Is agricultural land a good investment. Decisions on farm land tenure: buying, leasing and the alternatives

Author: Duncan Ashby (RG Ashby & Co.) | Date: 10 Mar 2016

Introduction

A farm business is comprised of land and working capital, and the returns from each combine to produce the overall return to the business. The traditional model is an investment in land (ownership) and working capital. If this business has the scale and structure required, then both can produce a return. However many farm businesses in Australia make no money from their working capital and rely on land appreciation.

The options for alternate forms of land tenure require the separate analysis of the risk faced and return generated from the land asset and the working capital. Land tenure agreements can allow an older farmer to reduce the production risk faced and working capital required, while still generating income and retaining ownership of the land. While young farmers or those looking to expand their operations can use land tenure agreements to secure access to land and focus their investment on working capital.

This paper addresses decisions around land tenure that farm businesses can make and the implications this has for their farmers at different stages of their career and for the agricultural sector.

There are a range of alternative forms of land tenure available other than owning, but their use in Australia is very low compared with the farm business sector in many countries. While it has been growing there is huge scope for it to play a bigger role and for certain models to be structured to meet the requirements of groups at very different stages in their careers, such as new farmers and retiring farmers.

| Year | Number of farms | Farm area (million hectares) | Wheat and crop area (million hectares) | Beef (million cattle) | Dairy (million cows) | Sheep (million head) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973/74 | 189,000 | 500 | 13 | 27 | 4 | 145 |

| 2013/14 | 120,000 | 397 | 25 | 25 | 3 | 73 |

Farm businesses that are not pro-active will not be able to develop the economies of scale required to generate profits and increase the size of their farm business. Poor profitability among small farm businesses drives the process of farm consolidation that continues to be a long-term trend in Australian farming.

Some pre-empt change, some respond to change and some have change thrust upon them (modified from William Shakespeare, The Twelfth Night)

The farm businesses that will have change thrust upon them include all of those without the scale to regularly generate profits and the ability to create additional profits through other strategies. This is not intended as a return to the ‘get big or get out’ mantra, but instead as an acknowledgement that broadacre cropping farm businesses exposed to commodity markets with no premium generation strategy (branded product or unique traits) must have scale to create profits.

How are Australian farms performing? A review of the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics (ABARE) Farm Survey results indicates that:

- most farms are small and unprofitable (and these farms must not continue business as usual)

- farm returns are very variable

- land values rose above trends, but are now falling back.

Any farm business that has not been able to consistently generate more profit than they would have received from leasing their land must consider their land tenure options, to both secure a return and to manage their production risk. Specifically, they would be better off leasing the land out.

Land tenure trends in Australian broadacre agriculture are:

- Leasing is five to seven per cent of farm land, but has been increasing in some areas

- share-farming is utilised but on a very limited scale

- other options are confined to a small number of farmers who are comfortable with their use from previous experience – these alternatives receive limited coverage from advisers.

How does farm land compare and contrast with other investment options

Economic conditions since the GFC have reduced returns from a range of asset classes, and continued weakness in the world economy has further damaged sentiment. The gross returns for ASX investments in the 10 years to 2014 are now 7.1 per cent, and 7.0 per cent for residential property (compared with 9.5 per cent and 9.8 per cent for the 20 year average).

Meanwhile, the value of farmland has appreciated steadily if unevenly with cropping farmland appreciating by 8 per cent in 2013 and 6.4 per cent in 2014. More broadly, Victorian farmland increased by 11.6 per cent annually between 2000 and 2008 and by 4.2 per cent between 2008 and 2014. When farm income is added to this performance (2-5%) to make the measure comparable with the investment returns from the other asset classes, the retention of farmland is more appealing than in the pre-GFC environment.

| Asset class | Gross Returns for the 10 years to December 2014 | Gross returns for the 20 years to December 2014 |

|---|---|---|

| Australian Shares | 7.1% | 9.5% |

| Residential Investment Property | 7.0% | 9.8% |

| Australian Listed Property | 1.6% | 7.7% |

| Australian Fixed Income | 6.5% | 7.5% |

| Global Fixed Income (Hedged) | 7.6% | 8.6% |

| Cash | 3.4% | 3.7% |

| Global Shares (Hedged) | 7.8% | 8.6% |

| Global Shares (Unhedged) | 5.4% | 7.1% |

| Global Listed Property (unhedged) | 6.0% | 8.9% |

| Conservative Managed Fund | 6.0% | - |

| Balanced Managed Fund | 6.5% | - |

| Growth Managed Fund | 6.7% | - |

| CPI | 2.7% | 2.7% |

The ASX long-term investing report assumes all dividends are re-invested and is net of all costs before tax. It demonstrates the impact of the GFC and ongoing market uncertainty on the long-term returns for a range of asset classes.

Since this report was completed in December 2014 (ASX 200 = 5416), the ASX 200 has risen and then recently fallen below 5000. So the update for this report will be likely to show lower gross returns than in the 2015 update, at least for the ASX. In other more recent data, Balanced managed super funds (the mostly widely held super funds) returned 5.6 per cent (Source: Super Ratings).

Farm assets

The return from farming is made up of the return on the land assets and the return on working capital. Land values traditionally rise when interest rates are low and commodity prices are high.

| Years | Average annual growth (%) | Author's comments |

|---|---|---|

| 1990-2000 | 1.8% | A period of high interest rates and low commodity prices. |

| 2000-2008 | 11.6% | A period where commodity prices were improving and interest rates falling. |

| 2008-2014 | 4.2% | A period of low interest rates and moderate commodity prices. |

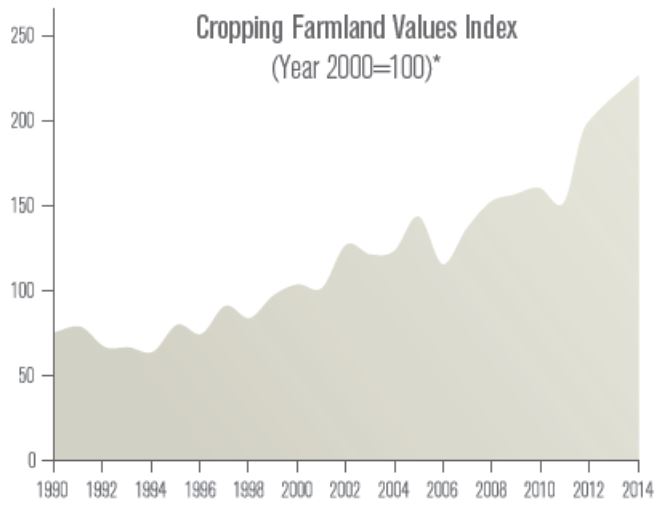

Like all asset classes, farm land has periods of stagnation and periods of growth and decline. However, the overall trend is for a consistent and steady increase in median values (see the cropping farmland values index). It has proved to be a good investment.

Figure 1: Cropping farmland values index. Source: Rural Finance Ag Answers – Victorian Farmland Values Index 2014.

Farm income - return on working capital

The other factor to include in assessing the return from farm ownership is the farm income. If we assume that farm income is between two and five per cent, then the overall return is in the range of eight to 13 per cent.

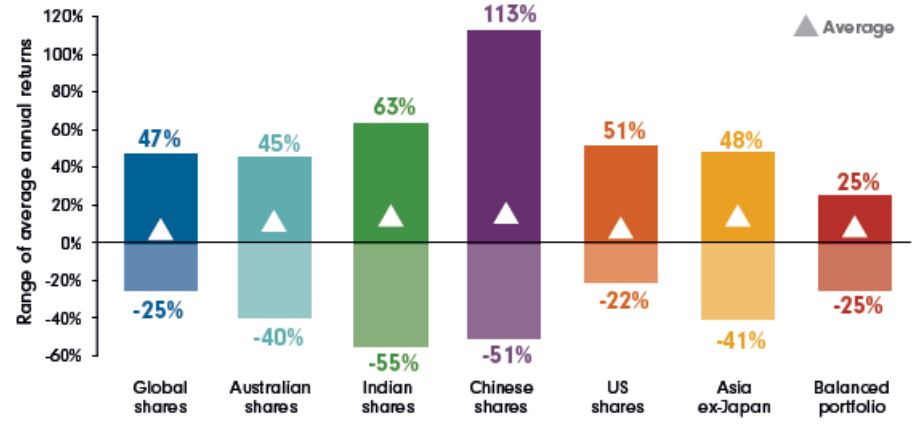

Figure 2: Range of one year returns – over the past 10 years to 30 June 2015. Source: Fidelity International.

Another factor in investments markets favouring farmland is that they have a low likelihood of a negative return (when including income and land appreciation) and they are not correlated with other asset classes.

Compare this to some of the negative ranges of one year returns (shown above) experienced by other asset classes in the 10 years to 30 June 2015 - 40 per cent for Australian shares.

Conclusion

- Farmland values have appreciated steadily over the long-term and compare favourably with long-term returns from other asset classes since the impact of the GFC, particularly when farm income (return from working capital) is included.

- The current economic conditions have reduced the incentives for retiring farmers to sell farmland and invest in a diversified portfolio of other asset classes due to the absence of compelling opportunities.

Key overseas land tenure models

On my recent Churchill Fellowship I investigated a range of farm models and alternatives for land tenure which balanced the returns made and risk faced from the investment in land ownership and in working capital.

Overseas farm land tenure models

- Employment model (Canada)

- Contracting

- Contracting – stubble to stubble (UK)

- Share farming

- Contract farming (NZ & UK)

- Flexible cash rents (USA)

- Leasing.

Key trends observed

- Leasing was an important part of farming in the UK, Canada and the USA where it covers between 40 and 60 per cent of farmland. A large feature of this was retired farmers, family members or widowers continuing to own the land and lease it out to local farmers.

- In the UK there is no correlation between the farm lease payment and the value of the land. Lease costs in the UK are often less than one per cent of the land value (where land averages £8000/acre).

- There was a widespread movement away from share-farming due to the associated ‘trust’ issues and a move towards leasing, or “cash rent” as they called it in the USA.

Useful application of these models in Australia

The contract farming agreement

The most appealing model I investigated was contract farming. While it has been used in Australia in some forms - mostly in the dairy sector - it is not common. For young farmers contract farming is far more suitable than leasing as it allows them to match the production risk faced with their financial resources.

This contract farming model is a relatively new option for land tenure. It has been widely adopted in the UK and originated in the New Zealand Dairy industry. The Savill’s Global Farmland Index shows that NZ farm land values are even higher than those in the UK and this has driven innovation in rural land tenure. In the UK, the use of contract farming is taking over from share-farming as an alternative to leasing.

The Contract Farming Agreement (CFA) is relatively simple and aims to avoid many of the complexities of a share-farming model or partnership. It is an agreement between a landowner or tenant who is referred to as the ‘Farmer’ and a contract farmer who is referred to as ‘The Contractor’.

The two parties to the CFA run their own separate business with their own bank accounts, and tax administration. The CFAs are often for cropping, but can include livestock. It is an excellent way for two businesses to manage risk and return in an agricultural enterprise in a more formal manner than the traditional share-farming agreement. A key benefit in the Australian context is that both would be primary producers for tax purposes.

The Contractor’s basic remuneration is set at a level at which they will make a small profit to incentivise them to produce as large a divisible surplus as possible (as the Contractor will receive most of it). The Farmer receives a small profit if conditions allow with much lower risk. There are a huge number of variations in the manner the divisible surplus is split.

The benefits of the contract farming model

- The farmer, by employing a contractor, continues to trade in their own right (which allows them to continue as a farmer for tax, etc.).

- Can be used by an existing farmer to expand their farm business and improve economies of scale.

- Useful for farmers wanting to reduce the capital they have tied up in machinery or to reduce their physical farm workload.

- Effective structure for an investor looking for involvement in agriculture (with associated tax advantages of land ownership), but who do not have farming experience.

- Can provide an entry point for new/young farmers (as the Contractor) and risk can be dialled up or down depending on the new farmers financial resources.

- The split for the divisible surplus can also be used to apportion losses and thus share the risk of the enterprise.

- Allows a new farm enterprise to be taken on/added to existing holdings without having to purchase land or find a lease.

- A new enterprise can focus on working capital instead of the capital costs of buying land.

- Simple to understand, easy to operate and inexpensive to administer.

- Is applicable for cropping, mixed farming, livestock operations, fruit and intensive farming, and also low intensity grazing (such as hill-farming in the UK and pastoral leases in Australia).

A transition model

Another option for Australia would be to combine a number of these agreements to secure the engagement of a young farmer to work in a farm business and develop their own operation.

- The transition model using various forms of land tenure would assist young farmers.

- The young/new farmer will benefit if they can gain exposure at an early stage to a share of profit, without exposing themselves to all of the risk of a farm business (Canadian employment model of contract farming agreement)

- As they achieve success, they can transition to a model that provides a greater share of the rewards as their improving financial strength allows them to shoulder a greater share of the risk

- Eventually a lease would provide risk-free return for the landowner and total control of the farm business to the tenant

- An agreement to move through forms of land tenure in a progression can work for both parties

- The key issue will be finding the land/landowner willing to undertake these ventures.

Managing the transition to a lease and retiring creates a range of opportunities

While attention is often focused on attracting young farmers to the industry, the key issue for many is access to farm land. Meanwhile, many older farmers cannot afford to retire or have not found a solution to their succession issues and do not want to sell their land.

Leasing can solve both issues. Retiring farmers can retain the farm land, remain in their homes, and generate and income. Planning is required for the retiring farmer to determine how this plan will develop and how much income they will require. The release of additional lease land onto the market then creates opportunities for young or new farmers to establish farm businesses or existing farmers to expand.

Reasons to retain farmland

- It has a competitive record as an asset class

- The farmer can retire in place and retain their connection to their land

- They can use land tenure models to manage their exit from farming:

- to suit their desired workload

- pass on knowledge of farming in the region

- to manage tax issues created when they cease to be a primary producer. (Share-farming a portion of their farm rather than leasing it all out allows farmers to retain their primary producer status - this arrangement can be maintained until all livestock sales have been made and farm management deposits (FMDs) have been brought into annual income, and then the share-farm land can be included in the lease of the larger area).

Key considerations for retiring farmers

- Succession planning - are any family members interested? If not, there is greater flexibility to consider the options.

- What is their current asset mix? Do they have off-farm assets? How diversified is their portfolio of assets? What is their debt level?

- Where to live?

- What income is required? How can they generate this income with a level of risk they are comfortable with (diversification)?

Retirement income required

Most of these factors will relate to the circumstances of the farm business, but we can use the Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (AFSA) retirement standard to indicate the income required. The ASFA retirement income required in September 2015 for a ‘comfortable retirement’ (which assumes you own your own home) is $58,915 per annum.

Managing the transition – leasing and share-farming

A retiring farmer can lease their land and generate an income from the land with reduced production risk while retaining all of the benefits of owning farm land. This also allows them to sell down the working capital they have built up and use the funds to reduce debt or invest off-farm.

The lease can be combined with a share-farming agreement on part of the land, with the tenant allowing the retiring farmer to manage their exit from farming and the tax issues that are often created.

Opportunities created

While the use of the land tenure models can solve issues for the landowners it also creates opportunities for other farmers:

- Young farmers can use leasing, share-farming or contract farming to establish a farm business and gain expertise

- Existing farmers making profits from their farm business can expand their operations and improve their economies of scale

- Use leasing more widely in conjunction with share-farming if ready to retire and consider contract farming if it fits with succession planning and the farmer is looking for reduced risk and a longer period to retirement

Recommended models - case studies

In these case studies we have assumed that the farm couple are looking to retire in manner that fits the ‘comfortable’ ASFA definition and will live in their own home. This home will most likely continue to be the farm house. This assumption means they need to generate a retirement income of approximately $59,000.

Recommended model case study 1 – leasing and share-farming

The start point is a traditional farm business on 1000 acres of owned land with an investment in working capital and some off-farm investments. The owner is looking to retire and has no family members wanting to take over the farm, but they do not want to leave the farmhouse.

| Farm | $'000 | Farm profit | Gross margins ($/acre) | Area | $'000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land (1000 acres @ $2000/acre) | 2000 | Crop | 194 | 800 | 155 |

| Sheep | 160 | Sheep | 206 | 200 | 41 |

| Machinery | 150 | Total gross margins | 197 | ||

| FMDs | 200 | less | |||

| Total farm assets | 2510 | Interest | 24 | ||

| Non-farm assets | Overheads | 30 | |||

| Shares | 21 | Total overheads |

54 |

||

| SMSF | 480 | Profit |

143 | ||

| Total non-farm assets | 501 | Return on farm assets (%) | 5.68% | ||

| Total assets | 3011 | Non-farm income |

@ 5.6% |

28 |

|

| Liabilities | Total income |

171 |

|||

| Overdraft | 15 | Overall return on assets |

5.67% |

||

| Bank Term Debt | 355 | ||||

| Machinery Finance | 30 | ||||

| Total liabilities | 400 | ||||

| Net worth | 2611 | ||||

| Equity | 87% | ||||

If the farmer was to sell up they would have to create a diversified asset portfolio from the land sale proceeds and pay tax on the sale of livestock and the FMDs in the one year, as well as addressing the capital gains tax issues.

An alternative is to lease, but in this situation they would lose their primary producer status and have the same tax issues with regards to the livestock and FMDs. In order to maintain their primary producer status, they can share-farm some of the land with the tenant leasing the main area of the farm.

This reduces the landowner’s production risk and creates income that has less exposure to the production risk of the business.

Several years later

After a number of years (however long it takes to solve the tax issues related to selling down sheep and withdrawing the FMDs) the farm business has been transformed. Working capital investments have been sold, FMDs withdrawn, debt repaid and off-farm investments increased.

| Farm | $'000 | Farm profit | $/acre | Area | $'000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land (1000 acres @ $2000/acre) | 2,000 | Lease income |

$95/ac. |

800 |

76 |

| Sheep | 0 | Share-farming |

75/25 split |

200 |

40 |

| Machinery | 0 | Total farm income |

116 |

||

| FMDS | 0 | less |

|||

| Total farm assets | 2,000 | Overheads |

10 |

||

| Non-farm assets | Total overheads |

10 |

|||

| Shares | 21 | Profit |

106 |

||

| SMSF | 590 | Return on farm assets | 5.30% |

||

| Total non-farm assets | 611 | Non-farm income |

5.6% |

34 | |

| Total assets | 2,611 | Total income |

140 |

||

| Liabilities | Overall return on assets |

5.37% |

|||

| Overdraft | 0 | ||||

| Bank term debt | 0 | ||||

| Machinery finance | 0 | ||||

| Total liabilities | 0 | ||||

| Net worth | 2,611 | ||||

| Equity | 100% | ||||

At some stage the share-farming agreement can be terminated and the land leased out in its entirety.

Returns

The return on the farm assets and overall assets does not include the return on the farm land asset. It shows that the leasing model has a slightly lower overall return on assets than the owner farming the land, however it carries much less production risk (just the share-farming area). When the share-farming agreement has served its purpose and tax issues are resolved, all production risk can be removed by leasing the whole land area out. However, some farmers choose to retain the share-farming agreement in this form to maintain some exposure to the upside of a good outcome!

Recommended model case study 2 – contract farming

This model shows how a contract farming agreement would work between the landowner ‘Farmer’ and another farmer undertaking much of the work, the ‘Contractor’.

| 1000 acre Australian example - farming contract (625mm rainfall) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Output | Area (ha) | Yield (t/ha) | $/tonne | $ | $ |

| Wheat | 202 | 4.5 | 250 | 227,250 | |

| Canola | 101 | 1.5 | 550 | 83,325 | |

| Barley | 101 | 4.5 | 220 | 99,990 | |

| Total income | 404 | 410,565 | |||

| Variable costs* | $/ha | ||||

| Wheat | 202 | 263 | 53,126 | ||

| Canola | 101 | 334 | 33,734 | ||

| Barley | 101 | 263 | 26,563 | ||

| Total variable cost | 113,423 | ||||

| Gross margin | 297,142 | ||||

| Contractor costs | $/ha | ||||

| Contractors basic remuneration ($/ha) | 220 | 88,880 | |||

| Overheads (agreed fixed costs - on this area only) | |||||

| Labour | 0 | 0 | |||

| Fuel & vehicle | 5 | 2,020 | |||

| Insurance | 9 | 3,636 | |||

| R/M Ind | 5 | 2,020 | |||

| Admin | 5 | 2,020 | |||

| Rates & rent | 12 | 4,848 | |||

| Interest (on working capital) | 22 | 8,888 | |||

| Sundry | 7 | 2,828 | |||

| Total overheads | 115,140 | ||||

| Net return | 182,002 | ||||

| Farmers basic return ($/ha) | 200 | 80,800 | |||

| Divisible return | 101,202 | ||||

| Farmer | 50% | 50,601 | |||

| Contractor | 50% | 50,601 | |||

| Total return | $/ha | $/ac | |||

| Farmer | 325 | 132 | 131,401 | ||

| Contractor | 345 | 140 | 139,481 | ||

The return is lower for the ‘Farmer’ than if they had farmed the land on their own, but they have not had to do as much work (the equivalent to having all work done by Contractors) and they have shared the risk of the cropping season.

| *Variable Costs | Wheat | Canola | Barley |

|---|---|---|---|

| ($) | ($) | ($) | |

| Seed | 22 | 33 | 22 |

| Chemicals | 57 | 69 | 57 |

| Contract services (paid for in the Contractor's basic remuneration) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fertiliser & soil conditioners | 128 | 177 | 128 |

| Freight/cartage | 18 | 17 | 18 |

| Repairs & maintenance | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| Fuel | 20 | 22 | 20 |

| Insurance | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Sundry | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| Total | 263 | 334 | 263 |

Outcomes for the farmer

- The forecast return for the Farmer (land-owner or tenant) from the Contract Farming Agreement is $131,401.

- If the farmer had leased the land out they would have received approximately $85-$100 per acre, which is between $85,000 and $100,000. The farmer’s basic return under this agreement is $80,800, but this is after overheads relating to the property are deducted, making it quite comparable to the lease income.

Outcomes for the contractor

- The forecast return for the contractor from the Contract Farming Agreement is $139,481. The contractor has accepted a lower return than if they were leasing the land and operating it themselves. However, they also share the financial risk of a negative outcome.

- The contractor’s basic return is set about the level that a contractor would earn to perform all of the inputs for the crop ($190-$210 per hectare). The divisible surplus then creates an incentive for the Contractor to produce the best outcome possible.

- The Contract Farming Agreement may also be the lure the contractor needs to convince the farmer to enter an agreement when a lease does not meet the needs of the farmer.

In the event of a loss

- Contract farming allows the potential of a good harvest to be shared, but also shares the risk of a poor cropping outcome.

- In the event of a poor season the divisible surplus would be reduced and if there was insufficient income to cover the contractor’s basic remuneration and the farmer’s basic return then the two parties would share liability for the working capital facility debt in the same proportion as their agreed share of the divisible return (e.g. 50/50).

Conclusion

- Any farm business that has not been able to consistently generate more profit than they would have received from leasing their land must consider their land tenure options. Many farm businesses would be better off leasing their farms out.

- Farmland values have appreciated steadily over the long-term and compare favourably with long-term returns from other asset classes since the impact of the GFC, particularly when farm income (return from working capital) is included.

- The current economic conditions have reduced the incentives for retiring farmers to sell farmland and invest in a diversified portfolio of other asset classes due to the absence of compelling opportunities.

- Contract farming agreements allow a landowner to continue farming with a reduced risk and workload. They also allow another farmer to get started or expand and get exposure to a good harvest while also managing their risk.

- For young farmers contract farming is far more suitable than leasing as it allows them to match the production risk faced with their financial resources.

- Leasing (with a small area of share-farming to manage the issues created by ceasing to be a primary producer) can allow a retiring farmer to retain their land asset, generate an income and retire in place; all while creating opportunities for other farmers to expand or establish new businesses.

Useful resources

- A guide to compare the returns from the following tactics:

- Sell farm and invest proceeds

- Lease the farm

- Sharefarm the farm

- Checklist for the retiring farmer

- Checklist for the expanding farmer.

Contact details

Duncan AshbyRG Ashby & Co Pty Ltd

96 Yarra Street

PO Box 916, Geelong VIC 3220

03 5224 2663

0430 505 615

duncan@ashbyconsulting.com.au

Ashby Consulting

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK