Pulsating pulses — expanding pulse crops

Author: Storey (Marketing Services & Chairman, Pulse Australia) | Date: 13 Feb 2018

Take home messages

- Record Australian production and exports of lentil and chick pea in 2016 and 2017 — is it sustainable?

- Global demand and dietary shift towards better nutrition and sustainability is undeniable, but the commercial journey is not without bumps in the road — it requires patience.

- Underlying fundamentals for pulse products are very positive however this needs to be tempered by the short-term volatility in markets arising from significant government intervention, at times, to meet domestic political realities in the major pulse markets of the Indian sub-continent.

NOTE: At the time of preparing this update paper (early January 2018), there was significant market uncertainty due to recent announcements of import tariffs on pulses by the Indian Government. As a result the key messages will not change however some data in this paper may differ slightly from the updated information presented during February 2018.

Background

There has been a consistent theme over the past decade around rising populations, declining arable land and safe water, and the challenge to produce sufficient food. In grain markets, this has shown its face in rapidly rising demand for feed grains and protein meals to meet animal protein demand (poultry, pork, beef, dairy, etc.). Does this mean Australian grain growers can just hitch a ride on this ‘gravy train’? After all, with lentil and chick pea prices at A$700+ over the 2016/2017 seasons, it looked pretty straightforward! But by early 2018, we are back to $400 lentil prices — if there is a buyer! The answer is far more complex, and this applies especially to pulses. The future is bright but will require patience, and like anything that is worthwhile, it will require us to be the best in the business.

The emerging story — from protein, to health, to pulses

The ‘protein story’ is now quite well-worn. Rising populations and rising incomes drive demand for a shift to animal proteins (poultry, pork, dairy, beef, seafood, etc.), away from rice and noodles as staples. While this western diet trend is touted as ‘better’, it is also evident that the diseases of the West (diabetes, obesity, cancers, heart disease, etc.) are coming under increasing scrutiny as the link between diet and disease becomes better understood. So the ‘health and nutrition story’ is gaining prominence over the protein story in terms of food demand. Developing countries are not content to just see a McDonalds or KFC outlet as evidence of their rising incomes and prosperity; they are very concerned about food safety and provenance and the longer term impacts on health budgets as their populations grow older. It is in this context that pulses have an exciting future role to play in satisfying global food demand, not so much in a quantity sense, but more-so in the quality and nutrition of future foods. Quite apart from the growth in raw commodity pulses for the pulse market engine room of the Indian sub-continent (primarily India, Pakistan and Bangladesh), global food companies are starting to introduce pulses as ingredients into mainstream products and beverages. Will the ‘pulse story’ have a happy ending?

Reconciling the bright outlook with current market realities?

How does the positive future indicated by the above fundamentals line up with current market trends?

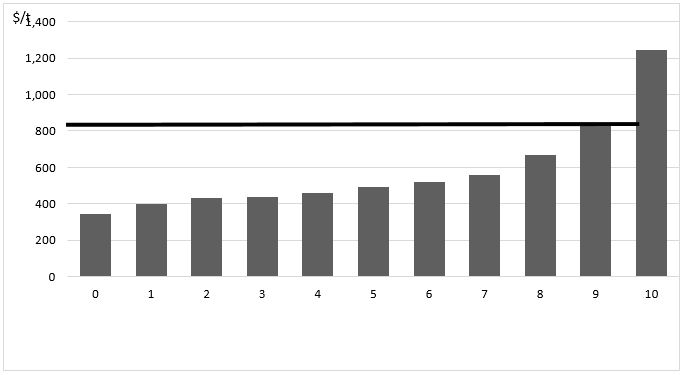

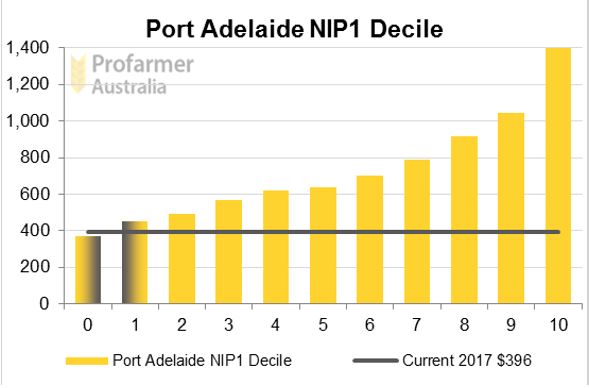

As one example, how do we go from $800/t (decile 9) lentil price in 2016/17, as per Figure 2.

Figure 1. Port Adelaide NIP1 lentil decile, January 2017 (Source: Profarmer Australia).

Figure 2. Port Adelaide NIP1 lentil decile 1, January 2018 (Source: Profarmer Australia).

The answer is a combination of seasons (failed 2015 and 2016 monsoons in India, coupled with an all-time record 2016 yields and production in Australia), followed by large Indian Government tariff duties to protect their local growers in late 2017. This level of price volatility helps no-one and we have to look past these short term spikes (both up and down), and ask whether there is a more sustainable, more certain future to justify the investments in varieties, standards and supply chains to sustain both reliable producers and importers?

We also need to appreciate the current market structures, where Australia may have a significant export position, but this can be more than overshadowed by the dependence on a single market.

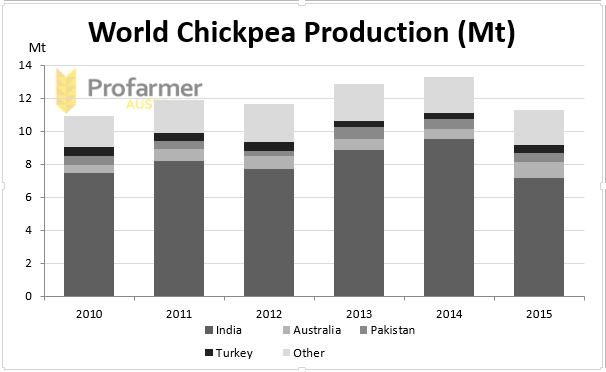

For example, in chick pea, Australia is the world’s largest exporter, but the overall chick pea market is dominated by India which produces about ten times Australia’s average production (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Chickpea – Australia (second bar from bottom of the column) is the largest exporter but India (first bar from bottom of the column) dominates production (Source: Profarmer Australia).

So, where to from here? — it’s a long term game

In the face of these current market realities (aka, typical commodity boom/bust scenarios) what are the prospects of sustainable, high value pulse crop options for Australian growers and exporters? If we were to be reliant on the general commodity cycle, then life will continue to be a challenge in terms of retaining pulses as a regular profitable option in the farming system. BUT, the reasons to be confident are compelling because the diet shift is not just a hope; it is consumer driven and the trend is under way. That is…

- What we eat matters; the demand for food origin and content will only increase.

- Millennials (18-35 year olds) are driving the change.

- Consumption of ‘better For you’ foods is outstripping traditional foods.

- Pulses are a stellar converter of water to protein — sustainability.

Additionally, the diet shift (gradual) is being played out in the food sector with traditional uses making way for novel and functional innovations (Table 1).

Table 1. The diet shift

From Traditional | To Novel |

|---|---|

Whole pulses | Flours, fractions |

Soups, sauces | Batters, breading, bakery |

Dips, spreads | Beverages |

Cook at home | Snacks, salads — ready to eat |

These trends in the food industry will require pulse supply chains which are targeted and sophisticated, capable of meeting demands of food processors for functionality, traceability and sustainability — not your typical commodity supply chain where lowest price wins. For Australia, this is good news as we are better suited to position ourselves for the ‘deli market’, not the ‘hypermarket’. But it does require time and patience to stay the course.

Conclusion

The 20+ year journey to introduce and successfully grow pulses by Australian growers, supported by Pulse Australia (with GRDC investment), seems to be well embedded and accepted as a good and sustainable practice from a farming systems point of view. Growers have the confidence to grow them. The marketplace for pulses however, continues to throw up the volatility challenge, with highly profitable prices at times and unprofitable prices at other times. The opportunity however, based on some pretty striking global fundamentals on what and how the next generations want to consume food looks particularly positive. Family farming, being a multi-generational pursuit, is well suited to keeping its finger on the pulse.

References

Data drawn from ABS, Profarmer Australia, Australian Crop Forecasters, Pulse Australia

Acknowledgements:

Ron Storey acknowledges the support of GRDC and its panel networks in requesting this input to the GRDC 2018 Grains Research Updates.

Contact details

Ron Storey

Storey Marketing Services

0418 332431

ron@storeymarketing.com.au

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK