Aphids, natural enemies and smarter management

| Date: 23 Feb 2010

Aphids, natural enemies and smarter management

Kym Perry, Ken Henry, Judy Bellati (SARDI), Stuart McColl (CESAR Consultants) and Paul Umina (CESAR)

Aphid biology

Aphids are soft-bodied insects with piercing and sucking mouthparts, which they use to penetrate plant tissue and extract sap. They have complex lifecycles, including both sexual and asexual reproduction, and the production of winged (alate) or wingless (apterous) adult forms. In the warm Australian climate, the sexual phase is reduced and reproduction is almost entirely asexual, with females giving birth to live female offspring that are already carrying development embryos. This ‘telescoping’ of generations allows aphids to reproduce very rapidly when conditions are favourable. Aphid survival, development and population growth are strongly influenced by local environmental factors; cooler temperatures or significant rainfall slow rates of aphid development while warm and relatively dry conditions favour rapid population build-up.

Lifecycle

Aphid populations survive over summer on alternative host plants such as weeds in roadside vegetation and verges. In autumn, winged adults move into crop edges where they build up in numbers before moving into other parts of the crops. The timing and number of aphid flights into crops are influenced by late summer- and early autumn- rainfall; good rainfall favours growth of suitable host plants and allows aphids to build up early in the season. During the cool winter months, rates of aphid development are slow. Spring triggers a rapid increase in rates of aphid development, when reproduction and population expansion occurs very quickly. Aphids often form dense colonies on the growing points of individual plants before moving onto surrounding plants; therefore aphid infestations often occur in patches or ‘hotspots’ within paddocks.

Feeding and virus damage

Aphids damage crop plants directly through feeding which removes plant sap and nutrients, leading to wilting and yellowing of plants, and through secretion of honeydew, which supports secondary growth of sooty mould. Aphids also cause indirect crop damage through the transmission of plant virus diseases. Direct feeding damage usually only occurs when aphids are in high populations, however substantial plant damage can result from plant viruses transmitted by relatively few aphids. Aphids transmit viruses by feeding (or probing) on infected plants and soon after, feeding (or probing) healthy plants. Viruses transmitted non-persistently are carried temporarily on the stylets and will transmit (instantly) to only the next plant that is probed. Persistent viruses remain in the salivary glands of the aphid for life, which can transmit the virus to multiple plants. Acquisition of persistent viruses by aphids requires 1-2 hours of active feeding on infected plants, followed by a latent non-infective period of 12-24 hours. Transmission to healthy plants occurs after 5-10 minutes of active feeding.

Species identification and crop hosts

There are a number of aphid species that attack field crops in Australia (Table 1). Aphids have a pair of wax-secreting tube-like projections called ‘siphuncles’ (or ‘cornicles’) at the rear of the abdomen. These often vary in size and shape and can be a characteristic feature for distinguishing between species. Species identification in the field is usually important because management strategies will vary. Only certain species will transmit plant viruses to particular crop types. Some species have also developed resistance to multiple chemical classes; hence selection of insecticides for controlling these species must be carefully considered. Because aphid species are generally crop-specific, correctly identifying aphids (particularly those on weeds and volunteer hosts) can also be used to predict the level of pest problems likely to be encountered on any given crop.

Aphid natural enemies

There are a number of beneficial natural enemies that attack aphids, including host-specialised parasitic wasps, as well as generalist predators such as hoverfly larvae, and adults and larvae of ladybird beetles and lacewings. These can provide a reliable form of biological control for moderate numbers of aphids, and help keep them below economically damaging levels. Beneficial insects are present in crops throughout the season but become prevalent in spring when their host prey abundance increases and when warmer conditions favour more rapid development.

When monitoring for aphids, it is important to record and consider the numbers of beneficial insects before deciding to spray. The presence within crops of aphid ‘mummies’, which appear bloated with a pale gold or bronze sheen, indicates beneficial parasitic wasp activity. Hoverfly larvae appear maggot-like with a whitish strip down the centre of the back, while ladybird larvae are highly mobile, elongated and have well-developed legs, which appear quite different from the small, shiny and rounded adult beetles. Only brown lacewing adults are predatory, however the larvae of both green and brown lacewings are highly voracious predators. Lacewing adults are 10-20 mm long, have prominent eyes, long antennae and a fluttering style of flight. Larvae are up to 8 mm long and have protruding sickle-shaped mouthparts and a tapering body.

It is important to realise that there is often a ‘lag’ time between pest population growth and increases in the abundance of their natural enemies. If monitoring detects beneficial activity in crops, it is often advisable to hold off spraying and assess whether they can suppress pest numbers enough to avoid the need for a chemical treatment. Providing refuge habitat (e.g. remnant vegetation, trap crops) and alternate food sources (e.g. nectar sources, non-pest hosts) are relatively simple ways of maximising the use of naturally occurring biological control.

Management of crop aphids

Monitoring and thresholds

Monitoring and early detection of crop aphids is a key to effective management. Regular monitoring of most crops should commence in late winter and early spring, and continue through until late flowering. Standard recommendations for aphid monitoring are to check representative parts of entire paddocks along with any patches of wilted or stunted growth. Inspections should include at least five points within each paddock and look for aphids on a minimum of 20 plants at each point.

Economic thresholds (ETs) relate to the density of a given pest at which the cost of potential crop damage equals the costs of treatment (chemical + application costs), and provide a guide for growers to decide whether to implement control. ETs are quantitative measures and usually specified as the number of pests found per unit of crop area using a specified (standard) sampling technique. Yield loss and quality reduction are usually the critical factors governing control decisions. Unfortunately the lack of entomological broad-acre research in the southern grain belt over the last couple of decades has seen many ETs become outdated and somewhat irrelevant to current economic costs and management practices.

For aphids, there are some threshold recommendations available for Australian field crops that are based on research conducted in Western Australia (feeding damage only; in the absence of viruses). For cereals, consider control if 50% of plants have at least 15 aphids per tiller, for crops expected to yield at least 3 tonnes/ha. For canola, consider control if at least 20% of plants are infested. For lupins, control measures should be implemented if more than 30% of growing tips are colonised by aphids from the flower bud stage through to podding, particularly in aphid-susceptible varieties.

It is important to realise these thresholds are a guideline only and will vary considerably with agronomic factors such as crop growth stage, yield potential and vigour, as well as local weather conditions and moisture levels, and economic factors such as market value (grain prices), and chemical and application costs. Slightly moisture-stressed plants are often less able to compensate for aphid feeding damage compared with healthy plants. These thresholds need constant revision and updating to reflect changes in these factors over time and between regions.

Correct chemical use and spray timing

Insecticides should be chosen carefully and used strategically for effective management of aphids. It is often not necessary to treat entire paddocks as aphid infestations often start at crop edges. If aphids are detected early, often a border spray with an aphid-specific insecticide (e.g. pirimicarb) will provide good control of aphids whilst minimising harm to beneficial insects within the crop. The use of synthetic pyrethroids is not recommended as it is largely ineffective in directly killing aphids (anti-feedant properties only), selects strongly for insecticide resistance in aphids and non-target species, and will kill many natural enemies. The use of some insecticide-based seed dressings may prevent aphids from entering crops for up to six weeks after emergence, delaying the need for foliar sprays.

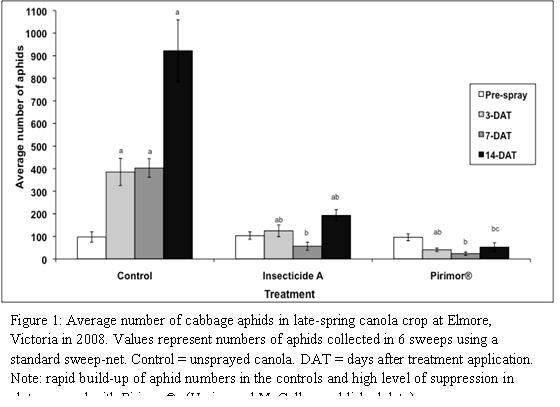

The importance of correctly timing insecticide applications to control aphids should not be under-estimated. If combating viruses and applying insecticides in autumn, sprays should be applied soon after aphids start moving into crops from surrounding vegetation. Waiting too long could result in a substantial number of plants becoming infected, which is likely to result in larger issues with viruses as temperatures increase in spring. Remember that the application of broad-spectrum insecticides early may result in a later reinfestation because small numbers of surviving aphids are no longer controlled by natural enemies. Timing of insecticide applications in spring is also critical. Spraying too early (before significant aphid ‘flights’ have occurred) can be a waste of product and disrupt natural enemies present. However, aphid populations can reach damaging levels very rapidly under ideal conditions; therefore, if spraying is required, it is important to apply before this time (see Figure 1).

Aphid management in virus-prone areas

In virus-prone areas, monitoring should commence earlier in the autumn, as early viral infection can be most damaging. Monitor crops from emergence and weekly afterwards for signs of aphid colonisation, particularly in crop edges. The use of yellow sticky traps or pan traps can assist in early detection of aphids and assessment of numbers. Prevent aphid build-up in nearby weeds and other vegetation ‘green bridges’ to lessen the risk of nearby flights. Consider the use of seed dressings to prevent aphid building up in emerging crops early in the season.

Suggestions for aphid management in chickpeas

Chickpeas are distinct from other pulses in that they are poorly colonised by aphids. Rather, aphids probe plants briefly before moving to other plants within the crop looking for a colonisable host, which has implications for virus transmission and aphid management. Spraying for aphids is generally not recommended or considered worthwhile as there is little colonisation of crops by aphids, and insecticides will not prevent aphids that subsequently migrate into the crop from feeding and transmitting viruses. Therefore, strategies should focus around minimising aphid movement into chickpea crops. Some strategies may include:

· Retain standing stubble to deter migrant aphids from landing in crops.

· Control broadleaf weeds to remove adjacent sources of aphids and virus, particularly AMV and CMV (non-persistent).

· Plant chickpeas some distance away from lucerne paddocks, which is a perennial host of legume aphids and virus (AMV and the persistent BLRV).

· Use of border rows of non-hosts to limit the degree to which immigrating aphids introduce non-persistent viruses into crops.

A review of pest occurrences in 2009 and ‘PestFacts’ services

PestFacts is a free service designed to keep growers and advisers informed about pest-related issues – and solutions - as they emerge during the growing season. It is distributed as an electronic newsletter and aims to help growers achieve maximum yield and quality for the lowest cost by providing timely information about pest outbreaks, effective controls and information about relevant and new research findings. To provide this service PestFacts draws on the field observations of consultants, growers and industry specialists across south-eastern Australia as they report on the location and extent of invertebrate outbreaks. It also issues warnings (or reminders) for a range of invertebrate pests of all crops, including pulses, oilseeds, cereals and fodder crops.

PestFacts is part of the GRDC-funded National Invertebrate Pest Initiative (NIPI), designed to help advisers and growers deal with the increasing challenges being presented by mites and insects. It is based on the PestFax model that has run successfully in WA for many years.

The information generated by PestFacts can also be used to gain an idea of the occurrence and location of pest problems. This provides an opportunity for awareness, discussion and ongoing evaluation of changing pest importance. Table 2 shows the invertebrate pest reports received by the PestFacts services for Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia in 2009. Aphids, mites and several caterpillar species were significant pests in 2009.

Useful references:

Berlandier F. Aphid management in canola crops - Farmnote

Berlandier F. Aphids in lupin crops: their biology and control - Farmnote

Bray T. Virus control and aphid monitoring simplified. Australia Pulse Bulletin.

Edwards O, Franzmann B, Thackray D, Micic S, (2008). Insecticide resistance and implications for future aphid management in Australian grains and pastures: a review. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 48, 1523-1530.

Schwinghamer M, Knights T, Moore K. Virus control in chickpeas – special considerations. Australia Pulse Bulletin.

PestFacts South-Eastern

http://cesarconsultants.com.au/services/agriculture.html

PestFacts SA and western Victoria

http://www.sardi.sa.gov.au/pestfacts

Crop insects: The Ute Guide (Southern Grain belt edition)

http://www.grdc.com.au/director/events/bookshop?pageNumber=2&category=204

Contact details:

Kym Perry Ph: 08 8303 9370

Email: kym.perry@sa.gov.au

Ken Henry Ph: 08 8303 9540

Email: ken.henry@sa.gov.au

Judy Bellati Ph: 08 8303 9670

Email: judy.bellati@sa.gov.au

Paul Umina Ph: 03 8344 2522

Email: pumina@unimelb.edu.au

Stuart McColl Ph: 03 9329 8816

Email: stuart@cesarconsultants.com.au

GRDC project codes:

CSE00046

UM00033

Table 1: Crop hosts and distinguishing features of the major aphid pests of field crops in southern Australia.

|

Aphid

|

Crop hosts

|

Adult size & colour

|

Key features

|

Colony habit

|

|

Cereals

|

||||

|

Oat aphid

Ropalosiphum padi

|

Mainly oats and wheat; can infest all cereals and grasses

|

2mm, olive-green to black

|

Rusty red patch at the base of the abdomen between the siphuncles

|

Develop on stems, leaves and heads, usually from the base upwards

|

|

Corn aphid

Ropalosiphum maidis

|

Mainly barley; can infest all cereals & grasses

|

2mm, light-green to dark olive-green

|

Dark purple patches at the base of each siphuncle

|

Develop within the furled tips of tillers

|

|

Canola

|

||||

|

Cabbage aphid

Brevicoryne brassicae

|

Canola, some cruciferous forage crops

|

3mm, dull or greyish-green

|

Siphuncles short, blunt and swollen distally. Covered with a thick whitish powder. Colonies appear bluish-grey

|

Dense colonies on terminal flower spikes

|

|

Turnip aphid

Lipaphis erysimi

|

Canola, other brassica crops

|

3mm long, olive to greyish -green

|

Siphuncles longer and pointed. Light covering of wax.

|

Dense colonies on terminal flower spikes

|

|

Green peach aphid

Myzus persicae

|

Lupin, canola, some pulses, some cruciferous weeds

|

3mm long, pale yellow-green, green, orange or pink

|

Tubercles (small humps between antennae) turned inwards

|

Sparse colonies, usually on underside of lower leaves.

|

|

Pulses and other crops

|

||||

|

Cowpea aphid

Aphis craccivora

|

Lupins, some pulses, medics

|

Adults shiny black

|

All stages have black and white banding on the legs

|

Dense colonies form on the growing tips

|

|

Bluegreen aphid

Acyrthosiphon kondoi

|

Lupins, lucerne, medic & sub clover pasture

|

3mm, grey-green to blue - green

|

Long siphuncles and antennae

|

Don’t usually form large colonies

|

|

Pea aphid

Acyrthosiphon pisum

|

Lucerne, faba beans, field peas

|

Similar to blue green aphid

|

All stages have black knees and dark joints between antennal segments

|

Colonies may form as numbers build up

|

Table 2: Invertebrate pest reports in 2009 in SA, NSW and Victoria from ‘PestFacts SA and western Victoria’ and ‘PestFacts South-Eastern’.

|

|

Species

|

Total

|

May

|

Jun

|

Jul

|

Aug

|

Sep

|

Oct

|

Nov

|

|

Seedling establishment pests

|

|||||||||

|

Mites and Lucerne Flea

|

Redlegged earth mite

|

19

|

6

|

3

|

10

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

Blue oat mite

|

16

|

9

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

0

|

|

|

|

Lucerne flea

|

12

|

8

|

3

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

Bryobia mite

|

26

|

7

|

18

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

Balaustium mite

|

2

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

Caterpillars

|

Yellowheaded cockchafer

|

5

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

|

|

Blackheaded cockchafer

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

Pasture day moth

|

6

|

0

|

1

|

3

|

0

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

Pasture tunnel moth

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

|

|

Cutworms

|

5

|

5

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

Pasture webworm

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

Underground grass grub

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

|

Beetles

|

True wireworm

|

3

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

Bronzed field beetle

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

False wireworm

|

7

|

4

|

1

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

Others

|

Slaters

|

16

|

4

|

7

|

5

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

Slugs

|

5

|

5

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

Sawfly larvae

|

4

|

0

|

3

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

Grain formation pests

|

|||||||||

|

Aphids

|

Cereal aphid

|

38

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

6

|

26

|

3

|

0

|

|

|

Cabbage aphid

|

8

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

4

|

0

|

|

|

Cowpea aphid

|

13

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

9

|

0

|

1

|

|

|

Blue green aphid

|

9

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

6

|

0

|

2

|

|

|

Corn aphid

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

|

Caterpillars

|

Native budworm

|

17

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

12

|

1

|

|

|

Armyworm

|

26

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

10

|

6

|

7

|

1

|

|

|

Diamond back moth

|

18

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

11

|

2

|

5

|

|

|

Grass anthelid

|

11

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

2

|

2

|

3

|

3

|

|

|

Brown pasture looper

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

Others

|

Rutherglen bug

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

Australian plague locust

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

|

|

Wheat curl mite

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

|

European earwigs

|

5

|

0

|

0

|

5

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

GRDC Project Code: CSE00046 UM00033,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK

To protect your privacy, please do not include contact information in your feedback. If you would like

a response, please contact us.