etc. Complicated decisions have more issues to deal with but generally there is right answer that can be worked through until a satisfactory solution is found.

The third type of decisions are complex. These are decisions that have many issues, commonly with other members of the farming business. The possible solutions are not easy to compare and there can be many ‘right’ answers and possible pathways to get to an informed decision.

The value in knowing what decision you are dealing with is that it changes the approach you should take. Generally as decisions become more complex, the heart and the gut have an ever increasing influence on the decision. But not always - why else would we buy the new green tractor when we really don’t need it?

The information available - intuition and rules of thumb

We cannot expect to know everything. Two factors help us make timely decisions with imperfect knowledge. These are intuition and rules of thumb.

Intuition is formed primarily through experience. It allows us to make quicker decisions because it bypasses rational processes and relies on past experiences and knowledge (both good and bad) to inform what should be done in the future. Intuition builds over time, with the more experiences and greater knowledge you have, the larger your intuitive capacity. The ‘quality’ of past experience and knowledge determines the ‘value’ of your intuition.

Rules of thumb are mental shortcuts that we use to simplify and speed up decision making. They are similar to intuition in that they can be useful in bridging gaps in knowledge, allowing decisions to be made without extensive analysis. The main difference between intuition and rules of thumb is their tangibility – rules of thumb are more easily learnt, taught and transferred whereas intuition is not.

Rules of thumb are often used unconsciously, they are the thoughts that immediately comes to mind. It is the starting point for a decision. Decisions guided by rules of thumb may be as basic as ‘how many spoons of tea should I put in the pot?’ through to ‘how much of my expected yield should I forward sell?’

All advisors will have their rules of thumb. In a recent series of workshops across southern Australia farmers, consultants and researchers were asked to identify some of their rules of thumb. See if you recognise any of these?

- Cover wheat seed with soil to the depth of a matchbox on its side

- Only sow after weed seed has germinated

- Sell 1/3 grain at sowing, 1/3 later in the season and 1/3 at harvest

- $300/t is a good price for wheat (which may be different to the previous rule)

- Storing fallow rainfall buffers grain income in seasons with poor growing season rainfall

- If you can’t pay off new machinery in 3 or 4 seasons, then you can’t afford it

- If you can see your mother-in-law’s underwear on her clothesline, your houses are too close!

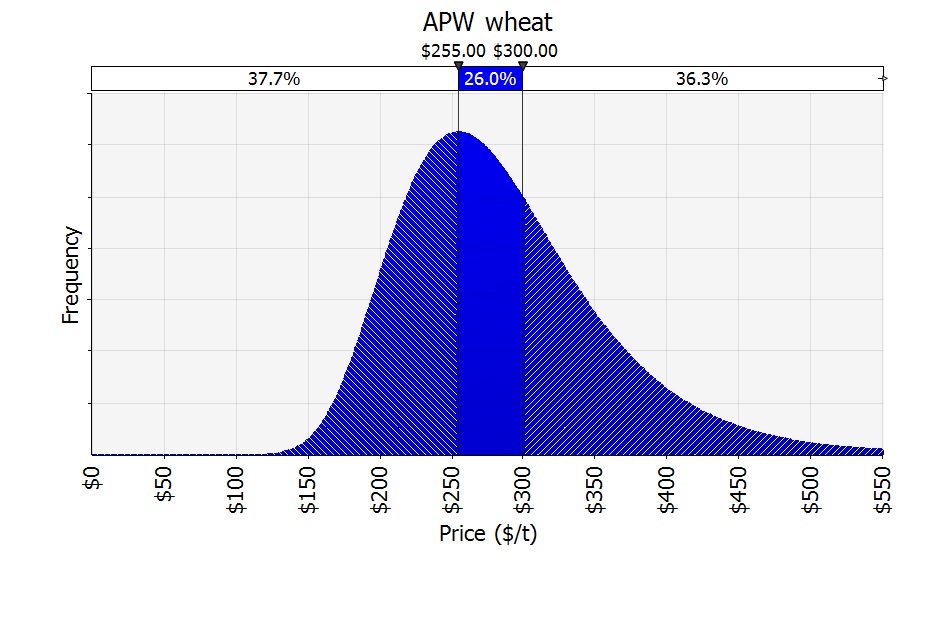

Good decisions are made based on good information, so it is important that rules of thumb have a solid foundation. A potential trap with rules of thumb (and sometimes intuition) is that we continue to rely on them when circumstances have changed or are different. They can also be sticking points for change and result in missed opportunities or unrealistic expectations. For example is $300/t a good price for wheat?

Historic information (July2003 to June 2014) for APW wheat in an Australian Port would suggest $300/t is above the average price of $287/t ($300/t is about a decile 6 price). However the most common price reached in this period of analysis is only $255/t, because the price distribution is uneven around the average (figure 2). If growers had $255/t in mind (because it is the price encountered most frequently), then $300/t is a substantial increase ($45/t) and may seem a good price, but compared to the average the difference is much less ($13/t).

Figure 2. price distribution for APW wheat at Geelong (July 2003 – June 2014)

To challenge the $300/t rule further, there may be times when the rule should not be strictly adhered to. In some cases, cash flow may be more important and a price of less than $300 can still be a profitable decision. Mae Connelly, a W.A. grain marketer with Farmanco stated in a workshop that “a good price is simply one that is profitable for your business”. It is important to know what makes a price profitable, and to be able to accurately make this decision, your must know your break-even price.

So the $300/t target is generally a good guide, but the importance of doing your own cost calculations and setting the margin you wish to achieve should not be overlooked.

Assumptions that underpin our rules of thumb can become so ingrained that we fail to consciously test their validity which leads to poorer decisions. They can even develop into beliefs and accepted as truths, and when challenged, people can become uncomfortable or defensive.

There is a simple technique to ‘unpack’ a rule of thumb (ROT) to check its validity. Ask yourself these five questions;

- Origin: where do you remember first hearing the ROT?

- Experience: what has been your experience with the rule? Have you found it to be (un)reliable?

- Research: what research verifies the rule?

- Blind spots: what areas may the rule may cause you to neglect?

- Adaptive management: how have you used this rule in different ways in your management?

The risk involved

Farming is a risky business, with significant volatility in prices, yields and some costs. We accept this as a necessary part of farming and a necessary part of making a return.

Farmers have become very good at managing risk, employing strategies such as diversification of crop type and enterprise mix, operating with a low cost structure and creating off farm assets and reserves. Much of this learning has been from experience, the school of hard knocks and expresses itself through their intuition (gut).

Risk is an individual thing, what is acceptable risk to one person may be unacceptable to another. It also changes over time due to things like stage in life, health, family circumstances and financial position.

This intuitive but changing ‘risk filter’ has a significant influence on what decisions are made. While the numbers or argument might be compelling to us, the unease a farmer may feel could be because it does not meet the risk they are willing to accept.

So if this risk filter is important in decision making, how well do we know our clients preference to risk? There are some simple tests described in the soon to be released Farm decision making - The interaction of personality, risk and economic analysis to make more informed decisions booklet produced through the Grain and Graze program that can be used to better understand your client’s position on risk.

The definition of risk is likelihood x consequence. To think of it another way, risk is how frequently an event occurs and what the value is when it does occur. It is derived from the Italian word risicare, which means to dare. There is little risk in making a decision where the outcome is predictable and it happens often. Risk lies in the extremes, both negative where the outcome is unfavourable but also in the positive, where rare high value events occur eg 1 in 20 year season combined with high prices.

By implication averages do not convey risk, because they indicate the middle of the range in values. Yet they are probably the most common way advisors compare scenarios and provide information to help inform a decision. For example we use average yields and average prices to predict an income.

To highlight this point refer back to figure 2. The average price for APW wheat at port from 2003 to 2014 (inflated to 2014 dollars) was $287/t, yet this actual price (+/- $5) is rarely achieved (only 4% of the time). The most common price was $255/t. We could apply sensitivity analysis say by looking at prices +/- $40 from the average (i.e $247/t and $327/t). However the chances of getting $247/t or less is roughly 1 year in 3 compared to the chances of getting $327 at 1 year in 4.

According Ben Newell, a psychology with the University of NSW, one reason people perceive a decision as being ‘hard’ is because there is a serious potential loss if things go wrong. Unless we are prepared to calculate and discuss the potential losses before a decision is made, we are avoiding one of the three requirements to make a hard decision easier.

If we wish to talk about risk with our clients we need to frame the odds. Historic information can be a very useful guide in framing these odds. The Grain and Graze program has developed a simple web based tool to compared historic prices to help frame the odds.

People and personalities

Farming is more than a business. While profits drive business, life is not all about profit. Agriculture is an industry based around people, with farms traditionally being family affairs, commonly inter-generational and set in a context of a close community. As such the emotional and social connection tends to be strong, with decisions that protect or enhance the human aspects often over-riding technological advances that may be available.

And we are all different! Understanding the human factors in decision making will not only help us understand the reasons behind our own decisions, but also some of the decisions that are made by others that may contradict our own.

Beliefs, values and goals shape the heart response referred to in figure 1. Without delving into these aspects in this paper, it is critical for advisors to appreciate the beliefs, values and goals of the people they are advising. It is also important for the people in the farming business to know these as well!

Corporate businesses identify the values they want to underpin their business decisions and culture. Where this is working well you will see “people walk the talk” making their business decisions based on the clearly identified values. Farming businesses often don’t share their values, they remain assumed. This can create serious problems and lasting resentment.

We all have personal aspirations and dreams, the thing we would like to achieve or to do in our lifetime. These are our goals. Often these float around in grower’s heads and they are not articulated to other members of the farming family, business associates or financiers. Sometimes our beliefs will even stop us from admitting them to ourselves. The culture of many farming businesses has been one of not setting and sharing goals.

Emotion and the fear of loss

We are all emotional beings. Our memories are linked to emotion and so are our past experiences. The decisions we make are influenced by our emotions at the time. Given the same data, we will make different decisions when we are angry or stressed compared to when we are relaxed and calm.

Research has shown we often seek a logical explanation to justify why we have made a decision driven by emotion. That spur of the moment emotional decision is ‘backed up’ by a ‘good’ reason.

Negative emotions can be very powerful. Daniel Kahnemann a scholar from Princeton University refers to the pain of loss as being twice as great as the pleasure of an equivalent gain. This means we will go out of our way to avoid the loss because of the way it makes us feel. Refer back to the earlier comment about not appreciating the potential loss being a major reason that makes a decision ‘hard’. We fear loss and it is a very powerful emotion. Considering this premise, are past emotional losses holding a farming business back because of the fear of another loss?

There are some simple techniques than can be applied to surface the beliefs, values, goals and emotions that can have an influence on a farmer’s decision (refer to the booklet Farm decision making - The interaction of personality, risk and economic analysis to make more informed decisions – Grain and Graze 2015). Advisors are encouraged to become familiar with these techniques.

Stress

Stress is commonly encountered in farming. This can be during periods of heavy work load such as seeding, shearing, harvest, because of poor seasons, when under financial pressure or if encountering relationship challenges. Like risk, when we think of stress we commonly associate it as being bad. This is only part of the story. Some types of stress (like risk) can be good and lead to favourable outcomes because it sharpens your alertness and your performance.

The body produces the hormone Cortisol when we are stressed. In short bursts, called acute stress, it primes the brain for improved function. However if stress continues over a long period of time, called chronic stress, it will eventually impair the decision making process, sometimes to the point of inaction. When people are affected by chronic stress, the head part of decision making is reduced. What is diminished are reasoning, anticipation and the ability to plan and organise.

Denis Hoiberg from Lessons Learnt Consulting (GRDC Advisor Updates, 2013) provides some very useful insights into recognising and managing stress which won’t be repeated here. However the point is that long term stress has a lasting effect on the decisions a farmer will make, often leading to more conservative and risk adverse positions. After these periods it is rarely business as usual. A very insightful example of this is the report prepared by the Birchip Cropping Group called the Critical Breaking Point study (www.bcg.org.au/cb_pages/SocialResearchProjects)

Failure to recognise the impact emotion and stress has on a decisions usually leads to poorer decisions or decisions being made while in the “wrong frame of mind”. The outcomes can be profound, long lasting and lead to regret.

Personality

Our personality type influences the way we learn, make decisions, organise our lives and communicate with others. There is often debate about personality types, and the percentages, but roughly 40% of our personality is genetic, 40% is formed during our formative years (up to about the age of 14) and 20% is from socialisation.

It is important to recognise that while we have these innate personality preferences, it doesn’t mean we can’t learn to behave differently. By creating awareness of our preferences and how we automatically react, we can train ourselves to respond in a different way when it would be advantageous to do so, like making better decisions.

There are useful frameworks to help identify our personality type and temperament and that of our clients (eg Myers Briggs Type Indicator, Keirsey temperament testing etc). In using these frameworks, it is important to understand two things;

- There is no good or bad personality type, it’s about acknowledging the differences and recognizing how this can impact on our behaviour and decisions.

- Teams, families and businesses work well with a mix of personality types and can function extremely well when these differences are valued for what each can bring to the table.

While there is nothing black and white about personality types, there are four temperament groups that have distinct characteristics which helps describe differences in the farming population (taken from Strachan, 2011). The categories have been given their own names to align more with the characteristics of farming (table 1).

Three are some striking implications from the results;

- Approximately 80% of farmers want to work in the business not on the business

- Only 1 in 20 farmers are pre-disposed to be a team leader (and that team can be the family)

- Most farmers start at the detail and build to the vision and therefore often struggle to connect practical actions with long term goals

- Farmers often need to be ‘a jack of all trades’ but are usually only ‘masters of some’.

Making good decisions great

I believe there is significant scope for farmers and advisors to improve the decisions they make. This improvement will require some new thinking and possibly some new skills. Don’t assume people know how to make a good decision. Work to recognise what may be subconsciously influencing your clients decision, be it the type of decision required, the ‘rules’ being applied, stress, emotion, their values and personality.

Also reflect on yourself. Advisors can develop a capacity to not only apply the right process to improve the decision making, but to also read the signs. If you recognise a farmer has this type of personality, has theses values and has this position on risk, then you can better target the message or suggest ways to fill the possible deficiencies in their current decision making.

Table 1. Four broad temperament types and implications for farm roles and decisions

| Temperament type |

Short description |

Farmers |

Aust pop |

Suitable farm tasks |

Communication | Adoption of technology/practice |

| Dependables | Careful and reliable. They seek social stability, order, security and loyalty. They value the industry they are in and like the sense of belonging (I'm a farmer, I work in agriculture). Their skills include attention to detail, reliability, dependability and a capacity to work to a deadline. They are practically orientated and need to see results for their work. They like solid facts and dislike change for change sake. |

~ 55% |

~40% | Practical, hands on, will persevere with repetitive tasks |

They need to hear the task first and the instructions before explaining what it will lead to so there is purpose in the what they are doing |

Will adopt once the 'bugs are ironed out' and the technology or practice appears less risky |

| Doers | Doers value the here and now and get things done. They are at their best in a crisis, have a good sense of timing and don't mind taking risks. They will do whatever works for a quick and effective payoff even if they have to ignore convention and rules. They are good with detail, realistic, open minded and fairly tolerant but are impatient with theories and abstractions. Doers are often tempted to do it now and fix details later. |

~25% | ~15% | Practical, hands on, get pressure jobs done, crisis management |

Copy the pioneers if they can see tangible benefits. Will take a punt more so than the dependables. |

|

| Pioneers | Pioneers will try almost anything and will often be the first in the district to try something new. While they love getting their teeth into the start up, they have to concentrate to sustain interest once the project is past the design phase. Their strengths include problem solving, strategic planning and understanding complex systems. |

~15% | ~25 | Planning, seeking new ways and new innovation |

Need to see the big picture before accepting to do it |

They see opportunity and innovate. They don't need the recipe as they work it out as they go along. |

| Team builders |

Team builders are genuine people with integrity. They always trying to reach their goals without compromising their personal code of ethics. They tend to focus on the people needs of a business or community and make great community leaders. They support inclusive decision-making and firmly believe the strength of the business lies in the people. Their strengths include developing a vision and empowering others to join them. They often avoid conflict, strive for harmony and may ignore problems in the hope that they will go away. |

~5% | ~20% | People managers to ensure equity and harmony within the team. Often have a strong environment belief, to leave the land in a better condition for the next generation |

Any time as long as it makes lives easier and fits their values |

References

Strachan R (2011). Myers Briggs Type Indicator Preferences by Industry and Implications for Extension. In Shaping Change: Natural Resource Management, Agriculture and the Role of Extension. Australasia Pacific Extension Network. Eds: Jennings J, Packham R and Woodside D.

Acknowledgements

The thought behind this paper have been developed from some fabulous insights from many great advisors. The author would like to thank Jeanette Long, Danielle England, Zoe Creelman, Bill Long, Barry Mudge and David Cornish who made major contributions to the booklet Farm decision making - The interaction of personality, risk and economic analysis to make more informed decisions from which this paper is prepared

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through the support of the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support.

Contact details

Cam Nicholson

Nicon Rural Services

32 Stevens Street, Queenscliff Vic 3225

Ph: 03 5258 3860

Fx: 03 5258 1235

Email: cam@niconrural.com.au

GRDC Project Code: SFS023,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK