Managing risk in mixed livestock and cropping systems

Author: Cam Nicholson, Nicon Rural Services | Date: 27 Feb 2018

Take home messages / call to action

- Managing risk is not about the middle or the average, it is the opposite. It is appreciating what happens at the extremes, the size or value of these extremes and how often they occur.

- Understanding the probability of different yield and price values occurring and if these values are correlated is essential in understanding risk.

- Usually diversification reduces risk (both downside but also upside risk).

Introduction

Risk is a natural and accepted part of farming. Australian agricultural production (based on value of output) is the most volatile in the world and the most volatile sector of the Australian economy (Keogh, 2013). This volatility conveys a level of risk that needs to be managed. Given most farmers are still operating despite two centuries of volatility, suggests they have developed long term strategies and operational tactics to cope with this ongoing challenge.

There are many strategies farmers use to manage production risk. Diversification in crop and pasture type, enterprise mix, targeting multiple markets and property location are common strategies. So is managing input costs, especially when production and prices can be highly variable.

Understanding risk

When we talk about risk, most of us immediately think about the negative consequences if an action goes bad. Dictionary definitions re-inforce this thinking. However this is only one aspect of risk. The word risk is derived from Italian word risicare, which means 'to dare'. To manage risk effectively we need to understand both the downside, or the potential harm from taking a risk and also the opportunities that taking a risk can offer.

There is no reward without risk. In farming, risk is a necessary part of making returns. Managing risk is about making decisions that trade some level of acceptable risk for some level of acceptable return for an acceptable amount of effort. Decisions can be made to reduce risk, but it usually comes at a price, namely lower returns.

A common definition of risk is likelihood by consequence. In other words, risk requires knowing how often an event happens (the frequency) and what is the impact (the value) when it does happen. A decision that increases risk will either increase the likelihood of an event happening and/or increase the consequence if it does occur. This increased consequence may be a greater return, not just a greater loss.

We must remember everyone has a different position on risk. Financial security, stage of life, health, family circumstances, business and personal goals can influence the amount of risk an individual is willing to take on. This position can change rapidly, sometime triggered by sudden events. Importantly no position is right or wrong, it is what the individual is comfortable living with.

Average values are commonly used in agricultural extension. We present average yields, average prices and average costs. While these averages convey a value (and are convenient), they rarely present the frequency of this average occurring. This would be fine if we consistently got these average values, but in agriculture we rarely do. The key drivers of profit in agriculture, namely yield, prices and some costs, have a range of values within and between production periods. If we use averages for analysis, it usually over estimates the profits and hides the volatility in those profits (Nicholson, 2013).

Understanding risk is not about the middle or the average, it is the opposite. It is appreciating what happens at the extremes, the size or value of these extremes and how often they occur. Managing risk is knowing what to do when these extremes occur, either by changing things to avoid them or having contingencies when they do occur.

Analysing risk

As described previously the derivation of risk is 'to dare'. This implies there is opportunity but it also implies a choice. As individuals we can influence how much risk we expose ourselves to by making choices.

Insights from the Grain and Graze program would suggest farmers mainly inform their decisions around risk based on past experience and intuition or instinct. Doing the ‘sums’ to understand the likelihood and consequence is much less common.

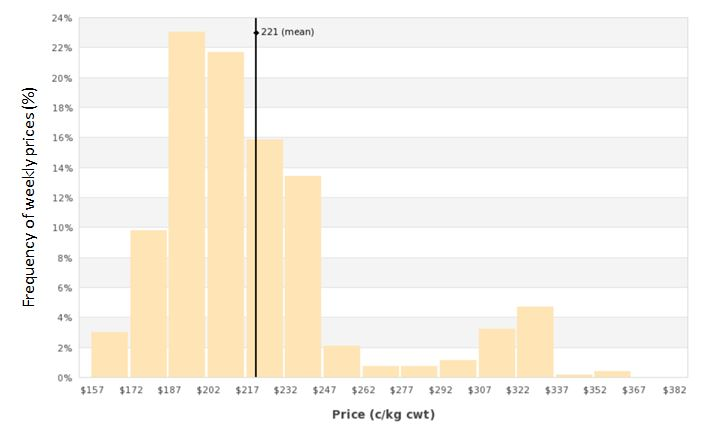

Through the Grain and Graze program we have developed a relatively simple way to put some numbers around the risk in a farming business. It is based on Excel with an additional program called @Risk by Palisade. Firstly the risky variables in a business are identified. These are inputs that we have little or no control over at the start of the season and are typically yields, prices and some costs. Graphs are created that show the amount or value of this risk and how often this amount or value occurs. It includes extreme and more common results and are referred to as distributions or frequency histograms. The broader the range in values the greater the volatility or risk (figure 1).

Figure 1. Example of the frequency of weekly prices for feeder steers in NSW from 1 Jan 2006 to 24 June 2016, inflated to June 2016 values (Ag Commodity Prices - Grain and Graze 3)

These ‘risky’ distributions are then substituted for the average values used in calculations. ;For example we may have used an average price for steers of $2.21/kg Lwt. By substituting this distribution, the program will do some calculations with a price around $2.21/kg, but also do calculations with prices at $1.90/kg, $2.50/kg and even $3.50/kg. However the frequency these prices occur will be different. There will be more calculations around $1.90/kg than around $2.50/kg and many more than around $3.50/kg.

The same can be done for yields (and some costs, although most costs increase in price but are not highly variable throughout the season). When the risky yield, price and cost values are combined, they reflect what happens in real life. For example, we may have a high yield but poor prices, so our gross income is about average. Less often we will have poor yields and poor prices and conversely we occasionally get high yields and high prices. Adjustments can also be made to link events such as often getting higher prices when yields are poor.

We create these distributions through a combination of historic information (‘form guides’) and gut feel. I call this ‘framing the odds’. Each distribution can be customised to suit your location, soil type, frost risk etc.

Not all risks are equal. The computer program enables a comparison between the risky variables. For example we might have a farm with 20 or so distributions but not all of these risks are of equal influence to our final profit. Some create more volatility than others and some are more influential in making or losing large amounts of money. We can identify these and examine the impact if we were able to change them. This scenario analysis is extremely valuable as it enables an understanding of the risk implications of large (and small) changes on the farming business before we make the changes.

Correlations

One reason for diversifying enterprises is to ‘decouple’ price and yield movements. We grow different commodities so if one fails to produce, a different crop or enterprise may still produce something. How strongly yields and prices are linked are referred to as correlations and understanding it is critical in managing risk.

Correlations (co- meaning ‘together’ + relation) can be calculated mathematically The numeric scale used for correlations is 0 to ±1 and is commonly referred to as the ‘r’ value[1] (or correlation co-efficient). If there is no connection or dependence between two variables, then it is considered a zero (0) correlation. If one variable exactly follows the size and direction of the fluctuations of the other it is positively correlated and given a value of one (+1). Conversely if one variable exactly follows the size and direction of the fluctuations of the other, but in opposite direction, it is negatively correlated and given a value of one (-1).

The r value can be broadly classified into ‘strengths’.

- Strong with r greater than ±0.8

- Medium with an r value between ±0.5 and ±0.8

- Weak with an r value less than ±0.5

- None with an r value of 0

Knowing a weak r value can be just as useful as knowing a strong r value because the weakness implies there is no connection between the two variables, so they should be considered independent of each other.

Price correlations for common crops and livestock enterprises is provided (tables 1 & 2).

Table 1. Correlation between common crops (July 2003 to June 2016)

Canola | APW wheat | Malt barley | Feed barley | Lentils | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Canola | 1 | ||||

APW wheat | 0.8 | 1 | |||

Malt barley | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1 | ||

Feed barley | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1 | |

Lentils | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1 |

Table 2. Correlation between sheep enterprises (July 2003 to June 2016)

18u | 24u | Trade lambs | Heavy lambs | Mutton | Live sheep | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

18u | 1 | |||||

24u | 0.5 | 1 | ||||

Trade lambs | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1 | |||

Heavy lambs | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1 | ||

Mutton | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1 | |

Live sheep | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1 |

Correlations can also be easily created between enterprises (Ag Commodity Prices - Grain and Graze 3).

Enterprise mix

Changing the enterprise mix, both in the type and scale of these enterprises changes the risk profile of a business. The following example is for a 1500 ha farm in the West Wimmera, but is based on a real farm. The key values are;

- 1,000 ha heavy soil, 500 ha light soil

- Typical enterprise mix: 40% wheat, 25% barley, 10% canola, 5% lentils, 5% bean, 15 % vetch hay.

- 1 manager, 0.5 labour

- Cost reduced by 20% if yield is decile 3 or less (less nitrogen use)

- Cost increased by 20% if yield decile 7 or more (greater nitrogen use)

- $0.5M debt, 6.5% interest

- $1.2M in plant and equipment (dep @10%)

In a second scenario the 500 ha of light soil is in pasture and grazed rather than cropped (self-replacing merino ewes at 2.5 ewes/ha).

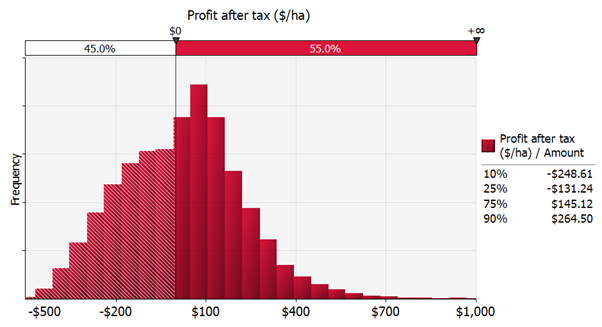

Distributions around yields, process and costs are created and substituted for average values. This enables a range of values to be generated, based on the frequency distributions of each risky input. So rather than just calculating a single profit (after tax) value, based on averages, a range of profit values are determined and represented based on the frequency in which they occur (figure 2).

Figure 2. Profit after tax for a 1500 ha west cropping Wimmera farm

Figure 2 shows the chances of not making a profit are 45.0% (the average profit is $33.10/ha).

While every farm is different some generalisations on the risk of different enterprise mixes can be made (based on analysis of approximately 40 mixed farms across Southern Australia).

Cropping is usually more risky than livestock

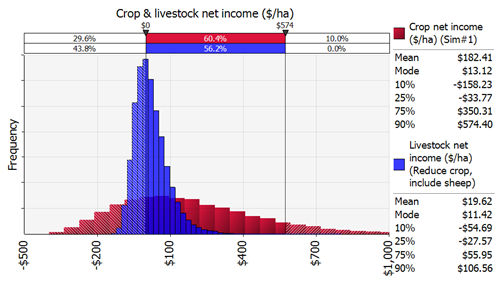

This is usually true, however risk also includes upside as well as downside risk. If the 500 ha of light soil was taken out of cropping and livestock run on this area instead, then the risk profiles of the two enterprises can be compared (figure 3).

Figure 3. Net farm income from cropping the heavy soil (red distribution) and livestock on the light soil (blue distribution).

This example clearly illustrates the contrasting net income distributions for the cropping enterprise compared to livestock. The cropping enterprise is flatter and wider compared with the sheep enterprise, indicating greater volatility in possible profits with the cropping enterprise.

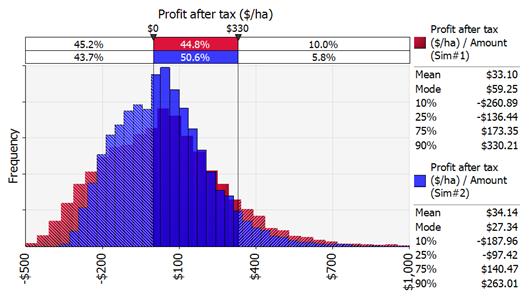

When the two are combined the addition of livestock reduce the volatility in farm profits, although the average income stays roughly the same (figure 4).

Figure 4. Profit after tax for all cropping (red distribution) compared to 1000 ha of cropping and 500 ha of sheep (blue distribution).

Other conclusions from the enterprise mix include:

- Intensification (say increasing stocking rate) generally increases risk

- Enterprise diversity usually decreases risk

- Sheep are usually more risky than cattle.

Conclusion

There is no single way to manage production risk. Many ‘levers’ influence the ultimate risk profile of a business and it is up to the individuals in that business to determine and feel comfortable with a level of risk that matches the rewards they seek.

Having said this, managing risk requires making decisions. The type of analysis used in Grain and Graze provides a very useful platform to inform discussion and decisions around risk.

References

Keogh M 2013, 'Global and commercial realities facing Australian grain growers' in robust cropping systems - the next step. GRDC Grains Research Update for Advisers 2013. ORM Communications, Bendigo, Vic. pp 13-30.

Nicholson C 2013, 'Analysing and discussing risk in farming businesses’. Extension Farming Systems Journal. Vol. 9 (1) Australasia Pacific Extension Network. pp 178-182.

Useful resources

Acknowledgements

The GRDC for funding the Grain and Graze program.

Contact details

Cam Nicholson

Nicon Rural Services

Grain and Graze

Email: cam@niconrural.com.au

GRDC Project Code: SFS00028,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK