Fungicide management and timing - keeping crops greener for longer in the high rainfall zone

Author: Nick Poole and Tracey Wylie | Date: 27 Aug 2014

Take home messages

The following paper contains extracts from the GRDC publication “Advancing the management of crop canopies – keeping crops greener for longer” - N. Poole and Dr J. Hunt published in January 2014.

Foliar fungal diseases and leaf area duration

In disease susceptible cereals, the benefit of a fungicide for disease control impacts most strongly on yield if it creates differences in green leaf duration after anthesis. However, for any given disease pressure, the principal driver of leaf area duration is soil water availability and temperature, not fungicide. Thus, the decision to apply a fungicide to prolong green leaf duration must be made in the knowledge that soil water and temperature have the overriding influence and that fungicide application is an insurance input.

Linking disease management with crop physiology - fungicides as canopy management tools

Fungicides do not create yield they only protect an inherent yield potential that the crop would have produced in the absence of disease. This is achieved by protecting the plants sources of carbohydrate production for grain fill; the leaves, leaf sheaths, stem and head. Although there are claims of yield enhancement in the absence of disease, under Australian conditions where grain fill is frequently curtailed by dry conditions it is better to centre fungicide strategies on disease management rather than crop greening alone.

In terms of disease management it is important to remember that the plant has two distinct sources of carbohydrate for grain fill; soluble stem carbohydrate reserves that are stored prior to peak flowering (GS65) and the carbohydrate produced by the leaves stem and head for direct grain filling after flowering has finished (GS71 – 89). Before flowering (GS60-69) the plant is using most of its resources to develop a bigger crop canopy. At head emergence (GS50-59) as the development of the canopy reaches final expansion, carbohydrates are increasingly diverted to storage in the stem (since there are no fertilised grain sites yet to fill). The relative importance of these two sources of carbohydrate changes as you move from low rainfall to higher rainfall regions. In the HRZ the period of carbohydrate production after anthesis increases in importance as these crops generally have higher soil water reserves and experience cooler temperatures during the grain fill period. Ideal grain fill conditions occurred in many parts of the Victorian HRZ last season with November temperatures notably below average, in some cases by as much as three degrees. Under these circumstances crops stay greener for longer provided that disease has been excluded from the crop.

How should fungicide strategies be adjusted when moving from lower rainfall regions to a high rainfall zone?

In regions of lower rainfall the leaf area duration (LAD) of the crop canopy is reduced post-anthesis, in effect the flag leaf and flag-1 do not stay as green for as long. Under these circumstances the post-anthesis contribution (in terms of photosynthesis) of the two top leaves to yield is reduced (although, pre-anthesis, these leaves may have contributed to the soluble stem carbohydrate reserves which are later mobilised to the grain). Under these circumstances the value of any fungicide application will be reduced, therefore strategies for fungicide application need to reflect this:

- In the lower rainfall zones where stressed grain-filling periods are more common, the target for a single fungicide can be earlier than flag leaf emergence (GS37-39), since the flag leaf is relatively less important to protect from disease and humidity and in the crop itself is generally less favourable for disease development. In these cases the emergence of the flag-2 and flag-1 leaves at second-third node GS32-33 becomes a more important target for a single spray application.

- In the high rainfall zone (HRZ) the top two leaves of the canopy are generally more productive after flowering and any fungicide strategy that omits to protect these leaves will not provide optimal returns. Therefore the optimum timing for a single spray tends to be later in the HRZ usually timed at flag leaf emergence (GS37-39). This does not mean that earlier sprays aren’t important, but rather that the timing of those earlier sprays should be calculated to ensure that there is no more than a 3- 4 week time interval between sprays. This usually results in the first fungicide being applied at first – second node (GS31-32). If disease pressure is maintained in the 3 – 4 weeks following the first application, the timing of the flag leaf spray becomes more crucial, since early sprays do not directly protect the two top leaves.

Protecting the crop with fungicide at early stem elongation and flag leaf will control developing disease in susceptible cultivars but have its greatest effect on the crop canopy during grain fill as LAD or green area duration (GAD) is extended.

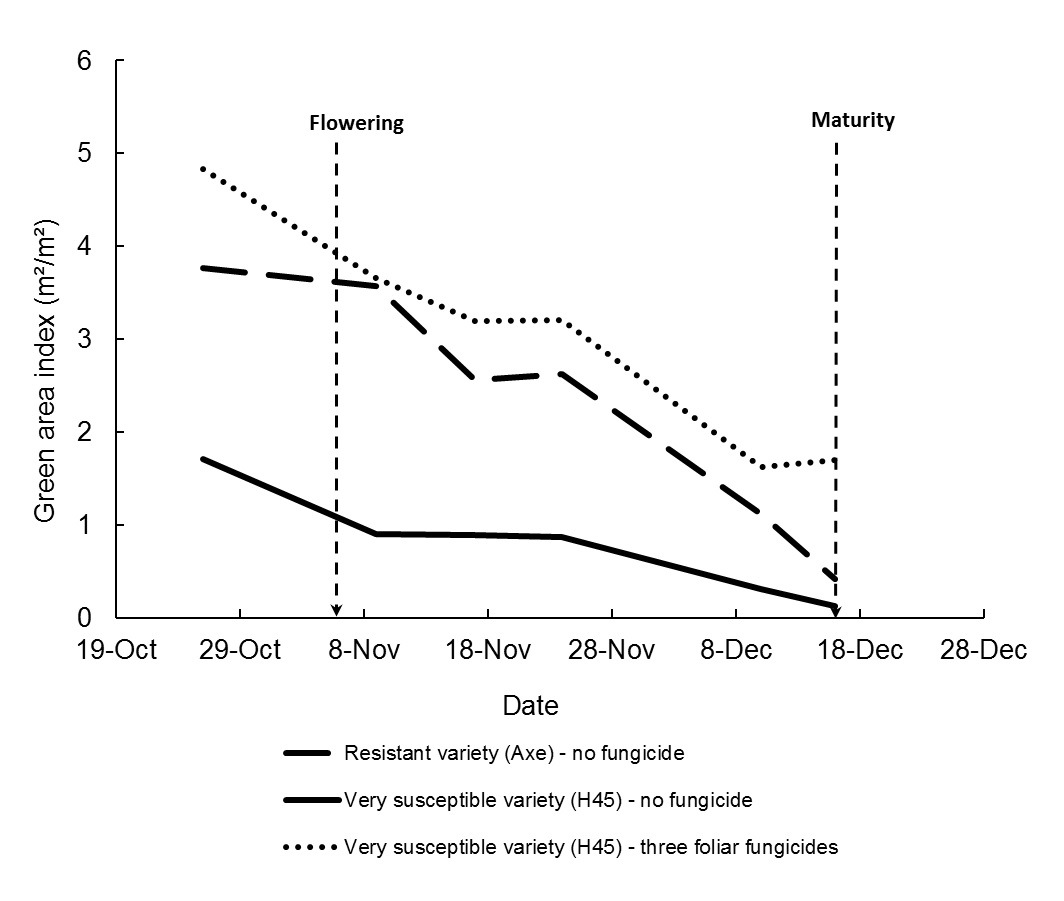

The influence of fungicides as canopy management tools by increasing LAD during grain fill was demonstrated in a trial conducted by CISRO as part of the FAR lead project (SFS00017). The work not only illustrated the influence of a foliar fungicide on green leaf retention and yield but the impact of using a disease resistant cultivar to achieve similar LAD with no fungiciide application (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Influence of fungicide application on Green Area Index (GAI) from ear emergence until maturity.

Septoria tritici blotch (STB)

Combating wheat diseases in the longer season HRZ has changed over the last three seasons. The spectrum of disease in wheat has changed from being dominated by cereal rusts, particularly stripe rust to wet weather necrotrophic diseases such as Septoria tritici blotch (STB) caused by the fungal pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici.

Fungicide strategies that have served growers well for over a decade against cereal rusts do not work as effectively against wet weather diseases such as Septoria tritici blotch (STB). There are two principal reasons for this:

- STB is more difficult to control with foliar fungicides than cereal rusts so generally requires higher rates of fungicide to control it.

- The development of the disease is more difficult to track than stripe rust since it has a longer latent phase (time between spore landing on the leaf and symptoms becoming visible to the grower). This can mean that crops that are incubating the disease tend to stay cleaner for longer before the symptoms become evident.

In addition to these differences with cereal rusts some strains of the STB population in southern Victoria have been found to contain mutations that make them less sensitive to triazole fungicides (Dr A. Milgate NSW DPI). Though the level of insensitivity may not yet be high enough to influence field performance, the continual use of these fungicides (or the same fungicides within the triazole group) against this disease is likely to increase fungicide insensitivity, based on experience in Europe and more recently in New Zealand.

Integrated Disease Management and the need for fungicide mixtures

To combat STB in the future it is imperative that we think of an integrated disease management approach whereby we integrate our knowledge of cultivar resistance, sowing date and fungicides in order to control the disease. This does not mean abandoning the advances that foliar fungicides clearly provide but using them judiciously at application timings that provide maximum benefit. Over the last decade foliar fungicides have fallen in price and fungicides have become a regular additive to the spray tank. The development of fungicide resistance in powdery mildew in WA and the recent discovery of less sensitive strains of STB reminds us of the need to use fungicides wisely and not to over use them. One of the biggest drivers with regard to selecting for fungicide resistance is the number of applications in any one season. In the HRZ it should be possible to control most foliar disease outbreaks with no more than one-two fungicide applications, depending on disease pressure and cultivar resistance.

Importance of fungicide mixtures

In addition to limiting the number of applications it is also important to mix fungicides from different fungicide groups, wherever possible. At present the strobilurin fungicides (azoxystrobin, pyraclostrobin) are the only other fungicide group available to mix with triazoles for control of foliar diseases. In the future it is hoped that Australian growers will have access to foliar fungicides from other fungicide groups such as the SDHI’s (Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors) to combat foliar diseases such as STB. Though both SDHI’s and strobilurins have excellent broad spectrum activity, persistence and green leaf retention properties their value to the grower is also threatened by the development of disease resistance, since both fungicide groups are at higher risk of resistance development than triazoles. Again minimising number of applications and using mixtures with different modes of action is key to protecting these important agrichemicals.

Key timings for fungicide application to wheat in the HRZ

Ultimately fungicide timing should be governed by the presence of the pathogen, however in susceptible cultivars it is difficult to be reactive to foliar disease outbreaks. As a consequence growth stage based fungicide applications allow a greater degree of planning. First fungicide applications ideally need to be applied to coincide with the emergence of flag-2 or flag-1, the two leaves below the flag leaf. The emergence of these leaves generally coincide with the nodal growth stages GS31-33 (first – third node). The second fungicide generally targets the flag leaf, although the exact timing of the flag spray will depend on whether conditions have been conducive for disease since the first application, disease pressure in the crop at the time of the second spray and importantly the exact timing of the first spray. If the first spray was applied at GS33 and the gap is less than two weeks it may be possible to delay the second fungicide until early ear emergence (GS51-53) provided the time interval between the two sprays doesn’t exceed 3-4 weeks. Where the first spray has been applied early, possibly as a result of farm logistics (need to mix with a herbicide), the second spray will have to be brought forward.

Where crops have intermediate ratings for a disease outbreak, consider more flexibility in fungicide timing, particularly between 1st node and flag leaf. Under these circumstances with greater cultivar resistance growers have more time to evaluate the need for a fungicide.

The use of more effective triazole fungicides at flag leaf such as Prosaro® and Opus® or the use of formulated mixtures of triazoles with strobilurins should in the majority of circumstances be sufficient to control disease into grain fill without the need for a specific ear spray in the HRZ.

Barley crops

For barley crops the key focus of foliar fungicide applications for disease control is centred on the start of stem elongation (GS30-31) and the end of booting (GS45-49). For the majority of crops and foliar disease outbreaks experienced in the HRZ, strategies should not require more than one - two fungicide applications. Again where two fungicides are employed the time interval between the sprays should ideally be no more than 3 – 4 weeks.

Contact details

Nick Poole

FAR Australia, 23 High St, Inverleigh

(03) 5265 1290

GRDC Project Code: SFS00017,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK