Farming systems managing profitability and risk in a grain business

Author: Ed Hunt (Ed Hunt Ag Consultancy) | Date: 16 Feb 2016

Introduction

The face of grain farming has changed dramatically over the last twenty years and the key factors influencing farm business profitability must be considered differently for businesses to be successful.

The number of individual farms has gone down, average cropped area per business has increased, there have been critical changes in the farm income to cost ratios and a shift from mixed farming systems to a much higher percentage of intensive cropping systems. Land values in grain growing areas have typically doubled; debt levels and total interest paid per grain farming business are at record levels and machinery costs per business have typically doubled. Climate variability in season and between seasons and trends over time has changed.

When combined this equals a new era for grain farming businesses. To be successful in this new era decisions must be made differently by farmers, and the advice, products and tools of the service providers are changing and must continue to change.

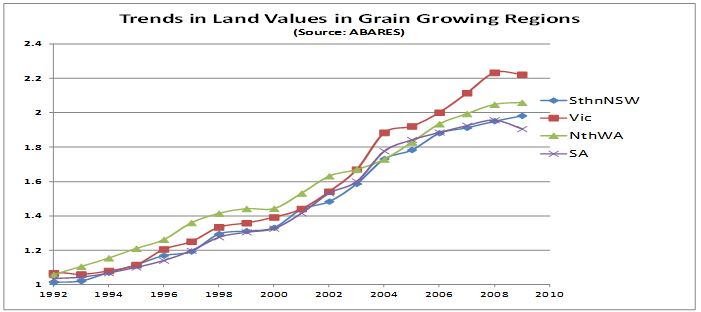

Figure 1 shows the trend in land values. Land values have doubled leading to larger balance sheets, but there is a growing disconnect between productive land value and what is being paid for the land; this is being contributed to by a dramatic decline in productivity growth. Coupled with an intensification of farming systems, a change in farm machinery costs and climate variability the farms of today have a very different risk profile to those of twenty years ago.

Figure 1: Trends in land values in grain growing regions.

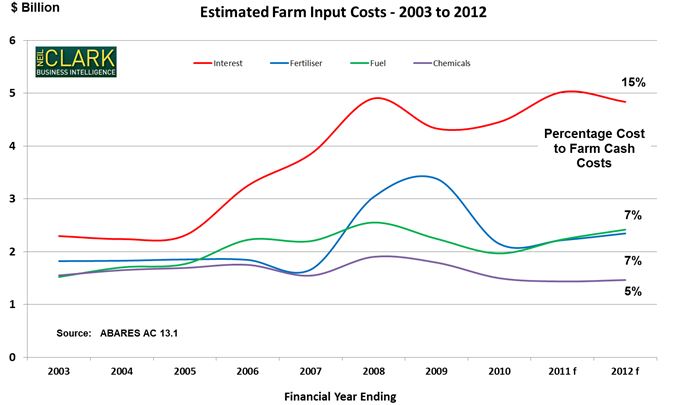

With the growth in land values, farms have larger balance sheets to leverage. As farms have increased in scale they typically use borrowings to do so. This has led to record levels of interest being paid per business as a percentage of their total farm costs. However, total bank lending is starting to decline as businesses recover from the millennium drought. We must remember that all this is occurring in an era of record low interest rates.

Figure 2: Estimated farm input costs 2003 -2012 (interest cost = 15%, fertiliser and fuel = 7% and chemicals = 5%).

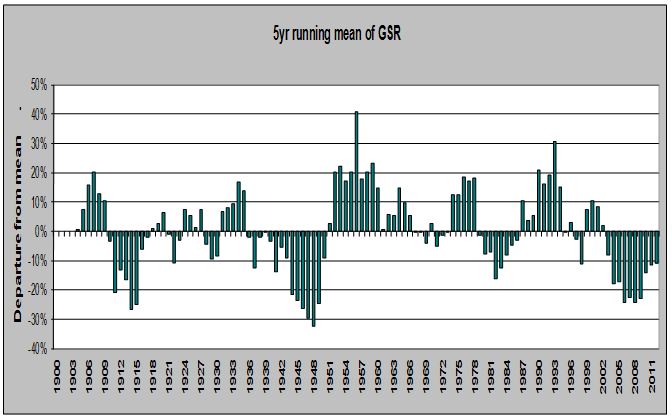

Seasonal ups and downs are not new to farming in Australia. Extended periods of low rainfall where the five year moving average of annual rainfall can be 20-30 per cent below the long term average have happened before and will probably happen again in the future (Figure 3). The challenge for Australian farmers is to develop resilient farm businesses that are able to cope with extended periods of below average rainfall.

Figure 3. Historic five year running mean for growing season rainfall (GSR) rainfall at West Wyalong.

Profit and risk workshops

Over the past two years we have worked with focus groups in South Australia, Victoria and New South Wales to evaluate the profitability and risk of farm businesses managing different faming systems in that environment. This work was undertaken in partnership with Mallee Sustainable Farming (MSF) through the Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC) funded Low Rainfall Profit and Risk project (DAS000119).

Five focus groups were located at West Wyalong, Cummins, Waikerie, Karoonda and Ouyen. Over two workshops, group participants developed a model farm that was representative of their local region. Some of the key characteristics that were described for each model farm included:

- Size, cropping intensity and enterprise mix

- Crop yields defined for seasonal deciles for three representative soil types

- Nitrogen fertiliser inputs by season and soil type

- Chemical inputs and other variable costs

- Freight costs

- Livestock enterprise

- Fixed costs

- Machinery ownership and re-investment strategies

- Family drawings, labour costs and off-farm income.

Using this information the cash flow and end cash balance for the model farm was calculated for a range of seasonal deciles (1, 3, 5, 7, 9.). This analysis was then repeated across multiple scenarios that were of interest to the workshop participants. Common scenarios included altering crop intensity, plus and minus livestock, business expansion and machinery investment.

Key messages from model farm analysis

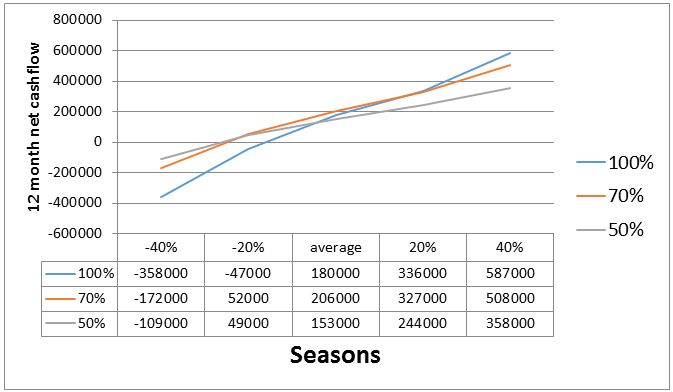

One of the most critical messages to come out of the project is that analysing business profitability in only an average season is almost a useless exercise. In most scenario’s analysis, the average (decile 5) season was a tipping point where both farms generally had a similar profitability. This is highlighted in Figure 4 which compares the West Wyalong model farm as a continuous cropping business (100% crop) to that of a mixed farming business with livestock at a 75 percent and 50 per cent crop intensity. In this example, the continuous cropping farm has a much greater capacity for profit in the better seasons. However, it could also be considered as a much riskier business than the mixed farm with greater losses in poor seasons. This detail could not have been established through a simple analysis of business profit in an average season.

Figure 4. Comparison of financial balance across seasonal deciles between a continuous cropping (100%) and mixed farm (75%) and (50%) scenarios at West Wyalong.

While each of the model farms were unique, there were many commonalities in the key messages arising from the analysis:

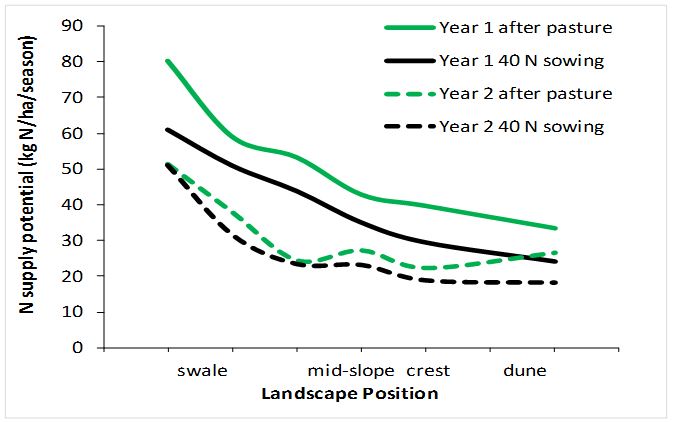

- It is difficult (both financially and practically) to maintain nitrogen inputs in long term continuous cropping farming systems. Profits in the high rainfall seasons are being constrained as farmers are unwilling to fertilise to the levels required to reach potential yields (Figure 5). More ‘natural’ nitrogen is required by the farming systems through more frequent legume phases in paddock rotations.

Figure 5: Different N supply at Karoonda.

- Farmers are relying on expensive chemical and fertiliser bills to maintain current high input farming systems which is in-turn increasing risk. Lower cereal intensities and a greater proportion of break crops and pastures in the rotation are required to reduce this risk.

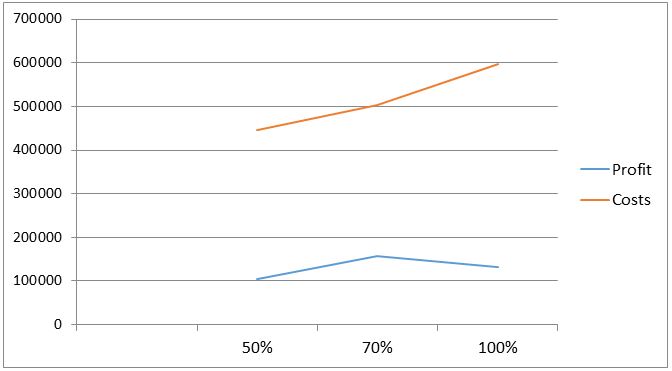

Figure 6 shows that profit is relatively flat at different cropping intensities at West Wyalong however the higher the cropping intensity the higher the costs.

Figure 6: Costs and profits at different cropping intensities West Wyalong.

- Livestock play an important role in moderating financial losses incurred from cropping in poor seasons. Businesses that choose to remove livestock need to find alternative methods to reduce risk. Examples include finding greater off-farm income or maintaining higher levels of equity.

- Maintaining investment in machinery is a large cost and increases risk considerably. Generally, greater critique of machinery investment decisions is required by considering carefully what type of machine is required to reliably complete the task required. Shifting a greater proportion of machinery investments into profitable seasons is another strategy to reduce financial exposure in poor seasons. The example in Table 1 is for the model farm at Waikerie which had the lowest rainfall of all the groups. By running the farm at 90 per cent equity and only purchasing machinery in average and above seasons the farm was close to breaking even in a Decile 3 year which is important for long term financial stability.

| Season | Net cash flow for 12 months |

|---|---|

| Decile 1 | -$160,000 |

| Decile 3 | -$11,000 |

| Decile 5 | $68,000 |

| Decile 7 | $128,000 |

| Decile 9 | $279,000 |

Conclusion

Long periods of below average rainfall are relatively common in Australia and should not be unexpected. The new era for grain farming businesses means businesses must be structured differently to be both profitable and resilient. While a current move to high input farming systems may provide for increased profitability in average to high rainfall years, more attention needs to be given to a business’s ability to cope with successive poor performing years. Planning and risk buffers must be extended out to cater for multiple years. Leveraging of increasing land values must be considered and managed carefully in an era of zero to negative productivity growth, increasing costs and record low interest rates, while still recognising that businesses must continue to increase in scale over time to remain competitive. In the low rainfall Mallee, lower cropping intensity, greater use of legume crops and pastures, livestock, off-farm income and prudent machinery expenditure are some of the key strategies businesses are using to remain profitable and to effectively manage risk. However, what the statistics and experience show is any farming system can be successful when managed well with the correct financial risk position for the business.

The future for Australian agriculture remains bright, and businesses who address the factors of the new era and plan for current trends will remain profitable and successful into the future.

Acknowledgement

Funding for this work was provided through the GRDC Project DAS000119 and their support gratefully acknowledged.

Contact details

Ed HuntEd Hunt Ag Consultancy

0428 289 028

edmund.hunt@bigpond.com

GRDC Project Code: DAS000119,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK