Tactical sorghum agronomy for the central west NSW and key decision points affecting success

Author: Loretta Serafin, Mark Hellyer, Andrew Bishop and Annie Warren (NSW Department of Primary Industries, Tamworth) | Date: 23 Jul 2018

Take home messages

- Set a target yield based on soil moisture availability, seasonal outlook for rain and local yield expectations.

- Sorghum has a wide sowing window in most areas. Avoid sowing too early (cold) or too late (ergot and frost). Monitor rising soil temperatures to target the optimum time to sow. Aim to avoid flowering during the extreme heat of late December to early January.

- Match the plant population and row spacing to the target yield. Plant uniformity is important so where possible sow using a precision planter.

- Select at least 2 high yielding hybrids that have the desired characteristics (e.g. maturity, standability) for your growing conditions to spread production risk.

- Use registered knockdown herbicides to desiccate crops when they reach physiological maturity to hasten crop dry down, improve harvesting and commence the refilling of the soil moisture profile in dryland crops.

Introduction

Grain sorghum production in central west NSW is not a new phenomenon. In fact, 20 years ago it was recorded in the 2000-2001 ABS Statistics that 60 growers were growing close to 8,000 hectares of grain sorghum with an average yield of 2.6 t/ha.

The success of growing sorghum is largely founded on principles similar to other broad acre crops; the better your management practices, paddock preparation and in-crop rainfall are the higher the chance of economic yields and the lower the risk of poor crop performance or even failure.

Grain sorghum is a deep rooted perennial crop which is the backbone of many northern crop rotations and for good reasons. It is drought tolerant (to a point!), generally reliable, easy to manage and has several markets as grain marketing options. Sorghum is also a useful tool to vary herbicide groups to manage weeds, utilise variable summer rainfall and split labour, cash flow and peak logistical requirements in farm operations.

Starting soil water

Starting soil water is important to most crops, but the level of starting soil water available to sorghum is a strong indicator of likely crop yields especially without much in-crop rain. It has long been recommended to only sow sorghum when 100 cm of wet soil was available to plant into. This recommendation is based on minimising the risk of crop failure, as sorghum is subjected to high temperatures, high evaporation rates and more variable rainfall events during its growth cycle than winter crops.

Choosing to sow sorghum on a soil profile which is less than full, indicates two things; i) willingness to accept a higher risk of crop failure or poor yields (e.g. <2.0t/ha) OR ii) high expectations of above average in-crop rainfall.

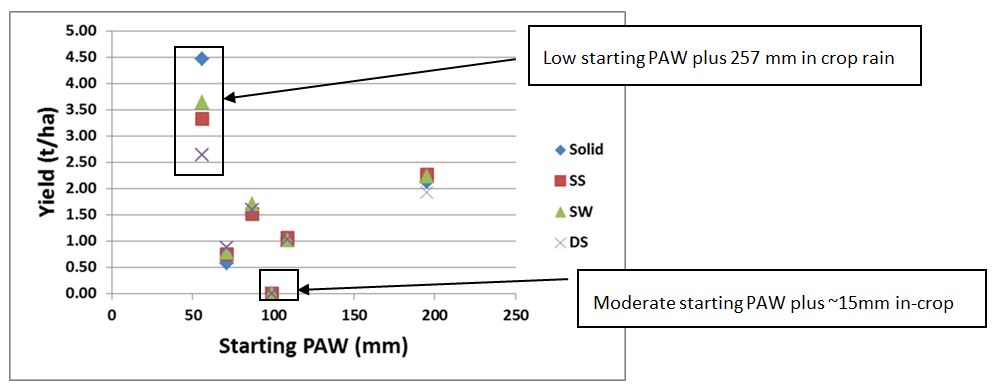

The interaction between starting soil water, in-crop rainfall and resulting grain yield was compared at a range of trial sites in north west NSW (Figure 1). At two of the sites, highlighted in figure 1; when starting plant available water (PAW) was low (<50 mm) but substantial well timed in-crop rain occurred, high yields resulted. In contrast, when starting plant available water was at a moderate level of ~100 mm and very little in-crop rainfall was received a crop failure resulted. This demonstrates that high starting soil water levels can reduce the risk of crop failure but not totally eliminate it.

Figure 1. Starting soil water and resulting grain yield from a selection of sites in northwest NSW

When is the best time to sow?

Traditionally, it has been said that sorghum should be planted when the soil temperature at 8 am AESDT at the intended seed depth (about 3–5 cm) is at least 16°C (preferably 18°C) for three to four consecutive days and the risk of frosts has passed. This is a very reliable method which should continue to be followed.

Recently in a GRDC and NSW DPI project there has been research experimenting with moving the sowing window forward by planting into cooler soils. While this practice could significantly widen the sowing window, it is also still currently a high risk option until further evaluation of a range of hybrids and environments is completed. The aim of this work is to be able to move the flowering and grain fill window away from the peak heat conditions in December and January.

In 2017-18 sowing at temperatures below 12°C halved the established plant populations when compared to sowing at the recommended soil temperatures of 16-18°C (Table 1). In addition the time taken to reach full emergence was up to 6 weeks following the sowing date. This exposes the seedlings to a higher risk of disease and insect attack but also did not always move the flowering window earlier in order to avoid heat stress at flowering and grain fill.

Table 1. Actual plant establishment at three sites in northern NSW under varying times of sowing

Site/ Sowing time | Super early | Early | Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

Target: 50,000 plants/ha | Plants/ha | ||

Gurley, east of Moree | 16,000 | 28,000 | 44,000 |

Mallawa, west of Moree | 19,000 | 25,000 | 41,000 |

Breeza, Liverpool Plains | 32,000 | 33,000 | 50,000 |

In contrast sowing late i.e. into January exposes the seeds to very high soil temperatures but milder grain filling conditions. It is a balance though to sow crops early enough to ensure flowering and seed filling occur prior to the onset of frosts. There is also a higher risk of ergot and slow grain dry down potentially requiring additional grain drying costs when sowing late.

Selecting a row spacing/ configuration and a plant population

Sorghum can be successfully sown on row spacing’s as close as 25 cm or as wide as a double skip on 100 cm configurations depending on the environment, starting water and likelihood of in-crop rain. However, the most common row spacing with yield expectations > 4 t/ha is 75 cm using a precision planter. Due to the tillering ability of sorghum, it will respond to neighbouring competition and environmental conditions to produce more or less tillers.

It is recommended to match your row spacing to your expected yield and your likely availability of soil water. As a rule of thumb, > 4t/ha use row spacing of less than or equal to 75 cm, for yields between 3-4 t/ha use 100 cm row spacing’s and for < 3t/ha using 100 cm or skip/wide row configurations. The advantage of wide or skip row spacing is the ability to conserve water in skip areas for flowering and grain fill as the plant roots don’t generally explore this area fully before flowering.

As a guide, aim to establish 50,000 plants/ha which still provides plenty of top end yield potential with most hybrids, (exceptionally low tillering hybrids might require higher populations) with potential for yields greater than 10 t/ha.

The use of precision planters enables less seed to be used, more uniform seed spacing to be achieved and as a result more even crop maturity and reduced seed costs.

Hybrid selection

There are a range of sorghum hybrids available on the market from seven different breeding companies. It is recommended to select at least 2 hybrids which have slightly different maturities to ensure flowering times are staged over a couple of weeks to reduce the risk of heat impacting on pollen viability and seed set. Ensuring the crop is not under undue moisture stress during the flowering and grain fill periods will also help to offset the impacts of excessive heat.

Desiccation

Sorghum will be “killed” by frosts at the end of the growing season if left late enough, however, it will re-grow the following spring if not desiccated. Desiccation is an invaluable tool for speeding up crop dry down and evenness of grain moisture, starting the fallow weed control process and stopping the use of soil water which could be preserved for the following crop.

Identification of the correct time to desiccate is crucial to ensuring maximum yield is achieved and additional water use is minimised. Check the lowest grains on the heads for the presence of a “black layer” which indicates the crop is at physiological maturity i.e. has stopped filling grain and is simply drying down and so a chemical desiccant can be applied.

The alternative to desiccation is to leave the crop to naturally dry down and then harvest once the grain moisture content is below 13.5%. This option is typically taken by growers with livestock who would like to utilise the remaining green feed but will mean the crop is standing in the paddock for longer.

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of NSW Department of Primary Industries and the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support.

Contact details

Loretta Serafin

NSW Department of Primary Industries

4 Marsden Park Road, Calala

Ph: 0427 311 819

Email: Loretta.serafin@dpi.nsw.gov.au

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK