Feathertop Rhodes grass ecology and management. What strategies are working best?

Author: Richard Daniel (Northern Grower Alliance ), Hanwen Wu (NSW Department of Primary Industries) and Mark Congreve (Independent Consultants Australia Network) | Date: 12 Aug 2020

Take home message

- Feathertop Rhodes grass is well adapted to colonise bare ground (fallows, roadsides)

- Commitment to two summers of 100% control of feathertop Rhodes grass should deplete the seed bank in the soil

- Control strategies require an integrated approach that includes tillage, crop selection, maximising crop competition, residual herbicides and selective use of double knock applications in fallow.

Feathertop Rhodes grass (Chloris virgata) (FTR) continues to be a major problem weed in zero till farming systems in the northern grains region, with populations continuing to expand further south, particularly along road corridors.

Biological factors that influence control strategies

Feathertop Rhodes grass is a prolific seed producer which can produce up to 40 000 seeds per plant under optimal conditions. However, when plants are under moisture stress, they will quickly begin setting viable seed, even when the plant is small/young.

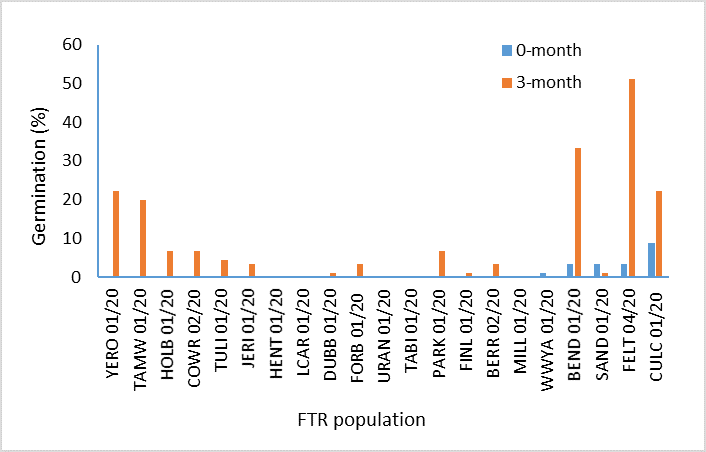

It appears to have a short dormancy period, with poor germination for the first few months after shedding.

Figure 1. Germination percentage of different FTR collections soon after shedding (Hanwen Wu. NSW DPI)

FTR is often the first weed to establish on bare ground following a rainfall event in spring/summer, although it can germinate at all times of the year (including winter).

Glasshouse studies by Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (Werth 2017) showed that FTR will emerge following as little as a 10 mm simulated rainfall event (Figure 2) however larger rainfall events resulted in increased emergence.

Awnless barnyard grass, common sowthistle and flaxleaf fleabane were also included in this study (data not shown). The rainfall requirement for emergence of FTR was less than for awnless barnyard grass, especially at the lower temperature tested, while rainfall >20mm was required to provide significant emergence of sowthistle and fleabane. This ability for FTR to establish on lower rainfall highlights one of the reasons that FTR is often the first weed to establish following spring rainfall.

Figure 2. Percentage FTR emergence with respect to temperature and rainfall

In a second trial in the same study, different amounts of rainfall were simulated over consecutive days (Figure 3). Keeping the soil surface moist for a longer period typically increased the percentage emergence compared to a single application of the same total amount of rainfall.

Figure 3. Percentage FTR emergence with multiple rainfall events

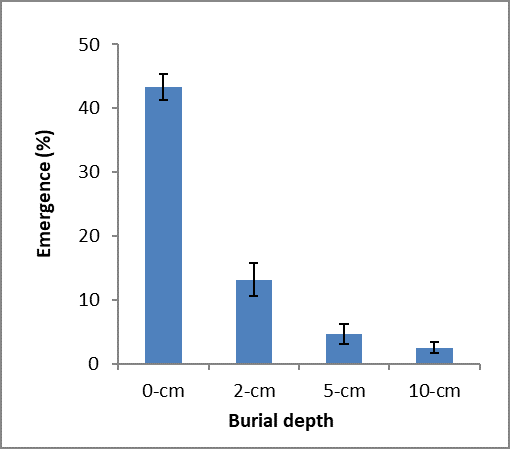

Feathertop Rhodes grass is predominantly a surface germinator, with minimal germination occurring from seed below the top 2 cm in the soil (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Effect on emergence of FTR seed burial (Hanwen Wu, NSW DPI)

Pot trial -duplex red Kandosol soil, pH 5.4 and organic carbon 0.6%.

The combination of surface germination and germinating on less rainfall than competitor weeds means that FTR is well adapted to zero till fallows and other bare areas (such as roadsides sprayed with glyphosate).

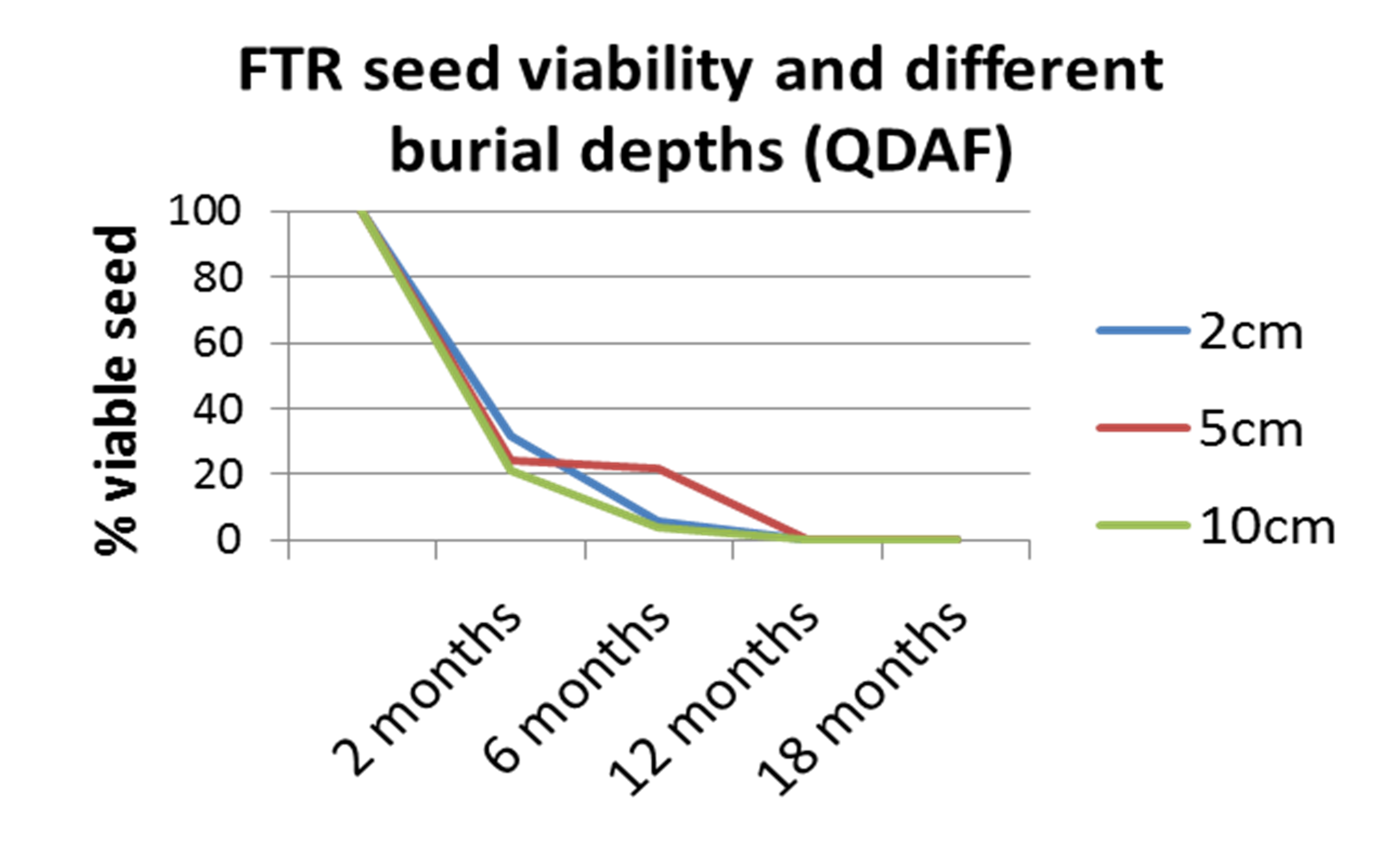

Seed persistence is short. Viability of seed declines rapidly and almost no seed remains viable 12-18 months after shedding (Figure 5). Unlike most other weeds, studies have shown that burying seed does not significantly increase persistence.

Figure 5. FTR persistence over time

Adapted from QDAF (2014) Integrated weed management of feathertop Rhodes Grass

This lack of seedbank persistence can be utilised as the proverbial boxer’s ‘glass jaw’ in management of FTR – a concerted effort over two consecutive summers to completely stop seed set and any further recruitment into the paddock can see paddocks rapidly go from infested to effectively clear of FTR in a couple of years.

Feathertop Rhodes grass does not compete well with existing crops or pasture. However, it often is the dominant species in any bare areas (eg. roads, fallow) right up against the edge of the crop or pasture paddocks.

These factors see FTR quickly dominate bare earth roadsides or zero till paddocks, especially following wet summers where control programs have not been able to stop seed set and recruitment into the seed bank.

Outside of the cropping paddock, residual control can be achieved by the use of imazapyr based herbicides (e.g. Arsenal®) in non-crop areas. The flumioxazin based herbicides Terrain® and Valor® have recently obtained registrations for residual control along fencelines and irrigation channels respectively.

The first punch – prevention is better than cure

Control of established populations of large FTR is difficult, extremely costly and most likely to be incompatible with zero till farming. Therefore, growers should aim to keep FTR out of farming paddocks wherever possible, and urgently seek to remove individual plants before they have a chance to set seed.

Where glyphosate has been used on roadways and fence lines and FTR has then become established, seed can be blown into adjacent paddocks. Alternatively, seeds may be deposited in the paddock via livestock and kangaroos; from machinery or in flood water.

Typically, a single plant in year 1 will result in a small clump covering maybe 2-3m2 in year two. Over coming years these patches will continue to expand, potentially seeing the whole paddock infested if nothing is done to stop seed set.

Growers should be continually on the lookout for individual plants and act quickly to manually remove or spot spray these before they are allowed to set seed. Small patches should be chipped, burnt or cultivated to prevent spread. Ideally these should be GPS mapped for future monitoring with a residual herbicide applied prior to the commencement of spring rainfall events.

The second punch – knockdown herbicides

Glyphosate alone is not registered for control of FTR and cannot be expected to achieve control (Widderick 2014, Douglas 2019). Even when using a double knock of glyphosate followed by paraquat under ideal conditions and targeting seedlings before they start tillering, control is variable and rarely provides a commercially acceptable result.

Targeting larger weeds that have commenced tillering, or are under any stress, will typically achieve less than 50% control as a double knock, and often not significantly better than using paraquat alone as a single application.

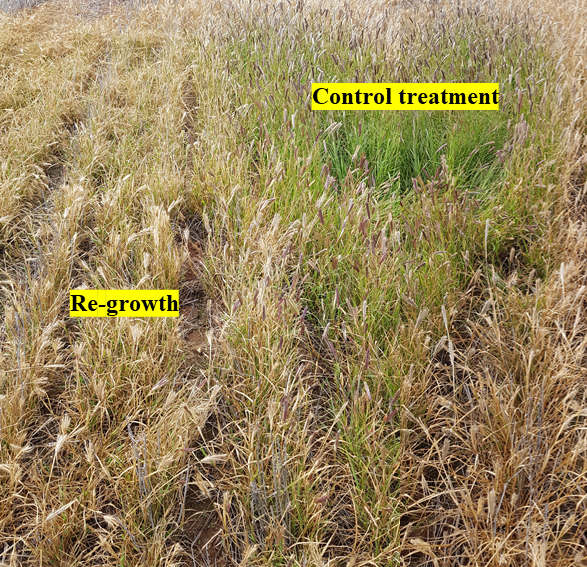

Figure 6. Re-growth (left) with single knock of glyphosate (540g ai/L) at 1.44L/ha

(not registered for FTR) (Photo: Hanwen Wu)

Research trials and commercial experience have shown that Group A herbicides can be effective in providing useful control.

Shogun® (propaquizafop) is registered for the control of feathertop Rhodes grass in fallow and in cotton, peanuts and sunflower. In fallow, Shogun must be applied to weeds at the 3-leaf to early tillering growth stage and followed with an application of paraquat within 7-14 days (double knock).

Firepower 900 (haloxyfop) has recently been registered for control of FTR in fallow. (Note: this is the only haloxyfop formulation approved for use on FTR in NSW). Weed size is restricted to 2 leaf to early tillering (Z12 to Z22) and for FTR, this should always be followed by a paraquat double knock.

The APVMA has also recently approved an emergency permit that supports the use of clethodim formulations for control of FTR in fallow (PER89322 – Expires 31 August 2021, for NSW and Queensland only). This must also be followed by a paraquat double knock application within 7-14 days. While there is no weed size recommended on the permit, it should be noted that trial work has consistently shown that clethodim is generally slightly less effective than ‘fops’ on FTR, so limiting application to seedlings or very early tillering is strongly advised.

The importance of weed growth stage is critical for the performance of Group A herbicides (Figure 7 & 8). As weed size increases, translocation of the herbicide reduces throughout the plant. Once plants move from vegetative production to reproductive growth, production of the enzyme targeted by the Group A herbicide reduces in the plant. Further information explaining this can be found in the GRDC Fact Sheet ‘Group A Herbicides in Fallow’.

Figure 7. Effect of weed size and timing of Shogun on FTR (Adama, unpublished)

Figure 8. Effect of weed size +/- double knock of haloxyfop on FTR

(Central Queensland Grower Solutions Project 2011-15)

When applying Group A herbicides, ensure the correct adjuvant is used and application set up is optimised for coverage. Typically, this will be a medium-coarse spray quality, with water rates of 80 to 100 L/ha.

Avoid tank-mixing other herbicides which may reduce the performance of Group A herbicides (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Haloxyfop tank mixes against FTR (NGA, Crooble 2014. RN1433)

Experience in other grass weed species has shown that Group A herbicides are one of the quickest modes of action to select for resistance as there is typically a high frequency of resistant individuals in the natural population.

For this reason, all Group A applications in fallow must be followed by a double knock; they should only be targeted at small weeds; and should not be used more than once per season.

It is essential that this mode of action is protected from resistance selection. Group A herbicides are the mainstay of post-emergent grass weed control in summer broadleaf crops.

The third punch – tactical cultivation

Where FTR has got out of hand and established plants are present, it is likely that tillage will be needed to remove existing weeds.

It is unlikely that any herbicide treatment will provide consistent cost-effective control of mature plants. Where old, established plants remain from last summer they can frequently shade herbicide application, thus leading to unsatisfactory results from subsequent knockdown or residual herbicide applications.

Removing mature plants via cultivation can be very effective. Burial of seed below 5cm can also reduce emergence and this seed will lose viability within about 12 months (providing it is not subsequently returned to the soil surface by further tillage).

While an effective cultivation may bury the vast majority of seed, there is always a small percent of seed remaining at the soil surface in the preferred germination zone. If something is not done to prevent these seeds from germinating and establishing, then the cycle recommences.

A plan should be in place to manage these subsequent germinations via either tillage, knockdown or residual herbicides.

The knockout blow – residual herbicides

The most successful strategies employed by growers for managing FTR have included the use of residual herbicides. Either directly targeted at known FTR problem paddocks, or more broadly, by keeping FTR at bay when targeting other grass weed problems on the farm. The viability of most other grass weed seeds in the soil is much longer than for FTR, so where growers are incorporating residual herbicides into their program to manage grass weeds such as awnless barnyard grass, FTR is often also controlled or suppressed.

Balance® can be a particularly effective option for fallow management. In addition to residual control of FTR, it will also control flaxleaf fleabane and common sowthistle with suppression of awnless barnyard grass, however significant plantback periods apply for many summer crop options.

Dual® Gold is registered for residual control of FTR prior to planting a wide range of summer crops and also in fallow situations, with minimal plantback constraints. A new use pattern also allows for a top-up application in sorghum after crop emergence.

Valor, applied at rates for residual control, is also an option prior to planting selected summer crops. Plantback periods apply for some summer crops when using Valor, so always check the label. In addition to control of FTR, Valor can also provide residual control of a range of difficult to control broadleaf weeds such as fleabane, sowthistle, red pigweed, caltrop, bladder ketmia and the Ipomea species such as bell vine and morning glory.

Most residual ‘grass’ herbicides are active on FTR however the length of residual control is a function of environment at the site; the soil type and stubble; and the individual properties of the herbicides. Chose the ‘grass’ residual herbicide that fits the farming system within that paddock.

Figure 10. Summary of 22 residual herbicide trials (2007-2016) (NGA, QDAF, GOA, NSW DPI)

Blue 14-48 DAA Orange 58-77 DAA Grey 81-147 DAA

*Not all treatments in all trials. Some trials had more than one rate. Some trials had two ratings within the same time grouping.

Screening of residual herbicides registered for use in winter cereal or pulses is showing a promising range of options that can suppress FTR emergence for periods of three to four months. These may be options to consider in areas where spring temperatures are warmer and FTR is establishing in-crop during spring.

Going the full ten rounds – pulling it all together

Where there has been a ‘blow out’ and a paddock has become infested with FTR, it is likely that a management strategy will look something like the following:

- Cultivation of established plants (before seed has been shed)

- Residual herbicide applied if there is still the possibility of further germination before winter

- Aggressive crop competition (and pre-emergent herbicides) in the winter crop

- Decide on your strategy for summer before the first spring rainfall event, and potential weed germination

- If fallowing over summer, apply a residual herbicide before spring rainfall. Monitor frequently for any escapes or breakdown of the residual herbicide. Access to an optical (camera) sprayer can be beneficial in cost effectively treating isolated escapes. Once the residual treatment has broken down, a double knock application will be required, with consideration given to including another residual application with the second knock

- Where soil moisture is adequate, consider a summer broadleaf crop (or cotton where suitable). Use a pre-emergent herbicide effective on grass weeds; keep row spacing narrow and plant population high to increase the benefit of crop competition; and utilise a selective Group A ‘fop‘ herbicide in-crop to control any escapes. Inter-row tillage is also a valid strategy in wide row summer crops.

- Do not plant sorghum or maize into paddocks with a high FTR seed bank population. Pre-emergent herbicide options such as Dual Gold are unlikely to provide full season residual control, even at the highest application rate – especially in wet seasons. Late season germinations can establish after the pre-emergent herbicide has broken down

- If FTR is not allowed to set seed, then seed bank viability should be low the following year. Continue vigilant management for another season to ensure depletion of the seed bank.

Unfortunately, the best management strategies for this difficult to manage weed place great reliance on herbicides; and therefore, selection of resistant individuals. Glyphosate is ineffective and Group A herbicides are known to be of significant risk of rapid selection for resistance. While there is currently negligible resistance in the northern grains region to many of the pre-emergent herbicides with efficacy on this weed, one thing we have learnt from history is that if we over-rely on a particular herbicide or herbicide group and don’t stop weed seed set of survivors, then we will break it.

References

Widderick, M., Cook, T., McLean, A., Churchett, J., Keenan, M., Miller, B., Davidson, B. (2014) Improved management of key northern region weeds: diverse problems, diverse solutions. Environmental Science.

Douglas, A. & Hashem, A. (2019) Feathertop Rhodes grass (Chloris virgata): Seed ecology and herbicide resistance status of a new weed threat to Western Australia. GRDC Updates

QDAF (2014) Integrated weed management of feathertop Rhodes Grass

Werth, J., Keenan, M., Thornby, D., Bell, K., Walker, S. (2017) Emergence of four weed species in response to rainfall and temperature. Weed Biology and Management. Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of these projects have been made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the authors would like to thank them for their continued support.

Contact details

Richard Daniel

NGA

PO Box 78, Harlaxton Qld 4350

Ph: 0428 657 782

Email: richard.daniel@nga.org.au

Hanwen Wu

Wagga Wagga Agricultural Institute

NSW Department of Primary Industries

Pine Gully Road, Wagga Wagga, NSW 2650

Ph: 02 6938 1602

Email: hanwen.wu@dpi.nsw.gov.au

Mark Congreve

ICAN

PO Box 718, Hornsby. NSW 1630

Ph: 0427 209 234

Email: mark@icanrural.com.au

® Registered trademark

GRDC Project Code: NGA00003, NGA00004, DAN1912-034RTX, ICN1912-002SAX, DPI1912-034RTX,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK