Building a resilient business

Author: Chris Minehan (Rural Management Strategies Pty Ltd) | Date: 25 Jun 2019

Take home messages

- Essential components of a resilient production system include soil fertility, soil moisture when it’s needed, low weed and disease burden, and diversity.

- Resilient farm businesses have an ability to ride out periods of poor production and bounce back when conditions improve

- For a family farming business to be resilient, all members must have a clear understanding of the goals and direction of the business

Characteristics of resilient farm businesses

A resilient farm business is built upon a strong, resilient and sustainable production system, though this alone does not guarantee success. The days of focusing on maximising yields and letting the dollars look after themselves are long gone.

This paper explores resilience in three ways:

- Resilience of the farming system,

- Resilience of the business, and

- Resilience of individuals and the family.

Resilience of the farming system

A resilient farming system deals with the challenges of climate, biotic and abiotic factors and the vagaries of commodity markets by:

- Producing income in the face of adverse climatic conditions.

- Avoiding, or physically recovering from impacts of drought/frost/heat.

- Capturing favourable conditions without extra spending.

Essential components of a resilient production system include:

- Soil fertility.

- Soil moisture when it’s needed.

- Low weed and disease burden.

- Diversity.

All of these are achieved through a sound and stable paddock rotation plan.

Soil fertility

Soil fertility is measured in terms of organic carbon (OC), nutrient cycling and nitrogen (N) mineralisation.

- Even the best cropping practices reduce OC%.

- Fertility can be built up with perennial pastures.

- Fertility can be maintained with manure crops / cover crops.

Continuous cropping without a pulse crop leads to a decline in soil fertility, meaning more urea is required for the same grain yield.

Fertile soils provide extra N in good years, automatically, where spring rain leads to extra mineralisation. Higher yields and grain quality with no extra spending!

A dense, productive legume pasture grown for four years provides enough N for three to four crops that follow the pasture in the rotation. Urea should only be required for crops in the later stages of the crop rotation. (This does not mean paddocks of barley grass, silver grass and capeweed.) Mixed farms that have paddocks in crop or pasture for too long are missing the key benefits of this system. Instead, during the cropping phase spending on weed control and N will increase, while pastures become sparse and weedy.

Good whole-farm planning, at least three years into the future, is required to achieve the key benefits and minimise the extra spend.

Soil moisture when it’s needed

Fundamentals for capture and storage of plant available water (PAW):

- Summer fallow weed control.

- Maintaining groundcover in fallows and pastures. Once pasture growth is low enough to require supplementary feeding, stock should be put into drought lots, so pasture productivity is not permanently damaged.

Identify crops with the most critical need for water. In most operations this is canola at establishment. Ensure canola goes into a situation where PAW at sowing is maximised. Many pulse crops leave residual PAW and organic N for canola. Brown manured legumes such as vetch or field peas leave even more PAW and N. Long fallows can also be utilised to ensure there is PAW when it is needed most.

Subsoil constraints such as sodicity, acidity and physical compaction/high bulk density need to be understood and managed. These constraints may stop crops accessing moisture down the soil profile. Some paddocks still have moisture at depth from 2016, crops haven’t been able to reach this moisture due to subsoil constraints. Dig a soil pit and engage experts to assess the limitations.

If you can’t manage the constraint, manage your expectations and don’t spend money on unrealistic targets.

Weeds and disease

Resilient production systems have low levels of weeds or disease, managed through crop rotation and planning, not extra spending. Too many cereal crops in succession leads to a build up of root diseases such as crown rot and common root rot, which limit yield even when symptoms are not apparent. These paddocks also require more spending on grass weed control and urea to maintain yields.

Paddocks in a poor rotation, no matter how much money is thrown at them, are not able to capture higher yields in the good years due to weed and disease constraints, plus low fertility. Continually expecting canola to control three to four years of ryegrass seed-set in cereals is leading to herbicide resistance development, most worryingly to clethodim. Where canola is only mopping up low numbers of grass weeds (e.g. ryegrass), it remains very effective.

The cheapest and most effective time to manage grass weeds is when paddock is sown to broadleaf crops or pastures. Two consecutive years of complete control is required to effectively manage ryegrass. A double break of pulse followed by canola is very effective for managing ryegrass and cereal diseases. Brown manure pulse followed by canola is even better.

Diversity

In nature, the most resilient systems have a high degree of diversity. Resilience declines with diversity loss.

Farming systems with diversity of enterprises, diversity of crop and pasture type and diversity of income streams are inherently more resilient. These businesses are also more complex, due to the extra planning and management that is required. You don’t get anything for nothing.

If, for many good reasons, diversity is foregone in pursuit of simplicity, scale and focus on a single enterprise, other measures must be taken to ensure resilience is not lost. Having all crops flowering in the same frost window is a current limitation of many cropping enterprises, especially as into the future, the frost window is expected to become wider and more intense. Development of new, high-value safflower varieties may provide an alternative break crop that does not flower in the same frost window as all other crops.

Brown Manure Crops

- Primarily pulse crops such as vetch or field peas, though starting to incorporate a range of species for plant and microbial diversity.

- Sown early to maximise biomass, N fixation and competition with weeds.

- Sprayed out in September, before weeds set seed.

- Provide excellent groundcover through summer, large amounts of organic N and PAW for the next crop.

- Follow with canola to achieve double break on weeds and root diseases.

Incorporating brown manure crops into rotations increases the yields of subsequent crops for two to three years. More importantly, cropping costs are dramatically reduced, which increases profitability, reduces risk and improves resilience. The reduced cropping area is offset by higher yields and lower costs.

A single year gross margin analysis of brown manure crops never finds them to be as profitable as continuous cropping, as this type of analysis usually compares results to farm average yield or yield target and underestimates costs while overestimating yield potential of foregone crops.

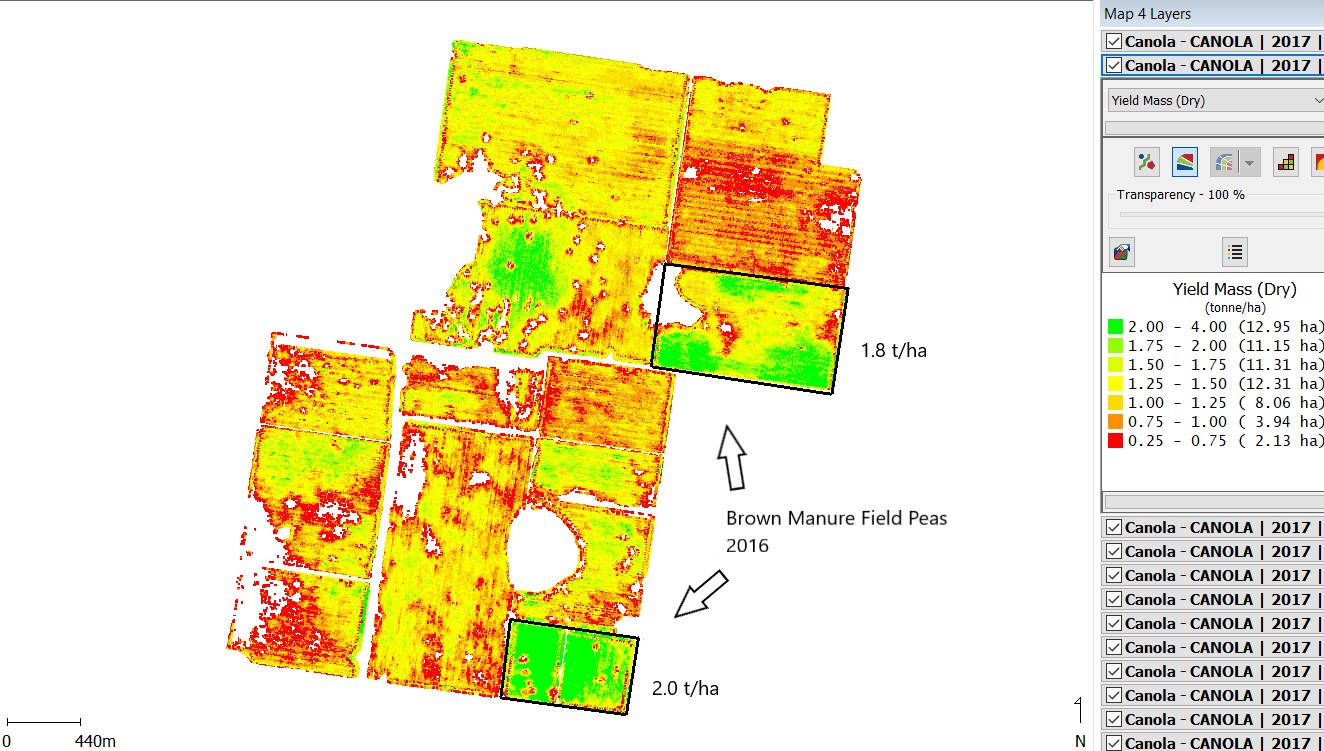

In reality, the worst performing paddock on a farm often has a negative gross margin, so these paddocks should be targeted first. A double break using a brown manured pulse crop can turn the worst paddock on a farm into one of the best, as shown in the example to follow.

Example

- All barley 2016, except the two least productive paddocks (mainly due to grass weeds).

- These two paddocks were brown manured field peas ($100/ha cost).

- Barley 2016

3.0 t/ha @ $170/tonne average Income $510/ha

Waterlogging, grass weeds and disease

Boxer Gold® + Axial® in-crop, urea spread by plane Variable costs $280/ha

. Gross Margin $230/ha

- All canola 2017

Canola paddocks that followed barley 2016 crop averaged 0.8 t/ha.

Canola paddocks that followed the brown manured field pea 2016 crop averaged 1.9 t/ha (Figure 1), which is 60% higher yield.

Figure 1. Yield map of 2017 canola crop.

Figure 1. Yield map of 2017 canola crop.

- Extra canola yield 2017 1.1 t/ha @ $550 /tonne $605/ha

No Sakura® on brown manured paddocks 2018 $40/ha

Less the cost of growing peas - $100/ha

. $545/ha

Net benefit of brown manured field peas (so far) $315/ha

Vetch is increasingly favoured in the brown manure role as it offers additional opportunities for cashflow in the ‘year out’:

- Livestock trading or adjistment if infrastructure allows,

- hay, and/or

- grain.

Newer vetch varieties such as Timok have very low levels of hard seed, so are more suited to cropping enterprises.

Farm business resilience

Resilient farm businesses have an ability to ride out periods of poor production and bounce back when conditions improve. The following characteristics are common to farm businesses that demonstrate resilience:

- Sound production systems which generate good revenue, at relatively low cost. Able to stop spending in dry times, without sacrificing yield potential.

- Marketing strategy that provides cashflow and profitability.

- Appropriate finance structures:

- An appropriate finance structure needs to ensure that the business has access to capital throughout the production cycle. Profitable decisions should not be put off due to a lack of cash.

- Businesses need to understand what is working capital which is to be repaid each year and what is core debt as a result of expansion and investment which is to be paid down periodically in good times and drawn on during tight periods. Crop only businesses require different finance structures to mixed farm businesses, which have money coming in more regularly.

- Equipment finance should be utilised for machinery purchases, so that capital can be retained for purchasing land and other appreciating assets. Loan repayments should be structured to match real depreciation. There is no point to having large amounts of equity in depreciating assets, when all you need is the access to that machine.

- Likewise, infrastructure upgrades should be funded through schemes such as the Rural Assistance Authority (RAA) Farm Innovation Fund, rather than tying up bank finance on these long-term investments.

- Cost structure: resilient businesses have a relatively low-cost structure for their productive capacity. These businesses retain more of their income as profit. This can be achieved by increasing income, reducing costs, or preferably both. This seems obvious, however businesses that do not adequately plan get trapped into high-cost production models, spending money to fix issues that could be addressed at a much lower cost, if not for free. Grains industry pressure to maximise yields often at low margin, rather than achieving good yields at high profit also contributes to this problem. Many unrequired inputs are justified on the basis of being ‘just a few dollars per hectare’ however these all add up and contribute to low margins overall.

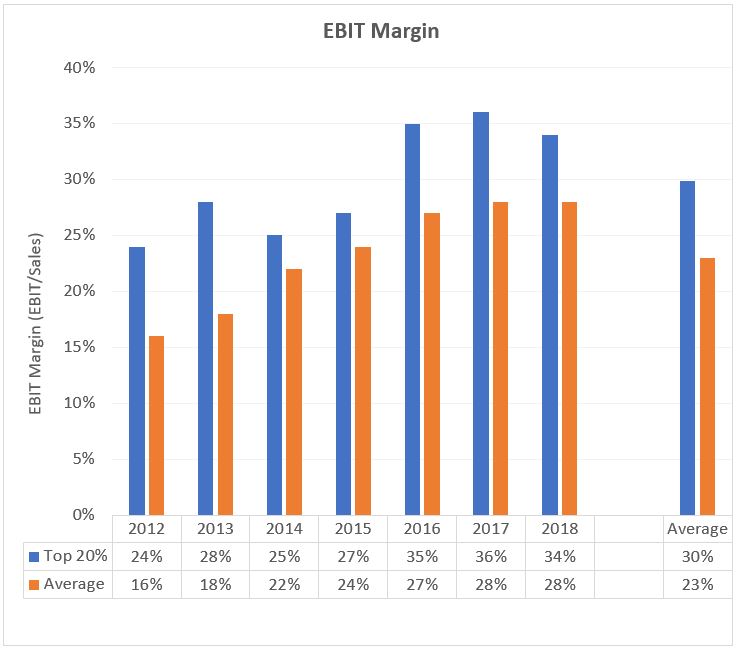

Cost structure can be measured through Cost of Production (CoP) and Earning Before Interests and Taxes (EBIT) Margin.

CoP for a commodity can be determined by summing the variable costs, allocating a portion of fixed costs and dividing that by the total amount of commodity produced. CoP is generally calculated before interest and tax. Adding a portion of the total interest expense allows a Break-Even Price (BEP) to be determined, which is useful for a grain marketing strategy. For grain sales, a profit margin of 30% above the BEP is a good target. The process is similar for livestock, determined on a basis of $/head for lambs and $/kg for wool.

EBIT Margin refers to the margin between income and expenses, before interest and tax. A business with an EBIT margin of 30% spends $70 for every $100 of sales. A business with an EBIT margin of 20% spends $80 for every $100 of sales. The business with the lower EBIT margin is a higher risk business, as it has more money on the table when things go wrong. Figure 2 shows the EBIT Margin for average and top 20% of Rural Management Strategy clients since 2012. Assuming $1,000,000 of income, the 7% difference between the groups across the period would equate to an extra $70,000 per year in EBIT.

Figure 2. EBIT Margin for average and top 20% clients since 2012 (Source: Rural Management Strategies).

- Appropriate business structure: the most appropriate business structure for a farm business depends on a range of factors including the number of family members involved, both on- and off-farm, the age of key people, the assets managed by the business and many other factors.

The structure of the business is very important for:

- Business operations,

- asset protection,

- taxation, and

- business transition / succession to the next generation.

If you’re not sure whether your business has the right structure, talk to a farm business adviser.

- Resources matched to the requirements of the business: businesses that are over-capitalised with machinery and labour for the productive area are less resilient when poor seasons occur. Aim for fixed costs to make up less than 40% of total costs before interest. Table 1 provides some targets for key business performance indicators.

Smaller farms should consider syndicating large machinery items such as headers, to reduce the cost and risk of owning these items.

Table 1. Business Key Performance Indicators.

KPI | TARGET | |

|---|---|---|

EBIT Margin | 25-30% | A measure of how much gross profit (Earnings before Interest and Tax) is retained as a percentage of sales. An EBIT margin of 30% means $70 is spent for every $100 earnt. A higher EBIT margin means the business has a lower level of risk and is more profitable. |

Equity % | 75-80% | A measure of the amount the business owns compared to its debts. Businesses with good cash generation and high EBIT margin can operate at lower equity levels but are exposed to poor seasons. Businesses with higher equity have a greater buffer for adverse conditions. |

Interest Cover | > 2 | The number of times that EBIT covers the interest obligations of the business, including bank loans and machinery finance. An interest cover of <1 means the business is not generating enough gross profit to cover interest. |

Fixed/Variable cost ratio | 40/60 | Fixed costs must be met whether the business plants crop that year or not. Lower fixed costs per hectare makes a business more stable and resilient to poor growing seasons. Increasing scale through purchase or leasing dilutes fixed costs across a greater area. |

Return on Assets | 3-5% | A measure of business performance used across many industries, allowing business owners to compare returns generated by money spent within the business against alternative investments off-farm. |

Personal and family resilience

For a family farming business to be resilient, all members must have a clear understanding of the goals and direction of the business, so everyone is pushing in the same direction. This makes a huge difference when times get tough.

- Confidence comes from knowing where you’re heading.

- Farming families need a vision of where they want to be in 5, 10 and 20-years’ time both as a business and as individuals.

- Most problems within farming families (probably families in general) stem from poor, or no communication. Parents want to know that they can provide opportunities for their children. The younger generation on the farm want a career path mapped out for them within the business, while those off-farm want to feel they are valued and considered.

- A long-term vision for the business and family members allows short and medium-term goals to be set along the way so that the long-term vision is achieved. Short term decisions can be tested against the overall direction of the business.

Planning

Underneath short to medium term strategies, businesses require immediate plans for how the business operates. Such plans include:

- Production plans: cropping plan for this year (and next) and livestock and pasture plans.

- Marketing strategy.

- Financial plan and budgets.

- Capital investment and infrastructure plans.

Planning has to be done well in advance, not in the heat of the battle.

“The time to repair the roof is while the sun is shining”.

- John F. Kennedy

Making good decisions

The best plans in the world are useless without confident decision making. Managers need to be considered, but decisive. Trust your instincts, make the decision and move on. Learn from your mistakes, but don’t dwell on them.

Looking after yourself and your family

In order to make good decisions, managers need to be mentally and physically sharp. Give yourself permission to look after yourself, that means:

- Proper nutrition

- Regular exercise

- Adequate sleep, especially during busy times

- Holidays

Holidays are really important for farming families, especially in periods of hardship. It doesn’t need to be a ski trip to Aspen, but it needs to be away from the farm and for at least seven days. Everyone needs time to unwind, de-stress and regain perspective. Holidays need to be put into diaries and calendars otherwise they won’t happen. Don’t wait for all the jobs to be done or you will never leave. Plan and prioritise, the other jobs will still be there when you get back. If jobs can’t be left, such as feeding livestock, ask neighbours or others in the community to do yours, then cover them in return. People want to help each other, but often feel awkward about asking and offering. Turn off technology or go somewhere with no service.

Safety in numbers

Resilient and successful businesses utilise expert advice. This allows them to get on with executing the plan and doing the things that they are best at. Seek out professionals who are prepared to work as part of a management team and who are committed to the success of your farm business.

Regular meetings with trusted advisers, away from the daily activities of farming, allows for more strategic decisions to be made with clarity and confidence. Business meetings may only need to be twice annually during periods of business stability, but more regularly around major events like property purchasing or as the business transitions to the next generation.

Family and community

Resilience comes from a loving family and a sense of community

Planning ahead creates time for family and community by cutting through the decision paralysis that eats up time.

Conclusion

A resilient farm business not only has a strong, resilient and sustainable production system, it also focuses on developing farm business resilience and personal and family resilience. Achieving resilience in all three components allows the business to achieve its greatest success.

Contact details

Chris Minehan

chris@rmsag.com.au

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK