Canola in northern farming systems

Author: Lindsay Bell (CSIRO), Jeremy Whish (CSIRO), Steven Simpfendorfer (NSW DPI), Jon Baird (NSW DPI), Kathi Hertel (NSW DPI), Andrew Erbacher (DAF Qld) | Date: 28 Feb 2023

Take home message

- Canola offers a range of rotational benefits for disease management, weed management, and the potential to widen sowing windows

- Understand when canola would most likely fit into your system to maximise its benefits and mitigate its risks – that is, when you should put it in your mix of crop choices

- Farming system data shows significant opportunities for canola, but risks are still significant

- Canola won’t suit all situations – several aspects need to line up to mitigate risk and maximise benefits. Critical aspects to consider include:

- Soil water at sowing – threshold >150mm in most locations to mitigate risk of low crop yields

- Sowing window – understand your optimal sowing window to manage the risk of frost and heat stress during critical periods

- Disease or weed issues – use canola where you are going to reap the benefits in subsequent years (e.g., winter grass problems, high Pratylenchus thornei nematode populations)

- Ensure sufficient N is available – avoid situations with low starting soil N, as this will be difficult to address in northern systems with applied fertilisers at sowing or in season.

- Preceding crops – be cautious of crops that host sclerotinia which increases disease risk (e.g., chickpea)

- Following crops – use canola leading into disease-sensitive crops/varieties, N availability is likely to be a little higher than after cereals, consider following with another break crop, i.e., a ‘double-break’ to ‘reset’ the system.

Introduction

Northern farming systems are challenged by a lack of reliable break crops that offer effective weed management options and help with reducing soil-borne diseases such as nematodes, Fusarium crown rot, and charcoal rot. Canola is one winter crop option that provides these benefits. Canola is a highly profitable staple crop in southern farming systems and a range of historical work has explored the wider potential of expanding its use further north (Holland et al. 2001, Robertson and Holland 2004). However, canola has traditionally been perceived as a risky crop in northern farming systems due to the greater frequency of high/low temperatures during grain filling, which often result in significant yield, quality and oil content losses.

Despite this history, there is now a wide range of varieties that fit a diverse range of niches in the farming system, ranging in phenology (or growing season length) to fit different sowing windows, and herbicide tolerance packages. Alongside improved planting equipment with better depth control, these advances address some of the limitations to using canola more widely in northern grain systems.

Sowing opportunities & timing – how often do they line up?

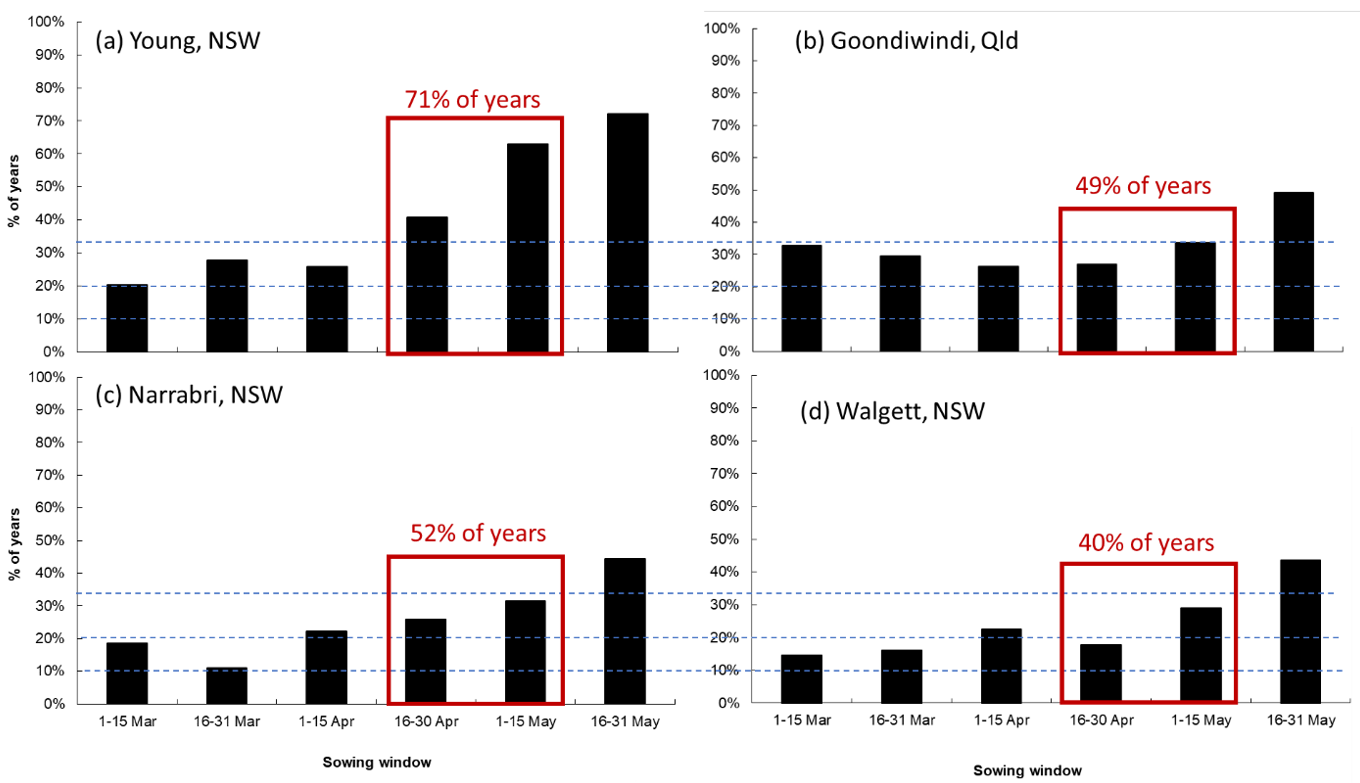

As canola has relatively small seed that must be planted shallow (<40mm depth), the duration of the sowing window to plant into surface moisture is limited. The reliability and frequency of suitable sowing events in the right window for canola can be a critical constraint to incorporating it more reliably into northern farming systems. Below (Figure 1) we compare the frequency that a sowing event is likely to occur in different fortnightly windows through autumn at a selection of locations. A sowing event is defined as a rainfall event exceeding potential evaporation over a 7-day period. This shows that in more temperate, winter dominant rainfall locations where canola is widely used (e.g., Young), a sowing opportunity occurs during mid-April to mid-May in over 70% of years. In contrast, in northern NSW and southern Qld with less and more variable autumn rainfall, the frequency of this sowing event is significantly lower at around 40-50% of years. Whilst this is likely to limit the frequency that canola could be effectively established in the north, it does show that in around half the years we are likely to still receive conditions that should allow canola to be sown in a viable window. This also shows that at many of our locations there are often sowing opportunities in early April (about 1-in-4 to 1-in-5 years), which may allow longer season canola cultivars to be used.

Figure 1. Historical (1956-2015) analysis of frequency of a sowing event (i.e. rainfall exceeding evaporation over a 7-day period) across fortnightly sowing windows comparing a southern NSW site (Young) with 3 northern locations. The red box depicts the optimal canola sowing window in late April and early May and the total frequency that such an event occurs in this period; blue dashed lines represent 1 in 10 years (10%), 1 in 5 years (20%) and 1 in 3 years (33%).

Matching variety and sowing time to mitigate heat/frost stress

Mitigating the risks of frost and heat stress at flowering is critical for maximising canola yield. In particular, the period 200–400-degree days after flowering (i.e., at peak flowering) is a key stress point when the crop is particularly susceptible to temperature or water stress (Whish et al. 2023). Table 1 shows the predicted optimal flowering windows for canola across various locations in southern Qld and northern NSW compared to a ‘typical’ canola growing region in southern NSW (Young – shown in bold). Firstly, the optimal window is typically shorter in northern environments due to a shorter period when frost and heat stresses are minimised. This results in narrow sowing windows for canola to flower in the narrow optimum window. Secondly, the optimal flowering window varies significantly across environments – from the earliest situations at Mungindi in the west, to later at Warwick in the east. This means it’s particularly important to look at this for your environment and select canola varieties with the appropriate phenology to match this optimal flowering window for a particular sowing date. These issues can be explored for your location and specific situation using the Canola Flowering Calculator.

Table 1. Predicted optimal window to start flowering and sowing date for an example variety with early/fast phenology across various environments spanning the northern grains region compared to a traditional canola region at Young, NSW. Predicted using the canola flowering calculator.

Location | Optimal window to start flowering | # Days in window | Optimal sow date for an early cultivar (e.g., Stingray) |

|---|---|---|---|

Young | 13 Aug – 15 Sept | 33 | 1 May – 17 May |

Narrabri | 18 July – 15 Aug | 28 | 1 May – 15 May |

Moree | 10 July – 8 Aug | 29 | 26 Apr – 10 May |

Goondiwindi | 6 July – 2 Aug | 27 | 20 Apr – 3 May |

Walgett | 12 July – 6 Aug | 25 | 26 Apr – 8 May |

Mungindi | 26 Jun – 23 July | 27 | 19 Apr – 26 April |

Warwick | 2 Aug – 25 Aug | 23 | 12 May – 20 May |

Condamine | 17 July – 12 Aug | 26 | 3 May – 15 May |

Soil water thresholds to mitigate risk

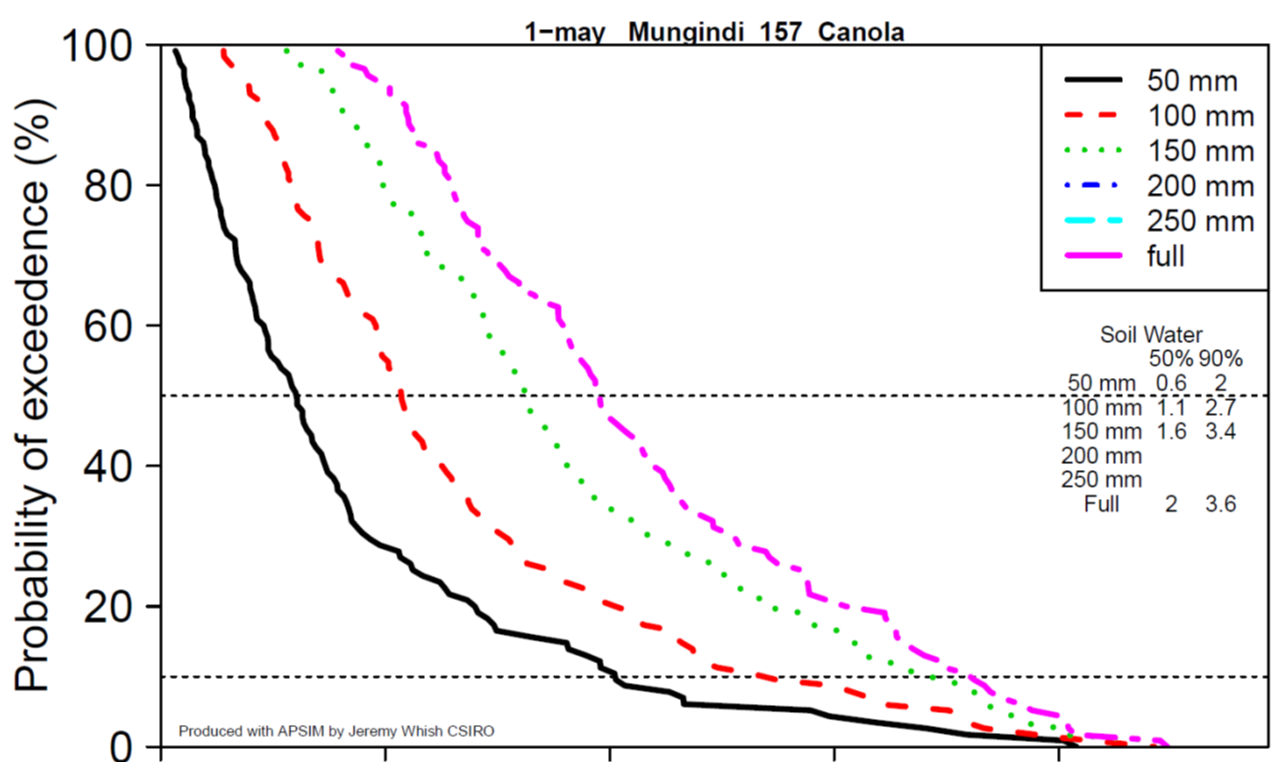

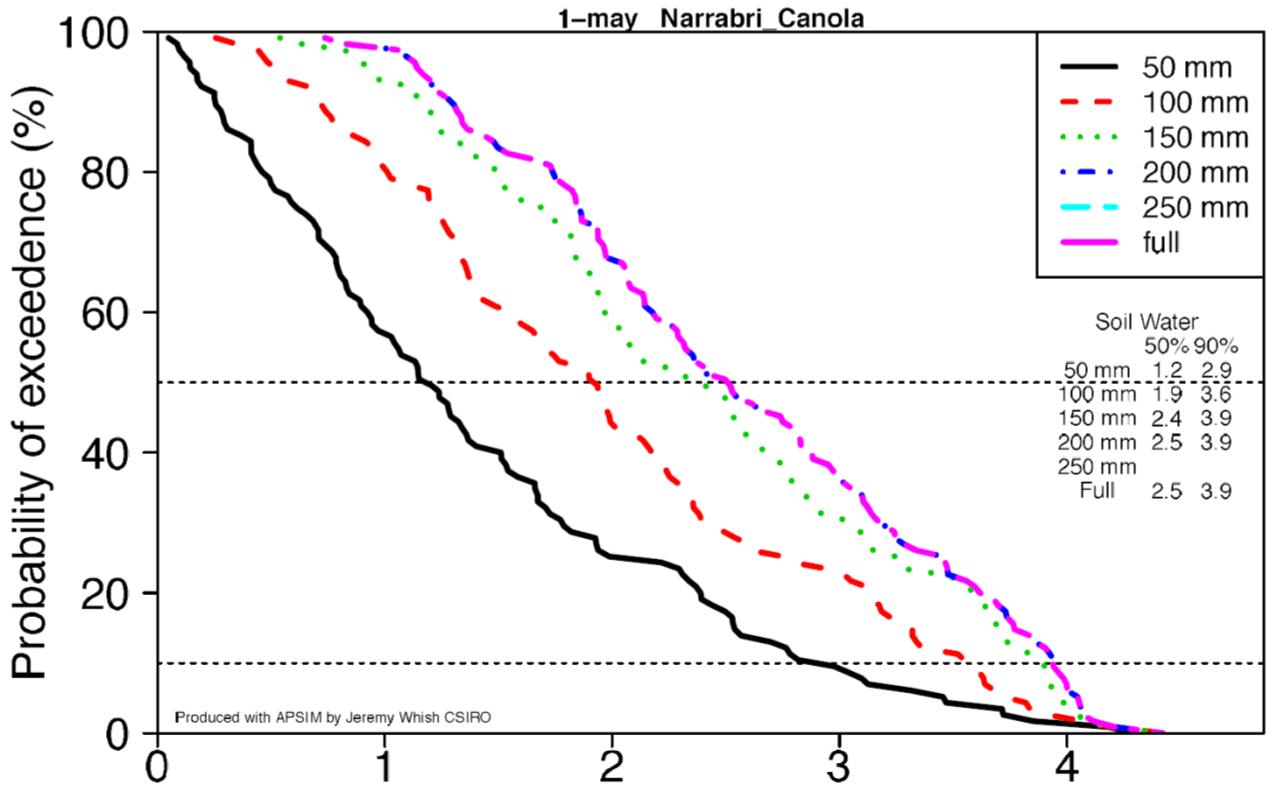

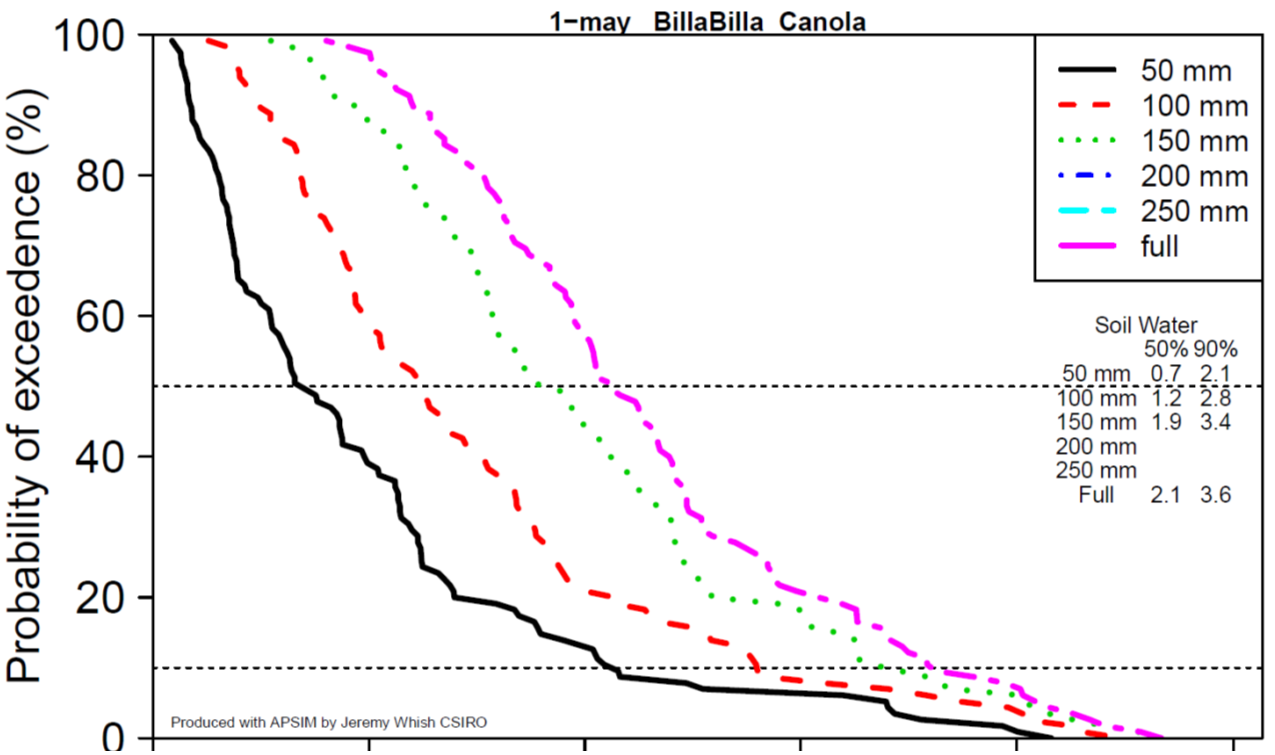

Seasonal rainfall variability and the availability of soil water at sowing are key drivers of yield expectations for canola in the northern region. In particular, soil water at sowing is far more important than in southern environments which receive more reliable winter rainfall. Figure 2 highlights the extent to which different starting soil water conditions impact yield potential for canola in some example northern locations. This shows that the median yield increases by about 0.5 t/ha for every 50 mm of extra PAW in the soil profile at sowing. To achieve a canola grain yield potential of >1.5t/ha (a benchmark break-even yield under typical price-input scenarios) in >60% of years, soil water at sowing would need to exceed 150 mm at Mungindi or Goondiwindi and exceed about 100 mm at Narrabri. When PAW at sowing is <100mm, the likelihood of achieving grain yields >2.0 t/ha is low (i.e., less than 1 in 5 years at most locations).

Figure 2. Simulated water-limited yield potential for canola across environments in northern NSW & southern Qld with different plant-available soil water conditions at sowing (indicated by different colours)

(Top = Billa Billa, middle = Mungindi, bottom = Narrabri).

Canola yields, water use efficiencies and legacies in farming systems experiments

As part of the northern farming systems research sites over the past 6 years, canola has been grown on 9 unique occasions across southern Qld, central NSW, and northern NSW under a diversity of seasonal conditions (Table 2). This provides a useful snapshot of what might be expected for canola performance in the northern region. From these sites, 3 of the 10 site-seasons achieved low yields (<0.5 t/ha), which were attributable to a frost event during early pod-fill (Narrabri 2017) and very dry conditions after sowing in 2019, when less than 200 mm of water (as rain or stored water) was available to the crop throughout the season. Five of the 9 site-seasons achieved grain yields of 2.5-3.5 t/ha, which occurred under conditions where the crop had access to over 350mm of water during the season. Most of these crops started with soil profiles >60% full prior to reaching the sowing window, which contributed around 30% of the water used by the crop. This was augmented by additional in-crop rain similar to the long-term average winter season rainfall across these locations (i.e., 200-300mm) except for Trangie in 2020 on a red soil with a low plant available water content (PAWC). These high yielding crops all started with >150 mm of PAW prior to sowing. The harvest index (0.23-0.27) and grain water use efficiency (WUE) (≤8.0) measured in these studies were less than those that are typically expected in more traditional canola-growing regions.

Table 2. Canola crop productivity (grain yield and biomass produced) & water used across farming systems experiments conducted 2015-2021.

Site-Year | Year | Yield | Biomass (t/ha) | Harvest Index | Water used (mm) | Pre-sow PAW | Biomass WUE | Grain WUE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

NARRABRI | 2017 | 0A | 8.0 | 0 | 320 | 146 | 25 | 0 |

NOWLEY | 2019 | 0.21 | 1.9 | 0.10 | 183 | 53 | 10 | 1.1 |

TRANGIE RED | 2019 | 0.44 | 1.8 | 0.25 | 139 | 22 | 13 | 3.2 |

BILLA BILLA | 2018 | 1.46 | 6.0 | 0.24 | 255 | 114 | 24 | 5.7 |

TRANGIE GRAY | 2020 | 2.70 | 13.6 | 0.20 | 403 | 148 | 34 | 6.7 |

TRANGIE RED | 2020 | 2.94 | 10.8 | 0.27 | 371 | 63 | 29 | 7.9 |

NARRABRI | 2016 | 3.06 | 10.5 | 0.29 | 642 | 225 | 16 | 4.8 |

PAMPAS | 2021 | 3.18B | 16.5 | 0.19 | 392 | 205 | 42 | 8.1 |

PAMPAS | 2015 | 3.55 | 15.2 | 0.23 | 517 | 152 | 29 | 6.9 |

A – Frost damage during early podding; B – Mouse damage removed 10-20% of pods.

At various farming system sites, canola has been grown under comparable conditions to other winter crops, providing insights into its relative performance in terms of grain yield and legacies such as extraction and replenishment of soil water and N availability in subsequent crops.

Firstly, despite the variability in canola productivity shown in Table 2, canola has produced grain yields between 34 and 70% (average of 55%) of those achieved in wheat under the same seasonal conditions. Canola yields have typically equalled those achieved in chickpeas under comparable seasons. Of course, the relative prices and input costs required for these crops will influence a direct comparison of profitability.

Canola left similar amounts of soil water at harvest compared to winter growing cereal crops or grain legumes in the same season. Some small differences (<20 mm) occurred in some seasons where canola left 15-30mm more water than the winter cereals, often due to earlier termination of canola while the cereal was still finishing. Despite there often being a slightly lower fallow efficiency achieved after canola than following a winter cereal, in the seasons with comparisons of PAW at the end of the subsequent fallow, there was little if any significant difference compared to either the cereals or legumes.

One clear and consistent observation was that the nitrogen that accumulated during the subsequent fallow after canola was often 20-35kg N/ha higher than following a cereal. Similar results have been consistently reported in southern regions. This occurs because canola leaf residue has a lower C:N ratio, and hence breaks down more quickly and releases more N than cereal residues.

Table 3. Differences between canola relative to a winter cereal (wheat, barley) or a winter legume (chickpea, fababean) grown in the same season in terms of grain yield, residual soil water (SW) at harvest, soil water and N mineralised over the following fallow.

Site-Year comparison | Canola yield (%) relative to: | Canola harvest SW (mm) relative to: | Canola SW at sow next crop (mm) relative to: | Canola fallow N mineralisation (kg/ha) relative to: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Wheat | Chickpea | Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | Cereal | Legume | |

Trangie-Red | 34 | +20 | +17 | +18 | ||||

Trangie-Red | 42 | -8 | -4 | +30 | ||||

Narrabri | 0 | +20 | +17 | +35 | ||||

Pampas | 68 | 95 | -4 | -9 | +4 | +2 | +28 | -10 |

Billa Billa | 60 | 108 | +14 | +3 | ||||

Trangie Gray | 57 | 300 | +28 | -20 | ||||

Pampas | 70 | 123 | ||||||

Narrabri | - | 108 | - | 0 | - | -18 | - | -10 |

Spring Ridge | - | - | 0 | -14 | +34 | |||

A – Frost damage during early podding

Crop rotation considerations

Clearly an important rationale for using canola in a crop sequence is to achieve some rotational benefits such as reducing populations of cereal or legume pathogens (e.g., root lesion nematodes, Fusarium crown rot), providing an alternative weed control option, and/or opportunities for using alternative herbicide chemistry.

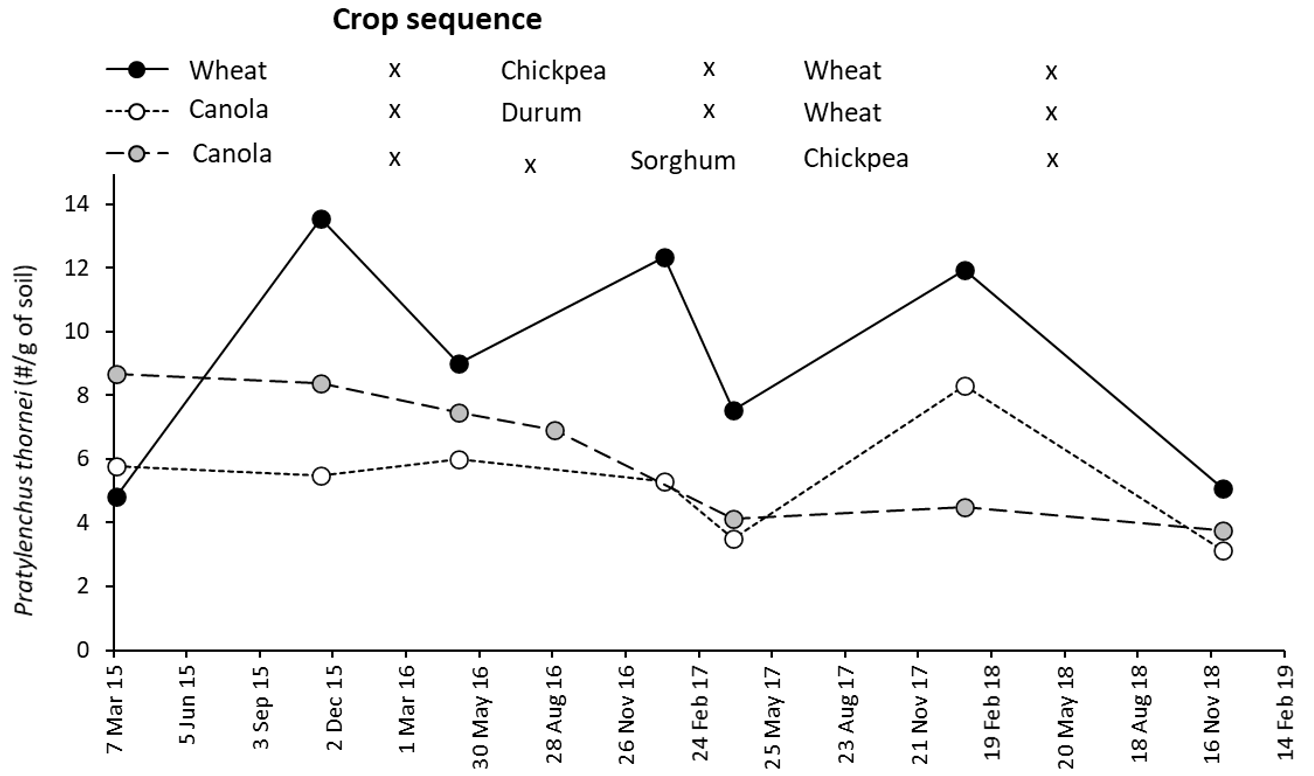

Consistent with previous understanding, our farming system data has shown that canola does not host the root lesion nematode, Pratylenchus thornei (Pt), the main problem species in the northern region. Hence, the population of this pathogen continues to slowly reduce under a canola crop whilst it will increase significantly under host crops like wheat or chickpea. The benefit for supressing Pt populations is further enhanced if the period of growing non-host crops can be extended for >24 months (Figure 3). Hence, growing canola in combination with non-host crops like durum wheat, cotton, or sorghum provides an effective mechanism for reducing the population of Pt to low levels in problem fields. However, it should be noted that canola is a host of a different root lesion nematode species Pratylenchus neglectus (Pn) which is more dominant on lower clay content soils in central and southern NSW. Hence, canola is not a good option for lowering Pn populations in these regions. Canola has also been shown to be a valuable alternative crop in northern cropping systems to reduce levels of Fusarium crown rot following winter cereal crops (Kirkegaard et al. 2004).

Figure 3. Root lesion nematode (P. thornei) populations in the soil over different crop sequences – shows the slow decline in numbers during non-host crops like canola coupled with durum or sorghum to provide a double break, compared to a rotation of host crops like wheat and chickpea.

While canola can offer several positive legacy benefits in a farming system, there are some potential risks to consider in subsequent crop management and selection. Firstly, canola doesn’t host beneficial arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), so there’s a risk that these populations will be reduced during a phase of canola, especially if it is preceded or followed by a long fallow, creating a long period without a host plant. Hence, on sites with low or marginal soil P, it is probably best to avoid following canola with a more AMF dependent summer crop (cotton, sunflower, mungbean and maize) or winter crop (linseed, chickpea and fababean). Secondly, several herbicides used in canola can have significant plant-back restrictions for some crop choices. This is important to consider in situations with double-crop opportunities into summer crops (e.g., mungbeans, sorghum). Finally, volunteer canola plants, particularly herbicide tolerant canola varieties, can be difficult to control in some subsequent crops and fallows. This can sometimes require more expensive herbicides be used to clean up canola volunteer plants in fallows or control these in the following crop.

Conclusions

Canola offers many potential benefits of crop diversification in a farming system; widening sowing windows, disease and weed management. Both experimental data and modelling suggest there are opportunities to use canola in northern farming systems when we have the confluence of sufficient accumulated soil water and a sowing opportunity in the right window. Whilst these conditions are unlikely to occur every year, they are not infrequent across many environments in the northern grain region.

While considering many of the agronomic considerations outlined above, it is important to also consider the sowing and harvesting equipment available to you. Accurate seed depth control will achieve better and more consistent establishment in canola, and hence sowing machinery that provides this is advantageous. Similarly, accessing a windrower for canola is often challenging and whilst direct heading is possible, it does impose greater risk of harvest losses and requires more attention to timing of harvest to mitigate risk.

References/further reading

Kirkegaard J, Lilley J, Meier E, Sprague S, McCaffery D, Graham R and Jenkins L (2019) 20 Tips for Profitable Canola: Northern NSW (2019)

Holland JF, Robertson MJ, Cawley S, Thomas G, Dale T, Bambach R and Cocks B (2001) Canola in the northern region: where are we up to? Australian Research Assembly for Brassicas, Geelong, 2-5 October, 2001.

Kirkegaard JA, Simpfendorfer S, Holland J, Bambach R, Moore KJ and Rebetzke GJ (2004) Effect of previous crops on crown rot and yield of durum and bread wheat in northern NSW. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 55: 321-334.

Serafin L, Holland J, Bambach R and McCaffery D (2005) Canola: Northern NSW Planting Guide. NSW Department of Primary Industries.

Robertson MJ and Holland JF (2004) Production risk of canola in the semi-arid subtropics of Australia. Crop and Pasture Science 55, 525-538.

Whish J, Lilley, J, Dillon S and Helliwell C (2023) Matching canola variety with environment and management - time of sowing, flowering windows and drivers of phenology. GRDC Update paper, Goondiwindi 2023.

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support.

Contact details

Lindsay Bell

CSIRO Agriculture and Food

203 Tor St, Toowoomba, Qld

Ph: 0409 881 988

Email: Lindsay.Bell@csiro.au

Date published: March 2023

GRDC Project Code: DAQ2007-002RTX, CSP1706-015RMX, CSP1406-007RTX, DAQ1406-003RTX,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK