Diseases in pulses and canola – the watchouts and implications for 2021

Diseases in pulses and canola – the watchouts and implications for 2021

Author: Kurt Lindbeck (NSW DPI), Ian Menz (NSW DPI) and Steve Marcroft (Marcroft Grains Pathology) | Date: 16 Feb 2021

Take home messages

- Changes in farming practice in the last 15 years have increased disease pressure on cropping rotations in southern NSW

- In 2020, exceptional conditions for crop production also increased the incidence and severity of disease in broadleaf crops in the region. This will have implications for disease management in crops in 2021

- Annual crop surveys are an important means of monitoring disease incidence and severity between districts and between years. Surveys enable the identification of emerging disease issues and forewarning of potential problems

- Sclerotinia diseases were widespread in broadleaf crops across the region in 2020, especially narrowleaf lupin and canola. This will have implications in 2021 and beyond

- Blackleg was observed in every canola crop assessed as part of the IDM crop survey

- Canola sown into a double break scenario will potentially require pre-emptive management to minimise disease risk

- The decision to use fungicides is not always clear and should be assessed every year, depending on the disease risk profile of your crop

- Other significant diseases this season included virus diseases and Botrytis grey mould (especially in narrowleaf lupin).

Introduction

In the last 20 years, grains production in southern NSW has changed significantly. Many landholders have moved entirely into grain production enterprises, removing livestock and pastures from their farming system. Agronomic practices have changed including stubble retention, minimum tillage and crop sequences. These changes have increased the disease burden across the farming system. Management of disease in the cropping system is now an important and annual consideration for many grain producers in southern NSW.

In 2020, sowing conditions were considered ideal across many districts, and crops were sown on time. Rainfall patterns and mild temperatures across the south provided ideal conditions for developing crops and resulted in some of the best crop yields seen for many years. These ideal conditions also allowed development of root and foliar diseases in broadleaf crops across the region. In many instances, even low levels of pathogens were able to develop into epidemic levels, despite the dry conditions in 2018 and 2019. In general, disease management practices across the region were very good, but there will be disease implications to consider moving into 2021.

Crop surveys have been undertaken for several years in southern NSW to monitor changes in disease prevalence, distribution and impact across farming systems and districts. Surveys are a valuable tool in the identification of emerging disease threats, monitoring IDM strategies, guide priorities for future research effort, and provide a mechanism for industry awareness and preparedness.

This paper discusses the priority diseases identified in 2020 crop surveys and implications for grains producers in 2021.

Methodology

With the assistance of local agribusiness, 45 pulse crops and 30 canola crops were sampled in 2020 at the early flowering to early pod filling stage (early August to late September). Crops details were collected including GPS location, previous cropping history and herbicide use. Crop locations were restricted to the southern half of NSW, that is south of Dubbo to the Victorian border.

Six pulse crop species were surveyed (albus lupin, narrowleaf (NL) lupin, faba bean, field pea, lentil and chickpea) and one oilseed crop (canola). There were no targets set for each species, but rather the number of crops sampled reflected the frequency of crops across the region.

At each crop a diagonal transect was followed starting at least 25m into the crop from the edge, to avoid any double sown areas, roadsides, dam or trees. At 10 locations at least 25 m apart along the transect, a row of 10 random plants was assessed for symptoms of foliar disease and any other abiotic issues present. At five locations (every second assessment point), five random whole plants along a row were collected for detailed assessment of disease and root health. The samples were prepared for assessment of fungal DNA concentrations at SARDI.

Table 1. The breakdown of commercial crops assessed and sampled as part of the 2020 IDM crop survey.

Region | NL lupin | Albus lupin | Chickpea | Field pea | Faba bean | Lentil | Canola | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Riverina | 6 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 32 |

SW Slopes | 8 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 16 | 36 |

CW Slopes and Plains | 2 |

|

|

|

|

| 6 | 8 |

Total | 16 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 31 | 76 |

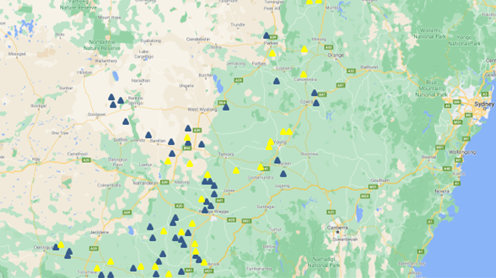

Figure 1. Distribution of pulse and canola paddocks assessed as part of the 2020 IDM crop survey. 45 pulse crops (blue triangles) and 30 canola crops (yellow triangles) were sampled for the presence of foliar and root disease.

What did the survey find?

Sclerotinia (all pulses)

Sclerotinia diseases (stem rot and white mould) were the most prevalent diseases found across all pulses in this season’s survey. A combination of exceptional crop growth and frequent rain periods during late winter and spring provided ideal conditions for this pathogen to develop across a wide region of southern NSW and range of broadleaf crops in the rotation.

Symptoms of the disease included basal infections, stem lesions and pod infections. Basal infections are the result of direct infection of plants by mycelium from germinating sclerotia. As sclerotia in the soil soften in winter from wet soil conditions, mycelium is produced that grows along or just under the soil surface. Once this mycelium encounters a plant stem, direct infection occurs that can kill the plant completely. Symptoms appear as a fluffy white collar that occurs around the stem base at soil level (often referred to as collar rot). Newly formed sclerotia will also be produced in this tissue. Stem and pod lesions are the result of infection via ascospores, in a similar way to the infection process in canola. Apothecia (flattened golf tee like fruiting structures of the Sclerotinia fungus) germinate from sclerotia in the soil. The apothecia produce and release airborne ascospores that land on and infect suitable plant tissues, often old senescent leaf and flower tissue or pods. Symptoms appear as fluffy white mycelium on the outside of stems and on pods (particularly lupin), often killing the plant above the lesion. Newly formed sclerotia often develop either within infected stems or on the outside, if conditions are favourable.

Table 2. Proportion of pulse crops inspected and found to have Sclerotinia spp. present as part of the 2020 IDM crop survey.

| NL Lupin | Albus lupin | Chickpea | Field pea | Faba bean | Lentil |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

No. of crops sampled | 16 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 4 |

No. of crops with Sclerotinia | 13 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 |

% of crops infected | 81% | 60% | 50% | 43% | 71% | 25% |

Implications for 2021

Sclerotia produced by infected crops in 2020 pose a significant disease threat in 2021 and beyond. Many of the crops detected with the disease in 2020 had been sown to successive cereal crops in 2018 and 2019, meaning the sclerotia responsible for the disease in 2020 were most likely formed prior to these cereal crops, therefore in 2017 or 2016. It is well known that sclerotia are long lived. The majority of sclerotia can survive for up to 5 years in the top five centimetres of soil, however this can increase up to 10 years if buried deeper and not exposed to microbial activity. Growers, agronomists and advisers should pay attention to crop choice and management for the next few seasons, especially those growers following ‘double break’ cropping systems. Sowing canola or pulses into paddocks known to have outbreaks of Sclerotinia in 2020 face a significant disease risk, especially in medium to high rainfall districts.

Blackleg (canola)

Blackleg, caused by the fungus Leptosphaeria maculans, was the most common disease observed in canola in the 2020 crop survey. Each of the 31 crops inspected had symptoms of the disease present at varying levels of severity. Symptoms ranged from leaf infection to stem cankered plants.

The high incidence of blackleg in commercial canola crops is not surprising in 2020 given the conducive conditions for the disease to develop this year. Differences in severity could be attributed to crop variety, fungicide use and proximity to old canola stubble. Frequent wet days throughout winter and spring provided multiple leaf wetness periods for infections to occur and proliferate. At the time of observation (mid-August to early September), those leaf infections that had developed towards the top of the crop canopy had potential to develop into upper canopy infection (UCI).

Implications for 2021

The large area sown to canola in central and southern NSW means there will be large areas of canola stubble in 2021 producing blackleg inoculum. Disease management in canola changes seasonally depending on the variety, seasonal conditions and frequency of canola in the rotation.

Consideration also must be given to disease risk factors impacting on the new season crop; is seedling protection important, do I need to apply fungicides for UCI, or are there diseases other than blackleg to consider? Often these risk factors cannot be addressed at the start of the season and require on-going crop monitoring and scouting for disease symptoms to make decisions that are cost effective. Scouting for symptoms is a powerful way to keep abreast of blackleg development within crops and make decisions around fungicide applications. Scouting is particularly important in the management of UCI.

More than ever, blackleg management in medium to high rainfall zones relies on fungicides as cultural practices become difficult to implement. With a suite of new fungicides and fungicide actives on the market, it is strongly recommended to rotate actives where possible to avoid the development of resistance in the pathogen population. CropLife Australia has on-line resources available for rotating fungicides in canola.

Another useful resource is the BlacklegCM app. Prior to sowing, use the BlacklegCM decision support tool to identify high risk paddocks and explore management strategies to reduce yield loss due to disease.

Botrytis grey mould (narrowleaf lupin)

Botrytis grey mould (BGM), caused by the fungus Botrytis cinerea, is a disease normally associated with lentil, chickpea, vetch and faba bean production. Crop surveys in 2020 also observed this disease in narrowleaf lupin crops, with 43% of crops infected. Outbreaks of BGM are initiated on senescent plant tissues, such as old leaves and flower parts before developing into larger, more damaging lesions. The large, dense crop canopies produced by narrowleaf lupin crops in 2020 favoured the development of senescent tissue following canopy closure and when light penetration into the canopy was hindered.

Symptoms of the disease included stem and leaf infections, and infections of old flower parts and pods. Whilst the disease can be confused with Sclerotinia white mould, the fluffy mycelium produced by the fungus is grey rather than white and no sclerotia are produced. Outbreaks of BGM are considered rare in narrowleaf lupin, but the causal fungus is ubiquitous. Extraordinary seasonal conditions in 2020 favoured development of this disease.

Implications for 2021

Old lupin stubbles affected by BGM present a significant inoculum source in 2021. The BGM fungus can infect other pulses including chickpea, lentil and faba bean. Spores of the BGM pathogen are airborne and will form readily on old infected stubble and be blown into surrounding crops. Care should be taken to avoid growing pulse crops (especially chickpea, lentil and faba bean) adjacent to old narrowleaf lupin stubbles in 2021. If this cannot be avoided, the crop should be managed as a medium to high disease risk and considerations made for foliar fungicide use where economically justified.

Virus (all pulses)

Virus diseases were evident in many pulse crops across central and southern NSW in 2020. All major pulse viruses require an aphid vector to infect host plants and the severity of virus diseases depends on the movement of aphids through a crop. Aphids require a living host plant to survive crop-free periods (‘green bridge’). For the 2020 season, good summer and autumn rainfall, and mild winter temperatures allowed for the build-up and maintenance of aphid activity across the region. This resulted in the appearance of virus symptoms in many pulse crops by late winter and early spring. Within the survey, virus symptoms were most noticeable in narrowleaf lupin and lentil crops.

Symptoms in narrowleaf lupin ranged from plants with shortened internodes and bunchy tops (typical for cucumber mosaic virus, CMV), to plants with a withered top, bright yellow leaves and premature death (typical for bean yellow mosaic virus, BYMV). Lentil crops featured shortened plants, bunchy growth and premature yellowing. Virus diseases in southern NSW during 2020 were not as severe as in northern NSW, where BYMV resulted in serious yield losses in a large number of faba bean crops. A number of narrow-leafed lupin crops in central NSW also suffered severe yield losses caused by CMV and Alfalfa mosaic virus (AMV).

Yield loss due to virus is not always easy to estimate compared to a fungal disease. Early virus infections tend to result in greater yield loss and subsequent plant death compared to infections later in the season when plants are more developed.

Implications for 2021

The occurrence of virus in pulse crops in 2020 demonstrated how dynamic virus diseases can be within the cropping system, and the influence of environmental conditions on the build-up and movement of virus vectors. The use of virus-free seed is of particular importance for narrow-leafed lupins, as CMV can be transmitted at high levels in narrow-leafed lupins. Sowing crops with virus infected seed can result in poor establishment and seedling vigour, in addition to becoming a source of virus infection throughout the crop. Following the agronomic recommendations of sowing into cereal stubble and sowing at the recommended sowing rate to avoid having thin or poorly established crops can also discourage aphid landings within crops and slow down virus spread.

Department of Primary Industries and Rural Development (DPIRD) in Western Australia offer commercial testing of pulse seed for virus, for more details on the diagnostic services provided contact DDLS Specimen Reception +61 (0)8 9368 3351 or DDLS@dpird.wa.gov.au.

Other diseases

Ascochyta blight

The most serious disease of chickpea in Australia was recorded in 30% of chickpea crops surveyed in 2020, however, reports of damaging levels of the disease in southern NSW were minimal. Strategic use of fungicides is highly effective at managing the disease which is spread through rain splash of spores. Be aware of the significant inoculum sources in 2021, as the pathogen survives on old infected chickpea stubble and seed.

Blackspot

The most common disease of field pea in Australia and most damaging in paddocks with a high frequency of field pea production. Spores of the fungus survive on old field pea stubble and in soil. Whilst blackspot was observed in 71% of field pea crops surveyed, only a single crop developed the disease at a damaging level. Avoid sowing next season’s crop adjacent to last year’s stubble and observe a four-year break between field pea crops in the same paddock.

Chocolate spot

Potentially the most damaging disease of faba bean and responsible for the nickname ‘failure beans’ in the 1990’s. The 2020 crop survey observed the disease in 43% of crops at low to moderate levels. Improvements in variety resistance and the range of foliar fungicide options available have significantly improved disease management and reduced potential for yield loss.

Bacterial blight

Mild winter conditions and few damaging frost events resulted in limited outbreaks of this disease compared to 2018 and 2019. Bacterial blight was observed in 28% of field pea crops inspected in the survey. The disease generally appears in low lying areas of field pea crops, which are most prone to frost and freezing injury. The disease is challenging and relies on pre-emptive disease management strategies such as maintaining at least a 3-year rotation between field pea crops and sowing disease-free seed. There are no post emergent disease management options. The bacterial pathogens survive on old field pea stubble and seed.

Phomopsis stem blight

Whilst this disease does not cause significant yield loss, presence of the disease within lupin crops poses a significant risk to livestock health. The causal fungus, Diaporthe toxica, produces a toxin as it grows within lupins that can kill grazing livestock, especially young sheep. Care should be taken when grazing lupin stubbles following harvest and especially following summer rain which stimulates growth of the fungus within stubble. It is rare to observe the disease whilst lupin plants are still green, but a single narrowleaf and a single albus lupin crop were observed with the disease during the survey. Typically, growth of the fungus becomes most apparent following harvest and after rain when fruiting structures of the fungus develop on lupin stubbles.

Conclusions

The results from the survey this year demonstrate the ability of pathogens to persist between years, even when conditions are unfavourable. Environmental conditions in 2020 allowed what were considered to be low levels of disease to build up quickly and becoming potentially damaging in broadleaf crops across the region. No new emerging disease threats were identified in 2020 from surveys, but several common diseases occurred at significant levels that will potentially impact for the next few seasons including Sclerotinia stem rot, blackleg and Botrytis grey mould.

Where possible an integrated approach should be used to manage disease in grains crops. More than ever we are becoming reliant on fungicides to maintain tight cropping rotations and high yields. The loss of fungicides from the system due to the development of resistance or detection of residues in end products will quickly remove these valuable tools from the system.

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support. Thanks to Joop van Leur for his contribution to the virus information in this paper.

The authors wish to thank all producers in NSW who were part of the 2020 Crop Survey.

Contact details

Dr Kurt Lindbeck

NSW DPI

Wagga Wagga Agricultural Institute,

Pine Gully Road, WAGGA WAGGA 2650

Ph: 02 6938 1608

Email: kurt.lindbeck@dpi.nsw.gov.au

GRDC Project Code: DAN00213,