Optimising annual ryegrass control

Optimising annual ryegrass control

Take home message

- Resistance to the Group 1 and Group 2 post-emergent herbicides in annual ryegrass is widespread and 23% of samples of annual ryegrass from NSW are resistant to glyphosate

- Resistance to pre-emergent herbicides is at low frequencies allowing their use to effectively control annual ryegrass

- Continuous cropping is selecting for increased dormancy in annual ryegrass populations. Crop competition coupled with effective pre-emergent herbicide strategies can be used to reduce the impact of late emerging annual ryegrass

- Choosing the right pre-emergent herbicide strategy for the situation will improve results.

Resistance to herbicides in annual ryegrass in NSW

A survey of resistant weeds was conducted across the grain growing regions of Australia in 2020/2021. From this survey 1,353 annual ryegrass samples collected were tested for resistance to the common post-emergent and pre-emergent herbicides. For the Group 1 herbicide Axial® (pinoxaden + cloquintocet-mexyl) resistance was common across all states with 73% of samples collected in NSW resistant (Table 1). However, resistance to the Group 1 herbicide clethodim was lower than Axial® with only 17% of samples collected in NSW resistant. Resistance to the Group 2 herbicides was common across Australia with 86% of samples collected in NSW resistant to Hussar® OD (iodosulfuron-methyl-sodium + mefenpyr-diethyl) and 67% resistant to Intervix® (imazamox + imazapyr). Perhaps the most alarming result was the increase in resistance to glyphosate (Group 9). This was identified in 16% of samples nationally, and 23% of samples collected in NSW. No resistance to paraquat (Group 22) was detected in the survey.

Table 1. Extent of resistance in annual ryegrass to various post-emergent herbicides from random samples collected in 2020/2021 across Australia. Resistance is defined as 20% survival or greater.

State | Resistant samples (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Axial®1 | Clethodim2 | Hussar® OD | Intervix® | Glyphosate3 | Paraquat4 | |

National (1,354) | 71 | 23 | 91 | 79 | 16 | 0 |

NSW (317) | 73 | 17 | 86 | 67 | 23 | 0 |

Victoria (183) | 73 | 10 | 95 | 86 | 22 | 0 |

Tasmania (21) | 86 | 52 | 71 | 57 | 0 | 0 |

SA (279) | 66 | 14 | 85 | 68 | 14 | 0 |

WA (554) | 71 | 35 | 98 | 92 | 12 | 0 |

1 Axial 100 EC (100 g/L pinoxaden + 25 g/L cloquintocet-mexyl) | ||||||

In contrast to the post-emergent herbicides, there was much less resistance to the pre-emergent herbicides identified (Table 2). There were low levels of resistance to trifluralin (Group 3) and Boxer Gold® (prosulfocarb + s-metolachlor, Group 15), with no resistance identified to Sakura® (pyroxasulfone, Group 15), Rustler® (propyzamide, Group 3), Luximax® (cinmethylin, Group 30) or Overwatch® (bixlozone, Group 13).

The pre-emergent herbicides are still likely to be effective for annual ryegrass control, where post-emergent herbicides are increasingly likely to fail. However, just because the survey failed to identify resistance to some herbicides does not mean resistance is not present.

Table 2. Extent of resistance in annual ryegrass to various pre-emergent herbicides from random samples collected in 2020/2021 across Australia. Resistance is defined as 20% survival or greater.

State | Resistant samples (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Trifluralin1 | Boxer Gold® | Sakura® 850 | Rustler® | Luximax® | Overwatch® | |

National (1,354) | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

NSW (317) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Victoria (183) | 21 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Tasmania (21) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

SA (279) | 38 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

WA (554) | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

1 trifluralin 480 g/L | ||||||

Changes in annual ryegrass emergence patterns

The adaptability of annual ryegrass is a major reason it is the most important weed of grain cropping in Australia. In addition to evolution of resistance to herbicides, annual ryegrass can also evolve other traits that allow it to avoid control tactics. One of these traits is increased seed dormancy. There is evidence that populations of annual ryegrass have changed their emergence pattern with more of the population emerging later in the season. This change allows more of the population to avoid control by knockdown and pre-emergent herbicides.

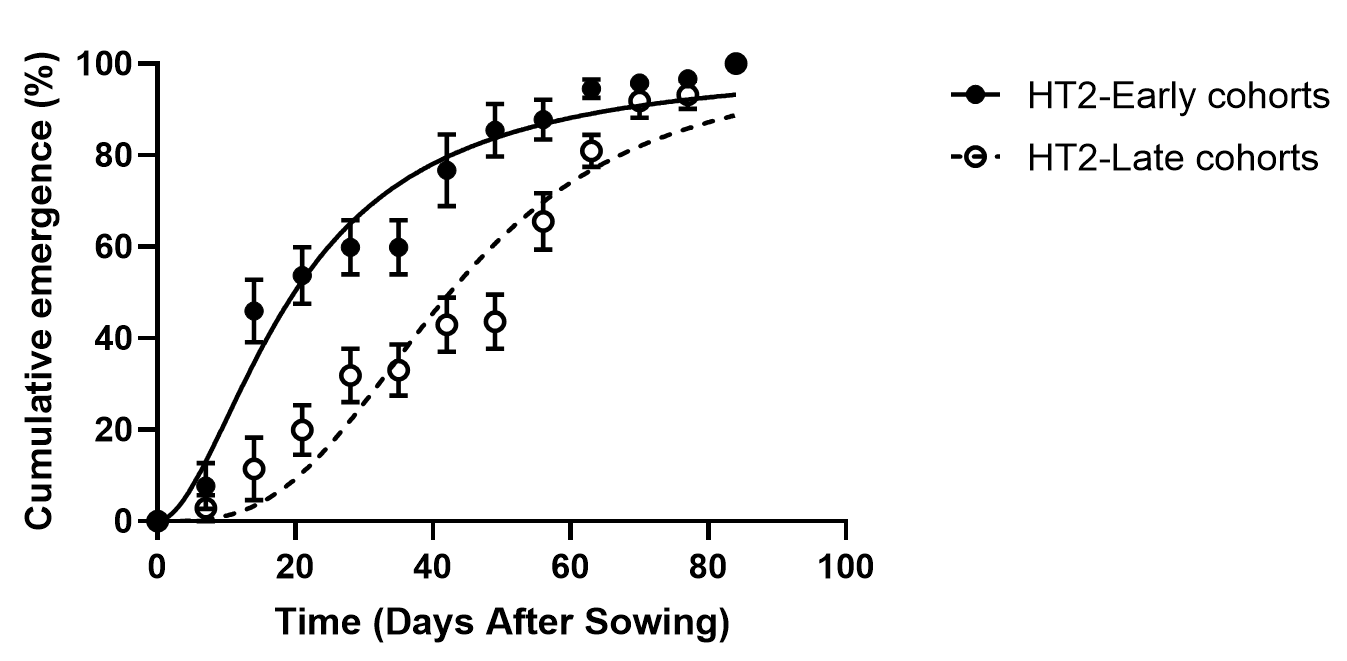

We have established that there is heritable variation for dormancy within annual ryegrass populations. In these studies, the early emerging and late emerging components of populations were separated and crossed among themselves. The progeny of these two sub-populations had different emergence patterns (Figure 1). There is about a 3-week difference in emergence between the two sub-populations.

Figure 1. Cumulative emergence of seeds of early and late cohorts selected from an annual ryegrass population.

This pattern of delayed emergence has previously been identified in brome grass and barley grass populations in southern Australia. It is likely that similar more dormant populations of other grass weeds, such as wild oats, could also be selected in continuous cropping fields.

Delayed emergence will make annual ryegrass more difficult to control, particularly as reliance on knockdown and pre-emergent herbicides for control of annual ryegrass is high. Management strategies need to adapt.

Previously we have shown that the combination of crop competition with effective pre-emergent herbicides is one tactic that can limit the impact of late emerging annual ryegrass. The use of pre-emergent herbicide mixtures and sequences to provide longer control of emerging annual ryegrass is another tactic that can be used. Stopping seed set of surviving annual ryegrass plants through crop-topping and harvest weed seed control is also valuable.

Pre-emergent herbicide strategies for annual ryegrass

Getting the best out of pre-emergent herbicides requires understanding of herbicide behaviour, soil types, rainfall patterns and crop tolerance. Table 3 provides the relative behaviour of recently registered pre-emergent herbicides and compares the newer products to existing products. The key factors are water solubility and binding to soil. The more soluble a herbicide is, the further it will move through the soil with each rainfall event. On the other hand, higher binding to soil components will reduce herbicide movement.

Table 3. Behaviour of some pre-emergent herbicides used for grass weed control.

Pre-emergent herbicide | Trade name | Solubility | KOC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Carbetamide | Ultro® | 3270 | Very high | 88.6 | Medium |

S-Metolachlor | Dual Gold®, Boxer Gold®* | 480 | High | 226 | Medium |

Metazachlor | Tenet® | 450 | High | 45 | Low |

Cinmethylin | Luximax® | 63 | Medium | 300 | Medium |

Bixlozone | Overwatch® | 42 | Medium | 400 | Medium |

Prosulfocarb | Arcade®, Boxer Gold®* | 13 | Low | 2000 | High |

Propyzamide | Edge® | 9 | Low | 840 | High |

Tri-allate | Avadex® Xtra | 4.1 | Low | 3000 | High |

Pyroxasulfone | Sakura®, Mateno® Complete* | 3.5 | Low | 223 | Medium |

Aclonifen | Mateno® Complete* | 1.4 | Low | 7126 | High |

Trifluralin | TriflurX® | 0.2 | Very low | 15,800 | Very high |

*Boxer Gold contains both prosulfocarb and S-metolachlor, Mateno Complete contains aclonifen, pyroxasulfone and diflufenican | |||||

In seasons with dry starts, there may not be sufficient rainfall to activate the less soluble herbicides, such as pyroxasulfone or propyzamide. Pairing these with tri-allate can help alleviate that problem. Heavy rainfall after sowing can result in crop damage from the more soluble herbicides such as metazachlor and cinmethylin. Using these herbicides on soil types with more organic matter and applying them after rainfall will reduce the risk of crop damage. In general, mixtures of pre-emergent herbicides will provide better and longer lasting annual ryegrass control.

Some pre-emergent herbicides can be used early post-emergent, which provides new opportunities for improved weed control. However, sufficient rainfall is required to activate the herbicides. This means that early post-emergent application should not be used alone to control annual ryegrass and should be used in conjunction with another pre-emergent herbicide applied prior to sowing.

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support.

Contact details

Christopher Preston

University of Adelaide

PMB 1 Glen Osmond SA 5064

Ph: 0488 404 120

Email: [email protected]

Date published

July 2023

® Registered trademark

GRDC Project Code: UCS2008-001RTX,