Markets for hay whats under the bonnet

Author: Colin Peace (JumbukAg Consulting) | Date: 11 Aug 2016

Background

During 2015 another poor growing season in many cropping areas of Victoria has given grain growers the opportunity to salvage some value from their crops by cutting them for hay. As the marketing of hay is dramatically different to grain and there are new risks involved, many growers have been reluctant to cut their crops for hay.

So that growers can approach this decision making process with more knowledge, this paper aims to provide some background to what can be an opaque topic, the hay market. Domestic dairy and export hay markets are discussed in terms of their current and future price drivers for hay.

Discussion

Most hay growers say that hay is often their most profitable cropping enterprise. While the production aspects are very similar to grain, cereal and vetch hay growers do require a working knowledge of livestock industries and their quality requirements.

The mechanics of the hay market

Due to its dense population of sheep and beef and dairy cattle, Victoria typically grows over 40 per cent of Australia’s fodder, but fodder in the form of hay and silage represents only a small portion of the total roughage needs for livestock.

Pastures provide the bulk of feed for ruminants and fodder is only a smaller supplementary feed. When droughts hit a broad range of grazing regions in Victoria, the demand for hay can spike dramatically. The volatility of hay prices is also enhanced by how tightly growers retain their hay for on-farm use. Unlike grain, only around 40 per cent of hay produced is typically sold each year.

Livestock and cropping industries of the irrigated regions of northern Victoria rely on affordable irrigation water to produce fodder through either extending the growing season and/or to irrigate highly productive summer crops.

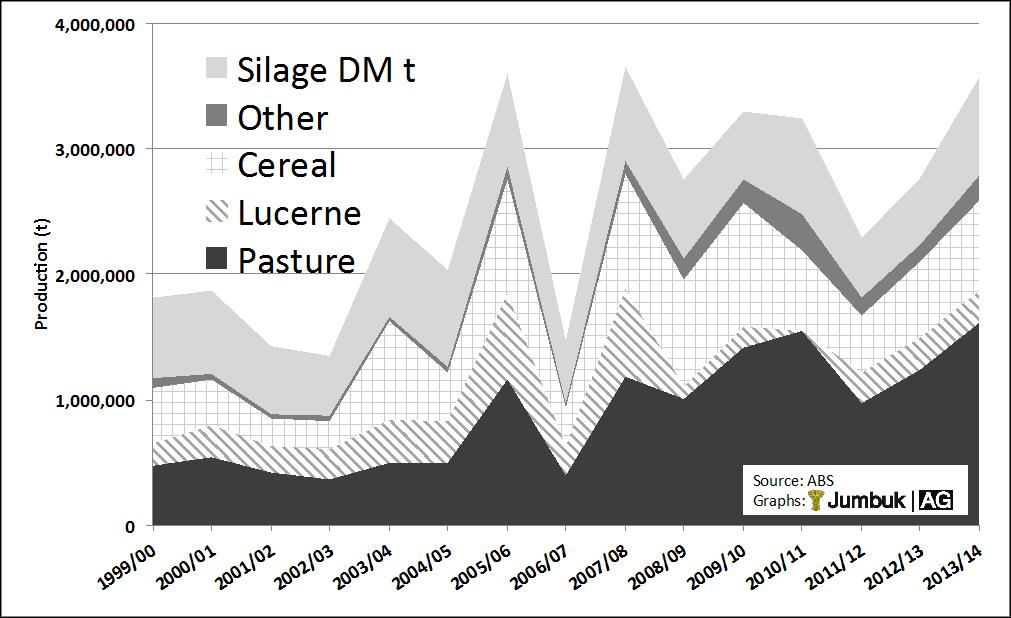

As shown in Figure 1, pasture hay is the largest hay type produced.

Figure 1: Victorian fodder production by type.

What happened in 2015?

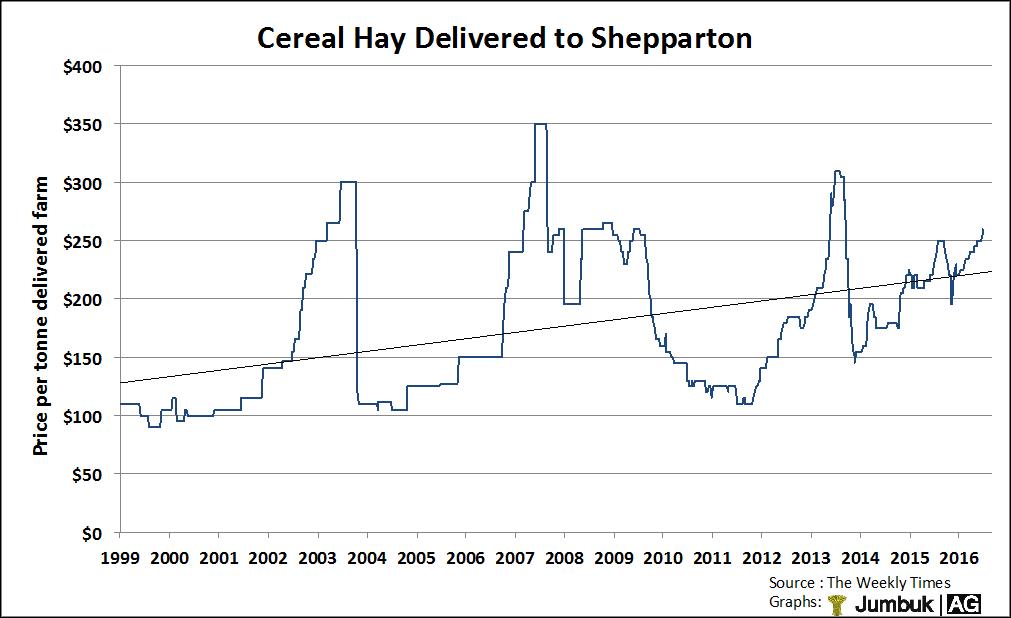

The April to November 2015 growing season rainfall was low but we have had worse. 2006/07 saw historically high hay prices when decile 1 rainfall or less fell during the 2006 growing season throughout south-eastern Australia. Unfortunately for the irrigated dairy farms of Northern Victoria this coincided with a collapse of water entitlements and an increase in the price of temporary irrigation water.

The hay market in winter of 2016 is $60 a tonne higher below winter of 2013 but still $40 above the long-term drought inspired trend line price. The hay price has increased due to the relatively drier weather in the south in 2015.

This drier weather saw very little silage cut in southwest Victoria and greatly reduced areas and yields for pasture hay in all areas. Some conservative estimates have reduced the Victorian area and yield of pasture hay, silage and other hay by 20 per cent. They estimate Victorian hay production at 2,150,000t or 850,000t lower than average. Some conservative estimates based on 15 per cent of the cereal crops being cut for hay in the Wimmera, Mallee and Loddon regions put an estimate of the additional cereal hay produced in 2015 at 630,000t.

With the depleted hay stocks that remain on farm and the buyers that are still to buy their winter hay needs, it appears that hay prices will remain high but nothing like 2007.

Figure 2: Victorian hay prices.

Hay buyers and quality

If livestock producers buy hay in proportion to their animal’s total intake, dairy farmers buy the most hay, followed by sheep farmers and beef producers.

Roughage such as hay is essential for ruminants and there are few substitutes when supplies are limiting. If hay prices exceed $300 a tonne some farmers turn to almond hulls but this is a reluctant choice for most.

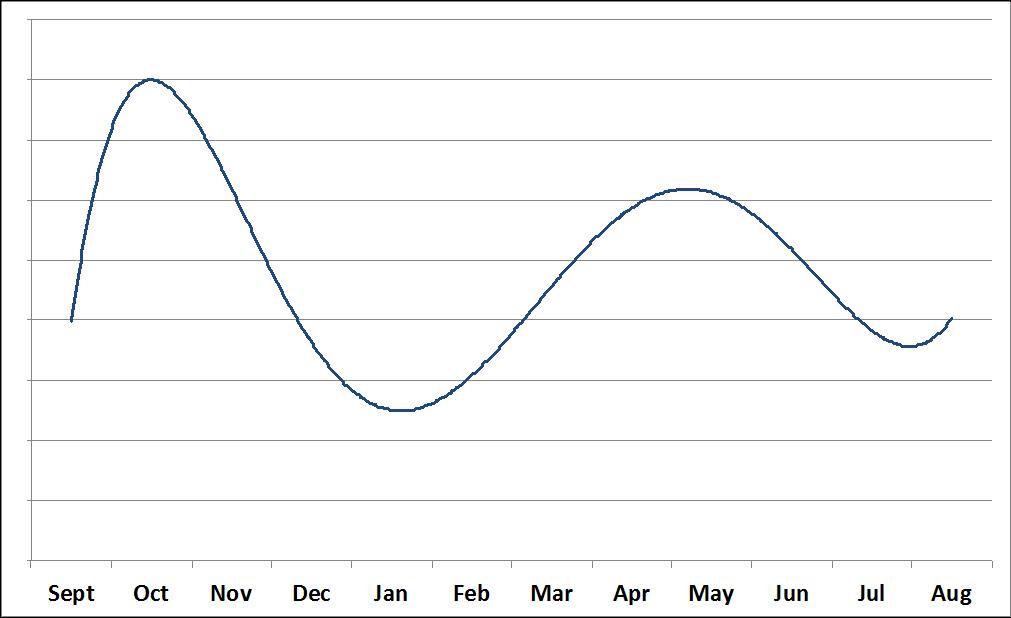

The bulk of the hay trade occurs at baling but depending on the timing and scale of the autumn break, April and May can be another peak trading period for hay growers.

Figure 3: Typical hay trade volumes.

Hay prices are volatile but no more so than wheat prices. Droughts particularly from 2002 to 2008 have changed the buying behaviour of many hay buyers. Hay has been the greatest limiting factor for many dairy farmers during these dry times. Dairy farmers tend to be the most astute group of buyers as their margins are tight and the optimum nutritional performance of their cows is paramount. Dairy farmers of the irrigated north in particular have tended to become both savvy buyers and more self-reliant for their hay needs by purchasing more land to grow their own hay.

The insecurity of supply and necessity to enter the market and haggle each year with sellers is shifting some buyers away from hay purchases and into more home-grown fodder supplies. Dairy farmers tend to have the capacity to blend co-product feeds to create a ration and buy on the nutritional merits of hay. Beef and sheep farmers tend to have less feed mixing equipment and are less driven by the quality attributes of hay on offer.

Cereal hay quality is heavily influenced by the time of cutting, which is optimum at Zadoks Growth Stage 65 to 71.

Hay export

With many countries in north Asia and the Middle East striving for self-sufficiency in their dairy and beef production, the global trade of hay is expanding. This year total traded hay is expected to be 50 per cent greater than in 2007. Increasingly countries aspire to retain self-sufficiency in dairy and beef production via imports of roughage feeds which countries are unable to grow themselves.

Australian hay exporters have worked hard to establish markets for oaten hay, which is Japan’s largest single hay commodity imported. Japan remains the dominant buyer of hay for dairy and beef herds however China and the UAE are now competitive buyers of lucerne and oaten hay.

The eight-hay export processing plants that buy cereal hay and straw in Victoria and Southern NSW represent around a third of the processing capacity in Australia. Each has different buying grades and pricing scales although there are some general similarities in the hay grades.

Table 1: General hay quality requirements for export markets.

| Parameter | High quality | Low / Med Quality | 2015 quality reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Soluble Carbohydrates | 15-25% | 5-15% | 25-35% |

| Digestibility | 60-65% | 55-60% | 65-70% |

| ADF | 30-35% | 35-40% | |

| NDF | 50-55% | 55-60% | 47-50% |

| Crude protein | 4-8% | 4-8% | 9-11% |

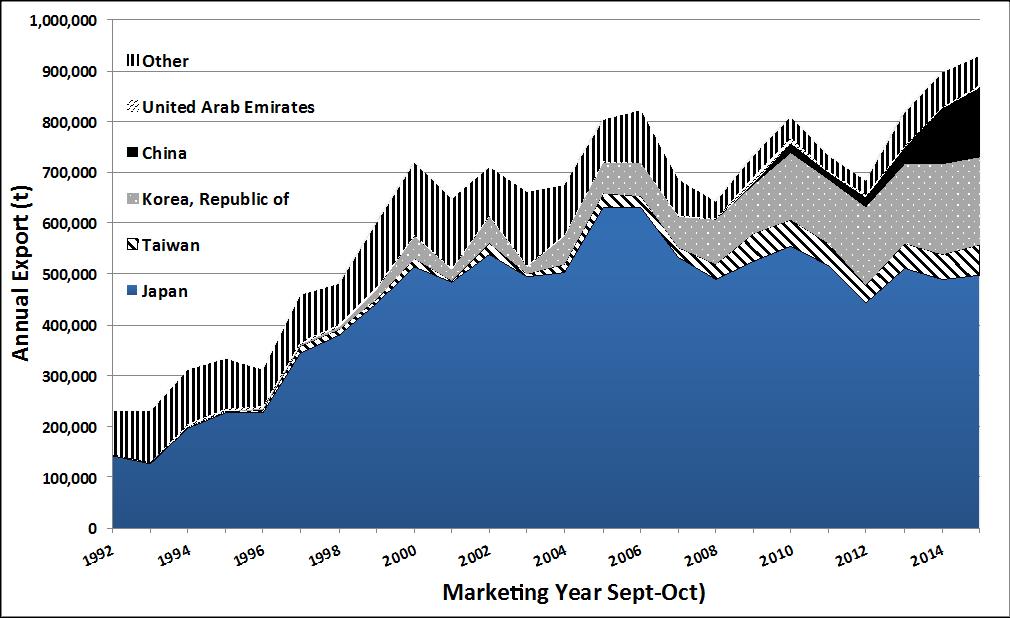

Victoria and NSW export around 20 per cent of Australia’s hay with Western Australia exporting 45 per cent and South Australia exporting 33 per cent. Japan has been underpinning the export hay demand since it began in the mid 1980’s but is now a mature market and declining due to reducing profitability for dairy farmers in Japan.

South Korea has expanded its imports of Australian oaten hay and straw over the past 10 years. But it has been the rapid expansion of hay demand from China, which has captured the imagination of many in the trade.

Figure 4: Australian export hay by destination.

Chinese hay demand

With 20 per cent of the world’s population and only 6 per cent of its arable land, China has strategically focused its own agriculture on production of human food. Animal feeds have been a target for import.

While Australia has 1.69 million dairy cows, China has around 15.6 million. The strong economic growth, a large young population, expanding middleclass and Government sponsored school milk programs have increased the demand for dairy products in China. Chinese dairy consumption is only a third of the world average and has a large capacity to increase. China still produces half of its milk from herds under 10 cows.

In 2008 melamine contamination of dairy feeds led to the death of six babies and caused illness in over 50,000 others. This triggered distrust of Chinese dairy products, a culling of around 15 per cent of the Chinese herd (mainly small herds) and expansion of dairy imports.

More recently milk production reduced 5.7 per cent in 2013 and rebounded in 2014 creating a glut of milk in 2015. Analysts predict that this oversupply of milk should be cleared near the end of 2016. Despite this glut of milk, the Chinese dairy industry continues to modernize with small herds exiting the industry and the large herds expanding. Chinese dairy producers are favoured by the demand for fresh milk, which represents over 80 per cent of total dairy demand.

Modern Chinese dairies are employing animal nutritionists and are increasing their per cow milk production. This favours demand for oaten hay. China now imports Australian oaten hay at a rate of ~185,000t/year. China does not import other cereal hay, cereal straw or lucerne from Australia although attempts are being made through the Australian Fodder Industry Association to gain access for these additional commodities.

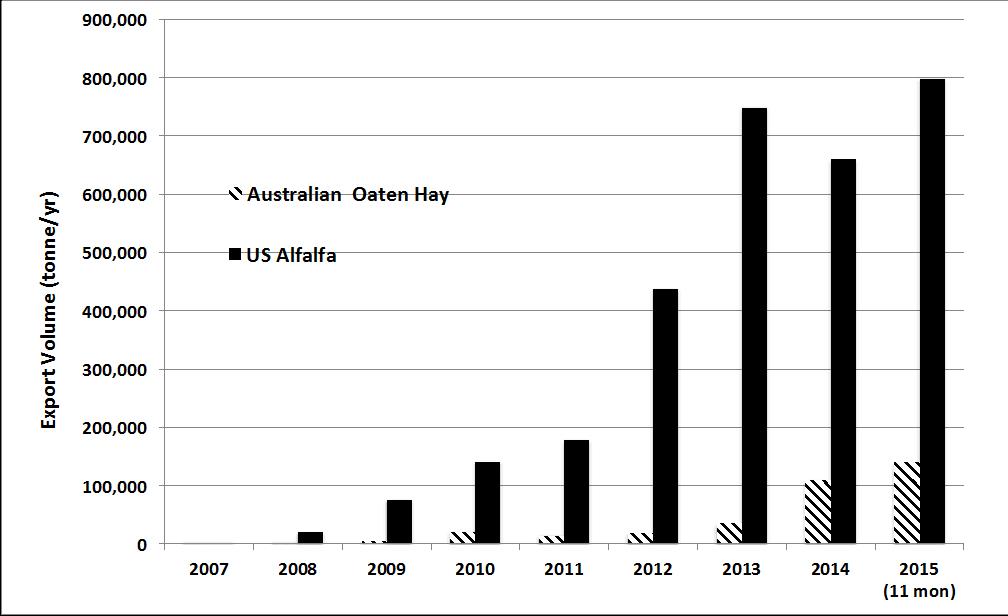

Imports of Australian oaten hay are still dwarfed by imports of alfalfa or lucerne hay mainly from the US, which sit at around 800,000t. The role of oaten hay has been to provide a palatable fibre to improve rumen function and balance the ration with US alfalfa.

Figure 5: Chinese imports of oaten hay and US alfalfa hay.

Market outlook

With the new season opening milk prices of $4.45 to $5.00 per kg of milk solids, dairy farmers and consultants are saying milk prices will be under the cost of production for some dairy enterprises.

Broad-acre croppers who are growing hay primarily as a cash crop, see their dairy clients as a critical sector that underpins their annual sales.

Just how dairy farmers will cope with the lower prices and how their budgetary changes will impact on their buying behaviour remains unclear. Rather than building hay stocks and in order to avoid spending money on hay that they may not use in 2017, some industry analysts have suggested that dairy farmers are likely to make just enough hay for the feed gaps of a typical season.

A discouraging hay demand outlook from the dairy sector may also encourage some vetch growers to plough their crops in rather than cut for hay. This would be more likely if these growers have hay shed space that they would like to free up for their expanded export oaten hay commitments. Irrigated lucerne hay growers in Northern Victoria are also reducing their production due to the dairy 'crisis' and high cost of irrigated water.

This could provide some opportunities for vetch and oaten hay sellers as tight hay stocks could remove any supply buffer. The new season will be opening with some of the lowest stocks of carryover hay since 2010. If this combines with some lean hay production from the dairy sector and a late break in 2017, the hay market may be vulnerable to some spikes in demand.

But prices are likely to fall. Hay sellers may find they could face stronger demand if the opening prices for hay are much cheaper than current rates. If pasture and cereal hay prices are well under $200 a tonne delivered farm, it may be financially prudent for dairy farmers to buy hay and maximize the grazing from the home-grown pastures.

Conclusion

Given the shift to shorter winter growing seasons, hay will continue to be an option for grain growers. Success can be improved with some awareness of the scale of Victorian pasture production and the quality needs of hay buyers.

Export hay volumes are growing particularly to China and South Korea. With planning and forward contracting paddocks with an exporter, oaten hay can be a valuable part of a cropping program if partnered with domestic sales.

Like other countries around the world, the Victorian dairy sector is under significant pressure with low milk prices. A broad mix of hay buyers may be a valuable strategy for 2017.

Useful resources

Producing Quality Oaten hay (Pamela Zwer, Mick Faulkner)

Contact details

Colin PeacePO Box 2252, Hawthorn, Vic, 3122

0413 835793

colin@jumbukag.com.au

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK