Managing annual ryegrass in the high rainfall zone

Author: Christopher Preston & Fleur Dolman (School of Agriculture, Food & Wine, The University of Adelaide) and James Manson (Southern Farming Systems) | Date: 24 Feb 2022

Take home messages

- Mixtures and sequences of pre-emergent herbicide are required for effective control of annual ryegrass in the HRZ.

- Harvest Weed Seed Control (HWSC) can be a valuable extra tool in the HRZ, despite more ryegrass seed shattering before harvest.

- Double breaks in rotations are the key to longer term management of annual ryegrass.

- Tactics need to be stacked each year for profitable annual ryegrass control.

Annual ryegrass is challenging to manage in the high rainfall zone

The long crop growing season of the high rainfall zone (HRZ) means that emergence of annual ryegrass is extended and late emerging annual ryegrass plants are still able to set a considerable amount of seed. In addition, there is widespread resistance to post-emergent herbicides in annual ryegrass. This means that annual ryegrass escaping pre-emergent herbicide control can easily repopulate the seed bank, maintaining high weed numbers.

Mixtures and sequences of pre-emergent herbicide are required for effective control of annual ryegrass in the HRZ

The high levels of resistance to post-emergence herbicides means that pre-emergent herbicides are the main means of annual ryegrass control in cereal crops. The extended emergence of annual ryegrass makes pre-emergence control difficult in the high rainfall zone. The use of pre-emergent herbicides as mixtures or as sequences with Boxer Gold® used early post-emergent can increase the amount of control achieved by having more persistence of the herbicides.

The introduction of new pre-emergent herbicides in recent years has offered new options for annual ryegrass control across all crops. However, the more mobile pre-emergent herbicides are more challenging to use in the HRZ. These herbicides can more easily be moved into the crop root zone resulting in crop damage, or leached out of the root zone of weeds, resulting in poor weed control. The registration of Mateno® Complete as an early post-emergent option in wheat has the potential to improve annual ryegrass control through its greater persistence in the soil compared with Boxer Gold.

Is harvest weed seed control viable in the HRZ

The long cropping seasons in the HRZ tend to result in annual ryegrass maturing and shedding substantial amounts of seed before the crop is ready for harvest. This means the efficacy of harvest weed seed control (HWSC) tactics is lower in the HRZ than in other regions (Table 1).

Table 1: Amount of annual ryegrass seed shed in HWSC trials in the HRZ prior to harvest.

Trial | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

Lake Bolac, Vic | 50% | 31% | 0% |

Yarrawonga, Vic | 57% | 65% | |

Conmurra, SA | 59% | 65% |

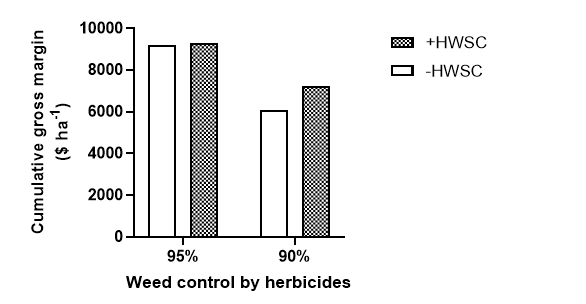

However, HWSC can still have value in the HRZ, as it helps reduce weed populations for future years. Modelling of the influence of HWSC on annual ryegrass populations and the effects of weed competition with crops suggests that 30% reduction in seed inputs will be beneficial, provided that the extra costs of HWSC are less than $34/ha. The benefits may be greater if herbicide control is compromised (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cumulative income after 12 years of a simulated wheat-barley-canola rotation, with or without a weed seed impact mill (HWSC) that removes 30% of weed seeds at harvest, and with effective herbicide control (95% of weeds killed) or less effective herbicide control (90% of weeds killed).

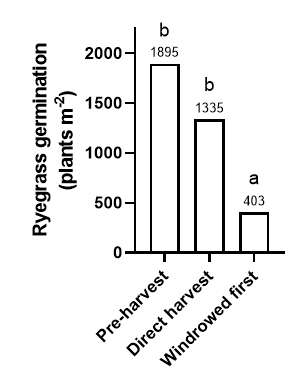

Windrowing crops can lead to less ryegrass shedding and more seeds are able to enter the front of the header. A paddock trial at Conmurra comparing direct harvest with an impact mill to windrowing and then harvest showed that windrowing first was able to greatly reduce the amount of annual ryegrass that germinated in the next year (Figure 2). The higher biomass of crops in the HRZ also means that costs of HWSC can be higher due to slower harvest. Some growers manage this by harvesting most of the crop at the normal height and dropping the header front low when they run into patches of annual ryegrass.

Figure 2. Annual ryegrass germination from plant and soil samples taken pre- and post-harvest at Conmurra, where direct harvest and windrowing strategies were used with an impact mill. Different letters indicate treatments that were significantly different.

Double breaks in rotations are the key to longer term management of annual ryegrass

As there are few effective controls for annual ryegrass in cereals in the HRZ, other than pre-emergent herbicides, break crops are an opportunity to greatly reduce annual ryegrass numbers. However, single break crops in rotations tend to just slow the rate of increase of annual ryegrass numbers. Break crops allow the use of clethodim and butroxydim as post-emergent herbicides, which still provide some level of control of annual ryegrass, and effective crop-topping. These tactics are not available in cereal crops. A double break, by reducing annual ryegrass seed set 2 years in a row has the potential to re-set annual ryegrass numbers.

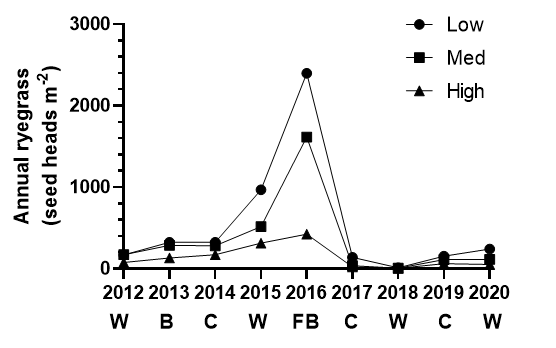

This was demonstrated in a long-term trial at Lake Bolac from 2012 to 2020. This trial compared three herbicide strategies, low, medium and high cost, for the control of annual ryegrass. From 2012 to 2016 annual ryegrass increased with all three strategies. The increase in annual ryegrass numbers (as measured by seed heads at harvest) was much lower in the high cost herbicide treatment, but herbicides on their own were not effective in reducing annual ryegrass numbers. A double break of faba beans followed by canola in 2016 and 2017, where both crops were crop-topped allowed a large reduction in annual ryegrass numbers in all three herbicide strategies. These low numbers were maintained in the medium and high cost herbicide strategies through 2020.

Figure 3. The mean effect of herbicide strategy on annual ryegrass seed heads/m in a nine-year trial at Lake Bolac. “W” is wheat, “B” is barley, “C” is canola, “FB” is faba beans. There are significant differences in all years except 2017.

Tactics need to be stacked each year for profitable annual ryegrass control

The Lake Bolac trial also demonstrated the value of stacking herbicide tactics. The high cost strategy was able to maintain annual ryegrass populations and, by reducing the impact on crop yield, provided a cumulative $1613/ha gross margin advantage over the low cost strategy over the 9 years of the trial.

A trial at Frances across 2019 and 2020 comparing increasing intensities of management also showed that increasing management intensity that reduces annual ryegrass numbers leads to improved profitability. In this trial, the most intensive management strategy (MS 4) provided a $300/ha cumulative gross margin advantage over the least intensive management strategy (MS 1).

Table 2: Yield for wheat in 2019 and faba beans in 2020 at Frances with four management strategies (MS1 to MS 4) and cumulative gross margins for the management strategies across the two years. Different letters after values in each column indicate significant differences.

Management strategy | Yield (t/ha) | Cumulative gross margin ($/ha) | |

|---|---|---|---|

2019 | 2020 | ||

MS 1 | 6.2 c | 3.8 ab | $3,772 |

MS 2 | 6.2 c | 3.5 b | $3,642 |

MS 3 | 6.7 b | 3.9 ab | $3,926 |

MS 4 | 7.1 a | 4.0 a | $4,072 |

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support.

Useful resources

Managing annual ryegrass in the High-Rainfall Zones of Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania

Contact details

Chris Preston

School of Agriculture, Food & Wine

University of Adelaide

0488 404 120

christopher.preston@adelaide.edu.au

GRDC Project Code: UA1803-008RTX, SFS1507-003RTX, SFS1904-003WCX,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK