Slugs – what can we learn from 2022

Author: Michael Nash (LaTrobe University) | Date: 27 Jul 2022

Take home messages

- Long term monitoring is vital to understand when slugs are posing the greatest threat, so management can be proactive to achieve the best results.

- Understand local context and the strengths and weaknesses of controls being applied.

- Attractive slug baits result in a greater likelihood that individuals will encounter a bait and consume a lethal dose.

- Metaldehyde products when stored over summer, as per label directions, results in no degradation or reduction in the level of the active ingredient metaldehyde.

Long term monitoring data provides an insight into next year’s slug risk

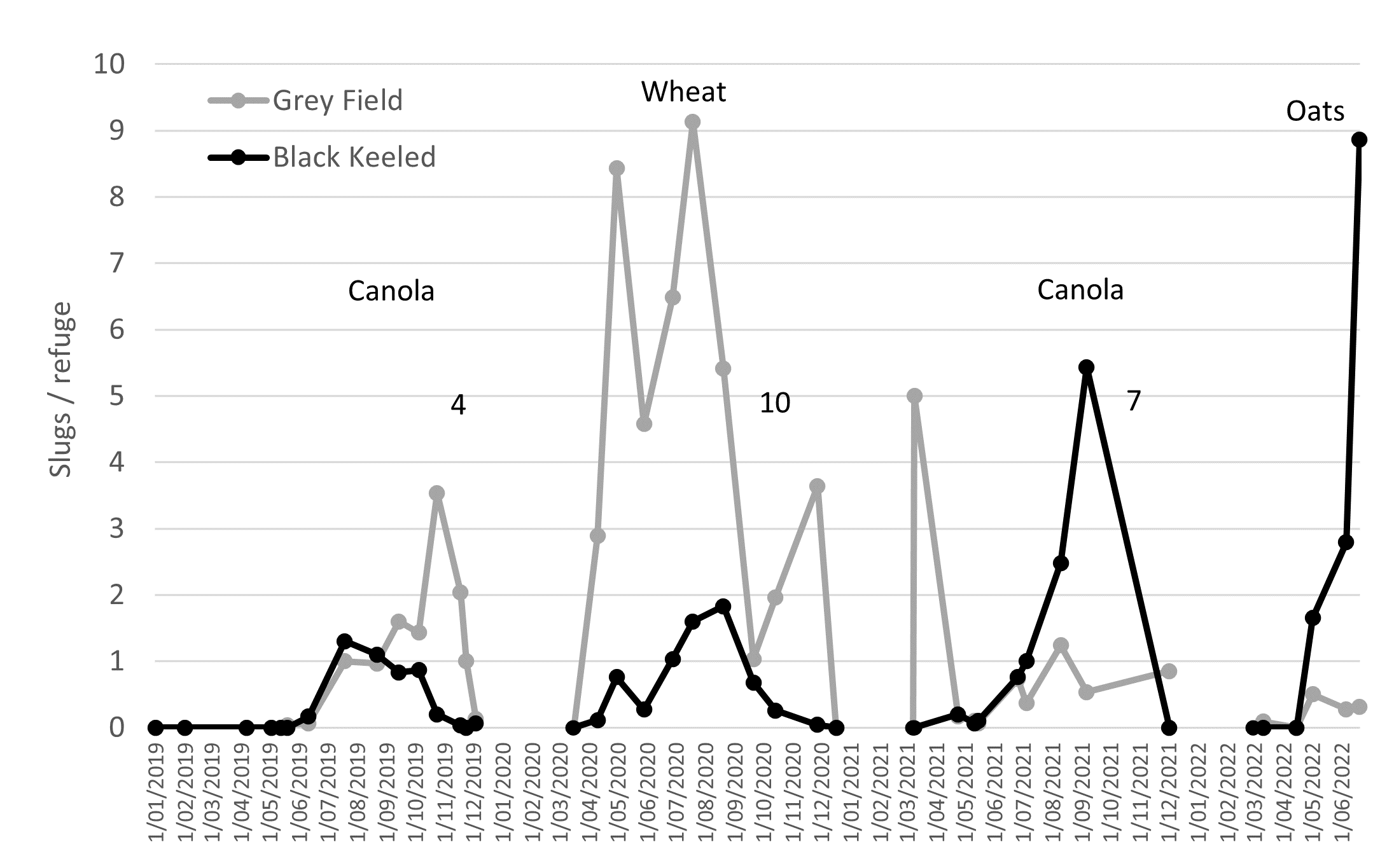

Slug activity and breeding has benefited from the environmental conditions associated with La Niña weather patterns over the last year, with large numbers observed in 2021-22. Taking longer to grow than grey field slugs, black keeled slug numbers were greater than 2021 in 2022 (e.g. Figure 1). In 2021, black keeled slugs were observed in April, but a large number also emerged mid-May when the “black wave of doom” is usually observed. This is consistent with overseas research: slugs emerge from the ground over an extended period. For example, grey field slug populations can continue to emerge from the soil for a period of up to 9 months (Port and Craig 2011).

What is observed on the soil surface is only the active proportion of the slug population, the total number is often much greater. This highlights the need to be vigilant — use long lasting baits for sustained control where monitoring of establishing crops every 3–4 days is not possible. In areas that had a long cool spring in 2021, numbers of grey field slugs built up as observed in spring monitoring (Figure 1). Proactive growers have been successful with slug control by applying bait after seeding to protect seed and seedlings, and reapplying bran-based pellets after substantial rainfall, that is, greater than 10–15mm.

Figure 1. Southwest Victoria slug population dynamics 2019–2022 as recorded under refuges from one site. Numbers indicate each season’s September–November decile.

What makes a good slug bait

Slug bait technology has come a long way since the traditional bran-based dry processed pellets. In Europe, the need to improve delivery of active ingredients to increase the number of slugs killed while reducing environmental impacts has seen the launch of new products with enhanced delivery systems for old active ingredients, resulting in greater return on investment due to a reduction in the kg/ha of product required. For example, new formulations of metaldehyde products kill a greater number of slugs, using less active ingredient and under a broader range of conditions. For slug baits to work, some basic principles are relied upon.

Individuals must first encounter a pellet, which requires:

- Individual activity — slugs must be actively searching for food.

- The number of baits distributed evenly — the focus on an increased pellet density alone has seen the manufacture of small pellets that increase the likelihood of individuals consuming a sub-lethal dose (see below). Pellets need to be evenly applied across the full width of application. Consistent pellet size, weight and density ensure no area is missed. Patchy control can occur when products with high variability are used and/or application equipment is not calibrated.

- Attractiveness of bait — snails and slugs display non-random movement towards attractive pellets (true definition of bait) compared to seedlings. In a laboratory trial run by South Australian Development and Research Institute using 100 Italian snails given a choice between a wheat seedling and an attractive bait, a significant (χ2 [chi square] = 129.62, df [degrees of freedom]= 2, p<0.001) percentage (87%) of individuals first touched the bait compared to a wheat seedling or made no choice.

Attractive products result in a greater likelihood that individuals will encounter a bait than a seedling. Once individuals have encountered a snail and slug bait, they must consume a lethal dose, which requires the following features:

- Palatability — addition of feeding enhancers ensures individuals consume enough active ingredient to ingest a lethal dose. In the case of metaldehyde that causes paralysis, consumption of a sub-lethal dose can be an issue with some products because individuals can’t continue to ingest enough to destroy their mucous cells.

- Enough bait for the target population — if product does not remain after a couple of days following application, it is usually due to large numbers of snails and slugs consuming it all. Re-application to those “hot spots” will be required.

- Enough toxicant in the bait — the loading of active ingredient determines the amount consumed; hence low loadings require more total product to be applied. In wet conditions, small pellets with greater surface area to volume ratios lose more active ingredient, hence less toxicant will be consumed. For products containing metaldehyde, it is generally recommended that 30–40g/kg is the optimum concentration.

Having a persistent bait, that slugs will consume to receive a lethal dose, allows for application before individuals are active. This timing often coincides with rainfall. Bran-based products, that breakdown after rain and have low initial loadings of active ingredient, need to be reapplied after heavy rainfall. Modern rainfast products continue to be effective for up to a month after application and rainfall. However, some products achieve rain fastness by including glue in the pellet matrix that can reduce palatability.

Combining what is known about the factors that make a good snail and slug bait has led to the delivery of products that have faster and more efficient mortality, with greater persistence. The continued improvement of delivery technologies has seen less of the active ingredients applied, hence lower environmental loadings, yet better crop protection and slug control, leading to better return on growers’ investment in slug bait.

Storing baits – the effect of temperature

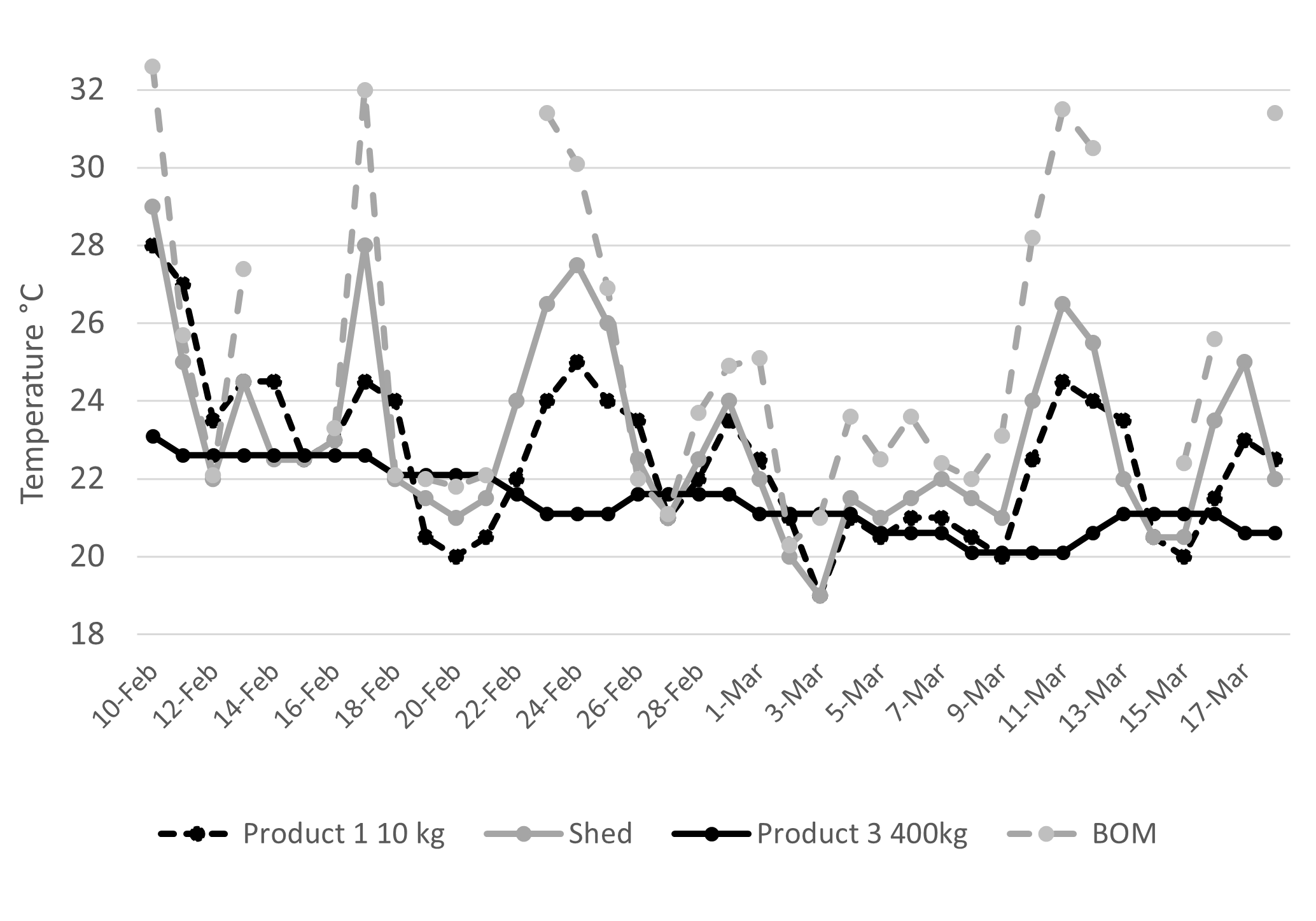

To test the effects of storage conditions on slug and snail pellets over an Australian summer, different commercially available products containing metaldehyde were placed in a shed at Warooka SA. Temperatures were recorded inside various pack sizes, inside the storage shed and from the Bureau of Meteorology data to quantify maximum temperatures.

Four different products with five different dates of manufacture were analysed for metaldehyde concentration after storage over the 2020 summer. Products were also stored inside a fridge (6.5°C) for the same period to act as controls (n = 10 treatments).

Maximum temperatures inside the 10kg package size were lower than Bureau of Meteorology data and ambient shed temperatures at Warooka (Figure 2). Bulka bag (400kg pack size) temperatures were lower again, suggesting mass provides an insulating effect that reduces the maximum temperature to which the stored product is subjected. As the maximum temperatures reached inside product packs was much lower than expected no degradation/reduction of metaldehyde was observed. Temperature data were recorded again in 2021 and the results supported the 2020 findings.

Results from chemical assays for metaldehyde concentration indicate no loss of active constituent during storage (Table 1). This experiment was repeated at a second site with the same outcome. That is, metaldehyde products stored for extended periods, as per product labels, will persist to kill slugs or snails.

Figure 2. Maximum storage temperatures at Warooka SA, 10 February 2020 until 17 March 2020. Data (hourly) was collected using iButton temperature loggers placed inside various product bags. Bureau of Meteorology data was from the nearest station ID: 022018.

Table 1: Metaldehyde concentrations determined by laboratory analysis.

Treatment number | Product | Pack size | Location | Metaldehyde concentration g/kg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Label | Tested after exposure | ||||

1 | Product 1 | 10kg | Warooka Retailer Shed | 50 | 49 |

2 | Product 2 | 25kg | 50 | 49 | |

3 | Product 3 2019 Batch | 400kg | 15 | 15 | |

4 | Product 3 2020 Batch | 400kg | 15 | 14 | |

5 | Product 4 2018 Batch | 20kg | 15 | 13 | |

6 | Product 1 | 1kg | Fridge | 50 | 50 |

7 | Product 2 | 1kg | 50 | 49 | |

8 | Product 3 2020 Batch | 1kg | 15 | 14 | |

9 | Product 3 2019 Batch | 1kg | 15 | 14 | |

10 | Product 4 2018 Batch | 1kg | 15 | 15 | |

Conclusion

Monitoring slug populations in the spring will provide insights into next season’s risk to establishing seedlings. Application of baits in the spring is not recommended, however slug and snail baits can be stored over the summer to ensure product is available when it needs to be applied.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank growers, retail agronomists and commercial clients that supported the research presented in thus paper. The author would also like to thank GRDC for support of the extension of this research.

References

Port G, Craig AD (2011) Vertical and horizontal movement by slugs. In ' IOBC/WPRS Bulletin.' (Eds S. Haukeland, W.O.C. Symondson, R.A. King, E.M. Shaw, J.R. Bell) pp. 179–182.

Contact details

Michael Nash

whatbugsyou@gmail.com

GRDC Project Code: MAN2204-001SAX,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK