Key strategies for the management of Feathertop Rhodes grass

Key strategies for the management of Feathertop Rhodes grass

Author: Hanwen Wu (NSW Department of Primary Industries, Wagga Wagga Agricultural Institute) Md Asaduzzaman (School of Agriculture, Environemtal and Veternary Sciences, Charles Sturt University) | Date: 18 Jul 2024

Take home message

- Feathertop Rhodes grass (FTR) is a surface germinator (0–2cm), with little emergence at 5-cm soil depth. Strategic cultivation could assist FTR management.

- FTR emerges in wheat in southern NSW, however the emerged seedlings do not survive during the cropping season due to crop competition.

- FTR is highly sensitive to frost. Frosty winter conditions in southern NSW lead to plant death.

- FTR at the vegetative stage will be grazed by sheep and may potentially provide useful feed in certain situations. However, care should be taken not to let the weed set seeds.

- Integrating grazing with post-emergent herbicides is essential to control the regrowth of grazed plants, minimising seedset.

Introduction

Feathertop Rhodes grass (Chloris virgata Sw.) (FTR), a warm-season grass, has emerged as an important weed in grain cropping systems across Australia. It was once a major cropping weed in southern Queensland and northern New South Wales (Werth et al. 2013; Widderick et al. 2014) and has now become an emerging weed in the southern region of Australia. The invasive nature of this species is facilitated by its prolific seed production, with over 40,000 seeds per plant, and its high wind dispersal capability (Ngo et al. 2017).

FTR is very difficult to control, especially after the early tillering stage. Glyphosate alone is not effective to control this weed and no single weed management option will achieve complete control. Some group 1 herbicides are registered for FTR control but are typically restricted to one application each season due to the risks of developing herbicide resistance. The prolonged emergence from late winter/early spring to early autumn in southern NSW has added to the difficulties in control. An integrated approach is required for the effective management of this weed, including the combination of residual and post-emergence herbicides along with other non-chemical options. In southern NSW FTR plants that have emerged from early autumn onwards do not have time to progress to reproduction as a result of low temperatures and frosts in winter, which will eventually kill the plants (Asaduzzaman et al. 2022).

Young FTR plants could be an alternative source of feed for sheep. Feed value exceeds maintenance requirements at both the tillering and heading stages, but not at the maturity stage. It is possible to start with sheep grazing to utilise the young FTR plants and also to suppress the growth and seed production of FTR. However, grazed FTR plants have the potential to regrow and produce seeds, thereby replenishing the seed bank. Therefore, controlling the regrowth of FTR towards the end of the season is essential to prevent seed set and further infestations. Our research aimed to:

- understand emergence patterns of FTR in the field

- evaluate the frost impact on FTR

- evaluate grazing followed by herbicides on FTR.

Materials and methods

Seedling emergence at different burial depths

A seed burial study was conducted in a glasshouse at Wagga Wagga Agricultural Institute (WWAI) in February 2021. Two hundred seeds each of three FTR populations were sown at 0, 2, 5, and 10cm depths using two different soil types (sandy and heavy clay) to assess the impact of seed burial on emergence. Pots were mist-irrigated daily. Emergence was counted on a weekly basis for 7 weeks after sowing. A three-factor analysis determined the effects of soil type, burial depth, and population on emergence.

Seedling emergence and survival under wheat competition

An experiment was conducted in a field at WWAI to test crop competition on FTR emergence and survival. Wheat (cv BeckomA) was sown on 15 July 2020 at 75kg/ha with 22.5cm row spacing and 100kg/ha of di-ammonium phosphate. Two irrigation regimes (rainfed and irrigated) were compared with and without wheat. FTR seeds were sown at 600 seeds/m2 on 8 September 2020, with soil lightly cultivated for better seed contact. Irrigation in the irrigated treatments was applied post-planting and thrice weekly. Emergence was assessed using ‘count and remove’ and ‘count but not remove’ methods from 12 October 2020 (35 days after sowing (DAS)) until wheat harvest on 3 December 2020 (86 DAS). A split-split plot design with four replications was used: crop competition (± wheat) as main plot, irrigation regime (rainfed vs irrigated) as subplot, and assessment method (± count followed by removal) as sub-subplot.

Frost impact on FTR

Twenty intact plants each were collected from a field near Barellan on 25 August 2021 and 7 September 2022, and from Wagga Wagga on 1 September 2021, respectively. These plants were exposed to 11, 9 and 25 frosty days respectively before they were collected. All collected plants were cut 10cm above the base and re-potted in a glasshouse with an automated irrigation system. The controlled irrigation system was set to encourage the regrowth of frost affected plants. Any regrown plants were recorded.

The incidences of frosts were assessed in 2022 by taking field samples at different times at Wagga Wagga.Sampling began on 8 June 2022, with 20 intact plants collected fortnightly, and re-potted in the glasshouse as described above.

Integration of grazing and post-emergence herbicides

A field trial was conducted at WWAI to evaluate post-emergent herbicide treatments for controlling the regrowth of FTR. Five herbicide treatments were tested. Before treatment, FTR at the early seed head emerging stage was slashed on 23 February 2021, and mown plant material was removed. Irrigation (5mL) was applied on 1 March 2021 to alleviate moisture stress. Five first-knock herbicide treatments were applied on 2 March 2021, followed by a second knock of glufosinate (3.75 L/ha) or paraquat (2.4 L/ha) on 9 March 2021. The five 1st-knock treatments included haloxyfop (900 g/L) at 90 ml/ha, glyphosate (570 g/L) at 1.5 L/ha, a mixture of haloxyfop (900 g/L) at 90 ml/ha plus glyphosate (570 g/L) at 1.5 L/ha, propaquizafop (100g/L) at 500 ml/ha and clethodim (360g/L) at 330 ml/ha. Firepower® 900 (900 g/L haloxyfop) and Shogun® (100g/L propaquizafop) are registered for the control of FTR in fallow. A minor use permit (PER91513) of Arysta Select Xtra herbicide (360 g/L clethodim) followed by Gramoxone 360 Pro Herbicide is in place to cover FTR control in fallows in Queensland and NSW only. This permit expires 31 January 2025.

Herbicides were applied using a gas-powered hand boom fitted with AI nozzles (110 degrees) at 2 bars, with a water output of 100L/ha. The impact of herbicide treatments on FTR was visually assessed (0 = no control to 100 = complete control) at 56 days after the first knock at Wagga Wagga.

Results and discussion

Seedling emergence at different burial depths

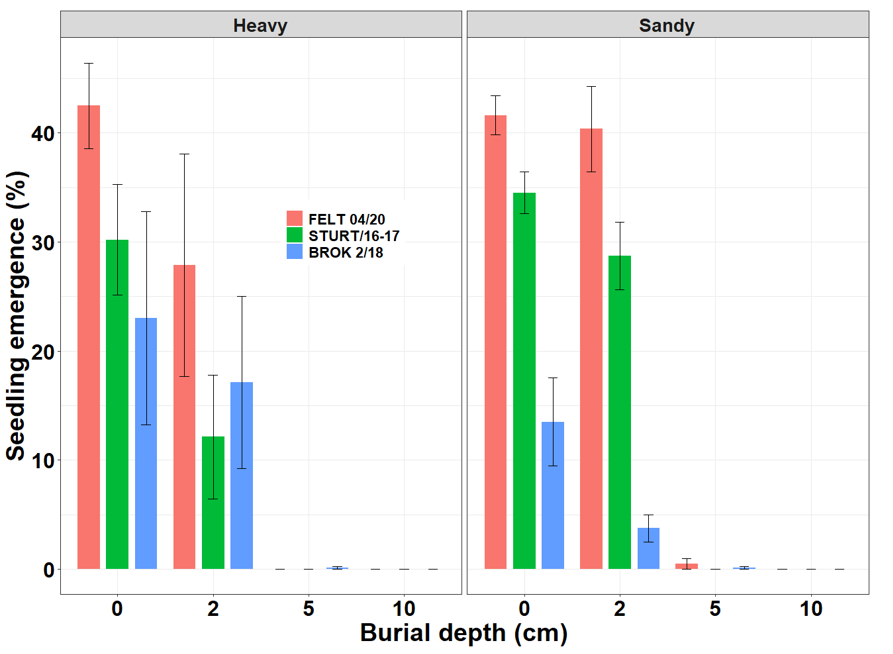

Seedling emergence mainly occurred from 0cm and 2cm depths in both sandy and heavy soils. No emergence occurred at burial depth of 10cm from both soil types (Figure 1). However, low level of seedling emergence also occurred at 5cm depth in both soils. These results suggest that FTR is a surface germinator (0–2cm depth) and seeds buried at shallower depths have a high probability of germination and emergence when soil moisture is not limiting.

Figure 1. Seedling emergence (percentage of 200 seeds buried) of three populations of FTR at four burial depths (cm) in sandy and heavy soils. Vertical bars indicate ± SEM (standard error of means).

Under ideal conditions, seed can emerge within 1–3 days, with more than 75% seedling emergence within 7 days after burial at the 0- and 2-cm burial depths. Strategic cultivation could be a useful control tactic in FTR management. The rapid emergence of FTR indicates that it is necessary to monitor the field for any suspected infestation after any substantial rainfall events during the spring and summer period.

Seedling emergence and survival under wheat competition

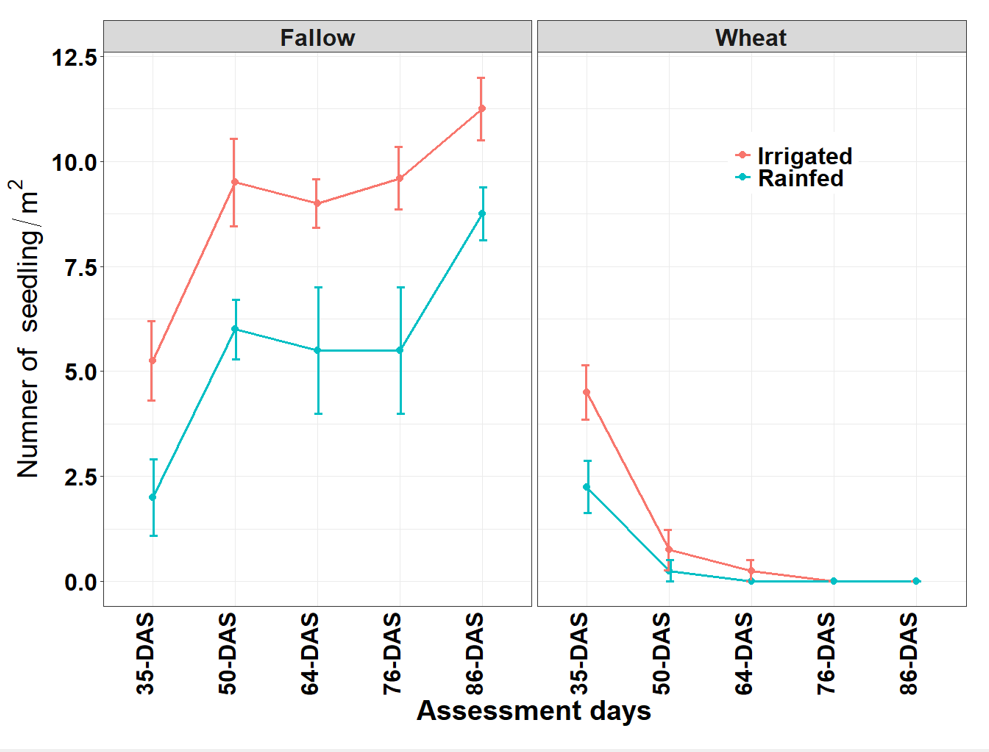

FTR seedling emergence and survival were initially similar with and without wheat (fallow) competition, but the emergence continued only in the fallow treatment (Figure 2). Seedling survival in the fallow improved with irrigation, whereas no plants survived 64 DAS in the wheat crop, despite additional irrigation.

Figure 2. Seedling emergence and survival of FTR (counted but not removed) with or without wheat under irrigated and rainfed conditions. Vertical bars indicate ± SEM.

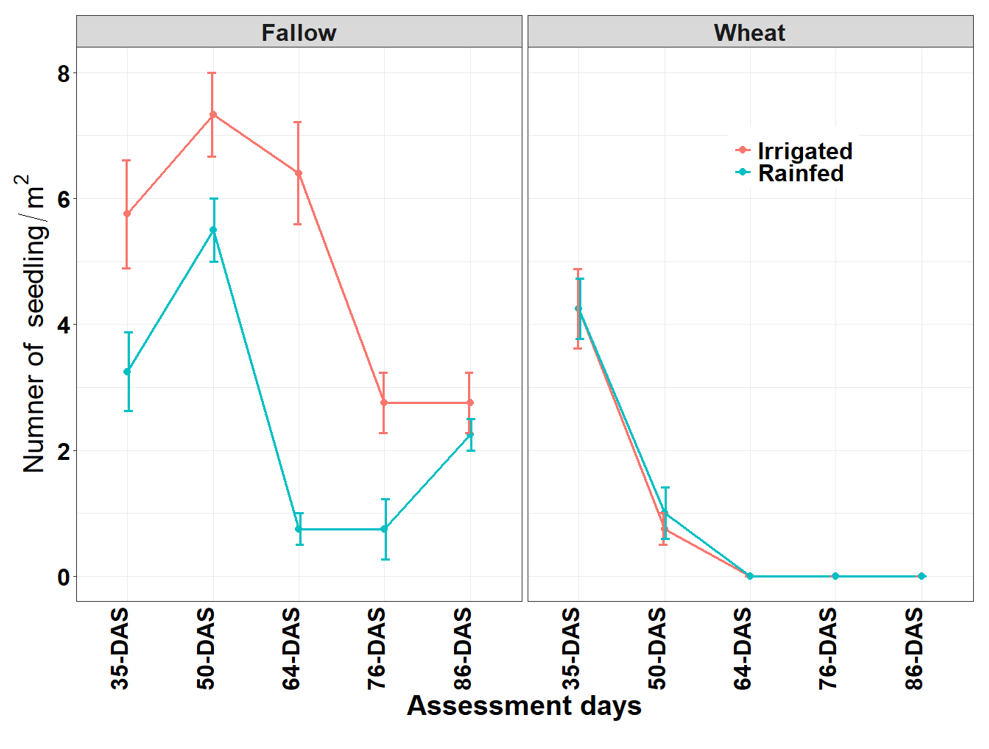

The patterns of seedling emergence were different in wheat and in winter fallow, with no further emergence beyond 64 DAS under wheat competition (Figure 3). However, without crop competition (fallow), there were multiple peaks of emergence, with two primary emergences in October (35 and 50 DAS) followed by two minor emergences in November (76 DAS) and December (86 DAS). Irrigation increased emergence when compared with the rainfed treatment at all observation times up until the final observation.

The FTR emergence pattern in wheat indicates that FTR is less likely to be a problem in winter crops. Even though FTR does emerge in spring in wheat crops in southern NSW, the strong crop competition due to canopy closure makes it impossible for the emerged seedlings to survive during the crop growing season. Control efforts should be focused on post-harvest because of the removal of crop competition.

Figure 3. Seedling emergence patterns of FTR (count followed by removal) over time with or without wheat under irrigated and rainfed condition. Vertical bars indicate ± SEM.

Frost impact on FTR

Over-wintered mature plants collected in the field in late autumn and early spring from Barellan (2021 and 2022) and Wagga Wagga (2021) failed to regrow in the glasshouse.

Table 1: Impact of frost duration on FTR regrowth in 2022, Wagga Wagga. Plants were collected in the field at fortnightly intervals and re-potted in the glasshouse to determine the regrowth. Since there were no further frost events after the end of September 2022 in southern NSW, the final assessment of the three different trials was conducted on 20 October 2022.

Sampling time | Total frosty days exposed | Percent plants survived (regrown) |

|---|---|---|

8 June | 1 | 20 (small plants with abnormal seed heads) |

22 June | 1 | 0 |

03 July | 8 | 0 |

20 July | 11 | 0 |

3 August | 11 | 0 |

18 August | 12 | 0 |

Mature plants exposed to varying numbers of natural frosts were collected in Wagga Wagga and re-potted in the glasshouse. Only the plants collected on 8 June 2022 had 20% regrowth and produced abnormal seed heads (Table 1). These plants only had experienced one frost before being collected. Plants collected after 8 June did not regrow.

These results suggest that FTR is highly sensitive to frost. Natural frosty winter conditions in southern Australia will cause the death of FTR plants, potentially slowing down FTR spread in southern Australia. Preventing seed set before frosts is therefore crucial for managing FTR proliferation.

Integration of grazing and post-emergence herbicides

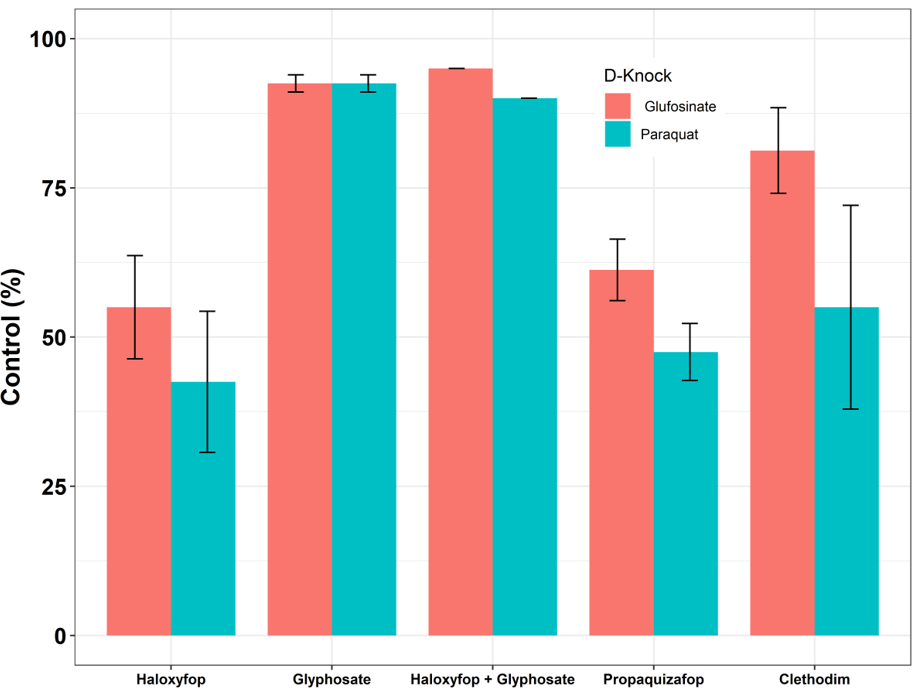

Herbicide treatments had significant (p<0.001) effects on the regrowth of mowed FTR plants. The two double-knock treatments, with either glyphosate or glyphosate + haloxyfop as the first knock followed 7 days later by paraquat or glufosinate as the second knock, achieved more than 90% control of the newly regrown FTR (Figure 4). However, the remaining three double-knock treatments of haloxyfop, propaquizafop or clethodim as the first knock followed by paraquat or glufosinate as the second knock did not achieve satisfactory control (42–81%).

Figure 4. Efficacy of five different herbicide treatments (as first knock) followed 7 days later by glufosinate or paraquat as the second knock on the regrown FTR plants. Vertical bars indicate ± SEM.

References

Asaduzzaman M, Wu H, Koetz E, Hopwood M, Shepherd A (2022) Phenology and population differentiation in reproductive plasticity in feathertop Rhodes grass (Chloris virgata Sw.). Agronomy 12, 736.

Ngo TD, Boutsalis P, Preston C, Gill G (2017) Growth, development and seed biology of Feather Fingergrass (Chloris virgata) in southern Australia. Weed Science 65, 413–425.

Werth J, Boucher L, Thornby D, Walker S, Charles G (2013) Changes in weed species since the introduction of glyphosate-resistant cotton. Crop and Pasture Science 64, 791–798.

Widderick M, Cook T, McLean A, Churchett J, Keenan M, Miller B, Davidson B (2014) Improved management of key northern region weeds: diverse problems, diverse solutions. 19th Australasian Weeds Conference, Hobart, September 2014, pp. 312–315.

Contact Details

Hanwen Wu

NSW DPI, Wagga Wagga Agricultural Institute

Pine Gully Road, Wagga Wagga NSW 2650

0401 686 218

hanwen.wu@dpi.nsw.gov.au

GRDC Project Code: DAN1912-034RTX,