Management of the major mungbean diseases in Australia

Author: Lisa Kelly, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Toowoomba, Qld | Date: 21 Jun 2016

Take home message

- For management of halo blight and tan spot: Plant seed with the lowest possible levels of infection, use varieties with higher levels of resistance, clean harvesting equipment, control weeds and volunteers, and use suitable crop rotations.

- For management of fusarium wilt: Avoid paddocks previously affected by the disease, plant seed into well-drained soils, and avoid plant stress

Introduction

With an increase in mungbean production in recent years, there has also been an increase in reported diseases. Disease surveys and samples submitted for diagnosis have revealed an increase in many diseases across a number of crops, particularly those pathogens that survive in stubble.

Halo blight has been the major issue for mungbean growers in southern Qld in the last two years, presumably due to the cooler, wet start to the growing seasons. These weather conditions are less favourable for tan spot which has been less of an issue for most growers across the northern region during this time, although the disease remains a concern when sourcing disease-free seed. Fusarium wilt is becoming an increasing threat to growers, with some paddocks having as many as 80% of plants affected by the disease. Further research is vital to better understand these diseases and will aid in the development of future integrated disease management strategies.

Halo blight

Halo blight, caused by the bacterium Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. phaseolicola, has become a significant issue to growers across the northern region in recent years. On younger leaves, halo blight is characterised by small, water-soaked lesions that are surrounded by a yellow-green halo. Symptoms are often visible at the 1st or 2nd trifoliate leaf stage and are often the result of seed borne infection. Infected seedlings typically survive and become the major source of inoculum for later infection in the crop. Older lesions have less pronounced haloes and lesions often coalesce to produce larger necrotic regions. Lesions are visible on both sides of leaves. Circular brown or red water-soaked lesions may develop on pods, with clumps of bacteria often oozing from the lesions and often forming a crusty drop. Often seed directly below pod lesions will be internally infected with halo blight, whilst the surrounding seed often become externally infected as they come into contact with the bacteria or infected plant tissue.

The bacterium is spread from infected plant tissue to healthy plants by water droplets from rainfall or overhead irrigation, and contact between adjacent wet leaves. The bacterium invades plant tissue via wounds and natural plant openings during periods of high humidity, and can survive on the surface of both resistant and susceptible plants, even when there are no obvious symptoms of the disease. Under ideal environmental conditions symptoms appear on plants 7-10 days after infection. Temperatures of 18-23ºC have been recorded as optimal for the development of the disease.

Multiple putative pathotypes

Outside of Australia numerous pathogenic races of halo blight have been identified in beans based on differential host reactions. A few years ago the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) mungbean pathology team identified two separate putative pathotypes (Pt). One of those putative pathotypes has the capacity to overcome the improved sources of resistance recognised in the National Mungbean Improvement Program (NMIP). About 350 halo blight isolates have been collected from breeding trials and growers’ paddocks across the northern region since July 2013. Most isolates have been collected from southern Qld, where the disease has been more prominent in recent years. A differential set of six mungbean genotypes, consisting of both commercial cultivars and advanced breeding lines are being used as a differential set to identify halo blight pathotypes diversity. From 80 halo blight isolates, 12 putative pathotypes have been identified, with pathotypes 1, 2 and 4 occurring more frequently (Table 1). At least six of these putative pathotypes were virulent on lines (M773 and OAEM58-62) previously resistant or immune to halo blight isolates prior to 2012, and which have been used extensively in the mungbean breeding program as sources of resistance. Table 1 details the mungbean genotypes and the differentiation of the halo blight pathotypes. Further screening of halo blight isolates will be conducted to confirm this diversity of pathotypes and determine whether the dominant pathotypes (1, 2 and 4 shown in Table 1) are the same in all regions. The findings from this research will lead to investigations into any genetic differences between the identified pathotypes and the genetics of resistance.

Table 1. Identification of putative pathotypes (Pt) in halo blight (Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. phaseolicola) isolates from mungbean (Y = inoculated plants displayed symptoms; N = no symptoms)

|

Genotype |

Pt 1 |

Pt 2 |

Pt 3 |

Pt 4 |

Pt 5 |

Pt 6 |

Pt 7 |

Pt 8 |

Pt 9 |

Pt 10 |

Pt 11 |

Pt 12 |

|

AusTRC 321818 |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

|

M773 |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

|

OAEM58-62 |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

|

ATF2074 |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

|

AusTRC 324872 |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

|

Crystal |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

|

Frequency isolated (%) (n=81) |

9.9 |

40.7 |

2.5 |

23.5 |

6.2 |

4.9 |

1.2 |

4.9 |

2.5 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

Tan spot

Tan spot (also known as bacterial scorch and wilt) is caused by the bacterium, Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens pv. flaccumfaciens. Symptoms in seedlings, often resulting from seed borne inoculum, can be seen on the 1st or 2nd leaf trifoliate when large chlorotic areas develop on leaves. As the seedlings grow, they often wilt and die rapidly. Surviving seedlings are often stunted and are the major sources of inoculum for later infection in the crop. Leaves on older plants develop a scorched appearance, with interveinal necrotic lesions surrounded by a distinct chlorotic margin. The scorching gradually expands towards the midrib and may eventually cover the entire leaf. Affected lesions become tan in colour and may disintegrate during high winds, giving the leaves a ragged appearance. The disease can result in death of florets, and small pods may abort or remain stunted. The bacterium is thought to be systemic within plants and can infect seeds.

It is thought that the bacterial cells enter plants through the vascular system from infected seeds, or though wounds on aboveground plant parts. Unlike halo blight, tan spot is not easily spread in rain or through contact with wet foliage, and is thought to be able to infect tissues in the absence of rain. The disease is favoured by high temperatures (>30º) and plant stress. Storms with high winds, rain, and hail that wounds plants provide the perfect opportunity for tan spot to become established and transfer from infected plant tissue to healthy plants.

Breeding for disease resistance

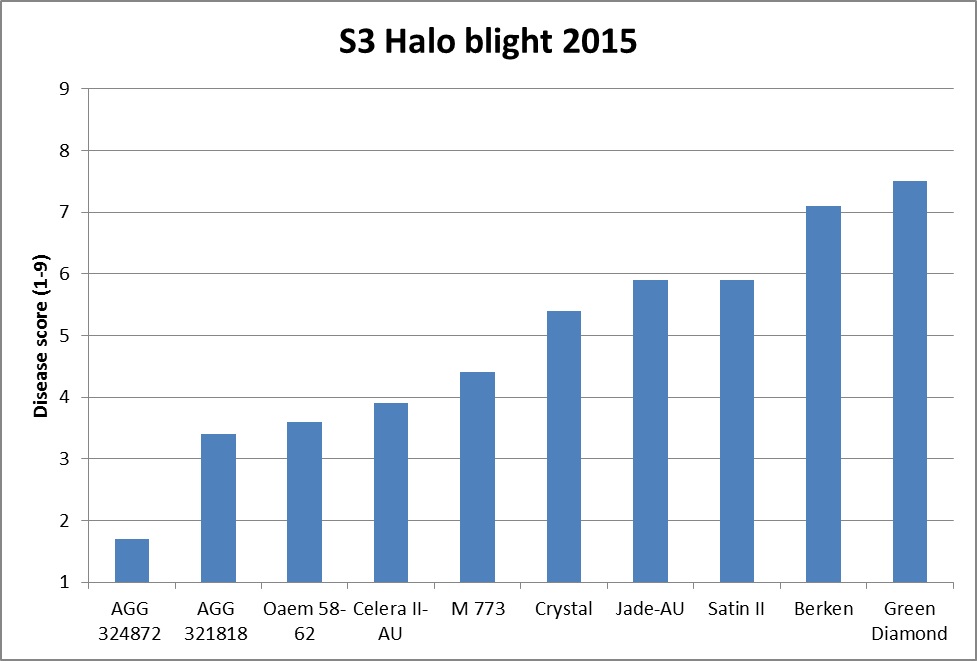

As part of the NMIP advanced breeding germplasm is screened in both field disease nurseries and in glasshouse trials to determine their relative levels of resistance to the two bacterial diseases. Plants are scored for disease resistance using a 1-9 scale close to maturity. Disease screening within the NMIP has identified sources with major genes of resistance to halo blight and improved resistance to tan spot and has incorporated those into their breeding program. Figure 1 demonstrates the improved sources of resistance in a few advanced breeding lines to the halo blight pathogen from a field trial in 2015 at the DAF Hermitage Research Facility. Although improved sources of resistance have been identified for halo blight, current breeding efforts have become more difficult with the recent identification of multiple pathotypes that may overcome this resistance. Further research is needed to investigate the genetics of resistance to both halo blight and tan spot.

Figure 1. Relative resistance of the mungbean commercial cultivars and advanced breeding lines to halo blight in the 2015 halo blight disease nursery at the DAF Hermitage Research Facility. Disease is scored on a 1-9 scale, where 1 = no disease and 9 = high levels of disease.

Management of the two bacterial diseases

There are currently no registered chemicals for the control of halo blight and tan spot on infected plants or seed.

The risk of a halo blight and/or tan spot epidemic occurring in a crop can be minimised by:

- Selecting resistant varieties

The variety Celera II-AU provides the best levels of resistance to the halo blight pathogen, rated as Moderately Resistant. All other commercial varieties are either susceptible or moderately susceptible to both tan spot and halo blight, although Jade-AUand Crystal have the next best levels of resistance.

- Using low risk planting seed

Infected seed is thought to be the major source of infection within a crop. Only one halo blight infected seed per 10,000 is enough to produce an epidemic under ideal environmental conditions. Avoid using seed from an infected mungbean crop. Australian Mungbean Association (AMA) approved seed is sourced from crops inspected for disease symptoms during the growing season.

- Crop rotation

The following crops and pasture plants are potential hosts for one or both of the bacterial diseases; French bean, navybean, lima bean, cowpea, adzuki bean, soybean, pigeon pea, guar, faba bean, siratro, native glycine, kudzu, and lablab. Mungbean should be rotated with a non-host crop for at least two years to provide sufficient time for residue decomposition. Burying stubble will also assist in this process.

- Control host weeds and volunteers

Volunteer plants and weeds such as cowvine, bellvine, morning glory, Desmodium and Centrosema are known hosts of one or both diseases and should be managed effectively.

- Restrict movement through the crop

Movement should be restricted through the crop to avoid wounding the foliage and spreading the pathogen further. Harvesting equipment should be thoroughly cleaned of mungbean residues, preferably with an antibacterial solution, to avoid spreading the bacterial cells from infested residues to the surface of seed during harvest.

Fusarium wilt

Fusarium wilt is becoming an increasing problem to mungbean growers across the northern region. The disease is usually found at a low incidence (1-10%) in most paddocks, although in recent years it has caused extensive damage to several paddocks (greater than 70% incidence).

Fusarium wilt often occurs in paddocks experiencing stressful conditions, such as excess water. Heavy clay soils are more often affected, particularly on the edge of paddocks and in low lying areas. Both seedlings and older plants can be affected by the disease. Affected seedlings wilt and their lower roots rot and may develop a basal rot on stems. If infection occurs in older plants, the leaves wilt and the xylem tissue becomes discoloured.

Little is currently known of the disease in Australia, including which species are responsible. Isolations from affected plants across the northern region have consistently isolated two Fusarium species; F. oxysporum and F. solani. Both species have been isolated from approximately 80% of plants affected with the disease, as seen in Table 2. Both species have been associated with the disease in mungbean and other bean or Vigna species outside of Australia. Preliminary glasshouse trials suggest both species are involved, although further research is required to confirm this. Future research plans to investigate the relative levels of resistance to the pathogen/s in the current commercial varieties and advanced breeding lines; alternative hosts; and other integrated disease management strategies.

Table 2. Relative abundance of Fusarium species isolated from mungbean plants with fusarium wilt

|

Fusarium species |

Frequency isolated (%) (n=61)a |

|

F. solani |

39.3a |

|

F. oxysporum |

39.3a |

|

F. moniliforme species complex |

9.8b |

|

F. incarnatum-equisetti species complex |

8.2b |

|

F. proliferatum |

3.3b |

aValues followed by a common letter are not significantly different (P>0.05)

Management of fusarium wilt

It is recommended that growers avoid planting mungbean into paddocks previously affected with fusarium wilt for a number of years. Ideally seed should be sown into well-drained soils that has been optimally fertilised and avoid stress, such as excess water.

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support.

Contact details

Lisa Kelly

Plant Pathologist

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries

203 Tor St, Toowoomba Qld 4350

Ph: 0477 747 040

Email: lisa.kelly@daf.qld.gov.au

Varieties displaying this symbol beside them are protected under the Plant Breeders Rights Act 1994.

GRDC Project Code: DAQ00186,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK