Economic role of export hay within farming systems

Author: Mike Krause (P2PAgri P/L) | Date: 17 Aug 2018

Take home message

- The whole farm modelling with the inclusion of the export hay enterprise in the mid-north region of South Australia (SA) shows that export hay provides both improved profits and better climate risk management for the farming system.

- However, while the export hay enterprise can deliver both financial and agronomic benefits, it is not an enterprise that farmers can choose to go in and out of between seasons.

- Export hay production is an enterprise that requires high levels of management skill and dedication, as the rewards will only be available to those growers who implement a ‘continual management improvement’ approach to their business.

Background

The export hay industry has been an evolving industry in Australia and is becoming a significant part of the farming system within many medium to high rainfall areas. It can improve farm business risk management and control weed resistant issues in the farming system. The challenge for the export hay industry and the Australian Exporters Company (AEXCO) is to continue to expand production to ensure a significant and constant supply can be made available to valuable export hay markets.

This economic study of the role of export hay in selected farming systems in SA and Western Australia (WA) was funded by AEXCO. The study covers both the profits provided by the export hay enterprise and the effect on business risk. As this paper is being presented in Adelaide, it focuses on the SA component of this study. To download the full report, go to the AEXCO website.

This study was undertaken during February and March 2018, with significant grower and adviser input to validate the results and provide important farm business management information to support the expansion of the industry. The assumptions used in both the WA and the SA case studies are considered conservative by the respective farmers and advisers.

While this report outlines the key results from this study, the methodology and approach used in this study is robust enough to provide insight into any farm business management question when viewed from a farm’s business perspective.

Key question for research

The key question for research was to determine what business benefits are being provided to the growers who have an export hay enterprise in their farming system?

Method

A ‘Grower Case Study’ methodology was used where a farm was financially modelled to compare the ‘With’ export hay against the ‘Without’ export hay scenarios. Whole farm financial modelling helped clarify the important efficiency and risk management differences between the two scenarios.

The ‘Grower Case Study’ methodology included:

- Farm case study for SA: The SA ‘Grower Case Study’ has been modelled based on input from selected growers and an adviser. This was to avoid any issue with confidentiality in using a real farm and to be more representative of the industry. The adviser used to guide the development of the modelled assumptions was Mick Faulkner of Agrilink.

- Validation of data: A small group of growers and the adviser met in a half-day workshop environment to agree on the ‘Grower Case Study’ farm data, and to outline both the benefits and costs of having an export hay enterprise in the farming business.

- Data collection process: One grower was initially interviewed, and the base financial and physical data required for the respective ‘Grower Case Study’ was collected. This data was then used by the respective farmer/adviser group to develop the final ‘Grower Case Study’.

- Reporting parameters: Whole farm business measures and the scenario analysis approach outlined in the farm business management manual, ‘Farming the Business’, were used. This book was developed by Mike Krause and published by the GRDC (www.grdc.com.au/FarmingTheBusiness). Results of gross margin analysis, whole farm profitability and return on management capital were all used to report results.

- Risk profiles used: A range of seasons (Deciles 3, 5 & 7) were modelled to indicate the risk profile of each ‘Grower Case Study’ and the risk impact that the export hay enterprise had on the financial results of the business.

- Software used: A commercially available whole farm financial modelling software platform called P2PAgri was used to model the financial impact of the export hay enterprise on the respective ‘Grower Case Studies’.

The SA ‘Grower Case Study’

Export hay is grown in various regions in SA including the Mid-North, Upper South East and Upper Eyre Peninsula. Each area has different rainfall zones resulting in different farming systems. As this project only had resources to undertake this methodology in one region, it was decided to focus on the Mid-North region, particularly the Watervale area. This is because this region has the most experience with export hay production compared with the other SA regions.

Features of the ‘Grower Case Study’ area and farm enterprises are shown in Table 1

Table 1. SA ‘Grower Case Study’ area and enterprise selection.

Average rainfall: 620mm | ||

|---|---|---|

Enterprise | With export hay (ha) | With-out export hay (ha) |

Faba bean | 420 | 460 |

Barley | 175 | 200 |

Wheat | 525 | 600 |

Canola | 280 | 280 |

Export hay | 300 | - |

Pasture/self-replacing Merino | 300 (non-arable) | 400 (includes 300 ha non-arable) |

Total | 2,000 | 2,000 |

The major assumptions used in modelling the SA ‘Grower Case Study’ are:

- The mixture of hay, cereal grain, oilseed (canola) and grain legumes were seen to be typical of this area. It was felt that if export hay was removed from this farming system, pasture, oilseed and grain legumes would take up most of the difference as growers needed break-crops to maintain cereal production.

- The yield expectations for the SA ‘Grower Case Study’ ‘With’ export hay are shown in Table 2 and ‘Without’ export hay in Table 3.

Table 2. Yield expectations for the SA ‘Grower Case Study’ ‘With’ export hay.

Enterprise | Decile 3 (t/ha) | Decile 5 (t/ha) | Decile 7 (t/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

Faba Beans | 1.5 | 3.0 | 4.0 |

Barley | 3.5 | 5.0 | 6.0 |

Wheat | 3.3 | 4.8 | 5.8 |

Canola | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.2 |

Export Hay | 5.0 | 7.0 | 10.0 |

Table 3. Yield expectations for the SA ‘Grower Case Study’ ‘Without’ export hay.

Enterprise | Decile 3 (t/ha) | Decile 5 (t/ha) | Decile 7 (t/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

Faba Beans | 1.5 | 3.0 | 4.0 |

Barley | 3.5 | 5.0 | 6.0 |

Wheat | 3.3 | 4.8 | 5.8 |

Canola | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.2 |

There were no expected grain crop yield differences between the ‘With’ hay versus ‘Without’ hay scenarios. However, to compensate for some of the weed control benefits that the hay enterprise provides, variable costs for the ‘Without’ hay option are higher. These are shown in Table 4 and Table 5.

The advisory group felt that if the export hay enterprise was removed from the farming system, additional fertiliser and chemical would be needed for the barley and wheat enterprises to maintain grain production. This is to compensate for the weed control, improved fertility and root disease control which hay provides.

Table 4. Cropping variable costs for the ‘With’ export hay option.

Variable cost | Faba beans | Barley | Wheat | Canola | Cereal hay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Chemical | 150 | 150 | 160 | 150 | 50 |

Crop Insurance | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

Fertiliser | 50 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 100 |

Fuel | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 60 |

Repairs and maintenance | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 50 |

Seed | 40 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 30 |

Sundry | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

Total | 359 | 454 | 464 | 454 | 324 |

Table 5. Cropping variable costs for the ‘Without’ export hay option.

Variable cost | Faba beans | Barley | Wheat | Canola |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Chemical | 150 | 150 | 160 | 150 |

Crop Insurance | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

Fertiliser | 50 | 160 | 160 | 160 |

Fuel | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

Repairs and maintenance | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

Seed | 40 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

Sundry | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

Added fertiliser | - | 10 | 10 | - |

Added chemicals | - | 20 | 20 | - |

Total | 359 | 484 | 494 | 454 |

The grower and adviser group provided their expectations on prices given the various seasons modelled. It was felt that faba bean and canola prices were not correlated to local seasonal outcomes, as they were very dependent on export market conditions (i.e. local production levels do not influence price).

In contrast, barley and export hay prices were seen to be affected by local production levels. While malt barley production is preferred, feed barley was more likely to be produced, as grain quality was very seasonally dependent. The feed barley market was significantly dependent on local stock feed demand - the higher production levels typical of a Decile 7 season generally lead to lower prices.

Similarly, growers would prefer to sell all their hay to the higher priced export market. However, the reality is that quality of hay could not always be maintained due to seasonal vagaries and so a significant amount of hay is sold for stock feed. Like feed barley, the higher the local production of hay, the lower the hay prices.

Table 6 and Table 7 indicate the farm gate prices of the various grains and hay grown by the ‘Grower Case Study’.

Table 6. Price expectations for the farm ‘With’ export hay.

Enterprise | Decile 3 | Decile 5 | Decile 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

Faba Beans | $320 | $320 | $320 |

Barley | $215 | $200 | $170 |

Wheat | $255 | $240 | $210 |

Canola | $450 | $450 | $450 |

Export Hay | $210 | $180 | $140 |

Table 7. Price expectations for the farm ‘Without’ export hay.

Enterprise | Decile 3 | Decile 5 | Decile 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

Faba Beans | $320 | $320 | $320 |

Barley | $215 | $200 | $170 |

Wheat | $255 | $240 | $210 |

Canola | $450 | $450 | $450 |

Livestock

As the SA ‘Grower Case Study’ had 300ha of non-arable land, a self-replacing merino enterprise was run. Details of this enterprise are shown in Table 8. The advisory group said that livestock goes well with a hay production enterprise as it enhances the flexibility to manage seasonal variations. When export hay was removed from the farming system, 100ha of arable land became available for improved pasture, which has a significant carrying capacity of 20 dry sheep equivalent (dse)/ha.

Sheep were shorn twice each year to assist with sheep husbandry and increased wool production.

In the Decile 3 season, 12.5t of barley and 12.5t of hay were added as supplementary feed for the sheep enterprise in the ‘With’ export hay scenario. However, an added 20t of barley and 20t of hay were used as feed in the same season for the ‘Without’ export hay scenario, as more sheep are being carried.

The asset value of the ‘Without’ export hay scenario is higher because more ewe breeders are carried. The grower advisory group said that ‘the added capital needed for this livestock enterprise would come from the sale of surplus hay equipment’.

Table 8. Self-replacing ewe enterprise.

‘With’ export hay enterprise | ‘Without’ export hay enterprise | |

|---|---|---|

Grazing area | - | - |

Non-arable (ha) | 300 | 300 |

Arable (ha) | - | 100 |

DSE carrying capacity | - | - |

Non-arable (DSE/ha) | 11 | 11 |

Arable (DSE/ha) | - | 20 |

Breeding Ewes | 1,003 | 1,680 |

Flock DSE | 3,213 | 5,252 |

Livestock Asset Value | $311,310 | $510,730 |

Asset values and equity

Table 9 shows the asset base of the SA ‘Grower Case Study’. This uses the size of the property with recent market values for the land, machinery and livestock. The advisory group felt that about 20% of the total machinery value represented the value of the hay making machinery. In the ‘Without’ Export Hay enterprise, the hay making machinery would not be needed, but the group felt that the header would need to be upgraded as more grain would be harvested.

Table 9 provides a comparison of the ‘Grower Case Study’s assets in the ‘With’ and ‘Without’ export hay scenarios. The total assets do not change greatly between the two scenarios as money saved by not having hay making machinery approximately matches up with the increased assets needed for livestock purchases.

Table 9. Asset values of SA ‘Grower Case Study’.

Asset Items | ‘With’ export hay | ‘Without’ export hay |

|---|---|---|

Land | $20,237,000 | $20,237,000 |

Land related | $1,465,000 | $1,465,000 |

General machinery | $1,202,400 | $1,352,700 |

Hay making machinery | $300,600 | - |

Livestock | $311,310 | $510,730 |

Grain and hay on hand | $125,000 | $125,000 |

Total assets | $23,641,310 | $23,789,730 |

Liabilities

ABARES reports that Australian farm business equity is around 85%. The liability for the ‘Grower Case Study’ is $3,546,200, which is 15% of the total assets. This was modelled as an interest only loan with a 5.5% interest rate and was seen by the group as being a typical lending facility and interest rate.

Results

The farming system modelling results

This modelling has resulted in measuring the whole farm benefit to a farming system that has export hay as a part of the enterprise mix. This result is shown across a range of seasons and indicates how export hay assists with managing seasonal risk.

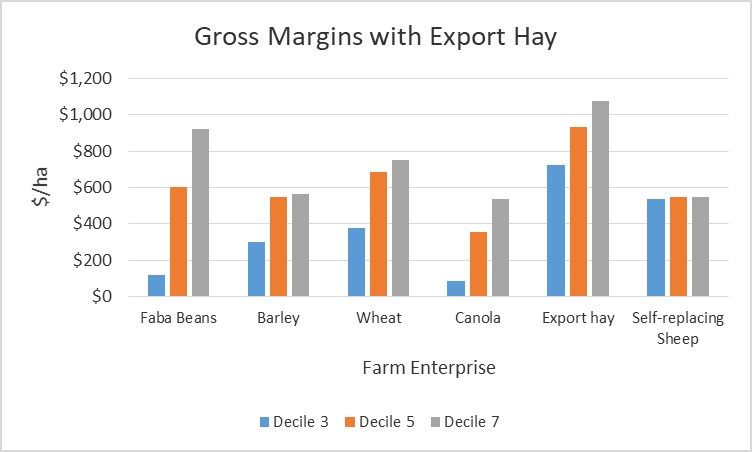

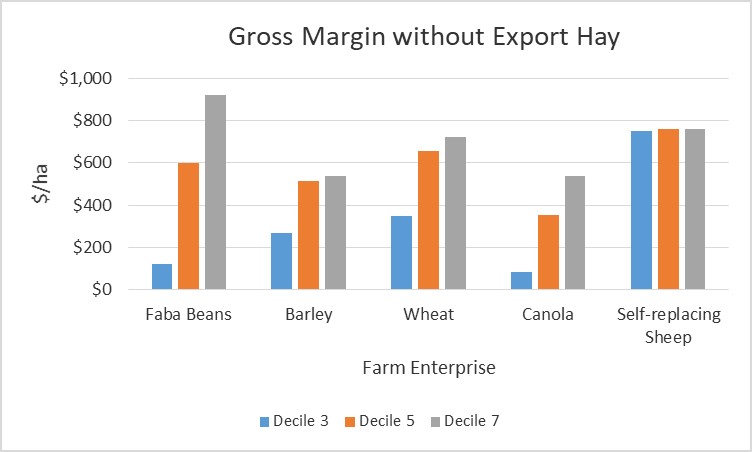

The enterprise gross margins form the ‘engine’ to create whole farm net profits. Table 10 and Figures 1 and 2 show the modelled enterprise gross margins for each enterprise for both the ‘With’ and ‘Without’ export hay enterprises.

Table 10. Expected gross margins for each of the enterprises given the different seasons modelled.

Season type | Decile 3 | Decile 5 | Decile 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

Faba Beans | $121 | $601 | $921 |

Barley | $299 | $546 | $566 |

Wheat | $378 | $688 | $754 |

Canola | $86 | $356 | $536 |

Export Hay | $726 | $936 | $1,076 |

Self-Replacing Merino | $550 | $550 | $550 |

‘without’ export hay | |||

Faba Beans | $121 | $601 | $921 |

Barley | $269 | $516 | $536 |

Wheat | $348 | $658 | $724 |

Canola | $86 | $356 | $536 |

Self-replacing merino | $763 | $763 | $763 |

These gross margins highlight:

- The export hay enterprise provided the highest gross margin in each season type in the ‘With’ export hay scenario. This indicates both its profitability and ability to assist with the risks associated with seasonal variation.

- The cereal grain gross margins are poorer without the export hay because variable costs are higher with added chemicals needed for more weed control and added fertiliser required to deliver the same yield expectations.

- The self-replacing merino gross margin, while not providing the highest gross margin, was least affected by the seasonal variations. Also, with the current good wool and livestock prices, this enterprise provided the third highest gross margin of all the enterprises studied.

- The self-replacing merino enterprise provided higher gross margins per hectare in the ‘Without’ Export Hay scenario as 100ha of arable land was used for improved pasture, which provided a significant increase in livestock production.

Figure 1. Enterprise gross margins for the ‘With’ export hay scenario.

Figure 2. Enterprise gross margins for the ‘Without’ export hay scenario.

Whole farm profitability

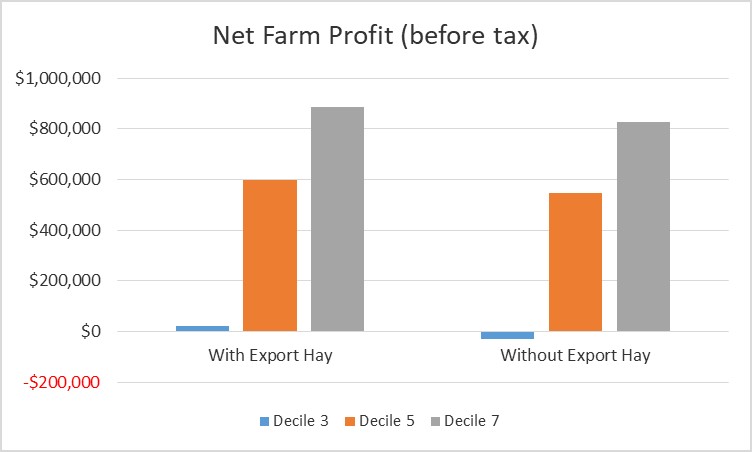

A primary aim of business is to generate profits. One of the tests when assessing the effect of any change on the business is to measure the effect on profits from that change. Table 11 and Figure 3 show the modelled results of the financial effect of export hay on the ‘Grower Case Study’ in the three season types.

Table 11. Net farm profit before Tax comparing the ‘With’ and ‘Without’ export hay in the ‘Grower Case Study’.

Season Type | Decile 3 | Decile 5 | Decile 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

‘With’ Export Hay | $21,567 | $596,687 | $1,058,770 |

‘Without’ Export Hay | -$31,200 | $546,900 | $828,189 |

These results indicate that the inclusion of export hay in this ‘Grower Case Study’ provided added net farm profit across the three season types modelled. The main observations:

- The 9.1% increase in net farm profit in an average season (Decile 5) is substantial.

- The inclusion of export hay meant that profits were improved in all seasons assessed. There are measurable benefits from export hay when it comes to managing seasonal risks.

- In the scenario of ‘Without’ export hay, the ‘Grower Case Study’ made losses in the Decile 3 season, while in the same season, the ‘With’ export hay provided a small net farm profit.

Figure 3. The net farm profit results for both the ‘With’ and ‘Without’ export hay scenarios in three season types (Decile 3, 5 & 7).

Whole farm efficiency

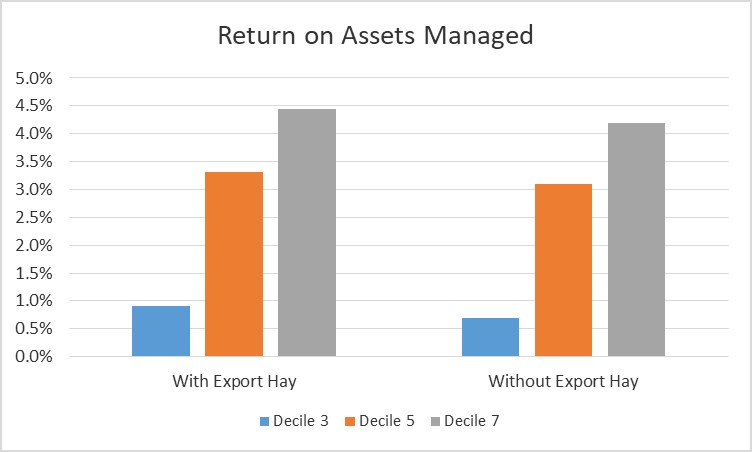

While comparing the two scenarios, it is also important to assess the business efficiency improvement that export hay provides the ‘Grower Case Study’. Business efficiency is measured by return on assets managed (ROAM), with the highest value indicating the best result. Table 12 and Figure 4 indicate the efficiency result of this modelling:

- The efficiency results of both the ‘With’ and ‘Without’ export hay indicate relatively low returns for the industry. These results are reflective of the high land values of the SA ‘Grower Case Study’ of $4,500/ac for the arable area. Industry would say a 6% ROAM would be more desirable.

- Efficiency is improved by the inclusion of export hay in all season types studied.

- The ‘With’ export hay ROAM of 3.3%, represents a 7.4% improvement in efficiency compared to the ‘Without’ export hay scenario.

Table 12. Return on Assets Managed comparing the ‘With’ and ‘Without’ export hay in the SA ‘Grower Case Study’.

Season Type | Decile 3 | Decile 5 | Decile 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

‘With’ Export Hay | 0.9% | 3.3% | 4.4% |

‘Without’ Export Hay | 0.7% | 3.1% | 4.2% |

Figure 4. The business efficiency results for both the ‘With’ and ‘Without’ export hay scenarios.

Further observations from the SA grower and adviser workshop

The adviser and growers who participated in the half-day workshop that was conducted as part of this project provided a list of both the advantages and challenges of an export hay enterprise:

Advantages provided by the export hay enterprise

In the discussion with the growers and adviser, the following advantages were identified from having export hay in a farming business within this area in SA:

Improved profitability

- There is a good balance of risk and financial reward. There are instances when strong profits can occur and other times when significant losses occur. It was generally agreed that the higher risks were matched with the higher rewards.

Improved risk management

- The advisory group felt that the export hay enterprise offered greater risk management of dry finishes and frost. This gave the business balance; when a season was good for grain production the farm profits came from this, and when the season was not favourable for grain production the farm profits came from hay.

Agronomic advantages

- Improved management of resistant ryegrass in the farming system.

- Improved ability to conserve moisture for the following year.

Response to climate variability

- The hay enterprise tended to do better in a dryer finish.

- The effect of frost is minimised as frost does not tend to affect hay yields and quality.

- The hay enterprise gives flexibility in managing climate variation. Hay can be cut in a season that finishes early, or the crop could be left to grain production in a good season. Note, this tended to be a comment regarding hay production and not specifically export hay, as export hay was seen as a speciality enterprise that cannot be managed opportunistically.

Labour utilisation

- The month leading up to grain harvest can be quiet on a farm, so hay-making provides permanent staff with significant work in this period of the year.

- Hay making, while a hectic period, helps to spread the work load more evenly throughout the year.

- As hay making requires less spraying, this reduced pressure on the farm’s workforce.

Grazing capability

- Hay making paddocks can be grazed early in the season before the paddock is shut up and grown out for hay harvest. This allows more grazing to be available at a time when there may be a lean pasture supply.

Improved pest control

- It has been reported that a hay enterprise encourages less slugs in the farming system.

- Less mice have also been reported as hay means less grain is spilled at harvest, leaving less food available for mice after harvest.

Technology improvements

- Improvement in technology has significantly helped with hay making to produce better bales. This has improved freight handling and lowered freight costs.

- There are now improved weather warnings which greatly help with the hay making process.

- In-field weather stations now measure weather more accurately, which means the art of hay making can be further improved.

- The technology of mower conditioners has greatly improved; leading to better quality control.

- The technology of balers has also improved; leading to improved labour efficiencies.

Challenges provided by the export hay enterprise

Agronomic challenges

- The hay enterprise creates poor management of the following weeds: barley grass, resistant wild oats and brome grass.

- Hay-making and carting machinery can be heavy. In moist soil conditions at hay making, there may be significant compaction issues.

- The process of hay making means within paddock operations do not maintain ‘control traffic’ paths.

The cash flow challenge

- Hay enterprises create a monthly income to the business which was seen as useful. However, it was mentioned that grain payment for cash flow was better as money comes in within two months of harvest, whereas hay payments may take up to ten months after harvest.

Management issues

The management issues of the export hay enterprise were listed as critical, as management needs to be fully committed in order to achieve the quality needed for export hay. This enterprise will not be profitable if it is not managed to a high standard.

- Growers who do not manage stress well may find operating a hay making operation very difficult. This is due to the affect weather has on both production and the quality of hay. Weather events throughout the hay-making period can occur quickly and require quick decision-making and follow-through of those decisions.

- If farm management does not handle stress well, then hay-making can add to increased personal risk.

- The intensive work-load that is required to make high quality export hay can have a significant impact on sleep patterns due to stress.

- There are difficulties managing a worker’s eight-hour day because baling can occur anytime in a 24-hour period. This can lead to OH&S issues of fatigue management.

- Due to the ’24-hour hay-making cycle’, a grower’s/worker’s lifestyle is challenged for the four weeks of hay making. This can be a strain on family relationships.

Production issues

- The levels of both quality and production are greatly affected by weather events through spring. For example, a rain at the wrong time can spoil hay in the processing period. If drying conditions do not occur after these rain events, then the value of this hay will be adversely affected.

- Hay is a bulky product, so growers need expensive equipment to transport and handle the hay, otherwise there will be OH&S issues.

- As the hay making process is very time sensitive, the reliability of machinery is very important.

- Hay making starts earlier in the season, which means the overall harvest period, including grain, is quite an extended period. Sound fatigue management is needed.

- Poor management during the hay making period can cause hay stacks to spontaneously combust, resulting in a significant financial loss.

- Contamination of hay with unwanted weeds, vermin and snakes can reduce quality, which may lead to export hay rejection issues and OH&S issues.

- The stacking of bales can be challenging and lead to OH&S issues.

Disease

- Different diseases can be introduced to the farming system, including stem nematode and bacterial blight.

Marketing issues

- Growers have experienced payment issues in the past from some hay processors. This risk seems to have decreased as the industry has matured but can still be an issue.

- Growers need to develop rapport with the hay processors and need to manage this relationship. If growers do not wish to manage this marketing relationship, then selling hay can become more difficult, resulting in poorer prices or produce not being accepted.

- The commitment to export hay is needed over many seasons to both master the quality requirements of export hay and demonstrate to the hay processors that hay will be supplied through both good and poorer times.

- The export hay market does not reward those growers who speculatively produce.

Conclusion

This study has provided a comprehensive analysis of the economic role that an export hay enterprise provides to farming systems in two regions, Narrogin, WA and Watervale SA, both of which are considered as medium to high rainfall zones. Only the SA results are discussed in this paper. While these economic results are specific to the regions selected for this study, elements of the discussions can be used as general observations for other hay-making regions of Australia. While these results are relevant for 2018, the range of seasons modelled make these results applicable to a wide range of seasons. It can be concluded that export hay provides both improved financial performance and a significant strategy to manage business and agronomic risks.

Useful resources

The full report of this study titled ‘Evaluating the Economics of Export Hay in Selected Farming Systems’ can be downloaded from the AEXCO website.

The farm business methodology can be further researched in ‘Farming the Business’ by Mike Krause, a manual in farm business management funded by GRDC.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge The Australian Exporters Company (AEXCO) for funding this project into understanding the economic role the export hay enterprise has in selected farming systems in SA and WA. To follow is a statement on the activities of AEXCO:

The Australian Exporters Company (AEXCO) shareholders are the major export oaten hay processors of Australia. AEXCO was selected by the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI) as the successful company to commercialise new hay varieties beginning in 2001. Since 2001 AEXCO has launched seven oat hay varieties, Kangaroo, Wintaroo, Brusher, Mulgara, Tungoo, Tammar and Forester onto the market. The AEXCO shareholders (the major Export Hay processors) believe research and development of oaten hay varieties is a critical component in growing Australia’s export oaten hay industry. AEXCO’s primary purpose is to support the National Oat Breeding Program (NOBP) research and development activities for all oat hay industry participants.

I also would like to thank Mick Faulkner of Agrilink who provided significant guidance into the assumptions used in this modelling. He, along with four SA export hay growers, guided the development of the assumptions used in the modelling.

Contact details

Mike Krause

Plan2Profit Agri P/L, Adelaide

08 8396 7122, 0408 967 122

Mike@P2PAgric.com.au

www.P2PAgric.com.au

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK