CROPPING LAND LEASING - PRINCIPLES FOR SUCCESS

| Date: 01 Sep 2010

Introduction

A farm lease is a contract between a tenant, also known as the lessee, and a landlord, also known as the lessor, allowing rental of land for an agreed price for a fixed term. The general principle of a farm lease is that the landlord foregoes the opportunity to utilise the land resource in return for a fixed or guaranteed rental payment from the tenant. In return for the rental payment the tenant is able to utilise the land and other farm infrastructure to generate income from farming activities. The usual agreement is that the tenant is entitled to 100 percent of the income generated from the farming activities.

Typically, the landlord is responsible for the provision of the fixed assets and infrastructure such as the land, fences, yards, buildings and sheds. The landlord is usually responsible for the payment of council rates and insurance of fixed assets.

The tenant is usually responsible for general repairs and maintenance of fixed assets, the provision of the livestock and machinery assets if required, as well as provision of labour and payment of the operational costs incurred in generating a return. Tenants are responsible for insurance of their livestock and machinery assets and public liabilities.

Variations to these general principles do occur by mutual agreement between the landlord and tenant where there is a benefit for both parties. The implications and value of changes for each party needs to be clearly understood.

The advantages of leasing

Leasing presents tenants with an opportunity to engage in the business of farming without the high capital expense of land ownership. It therefore allows an entry point or expansion for a farming venture which might otherwise be impossible due to the large capital cost of a land acquisition.

As well as the lower capital costs leasing provides tenants who have existing landholdings with the chance to expand their farming operations with lower additional overhead costs. This provides an advantage in scale by spreading the same amount of overhead costs over a greater number of production units.

The extent of the advantage of scale is often overstated. This occurs because farm labour, which usually accounts for the greatest proportion of overhead expenses, is either used inefficiently or undervalued.

The disadvantages of leasing

Leasing provides tenants with an opportunity to be rewarded for their farm management ability but there are downside risks that come with leasing as well.

1. There are no capital gains in leasing – the surest way to acquire wealth in agriculture over the long term.

2. There is higher finance risk because there is a cash cost associated with the use of the land (the rent) and subsequent losses if they occur may not be backed by a large asset base which can be drawn down on.

What are the features of a successful lease?

The term of the lease is sufficient that the tenant can implement a management program and benefit from the investment over a period which is long enough to allow a few good years (combination of markets and seasons).

The landlord and the tenant have an understanding and mutual respect for each other’s objectives. As capital gain is the primary objective of the landlord and operating profit is the primary objective of the tenant neither puts unnecessary hurdles in place to prevent the objective from being met.

The landlord does not rely on the tenant as a source of property improvement. The landlord will either make some effort to invest in land improvements or not have unrealistic expectations of the tenant to do so. The tenant may wish to include property improvements that provide mutual benefit (e.g. pasture improvements and infrastructure improvements) so long as there is sufficient time to generate a return on investment.

Landlords and tenants communicate in a clear and open fashion. This may require transparency of key productivity measures.

A procedure for getting it right – for the tenant

Lease opportunities present themselves in a range of different ways. These include newspaper or other media advertisements, targeted requests for expressions of interest from stock and station agents or consultants acting on behalf of clients, direct contact from potential landlords or referrals from neighbours.

The key issues that are important to the landlord when offering land for lease are:

• Engaging a tenant with good management skills

• Preserving or improving the land asset

• Generating a reasonable return

Any proposal therefore should focus on these areas and provide demonstrated management performance and demonstrated commitment to preserving or improving the land asset.

What to pay for leases

A critical question regarding cropping leases is “what is it worth?” It is not uncommon for farm business managers to enter into lease agreements with inadequate analysis. The result is usually a lease payment well in excess of that required to make a profit and so those farmers employ more resources and work a whole lot harder for no additional reward.

Assuming that leasing additional land is a business proposition, leases should be priced using economic rather than market valuation. That is, the lease price should be dependent on the return that is required from the investment not on what the market dictates. In order to estimate the return generated from the lease, it is necessary to estimate the level of productivity and the costs to generate that productivity. Based on this methodology a lease can be valued per unit of production.

Economic valuation is not clear cut because returns are a subjective issue. That is, the level of return that is considered acceptable to one manager may be considered unacceptable to another. Further, a business with very low operating scale may be willing to pay more for a lease than a business with high scale as the value of the marginal benefits are greater. This subjective element suggests that there is no “one-size-fits-all” lease figure. A range with upper and lower limits however can be determined and will help as a guide.

Lease valuation methodology

There are two broad methods by which lease arrangements are made for cropping land. The first is on a percentage of capital value and the second is on a fixed charge per hectare or per tonne of yield potential.

The percentage of capital value approach usually favours the landlord (or lessor), but can be attractive to the tenant (or lessee), in terms of its simplicity. Most landlords seek approximately 5% or more of the capital value of the land to be paid either as a single figure in advance or in a series of monthly or quarterly instalments in advance.

If the land is valued at say $3000 per hectare and a lease rate of 5% is charged then the annual fee payable is $150 per hectare. If this land is to be leased to grow wheat and the wheat yield potential is 2.5 tonnes per hectare then there is a charge against the wheat enterprise of $60 per tonne of wheat produced. Can this charge be borne and still allow the enterprise to be profitable or is it out of the question?

There are several problems with employing this methodology for determining the lease rate.

1. Valuing the capital value of the land

2. The rate of increase of capital growth

3. The return generated by the land

Valuing the capital value of the land can be a bone of contention. If the property has been recently sold then it can be relatively easy to determine the market value. However where this is not the case there can be problems as land owners tend to think that their land is worth a lot more than the market value. They can always justify their idea of their land value – better soil, more rainfall, better improvements – but the reality is that the market doesn’t necessarily view it the same way as they do.

The next problem with the percentage of capital value approach is that rapid increases in capital value of the land increase the lease rate but don’t necessarily relate to the productive potential of the lease. Consider what would occur if the capital value of the land increased by 50% as occurred in the land market recently. In our previous case the land value would increase to $4,500 per hectare and the lease rate would increase to $225 per hectare even though there is no change in productive potential. This makes no economic sense.

Valuing cropping land for leasing

A commonly used methodology for determining the economic value of leasing additional agricultural land is to calculate the internal rate of return. An internet based tool has been provided to participants of the “Principles of profitable farm leasing course” held by Holmes Sackett to allow for the calculation of the internal rate of return on lease rates. The tool allows for the entry of a typical rotation, the costs associated with growing the crops, the average yield and the price. The tool generates the internal rate of return so that the user can assess the economic viability of the lease.

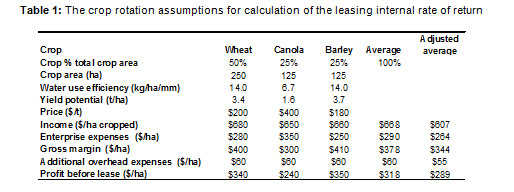

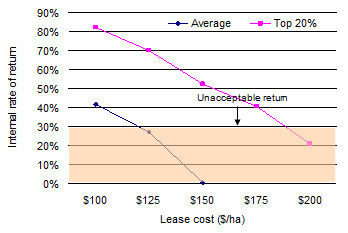

The internal rate of returns from varying lease costs (shown in graph 1) have been calculated from a 5 year projected cash flow of a wheat, barley, canola rotation with respective crop areas of 50%, 25% and 25%. This provides an indication of the return on investment over the assumed lease period of 5 years. The input assumptions into the analysis can be seen in table 1. Of particular note is the average rotation return. This accounts for all of the crops in the rotation over the term of the lease and, in this case, is lower than the cereal returns.

The key consideration in the five year cash flow is the return generated over time relative to the up-front cost. Cropping leases provide reasonable returns as a rule because they have relatively low up-front costs. In this analysis it has been assumed that 60% of the total overhead costs and enterprise expenses are spent prior to sowing the crop.

The internal rates of return from varying lease costs with top 20% management and average management are shown in graph 1. The water use efficiencies of 14 kilograms per hectare per millimetre for cereals and 6.7 kilograms per hectare per millimetre for canola (shown in table 1) suggest that the yields projected are a function of top 20% management. The Holmes Sackett benchmarking data suggests that average managers achieve water use efficiencies of closer to 12 and 6 kilograms per hectare per millimetre for cereals and canola respectively.

While the return required from the lease is a subjective issue it is suggested that a target of 30% be set given the level of risk involved. Graph 1 shows that the average manager cannot afford to pay any more than $120 per hectare for a lease to provide an internal rate of return of 30%. The manager with top 20% performance at the same lease price achieves internal rates of return above 70%. The manager with top 20% performance can pay up to $70 per hectare more than the average producer before returns drop below 30%. This demonstrates the effect that management has on the amount that can be paid for a lease. It also shows that optimising productivity is essential when leasing due to their sensitivity to different levels of production.

The adjusted average shown in table 1 accounts for the fact that not 100% of the total area leased can be cropped. In this case 90% of the total area leased is arable and cropped. The implication of this is that the lease is paid on 100% of the land but profit is generated on only 90% of the land. The total area that can be used to generate profit needs to be taken into consideration when leasing.

Figure 1: The average manager cannot afford to pay the same lease rate as the top 20% manager

The $190 per hectare lease rate that provides the internal rate of return of 30% with top 20% management is specific to this scenario and does not necessarily have broader application. The outcome is dependent on the lease cost, input costs, additional overhead costs, the level of productivity and the percentage of total area cropped. The Holmes Sackett lease valuation tool is available to participants of the “Principles of successful farm leasing” workshop and allows for assessment of lease returns tailored to individual circumstances.

Contact details

John Francis

Director

Holmes Sackett

Ph: 02 6931 7110

Email: john@hs-a.com.au

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK