Optimising control of annual ryegrass

Take home message

- Resistance to the Group 1 and Group 2 post-emergent herbicides in annual ryegrass is widespread and 23% of samples of annual ryegrass from NSW are resistant to glyphosate

- Resistance to pre-emergent herbicides remains at low frequencies, thus enabling their use as ‘backbone treatments’ in annual ryegrass control programs

- Control of annual ryegrass in higher rainfall zones needs to include double breaks (e.g., two broadleaf crops), double knocks in summer fallows, mixtures and sequences of pre-emergent herbicides and stacking of tactics within each crop

- Continuous cropping is selecting for increased dormancy and wider germination widows in annual ryegrass populations. Crop competition coupled with effective pre-emergent herbicide strategies can be used to reduce the impact of late emerging annual ryegrass.

Resistance to herbicides in annual ryegrass in NSW

In 2020/2021 a survey of resistant weeds was conducted across the grain growing regions of Australia. In this survey more than 1300 annual ryegrass samples were collected and tested for resistance to common post-emergent and pre-emergent herbicides. Resistance to the Group 1 herbicide Axial® (pinoxaden + cloquintocet-mexyl) was high across all states and 73% of samples collected in NSW were resistant to this herbicide (Table 1). Lower levels of resistance were present to the Group 1 herbicide clethodim with only 17% of samples collected in NSW resistant. Likewise, resistance to the Group 2 herbicides was also high with 86% of samples collected in NSW resistant to Hussar® (iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium + mefenpyr-diethyl) and 67% resistant to Intervix® (imazamox + imazapyr). Resistance to glyphosate (Group 9) is increasing in annual ryegrass and 23% of samples collected in NSW were resistant to this herbicide. No resistance to paraquat (Group 22) was detected in the survey.

Table 1. Extent of resistance in annual ryegrass to various post-emergent herbicides from random samples collected in 2020/2021 across Australia. Resistance is defined as 20% survival or greater.

State | Resistant samples (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Axial 100 | Clethodim | Hussar OD | Intervix | Glyphosate | Paraquat | |

National | 71 | 23 | 91 | 79 | 16 | 0 |

NSW | 73 | 17 | 86 | 67 | 23 | 0 |

Victoria | 73 | 10 | 95 | 86 | 22 | 0 |

Tasmania | 86 | 52 | 71 | 57 | 0 | 0 |

SA | 66 | 14 | 85 | 68 | 14 | 0 |

WA | 71 | 35 | 98 | 92 | 12 | 0 |

In contrast to the post-emergent herbicides, resistance to the pre-emergent herbicides (Table 2) was less frequent. There were low levels of resistance to trifluralin (Group 3) and Boxer Gold® (prosulfocarb + s-metolachlor; Group 15), but no resistance to Sakura® (pyroxasulfone; Group 15), Rustler® (propyzamide; Group 3), Luximax® (cinmethylin; Group 30) or Overwatch® (bixlozone; Group 13). This shows that pre-emergent herbicides are still likely to be effective for annual ryegrass control, where post-emergent herbicides are increasingly likely to fail. However, just because the survey failed to identify resistance to some herbicides does not mean resistance is not present.

Table 2. Extent of resistance in annual ryegrass to various pre-emergent herbicides from random samples collected in 2020/2021 across Australia. Resistance is defined as 20% survival or greater.

State | Resistant samples (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Trifluralin | Boxer Gold | Sakura | Rustler | Luximax | Overwatch | |

National | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

NSW | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Victoria | 21 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Tasmania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

SA | 38 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

WA | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Controlling annual ryegrass in higher yield grain production regions

Typically, high grain production regions have higher winter rainfall. In such regions, annual ryegrass can be difficult to control due to extended emergence of plants through the season. Surviving weeds can also set a lot of seed, leading to rapid increases in population size.

Trials in the high rainfall zone (HRZ) of South Australia and Victoria have identified a number of key strategies to managing annual ryegrass in high grain production regions:

Double breaks. Have two crops in a row where high levels of annual ryegrass control can be achieved. Some examples of double breaks include: faba beans followed by canola, canola followed by oaten hay, or oaten hay followed by faba beans. Well managed double breaks can effectively reduce annual ryegrass numbers to low levels.

Mixtures and sequences of pre-emergent herbicides. The extended emergence of annual ryegrass and the lack of effective in-crop herbicides means annual ryegrass can escape pre-emergent herbicide control, particularly when growing cereals. Using mixtures or sequences of pre-emergent herbicides that extend the period of control of annual ryegrass can help to reduce the number of annual ryegrass plants setting seed.

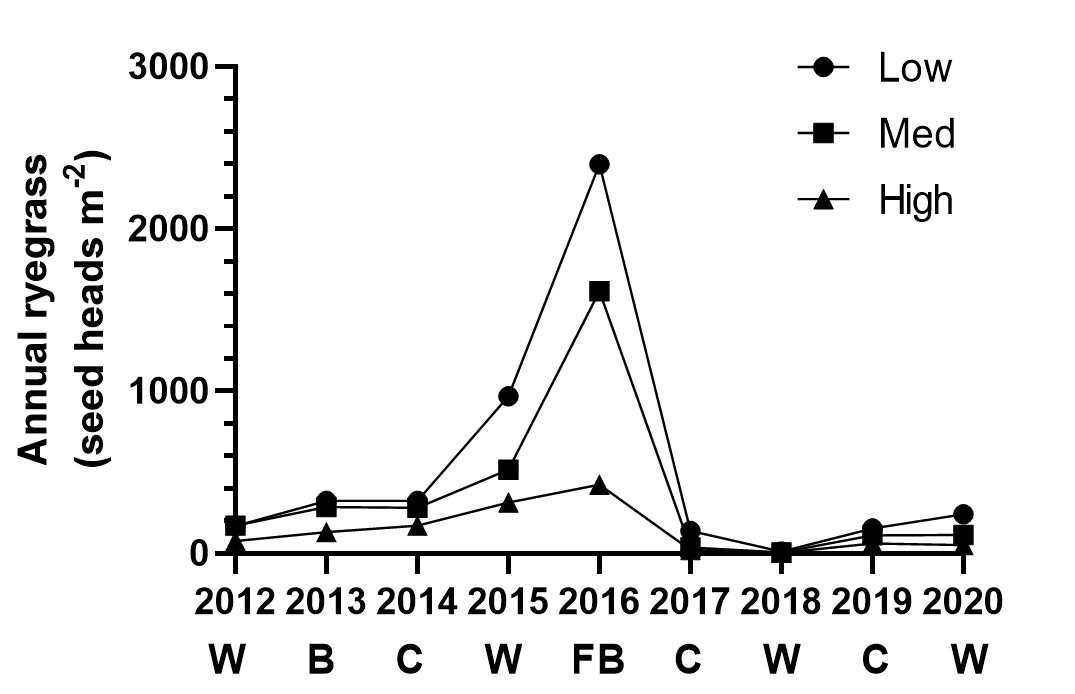

Stacking tactics. Stacking tactics within a season keeps annual ryegrass numbers lower. A long-term trial at Lake Bolac from 2012 to 2020 shows that the high cost strategy (2 to 4 annual ryegrass control tactics per crop) for annual ryegrass control was able to limit the increase in annual ryegrass numbers (Figure 1). As the high cost strategy was able to maintain annual ryegrass populations at a lower size and thereby reduce the impact on crop yield, it provided a cumulative $1613 ha-1 gross margin advantage, compared to the low cost strategy, over the 9 years of the trial. This trial also illustrates the value of the double break at reducing annual ryegrass numbers.

Figure 1. The mean effect of control strategy (low cost, medium cost, high cost) on annual ryegrass seed heads m-2 in a nine-year trial at Lake Bolac. “W” is wheat, “B” is barley, “C” is canola, “FB” is faba beans. There are significant differences in annual ryegrass seed head numbers between strategies in all years except 2017.

Harvest weed seed control (HWSC) is less effective in the HRZ due to the later harvest of crops. Later harvest means more annual ryegrass seed has shed prior to harvest. Despite this, HWSC is still a useful practice to reduce overall numbers of annual ryegrass. In higher yielding crops, it is more practical to make HWSC functional than perfect. For example, cutting low only through the patches of weeds can speed up harvest, while still reducing annual ryegrass seed numbers.

Changes in annual ryegrass emergence patterns

The adaptability of annual ryegrass is a major reason it is the most important weed of grain cropping Australia. In addition to evolution of resistance to herbicides, annual ryegrass can also evolve other traits that allow it to avoid control tactics. One of these is increased seed dormancy. There is evidence that populations of annual ryegrass have changed their emergence pattern to have more of the population emerge later in the season. This allows some of the population to avoid control by knockdown and pre-emergent herbicides.

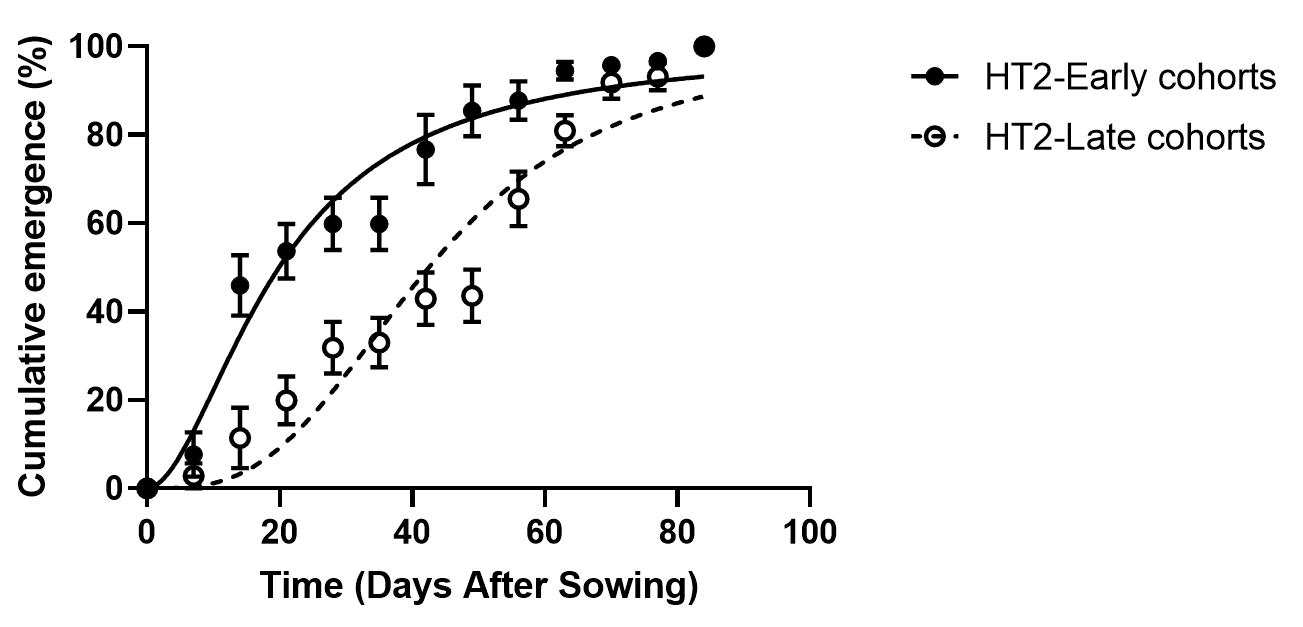

We have established that there is heritable variation for dormancy within annual ryegrass populations. In these studies, the early emerging and late emerging proportions of populations were separated and crossed among themselves. The progeny of these two sub-populations had different emergence patterns (Figure 2). There is about a 3-week difference in emergence between the two sub-populations.

Figure 2. Cumulative emergence of seeds of early and late cohorts selected from an annual ryegrass population.

Delayed emergence will make annual ryegrass more difficult to control, particularly as reliance on knockdown and pre-emergent herbicides for annual ryegrass control is high. Management strategies will need to adapt. Previously we have shown that the combination of crop competition with effective pre-emergent herbicides is one tactic that can limit the impact of late emerging annual ryegrass. Pre-emergent herbicide mixtures and sequences can also be employed to provide longer control of emerging annual ryegrass.

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support.

Contact details

Christopher Preston

University of Adelaide

PMB 1 Glen Osmond SA 5064

Ph: 0488 404 120

Email: christopher.preston@adelaide.edu.au

Date published: February 2023

® Registered trademark

GRDC Project Code: UA1803-008RTX, SFS1904-003WCX, UCS2008-001RTX,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK