Implications of continuing dry conditions on cereal disease management

Author: Steven Simpfendorfer (NSW DPI) | Date: 04 Mar 2020

Take home messages

- Due to a combination of factors there is likely to be increased cereal plantings in 2020, once the opportunity arises

- Failed pastures with decent levels of grass development are potentially high risk scenarios for cereal diseases in 2020 as grasses host many of the causal pathogens

- Unfortunately, prolonged dry conditions increase the risk of cereal diseases including Fusarium crown rot and common root rot

- There has also been a decline in populations of beneficial arbuscular mycorrhizae fungi (AMF)

- However, steps can be taken to minimise impacts which include:

1. Know before you sow (e.g. PREDICTA®B)

2. Implementing pre-sowing management options

3. Sowing quality seed known to have both good germination and vigour

4. Assessing root health and infection levels around heading – you need to ‘dig deeper’ than just leaf diseases!

Introduction

Unfortunately much of northern NSW and southern Qld experienced a relatively dry winter cropping season again in 2019. These conditions, especially with hotter and drier conditions during grain filling, are ideal for the expression of Fusarium crown rot as whiteheads and resulting yield loss. Fusarium crown rot, caused predominantly by the stubble-borne fungus Fusarium pseudograminearum, infects all winter cereal crops (wheat, barley, durum, triticale and oats) and numerous grass weed species also host this pathogen. However, a key point is that dry conditions do not just have implications for Fusarium crown rot management. There are other potential cereal disease implications that need to be considered by growers and management strategies implemented to maximise profitability when recovering from drought.

Potential consequences of dry conditions

Extended dry conditions in 2018 and 2019, possibly longer in some areas, has a range of potential implications on farming systems which can include:

- Reduce stubble cover – increasing wind erosion, reducing fallow efficiency and limiting stored soil moisture levels

- Reduced decomposition of crop residues which can extend inoculum survival to 2 to 4+ years

- Reduced animal stock numbers – extended dry has seen sheep and cattle numbers decline which will take a number of seasons to recover

- Reduced survival of pastures in mixed cropping systems

- Later seasonal breaks reducing opportunities for canola establishment in some districts

- Widespread baling of cereal crops for hay in 2018 and 2019

- Increased pressure on available planting seed for establishing crops in 2020.

Although many of these issues are common across continuous and mixed cropping enterprises, as a general rule those operations that have opted for more intensive broad acre crop production are hopefully more aware of potential pitfalls around limiting cereal diseases and ensuring quality of planting seed. The lack of animal stock, failure of pastures and need for ground cover is likely to see a substantial increase in the area of cereals planted, especially in mixed farming systems once the drought breaks. Grass species and grass weeds tend to dominate as legume species decline in pasture mixes over time and with moisture stress. These are therefore potentially higher risk paddocks for cereal diseases as the grasses serve as alternate hosts for pathogens such as Fusarium pseudograminearum (Fusarium crown rot), Bipolaris sorokiniana (common root rot), Rhizoctonia solani (rhizoctonia root rot), Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici (take-all), root lesion nematodes and some leaf diseases (e.g. barley grass hosts net-blotch pathogen Pyrenophora teres).

When the drought does break in impacted regions, hopefully in 2020, growers will be driven by two key factors. The first will be to generate cash flow and the second will be to restore groundcover to bare paddocks through the planting of winter cereals. This will potentially occur with little regard to the risk posed by plant pathogens and the quality of available planting seed. Maximising the profitability of crop production is going to be critical to many farming operations once the drought breaks. The following paper highlights some of the potential issues for consideration by growers and agronomists from a cereal pathology view point. Some practical steps that can be taken to hopefully minimise losses are also outlined.

Step 1: Know before you sow

Although paddock history can be a good guide to potential disease issues, extended dry conditions can allow damaging inoculum levels to still persist from 2-4+ seasons ago (Table 1). Hence, growers need to consider the longer-term sequences within paddocks. How cereal stubble was handled over prolonged dry conditions can also influence the survival and distribution of cereal pathogens. Paddock history is only a guide and provides no quantitative information on the actual level of risk posed by different cereal diseases.

Table 1. Decline in pathogen and beneficial arbuscular mycorrhizae fungi (AMF) levels over 20 months in a replicated cereal variety experiment at Rowena

Pathogen | 13 Dec 2017 | 12 June 2019 | % decline | Risk mid-2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Prat. Thornei (no./g soil) | 7.7 | 4.3 | 44 | Medium |

Common root rot (pgDNA/g) | 58 | 38 | 35 | Low-medium |

Crown rot (phDNA/g) | 579 | 256 | 56 | High |

AMF (KDNA copies/g) | 90 | 55 | 39 | Adequate |

Consider testing paddocks using PREDICTA®B. This would be especially useful for paddocks coming out of failed pastures which may have become dominated by grasses. PREDICTA®B is a quantitative DNA based soil test which provides relative risk or population levels for a wide range of pathogens that can be used to guide management decisions. However, ensure you are using the latest recommended PREDICTA®B sampling strategy which includes the addition of cereal stubble to soil samples (see useful resources). Addition of cereal stubble (or grass weed residues if present in pasture paddocks) improves detection of stubble-borne pathogens which cause diseases such as Fusarium crown rot, common root rot, yellow spot in wheat and net-blotches in barley. Considerable GRDC co-funded research has been conducted nationally over the last 5 years to improve the recommended sampling strategy, refine risk categories and include additional pathogens or beneficial fungi (AMF) on testing panels. Recent paddock surveys have highlighted that a single pathogen rarely exists in isolation within individual paddocks, but rather multiple pathogens occur in various combinations and at different levels. PREDICTA®B is world leading technology that can quantitatively measure these pathogen combinations within a single soil + stubble sample. Given extended dry conditions the two key cereal diseases of concern for 2020 in northern NSW and southern Qld are likely to be Fusarium crown rot and common root rot. Decline in beneficial AMF populations is also of concern. The risk of both of these diseases and AMF populations can all be determined by PREDICTA®B.

Alternately, cereal stubble or grass weed residues can be collected from paddocks and submitted to NSW DPI laboratories in Tamworth as a ‘no charge’ diagnostic sample (see contact details). Samples are plated for recovery of only two pathogens which cause Fusarium crown rot or common root rot and provide no indication of other potential disease risks.

Step 2: Consider pre-sowing management options

Generic management options are provided with PREDICTA®B test results which are tailored to the actual levels of different key pathogens detected within a sample. Your PREDICTA®B accredited agronomist should also be able to assist with interpretation which can be daunting given the number of pathogens covered by the testing. NSWDPI are also happy to discuss results (PREDICTA®B or stubble testing) and work through potential management options (see contact details).

Fusarium crown rot (Fusarium pseudograminearum)

Assuming the main concern is Fusarium crown rot. Based on the following PREDICTA®B or stubble test results, pre-sowing management options include:

Below detection limit (BDL) or low:

No restrictions, ensure good crop agronomy

Medium:

Consider sowing a non-host pulse or oilseed crop with good grass weed control.

If sowing cereal then:

- Avoid susceptible wheat or barley varieties, durum is higher risk but oats are fine

- Sow at the start of a varieties recommended window for your region

- Consider inter-row sowing (if previous cereal rows are still intact) to limit contact with inoculum

- Do not cultivate - it will spread inoculum more evenly across the paddock and into infection zones below ground

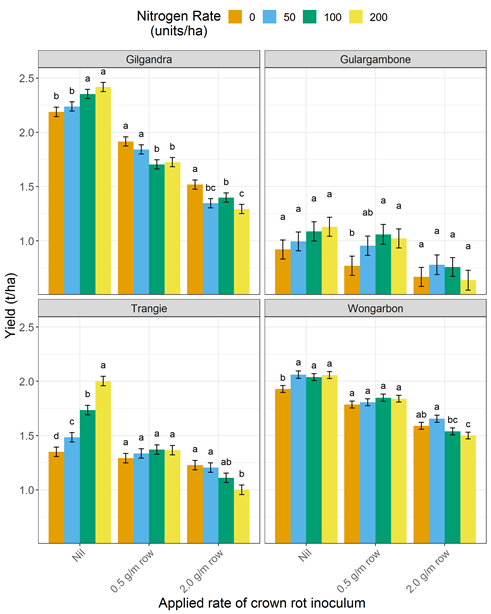

- Be conservative on nitrogen application at sowing (Figure 1) as this can exacerbate infection (e.g. consider split application) but ensure a maintenance level of zinc is applied

- Be aware that current seed treatments registered for Fusarium crown rot suppression provide limited control

- Determine infection levels around heading (see step 4).

High:

Consider sowing a non-host pulse or oilseed crop with good grass weed control.

If sowing cereal then:

- Choose a more tolerant wheat or barley variety for your region to maximise yield and profit (Table 2), durum is very high risk with yield loss >50% are probable in a tough finish but oats are still a decent option

- Sow at the start of a varieties recommended window for your region as this can half the extent of yield loss

- If a late break occurs consider switching to a quicker maturing wheat variety or go with barley to limit exposure to heat stress during grain filling which exacerbates yield loss

- Consider inter-row sowing (if previous cereal rows are still intact) to limit contact with inoculum

- Do not cultivate - it will spread inoculum more evenly across the paddock and into infection zones below ground

- Be conservative on nitrogen application at sowing (Figure 1) as this can exacerbate infection (e.g. consider split application) but ensure a maintenance level of zinc is applied

- Be aware that current seed treatments registered for Fusarium crown rot suppression provide limited control and get to a Syngenta learning centre in 2020

- Determine infection levels around heading (see step 4) and be prepared from sowing to cut for hay or silage if required.

Figure 1. Interaction of nitrogen nutrition and crown rot infection on bread wheat (Suntop and EGA Gregory) yield across four sites in central NSW in 2018. Note: Nil applied inoculum represents a BDL/low risk, 0.5 g/m row a medium risk and 2.0 g/m row a high risk of crown rot infection.

Figure 1. Interaction of nitrogen nutrition and crown rot infection on bread wheat (Suntop and EGA Gregory) yield across four sites in central NSW in 2018. Note: Nil applied inoculum represents a BDL/low risk, 0.5 g/m row a medium risk and 2.0 g/m row a high risk of crown rot infection.

Table 1. Average yield (t/ha), yield loss from crown rot (%), screenings (%) and lost income from crown rot ($/ha) of four barley, 5 durum and 20 bread wheat entries in the absence (no added CR) and presence (added CR) of crown rot inoculum averaged across 50 sites in central/northern NSW and southern Qld – 2013 to 2017.

Varieties within crop species ordered from highest to lowest yield in added CR treatment. Lost income and income in added CR treatment based solely on reduced yield (t/ha) in added CR treatment or absolute yield (t/ha) in this treatment multiplied by average grain price of $220/t for barley, $240 for AH and $300/t for APH bread wheat and $350/t for durum. Grain quality impacts and variable costs including PBR not considered.

Crop | Variety | Quality | Yield (t/ha) | Yield loss | Screenings | Lost income from crown rot | Income added CR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| No added CR | Added CR | (%) | No added CR | Added CR | ($/ha) | ($/ha) | |

Barley | La Trobe | 4.17 | 3.59 | 14.0 | 6.5 | 8.4 | 128 | 790 | |

| Spartacus | 4.18 | 3.58 | 14.3 | 2.9 | 4.6 | 131 | 788 | |

| Commander | 4.09 | 3.40 | 16.8 | 6.1 | 8.2 | 151 | 748 | |

| Compass | 4.20 | 3.39 | 19.4 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 179 | 745 | |

Durum | Lillaroi | 3.79 | 3.00 | 20.8 | 3.2 | 5.9 | 275 | 1050 | |

| Bindaroi | 3.88 | 2.92 | 24.7 | 2.7 | 5.8 | 336 | 1023 | |

| Jandaroi | 3.48 | 2.64 | 24.3 | 4.1 | 9.2 | 296 | 923 | |

| Caparoi | 3.34 | 2.20 | 34.1 | 9.0 | 16.5 | 399 | 770 | |

| AGD043 | 2.72 | 1.65 | 39.1 | 3.8 | 13.8 | 372 | 579 | |

Bread | Beckom | AH | 4.57 | 3.94 | 13.9 | 8.8 | 12.7 | 153 | 944 |

wheat | Mustang | APH | 4.17 | 3.67 | 11.9 | 5.2 | 7.0 | 148 | 1102 |

| Mitch | AH | 4.08 | 3.51 | 13.9 | 7.7 | 10.2 | 136 | 842 |

| Reliant | APH | 4.18 | 3.50 | 16.3 | 5.3 | 8.1 | 204 | 1051 |

| Suntop | APH | 3.99 | 3.46 | 13.3 | 7.3 | 9.6 | 160 | 1037 |

| Sunguard | AH | 3.81 | 3.35 | 12.0 | 6.2 | 8.7 | 110 | 804 |

| Spitfire | APH | 3.86 | 3.34 | 13.3 | 5.8 | 8.0 | 154 | 1003 |

| Gauntlet | APH | 3.92 | 3.29 | 16.1 | 4.4 | 7.0 | 189 | 987 |

| Lancer | APH | 3.88 | 3.27 | 15.8 | 4.8 | 7.1 | 184 | 981 |

| Sunmate | APH | 4.02 | 3.23 | 19.6 | 6.4 | 9.7 | 237 | 969 |

| Coolah | APH | 4.03 | 3.21 | 20.4 | 5.8 | 9.4 | 247 | 962 |

| Flanker | APH | 4.04 | 3.12 | 22.8 | 6.0 | 10.4 | 277 | 936 |

| Dart | APH | 3.73 | 2.99 | 19.9 | 9.3 | 12.8 | 223 | 897 |

| EGA Gregory | APH | 3.90 | 2.89 | 25.9 | 6.7 | 11.4 | 303 | 868 |

| Viking | APH | 3.48 | 2.89 | 17.1 | 10.9 | 16.8 | 179 | 866 |

| Lincoln | AH | 3.88 | 2.78 | 28.3 | 8.6 | 12.8 | 264 | 668 |

| Crusader | APH | 3.43 | 2.76 | 19.4 | 8.3 | 13.4 | 199 | 829 |

| QT15064R | APH | 3.68 | 2.73 | 25.7 | 8.3 | 15.1 | 284 | 819 |

| Suntime | APH | 3.43 | 2.62 | 23.6 | 10.6 | 17.2 | 243 | 787 |

| Strzelecki | AH | 3.03 | 2.17 | 28.3 | 12.0 | 18.0 | 206 | 521 |

|

| Lsd (P=0.05) | max. 0.137 | max. 1.37 | |||||

Note: The extent of yield loss associated with crown rot infection varied between seasons and sites being 21% in 2013 (range 13% to 55% across nine sites), 22% in 2014 (range 6% to 47% across 12 sites), 18% in 2015 (range 7% to 42% across 12 sites), 13% in 2016 (range 6% to 29% across 11 sites) and 29% in 2017 (range 20% to 45% across six sites) averaged across varieties.

Common root rot (Bipolaris sorokiniaina)

The trend to deeper and earlier sowing of cereals into warmer soils is associated with an increased prevalence of common root rot(CRR) across Australia, especially in the northern region. Deeper sowing lengthens the sub-crown internode in cereals which increases susceptibility to CRR. Soil temperatures greater than 20-30°C, which often occur when sowing earlier, also favour Bipolaris infection with yield losses between 7% and 24% reported from CRR in bread wheat. However, delaying sowing to reduce CRR levels is not recommended as the negative impact on yield potential generally outweighs the impact of increased CRR. Note that CRR is also frequently found in association with crown rot, exacerbating yield loss.

Assuming the main concern is common root rot (CRR). Based on the following PREDICTA®B test results pre-sowing management options include:

Below detection or low:

No restrictions, ensure good crop agronomy

Medium or high:

Consider sowing a non-host pulse or oilseed crop with good grass weed control.

If sowing a cereal then:

- Grow partially resistant wheat or barley varieties, oats and triticale may not develop severe infection but act as hosts

- Consider increasing sowing rate to compensate for potential tiller losses

- Consider inter-row sowing (if previous cereal rows are still intact) to slightly reduce infection levels

- If moisture permits, reduce sowing depth to limit the length of the sub-crown internode which is the primary point of infection

- Ensure good phosphorus nutrition which reduces severity

- Ensure good nitrogen nutrition as stunting and lack of vigour is more pronounced in paddocks that are N deficient

- Assess root health coming into Spring (see step 4).

Arbuscular mycorrhizae fungi (AMF)

AMF colonise roots of host plants and develop a hyphal network in soil which reputedly assists the plant to access phosphorus and zinc. Low levels of AMF have been associated with long fallow disorder in dependent summer (cotton, sunflower, mungbean and maize) and winter crops (linseed, chickpea and faba beans). Although wheat and barley are considered to be low and very low AMF dependent crops respectively, they are hosts and are generally recommended to grow to elevate AMF populations prior to sowing more AMF dependent crop species. PREDICTA®B has two DNA assays for AMF and it is important to remember that in contrast to all the other pathogen assays, AMF is a beneficial so nil or low DNA levels are the actual concern. It is concerning that AMF DNA was not detected in root systems of 39% of 150 cereal crops surveyed in central/northern NSW and southern Qld in 2018 (Simpfendorfer and McKay 2019). AMF levels are likely to have declined further in the northern region with continued dry conditions in 2019 (Table 1).

Based on the following PREDICTA®B test results (combining the two AMF test results) pre-sowing management options include (Chapter 10: Broadacre Soilborne Disease Manual, SARDI):

Low (<10; long fallow disorder risk high):

- Consider growing winter cereals which are a host but have low AMF dependency to increase population

- Avoid sowing highly dependent crops (e.g. chickpea, faba bean, sunflower, mungbean, maize)

- Do not burn stubble.

Medium (10<20):

- Avoid sowing highly dependent crops (e.g. chickpea, faba bean, sunflower, mungbean, maize) if phosphorus levels are low, including at depth

- Avoid burning stubble.

High (>20):

- Crop choice not restricted – be aware canola, lupins and long fallow will reduce AMF levels

- Grow most profitable crop.

Step 3: Ensure quality of planting seed

Seed retained for sowing is a highly valuable asset and the way it was treated at harvest and in on-farm storage during summer, or between seasons, is critical to ensure optimum germination potential and crop establishment in 2020. Retained seed can be tested for vigour, germination, purity/weed seeds and disease pathogens. It is advisable to undertake testing at least two months before sowing so that an alternate seed source can be organised if required. Grading to remove smaller grains which inherently have reduced vigour can also improve the quality of planting seed.

Vigour and germination tests provide an indication of the proportion of seeds that will produce normal seedlings and this helps to determine seeding rates. Particular attention should be given to determining vigour of retained seed for sowing in 2020 due to seasonal conditions in 2018-19. Vigour will be even more important if growers plan to increase sowing depth to capture an earlier sowing opportunity through moisture seeking.

NSW DPI, Tamworth normally provides pathology testing of winter cereal seed for common seed-borne fungal pathogens which will continue in 2020. Germination is also noted but this only tells growers how much of their seed is alive with the main purpose of testing to determine levels of fungal infection present. Testing will be extended for the 2020 pre-season to also provide an indication of vigour and emergence which should be used as a guide only (see contact details).

A comprehensive GRDC fact sheet outlining issues with retaining seed after challenging seasons is available from the GRDC website (see useful resources). The fact sheet outlines how growers can test their own seed. Alternatively, a range of commercially accredited providers of both germination and vigour tests are available.

Seed treatments containing fluquinconazole, flutriafol or triadimenol, can reduce coleoptile length in cereals and cause emergence issues under certain conditions. These active ingredients should be avoided if sowing seed with potentially lower vigour, sowing deeper, sowing into cooler soils, in soils prone to surface crusting or where herbicides such as trifluralin have been applied.

Step 4: Assess infection levels and root health prior to head emergence

Common root rot does not cause distinct symptoms in the paddock. Infected cereal crops may lack vigour and severe infections can lead to stunting of plants and a reduction in tillering. These general symptoms of ‘ill-thrift’ in CRR infected wheat and barley crops can often go undiagnosed. This can be easily identified with the help of a shovel or spade! Simply dig up some plants around heading, wash soil away from roots and inspect the general root health paying particular attention to whether the sub-crown internode (joins seed to the crown) has partial or whole dark brown to black discolouration.

This is a very similar to the situation with Fusarium crown rot, which can also go unnoticed in paddocks until dry and hot conditions during grain filling trigger the expression of conspicuous whiteheads. However, honey-brown discolouration at the base of infected tillers can be used to determine the extent of Fusarium crown rot infection prior to heading. Simply dig up plants (inspect root health at the same time as above), ensure leaf sheathes at the base of tillers are removed and visually inspect for brown discolouration.

Assessing root health and Fusarium crown rot infection levels around heading allows a grower to make an informed decision at this point in time given seasonal predictions (e.g. cutting for hay or silage, reduce further input costs) rather than simply letting the weather dictate the outcome. Although this would be a less than an ideal situation, such tough decisions can still maximise profitability or minimise losses under these scenarios.

Other potential implications of dry conditions – learnings from north NSW in 2019

Dry conditions can also impact on the lifecycle of necrotrophic fungi which cause yellow spot in wheat or net-blotches in barley. We observed this around Croppa Creek in northern NSW in 2019 with spot form of net-blotch (SFNB) in barley crops. Numerous barley crops in a restricted area had decent levels of SFNB lesions on leaves during tillering. This was surprising as the season was relatively dry up to this point with only low rainfall events (<5 mm) since sowing. Rainfall events were accompanied by early morning fogs. These conditions, while not really contributing to yield potential, were enough to meet the 6 hours of high humidity (>80% RH) to initiate SFNB infections on leaves. Interestingly, due to dry conditions the primary infection propagules (pseudothecia) which have a moisture requirement had not matured on 2018 barley stubble. The primary source of infection was mature pseudothecia present on 2017 or even 2016 barley stubble. SFNB was also present in two barley crops sown into wheat stubble which was surprising. However, conidia of the net-blotch fungus Pyrenophora teres formed on collected wheat stubble after 4 days in humid chambers. This supports 2018 disease survey findings where the SFNB fungus was found to be saprophytically infecting wheat crops due to late rainfall in October coinciding with senescence of lower wheat leaves.

High levels of SFNB were also present in two barley crops in this same region in 2019 where seed was treated with the fungicide Systiva ®. Reduced sensitivity to this SDHI active (fluxapyroxad) was confirmed by the Curtin University fungicide resistance group in net form of net-blotch (NFNB) populations on the Yorke Peninsula of SA in 2019. Pure SFNB isolates collected from these northern NSW barley crops were sent to Curtin University and shown to have no reduced sensitivity to fluxapyroxad. In our situation we suspect that dry conditions around the seed prevented Systiva® from dissolving into the surrounding soil, limiting uptake through the roots and movement through the plant into leaves. Seedlings had established well and their root systems had penetrated into deeper soil moisture which was allowing them to progress, but the top 10 cm of soil was very dry with little visual loss of red pigmentation from the seed treatment on seed coats at the time of inspection.

Conclusions

The perpetual risk as a plant pathologist is the perception that we are always the bearer of bad news or ‘of the grim reaper mentality’. Elevated risk of stubble- and soil-borne diseases in 2020 is inevitable given continuing dry conditions which have prolonged survival of pathogen inoculum. However, practical steps can be taken to identify the level of risk and strategies implemented to minimise but not necessarily fully eliminate disease impacts on wheat and barley crops in 2020. Hopefully wet conditions restrict impact of Fusarium crown rot. However, growers and their agronomists need to be prepared to inspect the root health and stem bases of cereal crops around heading to guide some potentially tough but informed decisions. NSW DPI plant pathologists are also available throughout the season to provide support.

Useful resources

Correct sampling 'a must' to accurately expose disease risk - Groundcover supplement

Simpfendorfer S, McKay A (2019). What pathogens were detected in central and northern cereal crops in 2018? GRDC Update, Goondiwindi.

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support. The author would also like to acknowledge the ongoing support for northern pathology capacity by NSW DPI.

Contact details

Steven Simpfendorfer

NSW DPI, 4 Marsden Park Rd,

Tamworth, NSW 2340

Ph: 0439 581 672

Email: steven.simpfendorfer@dpi.nsw.gov.au

® Registered trademark

PREDICTA is a registered trademark of Bayer.

Varieties displaying this symbol beside them are protected under the Plant Breeders Rights Act 1994.

GRDC Project Code: DAN00213,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK