Learnings from seven years of grazing crops research in Western Australia

Author: Philip Barrett-Lennard | Date: 23 May 2019

Key messages

- Whole farm profit can be improved with crop grazing, and is likely when there is a higher farm stocking rate, some crops are early sown, crops are grazed with highly responsive livestock, and yield penalties are kept to a minimum.

- Crops offer significant benefits to livestock due to very high feed quality and feed availability.

- In most cases, crop grazing does reduce grain yield.

- Early and light grazing reduces the size of grain yield penalties when crop grazing.

Aims

Over the last decade, mixed farmers in Western Australia have increasingly embraced crop grazing as a tool to improve livestock productivity and whole farm profitability. However, much of the information on crop grazing was initially based on research and experience from New South Wales and Victoria.

The aim of this research was to quantify the impact that crop grazing in Western Australia has on whole farm profit as a result of changes to grain yield and quality, crop flowering date and frost damage and livestock productivity.

Method

A series of grazing crops trials was conducted across Western Australian between 2010 and 2016 as part of the GRDC funded Grain & Graze 2 and Grain & Graze 3 projects. This paper summarizes the key learnings from this and other relevant research on the topic of grazing crops.

Results

1. Whole farm profit can be improved, but…

Whole farm economic modelling conducted by Bathgate and Young (2015) and Creelman (unpublished) indicates that crop grazing can improve whole farm profits, but this is not universally true, and in many cases simply swaps crop income for livestock income. The keys to improving whole farm profits through crop grazing are to run a higher livestock stocking rate, sow crops early to provide crop biomass for grazing in late autumn and early winter when pasture is scarce, minimise grain yield penalties from overgrazing, and to graze crops with an economically responsive class of livestock. If these farming system changes are not implemented along with crop grazing, whole farm profit is likely to remain unchanged or even decline, as too much crop income is sacrificed in the chase for additional livestock income.

While only anecdotal, case studies of WA mixed farmers who have adopted crop grazing suggest a very similar story.

Table 1: The change in farm profit ($) and area of crop grazed (ha) at different yield penalties for two levels of dry matter removed (kg/ha) when grazing crops on the South Coast (from Bathgate and Young, 2014).

Yield Penalty | 0% | 5% | 10% | 15% | 20% | 25% | 30% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Profit @ 300kg/ha ($) | +25,000 | +6,300 | +3,800 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Area @ 300kg/ha (ha) | 1,100 | 106 | 106 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Profit @ 1000kg/ha ($) | +34,200 | +22,100 | +11,500 | +6,500 | +5,800 | +5,200 | +4,600 |

Area @ 1000kg/ha (ha) | 1,100 | 500 | 479 | 478 | 478 | 467 | 278 |

2. Crops offer significant benefits to livestock

Crops offer significant benefits to livestock in two ways. The first is superior feed quality, with Grain & Graze trial data showing that cereal crops consistently have higher metabolisable energy and crude protein than annual pastures in early winter. With ME levels consistently in the 12 to 14 MJ/kg range, very high animal production levels can be achieved. This compares to the 9 to 11 MJ/kg we have measured in annual pastures. The second is high animal intake at low feed-on-offer (FOO) levels. Cereal crops, with their very upright growth habit, allow animals to consume significantly more feed at low FOO levels when compared to prostrate annual pastures such as clover and capeweed.

High intake of a high quality diet leads to very high levels of animal production. In Grain & Graze trials near Moora, pregnant twin bearing ewes consistently gained body condition score while grazing cereal crops in June, while the body condition score of twin bearing ewes grazing pasture often declined.

Table 2: Ewe condition score (CS), feed on offer (FOO in kg/ha), metabolisable energy (ME in MJ/kg) and crude protein (CP in %) of pasture and crop, at the start (in) and end (out) of a 3 week trial at “Cranmore”, east of Moora, in June 2016.

CS in | CS out | FOO in | FOO out | ME in | ME out | CP in | CP out | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Crop | 3.1 | 3.4 | 77 | 277 | 12.2 | 12.5 | 38.5 | 36.8 |

Pasture | 3.1 | 3.0 | 1140 | 852 | 9.8 | 7.1 | 13.4 | 19.0 |

3. In most cases, grazing reduces crop yield

A large number of crop grazing trials have been conducted across WA. In most cases, grazing reduces crop yield. Occasionally yield is improved by grazed, and when this occurs, it is often where a delay in flowering has helped the crop to avoid a frost event. The size of any reduction in crop yield is largely governed by the timing and intensity of grazing (see Key Finding 7 below), but also by the interaction between grazing and other environmental stresses such as heat, moisture stress or waterlogging. Research by Seymour et al (2015) and Barrett-Lennard et al (2013) shows a very clear trend where the earlier and lighter crops are grazed, the lower the negative impact on crop yield.

When crop grazing is managed appropriately, yield reductions in the 0 to 10% range should be expected. To improve whole farm profit, the aim is to more than offset the lost income from these small yield reductions with an increase in profitability of the livestock enterprise.

4. Sowing early significantly improves early biomass for grazing

Sowing crops destined for grazing early has a huge impact on the amount of biomass available for grazing in late autumn and early winter. In most seasons, mixed farms in Western Australia suffer from a feed shortage in late autumn and early winter. Supplementary feed, in the form of grain and hay, is typically used to fill this feed shortage. Early sown crops potentially offer a cost and labour effective alternative.

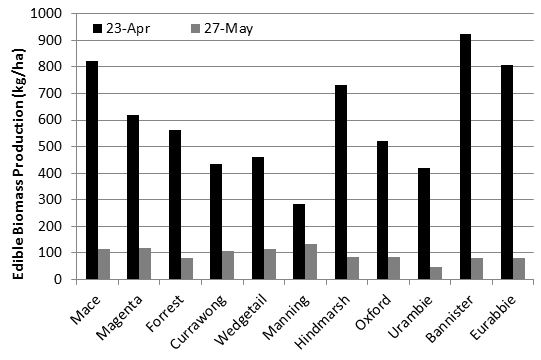

In Grain & Graze trials at Wickepin in 2014 and 2016, crops sown in mid-late April produced significantly more early winter biomass than late May sown crops. Late May sown crops only produced 50 to 200kg/ha of edible biomass by early to mid-July, while April sown crops produced 400 to 2200kg/ha of edible biomass by early-mid July, with approximately 50% of that being available by early June.

Figure 1: Edible Biomass Production (kg/ha >5cm) up to mid-July from an early (April 23) and late (May 27) sowing at Wickepin in 2014 (from Barrett-Lennard et al, 2015).

5. Variety does and doesn’t matter

All crops can be grazed. The so-called “dual purpose” varieties are winter types with a vernalisation requirement for flowering, and can be sown very early. Wedgetail Wheat is probably the best known example of a “dual purpose” variety.

Western Australia has fewer early sowing opportunities than southern NSW, the home of Wedgetail, so the vast majority of crop grazing is conducted on standard “grain only” spring type crop varieties. Wheat, barley, oats and canola are all suitable and used for grazing in WA. In reality, everything is “dual purpose” and variety doesn’t matter.

However, when sowing very early to chase extra grazing biomass in late autumn and early winter, variety does matter. Growers wanting to sow cereals in March and early April do need to plant winter types with a vernalisation requirement for flowering. This is because our standard spring varieties will develop prematurely in response to the warmth and photoperiod of autumn. Some winter varieties currently being sown in this window by WA growers include Urambie barley (a winter feed barley), Currawong wheat (a winter feed wheat grown), Wedgetail wheat (a milling winter wheat) and Revenue wheat (a winter feed wheat). Urambie barley is by far the most popular of these varieties, with a number of growers in Esperance using it in their program. A combination of early vigour and early maturity is the main reason for its popularity. The problem with all the currently available winter wheats is their flowering date is too late for the vast majority of the Western Australian grain belt. What is needed is a fast maturing winter wheat variety, which can be sown early but will still flower at a similar time to spring cereal varieties sown in May. AGT will hopefully release RAC2341, a fast maturing winter milling wheat, in 2018 to fill this gap. It has the potential to be a game changer for farmers wanting to sow early and graze.

Canola is somewhat similar to cereals in that both spring and winter types exist, and the currently available winter types are very late flowering. Further breeding and development is required to find suitable winter canola varieties suitable for WA. A small number of growers in the Great Southern and South Coast are experimenting with the currently available winter canola varieties. The vernalisation requirement for flowering means that it can be sown in spring, summer or early autumn. A spring sowing, as used by a number of Victorian mixed farmers, can provide up to 6 months of grazing over summer and autumn if conditions are favourable.

6. Grazing crops delays their flowering

Grazing a crop delays its flowering date. Research by Curtin and Whisson (2014) suggested a fairly simple “rule of thumb” applied, where every 2 days of grazing delayed flowering by 1 day. The data from Grain & Graze research, and observations made by farmers and agronomists, would suggest this rule of thumb is a useful guide, but by no means a universal truth.

Based on Grain & Graze trial data, our observations are that (a) earlier sown crops are delayed more by grazing than later sown crops, (b) spring type crops are delayed more by grazing than winter type crops, (c) heavily grazed crops are delayed more than lightly grazed crops, and (d) crops grazed during late tillering are delayed more than crops grazed during early tillering.

Table 3: The impact of variety, time of sowing, and grazing on flowering date (Z65 for wheat, Z45 for barley and oats) at Wickepin in 2014 (from Barrett-Lennard et al, 2015)

Time of Sowing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

23-Apr | 27-May | |||

Variety | Grazed | Ungrazed | Grazed | Ungrazed |

Wheat | ||||

Mace | 19-Sep | 28-Aug | 19-Sep | 19-Sep |

Magenta | 19-Sep | 29-Aug | 23-Sep | 23-Sep |

Forrest | 30-Sep | 19-Sep | 10-Oct | 9-Oct |

Currawong | 23-Sep | 19-Sep | 3-Oct | 3-Oct |

Wedgetail | 26-Sep | 19-Sep | 3-Oct | 3-Oct |

Manning | 17-Oct | 16-Oct | 24-Oct | 24-Oct |

Barley | ||||

Hindmarsh | 29-Aug | 11-Aug | 4-Sep | 2-Sep |

Oxford | 31-Aug | 19-Aug | 16-Sep | 11-Sep |

Urambie | 31-Aug | 26-Aug | 12-Sep | 11-Sep |

Oats | ||||

Bannister | 9-Sep | 22-Aug | 11-Sep | 10-Sep |

Eurabbie | 9-Sep | 5-Sep | 16-Sep | 16-Sep |

Average | 16-Sep | 5-Sep | 23-Sep | 22-Sep |

The impact that the delay in flowering from crop grazing has on grain yield is most likely to be variable. Clearly, if the delay pushes the flowering data away from a frost event, it could have a positive impact on yield. But if the delay pushes grain fill in to a period of hot and dry conditions, it could have a negative impact on yield.

Using grazing as a frost management tool is not recommended. When it comes to frost mitigation, altering crop type, variety and sowing time are proven and reliable, and don’t come with the risk of incurring a yield penalty from over grazing.

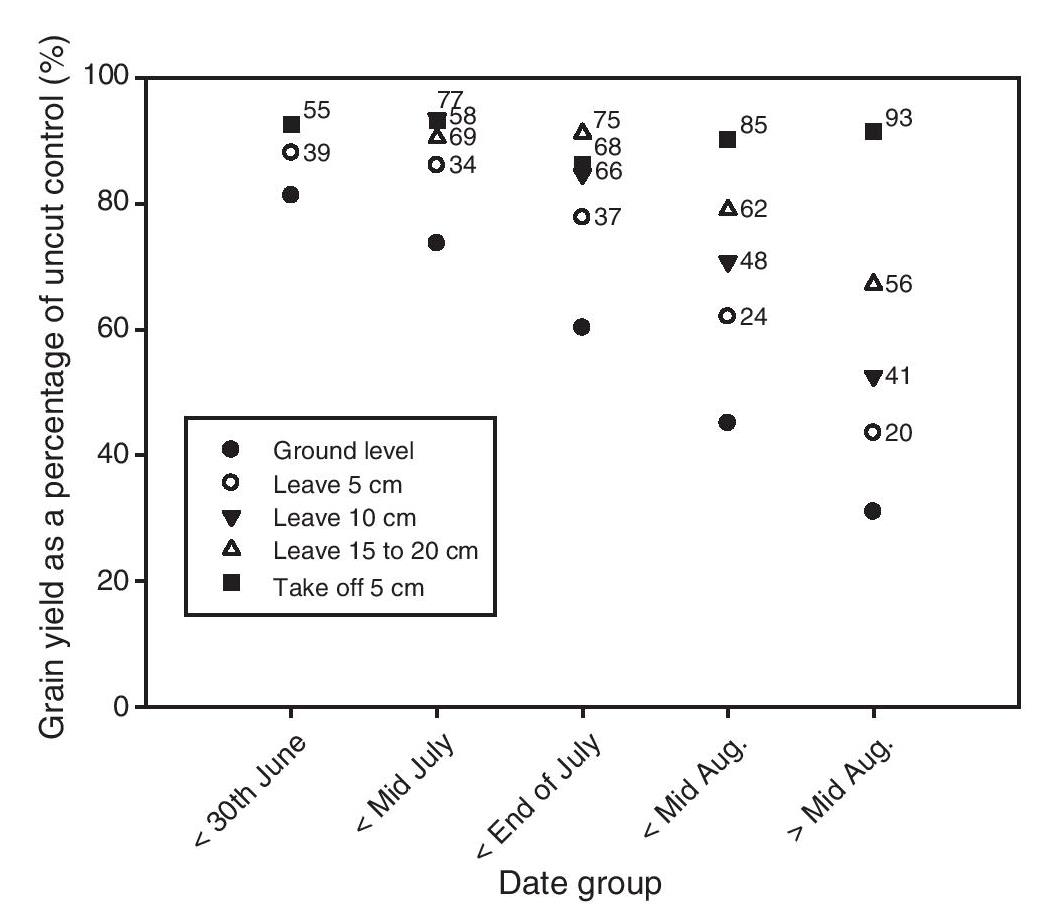

7. Graze earlier rather than later, and lighter rather than harder

Research conducted by Seymour et al (2015) shows that grazing crops lightly (“clip” grazing the top of the plant) and early in the growing season results in far smaller yield reductions than heavier and later grazing. Crash grazing (down to ground level) is not recommended based on both this data and farmer observations. Very light grazing during the early stages of stem elongation (July and August) can also result in only small yield reductions, although achieving this with livestock is not easy as they tend to graze paddocks unevenly.

Figure 2: The effect of the timing and intensity of crop grazing on subsequent cereal grain yield (from Seymour et al, 2015).

8. Don’t get hung up on stocking rate

There are many ways to graze crops. The initial thinking in WA was that a high stocking rate for a short period was preferable to avoid overgrazing and to speed up crop recovery. However we have found over time that due to low stock numbers and large paddock sizes, implementing more intensive grazing management on crops in WA is often not practical. The alternative is usually a low stocking rate over a longer period. This has proved to be very successful in the vast majority of cases. It reduces labour (shifting stock) and the need for temporary electric fencing (reducing paddock size). The only downside of a low stocking rate is that livestock will often unevenly graze a crop. If the grazing period is relatively short, say 2 or 3 weeks, the unevenness rarely causes too many problems. If the livestock do intensively graze (often by camping on) one small area of the crop, then crop yield is likely to be reduced a bit more in that area. Weeds may also proliferate on that small area due to the loss of crop competition.

One, perhaps rather extreme, example of using a low stocking rate over an extended period is the lambing of twin bearing ewes on crops. Deliberately very low stocking rates (1 to 2 ewes per hectare) have been used from early-July to mid-August, well beyond the normally recommended window for crop grazing. Due to the very low stocking rate, and the presence of un-arable land in the paddock (rocks, trees, creeks etc), sheep productivity was excellent and there was no impact on crop yield.

There are many ways to graze crops. Don’t get hung up on stocking rate.

9. Withholding Periods (WHP) can be challenging

Some pre and post emergent herbicides, seed treatments and many insecticides and fungicides have a withholding period from grazing after application. These can be as long as 15 weeks which can severely limit the grazing opportunity. As a result, the timing of grazing and spraying operations both need consideration when developing a crop grazing plan. In many cases, the application of post emergent herbicides and fungicides can be delayed until the end of grazing. But the long withholding periods of some pre-emergent herbicides (e.g. atrazine at 15 weeks in canola) and seed dressings (e.g. imidacloprid at 9 weeks in barley) can make crop grazing in certain situations all but impossible. And in case you are unaware, it is a legal requirement to observe withholding periods.

10. Grazing can exacerbate grass weed problems (pick your paddock)

Crop grazing can exacerbate grass weed problems because grazing removes some of the crop canopy, reducing competition between the crop and weeds. For this reason, grazing of crops that have a grass weed burden is not recommended. If the weed burden is very low, a short period of light “clip” grazing, where only the very top of the canopy is removed, will allow the crop to quickly recover from grazing and compete with weeds.

Table 4: The impact of crop grazing on weeds and ergot at Kojonup in 2014 (from Barrett-Lennard et al, 2015)

Grazed | Ungrazed | P-value | LSD (p=0.05) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Small Foreign Seeds (%) | 0.7 | 0.2 | <0.001 | 0.2 |

Ergot (cm) | 5.8 | 2.4 | 0.005 | 1.8 |

Conclusion

Recent research has greatly increased the knowledge and understanding of the economics and agronomics of crop grazing under Western Australian conditions. Growers should now be much more confident in their decision making when contemplating the adoption of crop grazing as a tool in their mixed farming business.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the contribution of Greg Warren, Michelle Handley, Sarah Hyde, Sheree Blechynden, Chloe Turner, Richard Quinlan, Geoff Fosbery, Ryan Pearce, Sam Taylor, Joe Young, Andrew Bathgate and John Young who worked collaboratively with the author on the GRDC funded Grain & Graze 2 and Grain & Graze 3 projects.

References

Barrett-Lennard et al (2013) Grazing crops in a dry year. Proceedings of the 2013 Perth Agribusiness Crop Updates.

Barrett-Lennard et al (2015) The impacts of early sowing and crop grazing on the grain yield and quality of a range of winter and spring cereal varieties. Proceedings of the 2015 Perth Agribusiness Crop Updates.

Bathgate and Young (2013) The economics of grazing crops in the Central Wheatbelt and South Coast regions of WA. Proceedings of the 2015 Perth Agribusiness Crop Updates.

Curtin and Whisson (2014) Delaying wheat flowering time through grazing to avoid frost damage. Proceedings of the 2014 Perth Agribusiness Crop Updates.

Seymour et al (2015) Effect of timing and height of defoliation on the grain yield of barley, wheat, oats and canola in Western Australia. Crop and Pasture Science.

GRDC Project Number FGI00010

Paper reviewed by Zoe Creelman and Greg Warren

GRDC Project Code: FGI00010,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK