Oaten hay – its fit in southern New South Wales cropping systems

Oaten hay – its fit in southern New South Wales cropping systems

Author: Peter Matthews (NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange), Felicity Harris, Jennifer Pumpa and Philip Armstrong (NSW Department of Primary Industries, Wagga Wagga). | Date: 18 Feb 2020

Take home messages

- Oaten hay has the potential to be a higher return option than grain-only oat crops in seasons with spring drought conditions.

- Oaten hay production for export markets requires increased agronomic management than domestic hay production or grain-only crops.

Background

Oaten hay production, as part of farming rotations in southern NSW, has focused mainly on domestic markets for the dairy industry and, to a lesser extent, for export. Targeting the export oaten hay market has been seen to have higher production risk compared with the domestic market or alternative grain-only cropping options. Oaten hay production provides growers with risk management tools for frost damage, enterprise mix, and price through a different set of market/price drivers to grain. Other benefits include weed management options, disease management through crop rotation, soil moisture conservation from earlier crop termination, high returns if a quality product is produced, and cash flow management.

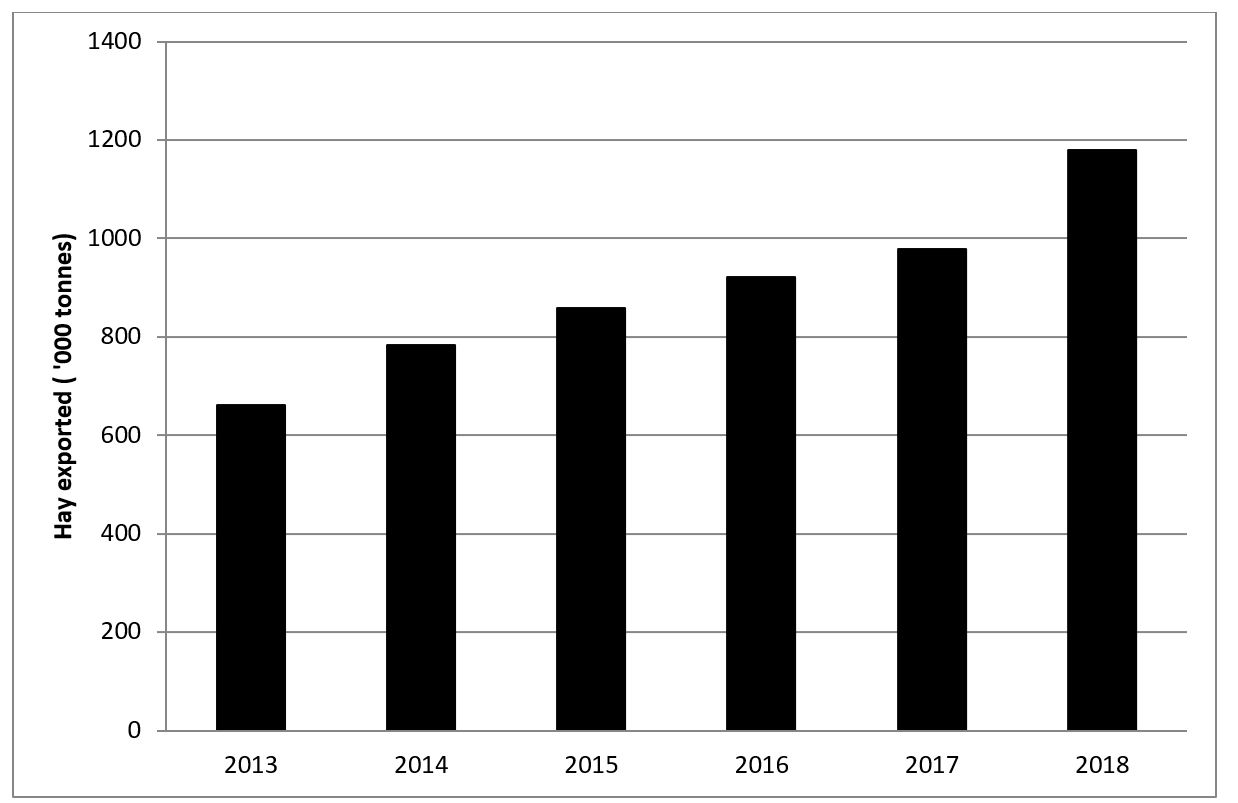

With the increasing world demand for hay from countries such as Japan, China, Taiwan and South Korea, Australian hay exports have continued to increase (Figure 1) and Australian oaten hay is seen as a premium product choice for overseas dairy businesses. This increasing world market now offers NSW growers the opportunity to diversify cropping enterprises and target a high value commodity to improve on-farm returns.

Figure 1. Annual hay exports Australia. Source: Australian Fodder Industry Association 2018 Fodder Conference, Export Fodder Industry Update, M. Patchett.

2019 field experiments

The experiments in NSW are part of a national project on export oaten hay production in partnership with AgriFutures™ Australia. The focus is to demonstrate key management strategies to improve hay yield and maintain hay quality to target the export oaten hay market. Experiments were set up in areas where oaten hay production has been part of the local farming rotations at Yanco, Marrar and Gerogery (Table 1).

Table 1. 2019 field experiments for oaten hay production, NSW

Site | Experiments | |

|---|---|---|

Core research site | Yanco | Sowing date × variety × nitrogen rate Variety × nitrogen timing Variety × plant density |

Regional sites | Marrar | Variety × nitrogen timing Variety × plant density |

Gerogery | Variety × nitrogen timing Variety × plant density | |

All sites recorded below average rainfall for the growing season, with the spring period being well below average (Table 2), combined with periods of high temperatures through early spring.

Table 2. 2019 growing season rainfall from 1 April to 31 October and long-term average for Yanco, Marrar and Gerogery sites.

Site | Growing season rainfall (GSR) (mm) | Long term GSR (mm) |

|---|---|---|

Yanco | 167 | 240 |

Marrar | 194 | 309 |

Gerogery | 276 | 408 |

Results and discussion

As the hay quality results were still being processed at the time of writing, only the biomass (hay yield) and limited physical hay results are included.

Varietal performance

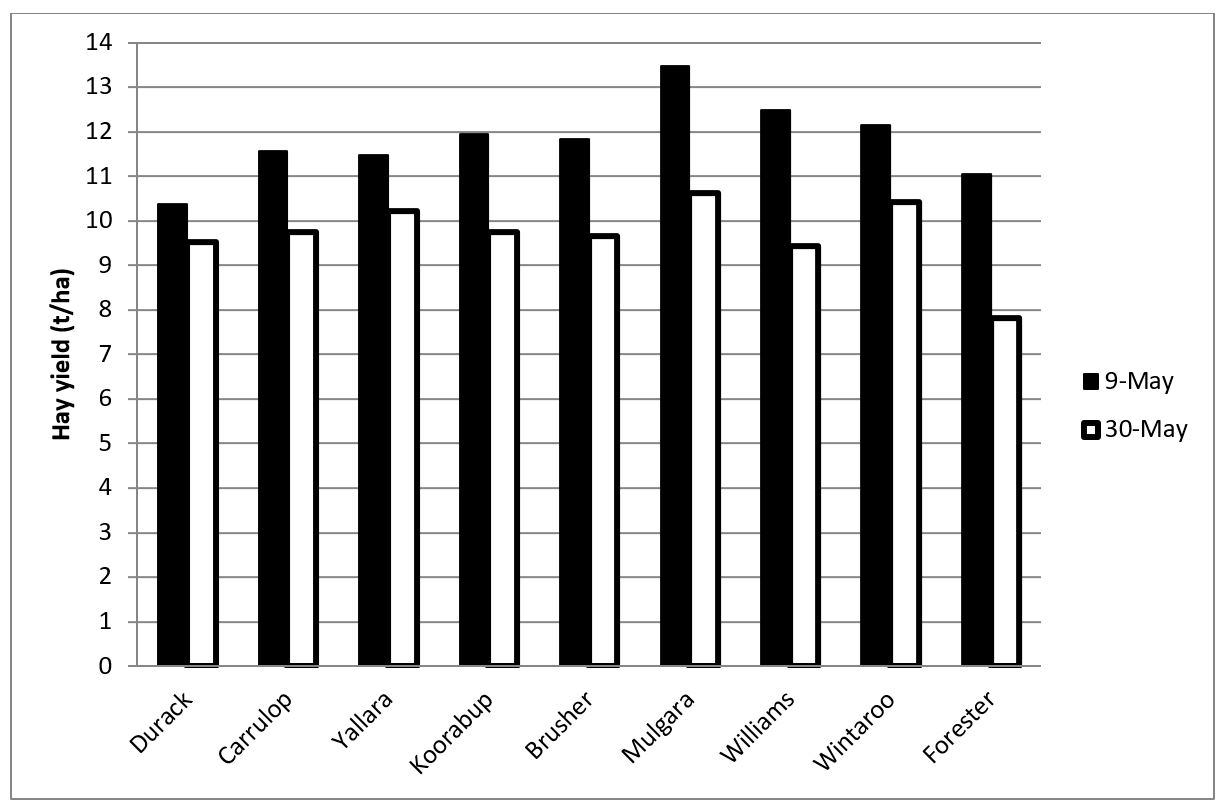

Oaten hay variety performance was variable across the three experiment sites, with rainfall and temperature conditions affecting the varieties’ performance at each site. At Yanco (Figure 2) there was a significant variety × sowing date response, with the later-maturing varieties having a greater drop in hay yield compared with the shorter season varieties such as Durack and Yallara for the 30 May sowing.

Figure 2. Hay yield response to sowing date for oat varieties at Yanco 2019, sown on 9 May and 30 May, Lsd: 0.63.

Variety performance in one year should be viewed with caution, and a variety’s performance compared over several seasons where possible. The national hay oat breeding program based at SARDI has evaluated hay oat performance over several years in southern NSW with Table 3 showing the long-term performance of key varieties.

Table 3. Hay oat variety long-term performance (2014–2018) (source SARDI National Oat Breeding program) (tonnes/ha)

Variety | Maturity | NSW | SA | Vic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Koorabup | Early-mid–mid | 8.5 | 11.3 | 8.1 |

Brusher | Early-mid | 8.9 | 12 | 8.3 |

Durack | Very early | 9.0 | 11.7 | 7.7 |

Mulgara | Early-mid | 8.9 | 11.8 | 8.3 |

Wintaroo | Mid | 9.2 | 12.3 | 8.8 |

Yallara | Early | 9.1 | 12.4 | 8.5 |

No. sites | 4 | 12 | 9 |

Hay yield response to nitrogen

There were no significant responses to nitrogen treatments at any of the experiment sites for hay yield, with the extremely dry spring conditions limiting the response to both nitrogen rates and application timing.

Plant density

The dry season and hot temperatures in spring impacted on the plants’ ability to respond to different plant densities, with no significant response to increasing plant density recorded at Yanco, Marrar and Gerogery for hay yield. Differences in plant tiller numbers were recorded at Yanco and Marrar, but this did not translate to higher hay yields later in the season.

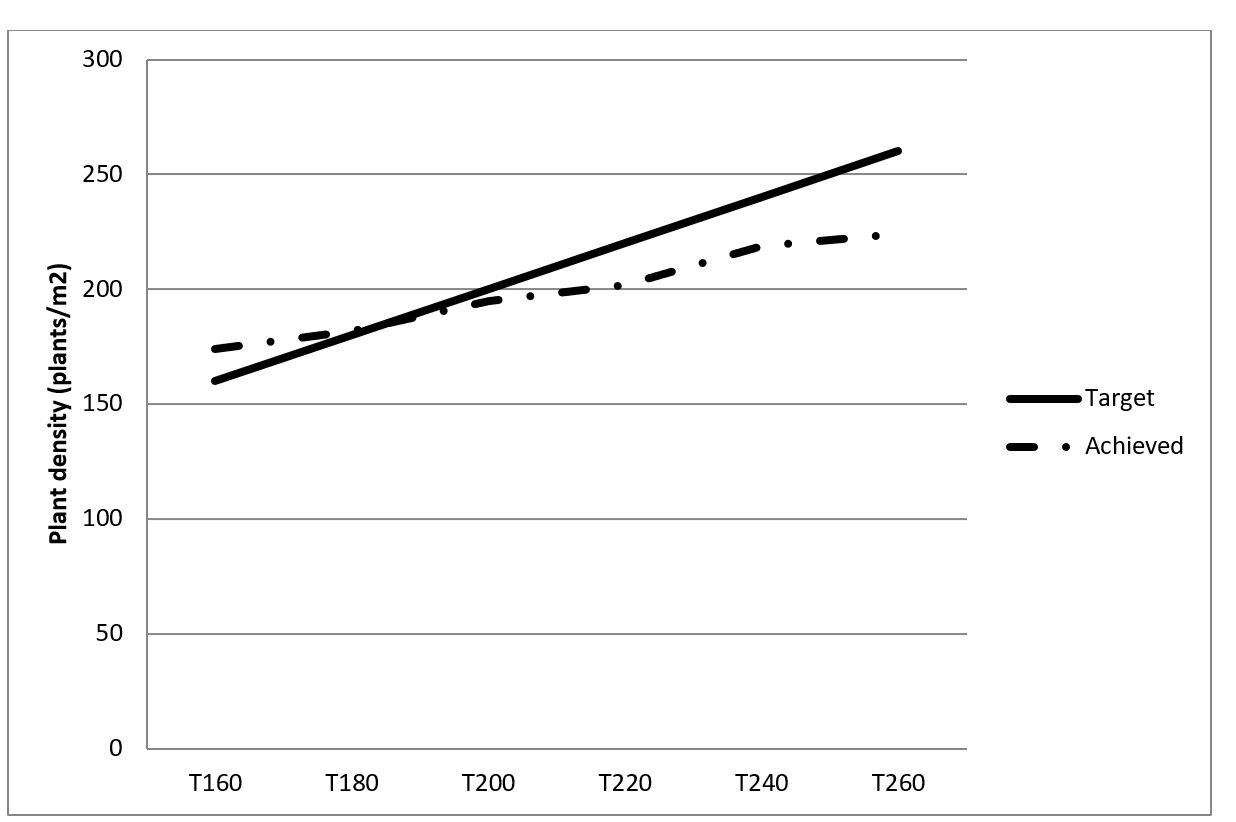

The target plant densities for oaten hay production are higher compared with grain only production, with two to three times the plant densities targeted to improve hay quality by reducing stem thickness. Plant densities for hay production in Western Australia and South Australia are above 300plants/m2. When targeting high plant densities, reduced establishment percentages were apparent, due to inter-seed/plant competition in the plant row (Figure 3). This inter-row competition increases in importance when sowing on wider rows, as more plants are compressed into fewer rows. Therefore, seeding rates need to be adjusted upwards, or row spacing reduced by double sowing (two passes) the paddock.

Figure 3. Achieved oaten hay plant density versus target plant density at Marrar in 2019.

Hay colour

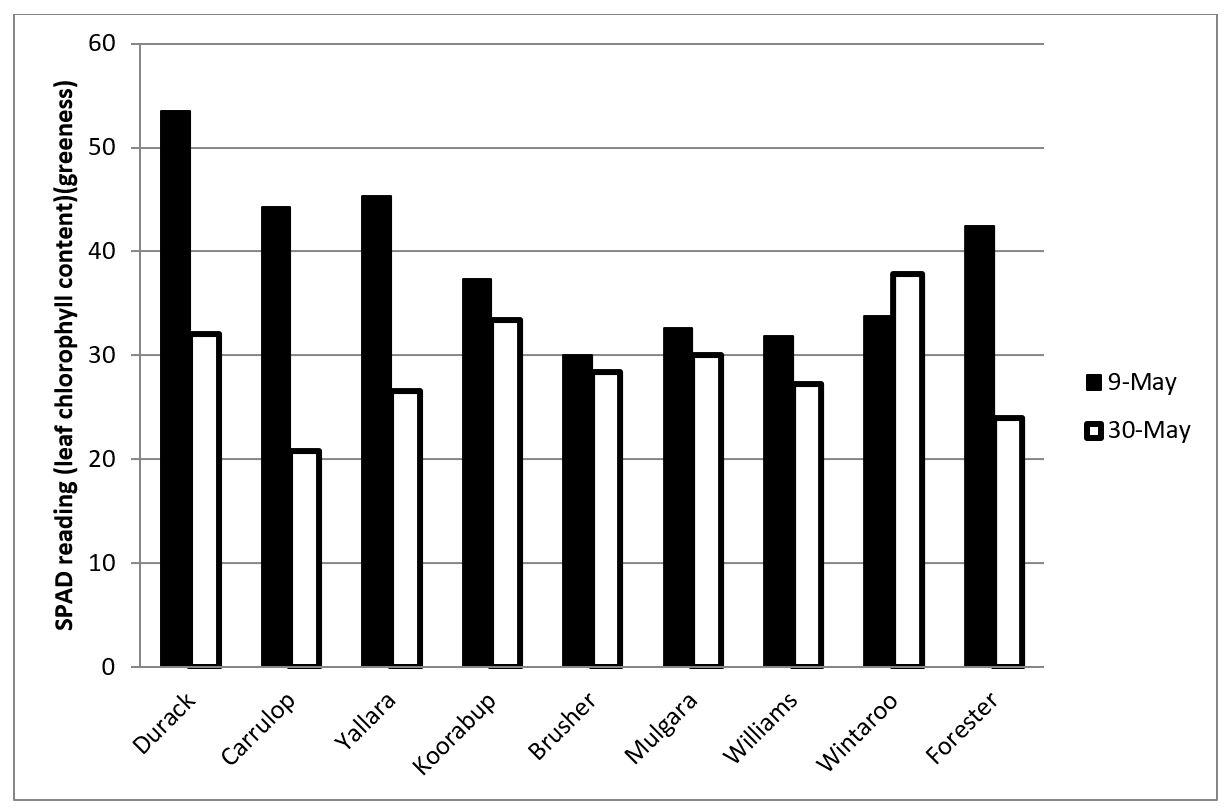

Hay colour was measured using a SPAD meter, which measures leaf chlorophyll concentration. There was a significant colour change between varieties and sowing dates, with an interaction observed between variety and sowing date for greenness (Figure 4). Nitrogen rates also had an impact with a significant response to increasing nitrogen rates, shown in Table 4.

Figure 4. SPAD reading (greenness) response to sowing date for oat varieties at Yanco 2019, sown on 9 May and 30 May, Lsd: 5.23.

Table 4. SPAD reading (greenness) response to nitrogen rate for hay oats at Yanco 2019.

Nitrogen treatment (kgN/ha) | SPAD reading (greenness) # |

|---|---|

30 | 33.19 a |

60 | 33.99 ab |

90 | 34.74 b |

Lsd | 0.939 |

# different letters denote significant differences between results.

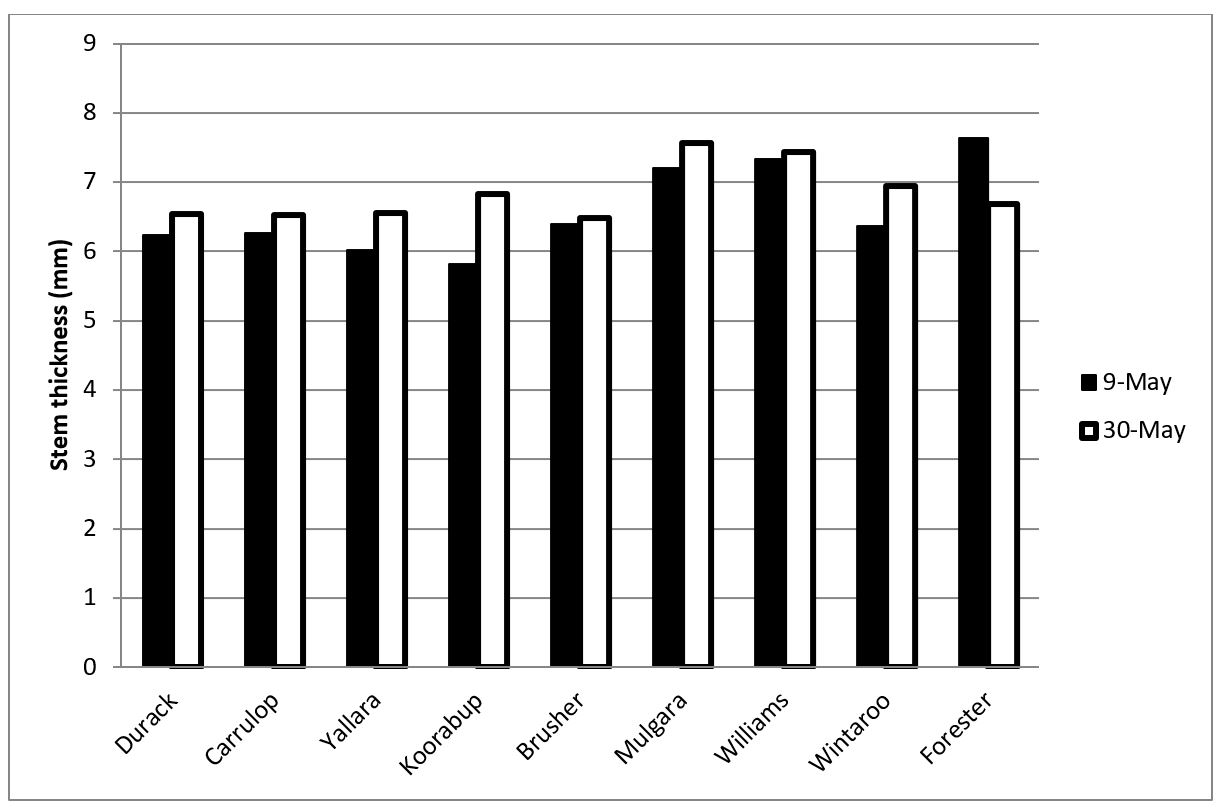

Stem thickness

Hay stem thickness increased at Yanco when sowing date was delayed, with the exception of the very late maturing variety, Forester, with a significant response for variety × sowing date for stem thickness. Stem thickness is seen to influence digestibility and potential lignin content (undigestable component of feed) in the hay, affecting animal performance. The market also associates smaller stem thickness with a stock feeding preference, which can influence animal intake.

Figure 5. Stem thickness response to sowing date for oat varieties at Yanco 2019, sown on 9 May and 30 May, Lsd : 0.245.

Hay versus grain production

The direct comparison between oaten hay and grain production was not part of the aims of the experiments, however, a comparison between the oaten hay experiments and an adjoining National Variety Trail (NVT) oat variety experiment at Gerogery shows what the potential for hay was compared with grain production in the dry season of 2019 (Table 5).

Table 5. Grain and hay yield comparison from a hay experiment co-located with an NVT oat trial at Gerogery in 2019.

Variety | NVT oat trial Grain yield (tonnes/ha) | Hay oat trial Hay yield (tonnes/ha) |

|---|---|---|

Durack | 2.19 | - |

Bilby | 1.96 | - |

Kowari | 1.88 | - |

Mitika | 1.59 | - |

Bannister | 1.58 | - |

Yallara | 1.44 | 8.47 |

Williams | 1.40 | 8.12 |

Koorabup | 1.15 | - |

Lsd | 0.25 | 0.48 |

Note: Lsd can only be compared within trial. | ||

Conclusion

Oaten hay production is an option for growers in southern NSW and provides growers with a high-yielding alternative to grain crops and, if managed properly, the opportunity to capitalise on export hay prices. The 2019 season was a difficult season with the dry finish masking many of the potential differences within the experiments. However, the results still highlighted the importance of adopting different crop agronomy and management to grain crops — if growers are aiming to achieve high hay yields and meet the required hay quality parameters (such as hay colour and stem diameter) that the hay industry demands.

Useful resources

Winter Crop Variety Sowing Guide_ NSW DPI

Producing Quality Oat Hay_AEXCO

NVT online- results and reports

References

Patchett, M., (2018) Export Fodder Industry Update, Australian Fodder Industry Association 2018 Fodder Conference.

Hoppo, S. and Zwer, P. (2019) Oat Breeding Newsletter November 2019, SARDI.

Acknowledgements

A sincere thank you for the technical assistance of Fiona Bennet, Lorraine Thacker, Kirra Hubbard and Emma Angove at the Gerogery and Yanco sites and hay quality sample processing. Cameron Copeland, Dean Maccallum, Mary Matthews, Jessica Simpson, Ian Menz, Bren Wilson and Javier Atayde at the Marrar site and Tony Napier, Daniel Johnston and Reuben Burrough at the Yanco site.

We also acknowledge the support and cooperation of the Pattison family at Marrar, the Moll family at Gerogery and NSW DPI at the Yanco Agricultural Institute.

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the contributions of growers and industry through the support of AgriFutures™ Australia, NSW Department of Primary Industries, WA Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD), South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI) and Agriculture Victoria. The authors would like to thank them for their support.

Contact details

Peter Matthews, Technical Specialist, Grain Services

NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange

02 63913198

peter.matthews@dpi.nsw.gov.au