Soil health stocktake Queensland

Soil health stocktake Queensland

Take home message

- Total Organic Carbon: average across all locations in central and southern Queensland was 1.21% (0–10 cm) and 0.89% (10–30 cm)

- Phosphorus: 57% of paddocks (270) recorded low levels of phosphorus (< 7 mg Colwell P/kg and < 50 mg BSES P/kg) in 10-30cm soil layer that indicate a potential response to the application of deep phosphorus

- Potassium: 35% of paddocks (270) recorded low levels of exchangeable potassium in 10-30cm soil layer that indicate a potential response to the application of deep potassium.

Background

Soil health can be defined as, ‘the continued capacity of soil to function as a vital living ecosystem that sustains plants, animals and humans’ (Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2024). Soil health is complex as it is driven by physical, chemical and biological properties, processes and their interactions with farming practices. Hence, soil health and how it is impacted by management is best considered in a holistic manner.

Reduced soil organic matter and soil fertility where native vegetation has been removed are key indicators of soil health decline in Australia. This decline is most significant on soils that are under long-term cultivation (Dalal & Mayer 1986) and is becoming a major constraint to the productivity and sustainability of Australian farms.

Soil sampling is one way of investigating soil properties. This is often conducted by an agronomist who provides a recommendation to the grower outlining the required fertiliser application for the subsequent crop. Without an understanding of the soil analysis and/or its connection to soil health, growers cannot make informed management decisions. The ‘Healthier soils through better soil testing’ project was funded in February 2022 by the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries Queensland and the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program to improve management of soil health.

What was done

The project was delivered across 2022–2024 with three main activities: soil testing, action learning workshops, and participatory action (on-farm) research. This report will focus on the soil testing results. The key functions of soil health and the indicators assessed were:

- The soil’s ability to maintain soil organic matter (measured by soil organic carbon)

- The soil’s ability to supply nutrients for plant growth (measured by available nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium)

- Good soil structure (measured by dispersion and exchangeable sodium percentage)

- Free from toxicities (measured by salinity and chlorides)

- Free from pathogens (measured by Predicta®B)

- Levels of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) (measured by Predicta®B).

Ninety cropping properties were identified by the project team across southern and central Queensland. The project team soil sampled three paddocks on each of these properties (a total of 270 paddocks) (Figure 1). The three paddocks were identified via a one-on-one semi-structured interview with the grower (and their agronomists where appropriate). These interviews assisted the project team to target soil sampling to investigate the grower specific questions and so maximise their learning. Paddocks were chosen to compare the impact of different scenarios on soil properties such as differences in management practices, soil type, or length of cultivation. The project team then conducted soil sampling with rigorous protocols to ensure scientific integrity of the data. Where possible this process was done with the grower in their own paddocks, so the grower could see and feel their own soil beyond the surface.

Figure 1. Map of participating properties indicated by markers.

The soil sampling procedure took six cores from each paddock. Each core was segmented into 0–10, 10–30, 30–60, 60–90, 90–120 (if possible) cm layers, with each layer from the six cores bulked. The 0–10 cm and 10–30 cm layers were analysed for pH (H2O), pH (CaCl2), Total Organic Carbon, electrical conductivity, chloride, nitrate nitrogen (N), ammonium N, dispersion, exchangeable cations (aluminium, calcium, magnesium, potassium, sodium), total N, Colwell phosphorus, phosphorus buffering index (PBI) and BSES phosphorus. The 30-60, 60-90, 90-120 cm layers were analysed for pH (H2O), pH (CaCl2), electrical conductivity, chloride, nitrate nitrogen (N), ammonium N, dispersion and exchangeable cations (aluminium, calcium, magnesium, potassium, sodium). A further sample (0–15 cm depth) was taken from each paddock and analysed using Predicta®B DNA-based soil testing service.

Results

The data collected provided a comprehensive benchmark of soil physical, chemical and biological properties of Queensland cropping paddocks. Several key insights were drawn from the cumulative data.

1. Plant available N (kg/ha) (measured as nitrate nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen and calculated using a bulk density of 1.3) indicated that 204 of the 270 paddocks (76%) had below 100 kg N/ha in the 0–90 cm part of the soil profile that grain crops typically access. 143 paddocks (53%) had very low levels of 50 kg N/ha or less. This is important because ~45 kg N/ha is required to grow 1 t wheat/ha at 13% protein, while many of the growers were targeting 2–3 t/ha (data not shown).

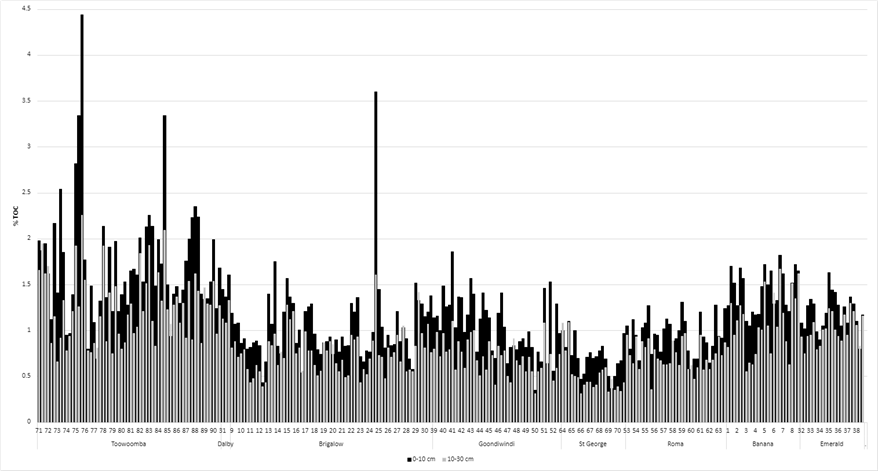

2. TOC levels (method 6B1 – Heanes wet oxidation) varied across geographical locations. The western locations recorded lower TOC. The lowest 0.37% TOC in 0–10 cm was recorded at St George (long term cropping paddock, low Colwell phosphorus, low annual rainfall). The highest level of 4.44% in the 0–10 cm layer was recorded at Toowoomba (long term forage pasture paddock with very high Colwell phosphorus and higher long-term rainfall). The average across all locations was 1.21% (0-10cm) and 0.89% (10–30 cm) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Total Organic Carbon (%): 0–10 cm and 10–30 cm for each paddock (listed 1 – 270) by location.

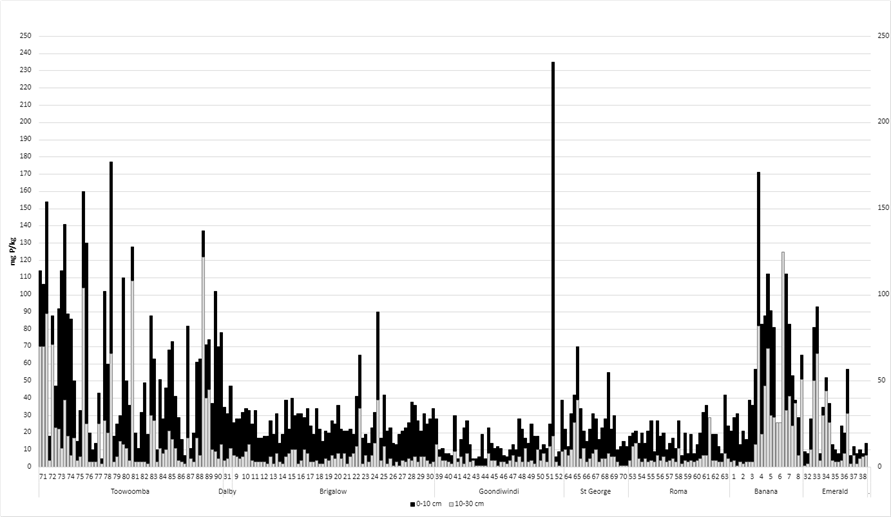

3. Colwell P levels (considered to indicate plant available phosphorus) were lowest in the Goondiwindi, Roma and St George regions and highest in the Toowoomba and Banana regions (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Colwell phosphorus (mg/kg): 0–10 cm and 10-30 cm for each paddock (listed 1–270) by location.

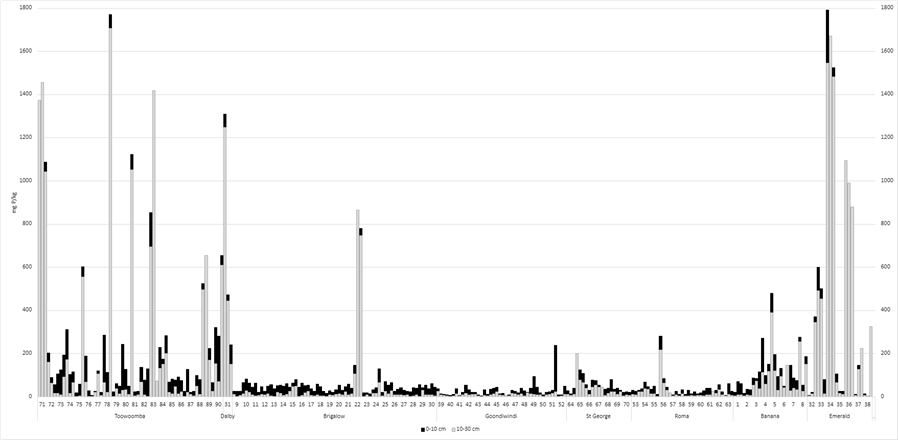

4. SES phosphorus (considered to indicate P reserves that slowly become available) was considered low (< 50 mg P/kg in 10–30 cm layer) in 206 paddocks with the lowest levels detected in the Brigalow, Goondiwindi, St George and Roma regions (Figure 4). The lowest result was 5 mg P/kg in the 0–10 cm layer and <1 mg P/kg in the 10–30 cm layer. These are extremely low levels and will severely limit plant growth. Some paddocks had very high levels of BSES P due to their minerology.

Figure 4. BSES phosphorus (mg/kg): 0–10 cm and 10-30 cm for each paddock (listed 1–270) by location

Responses to the application of deep P are likely if levels in the 10–30 cm layer are < 7 mg Colwell P/kg and < 50 mg BSES P/kg (Bell 2023). Of the 270 paddocks tested, 155 paddocks (57%) fell into this category.

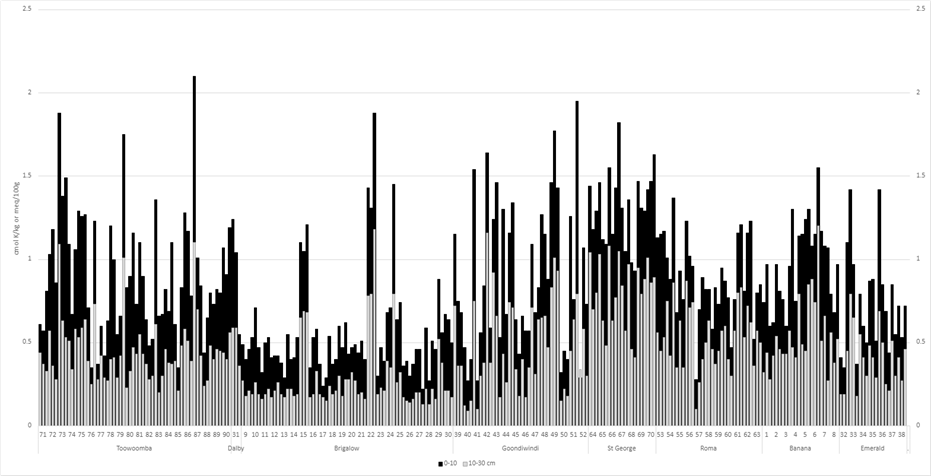

5. Exchangeable K was observed to be consistently low in the Brigalow region and in some soils in the Goondiwindi region (Figure 5). Responses to the application of deep K are likely if levels in the 10–30 cm layer are: < 0.2 cmol K/kg for <10 cmol/kg cation exchange capacity (CEC); < 0.25 cmol K/kg for CEC 10–30 cmol/kg; and < 0.35 cmol K/kg for CEC >30 cmol/kg (Bell 2023). Of the 270 paddocks tested, 95 paddocks (35%) fell into this category.

Figure 5. Exchangeable potassium (cmol K/kg): 0–10 cm and 10-30 cm for each paddock (listed 1 – 270) by location.

6. Salinity (measured as electrical conductivity EC1:5, dS/m) increased down the profile, with moderate levels of salinity (>0.80 dS/m) often seen below 60 cm (data not shown). There were some very high levels (>1.5 dS/m) detected in the Roma region and to a lesser extent in the St George and Banana regions These very high levels may be limiting plant growth if correlated with high chloride.

7. Chloride levels were low for most paddocks (>150 mg/kg), with levels increasing down the profile. However, there were paddocks detected with chloride above 300 mg/kg below 30 cm in the Goondiwindi, St George, Roma and Banana regions (data not shown), which is considered to impair root growth of intolerant crops (e.g. pulses).

8. Sodicity was detected in many of the paddocks (measured as exchangeable sodium percentage (ESP) with levels increasing down the soil profile (data not shown). Soils are considered sodic when ESP is greater than 6%, with ESP greater than 15% indicating a strongly sodic soil. Sodic soils are often dispersive, which can reduce water infiltration and limit a plant’s ability to extract water from soil. The Goondiwindi, St George and Brigalow regions had the highest ESP values. An ESP >15% was detected in 21% of paddocks (30-60 cm layer), 58% (60-90 cm) and 69% (90-120 cm).

9. Soil physical characteristics. The Emerson dispersion method showed poor structured (dispersive) soils occurred at varying rates across all geographical regions. St George, Goondiwindi and Brigalow had high rates of dispersive soil (58%, 54%, and 49% respectively) while Emerald was dominated by non-dispersive soils (94%) (data not shown). Dispersion was detected at different locations within the soil profile. As dispersion limits root growth, it was important to identify where the dispersion occurs in the profile to help understand the rooting depth of crops and from where soil water and nutrients can be accessed.

10. Soil biological data (measured via Predicta®B analysis, data not shown) indicated the most common pathogens to be those that cause crown rot, common root rot, white grain disorder, take-all, pythium root rot and charcoal rot. Interestingly, only 14 paddocks recorded levels over 2 Pratylenchus thornei g soil. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) varied greatly across paddocks with <1 kcopies DNA/g soil being detected in five paddocks, through to the highest reading of 634 kcopies DNA/g soil.

One grower (Brigalow) was interested to compare their long-term cropping soil (50+ years) to bordering remnant vegetation to understand the change in soil health over time. Some very interesting results were observed:

- TOC: 0–10 cm was 0.77% in the cropping versus 3.6% in the remnant vegetation. This indicates a loss of ~3% TOC in the surface soil layer.

- Phosphorus: Colwell P levels decreased from 90 mg P/kg in remnant vegetation to 23 mg P/kg under cropping (0–10 cm layer); and from 39 to 7 mg P/ha (10–30 cm layer). The BSES P similarly declined from 131 to 33 mg P/kg (0–10 cm layer) and from 66 to 16 mg P/kg (10–30 cm layer).

- Chloride: levels significantly decreased under cropping, from 1674 mg/kg under remnant vegetation down to 13 mg/kg after 50+ years cropping (30–60 cm layer).

Implications for growers

Comprehensive soil testing and analysis is a useful tool to determine soil health. It is important to take deep cores and analyse them incrementally in line with dryland cropping critical levels. However, once a paddock has been tested and analysed, changes other than N and soil biology will be slow. Future testing may only be worthwhile every five to 10 years. Additionally, by comparing paddocks and considering their differences, a deeper understanding of how soil health is affected by different land use management practices can be gained.

Total organic carbon levels are quite low on Queensland cropping soils. This data set confirms past research findings that levels decrease when native vegetation is replaced by cropping. These lower levels reduce the overall resilience of soils, particularly the amount of N and P which can be mineralised and become available to support crop growth. This means that higher levels of fertiliser are required to continue to maximise crop production. To maintain carbon levels, growers need to boost biomass production, i.e. grow the biggest crops as often as possible. This can be achieved by implementing the best possible agronomy.

A large proportion of soils have low levels of immobile nutrients, such as P and K, that may be impacting crop production. Continuing to remove P and K from subsoil (i.e. 10–30 cm) layers without replacement will exacerbate this situation. Growers should consider replacing P and K in this subsoil when levels drop below critical levels. Past research shows that applying deep P fertiliser can be highly profitable in depleted soils. However, responses can vary. Further research is underway to assess the risk/reward trade-off with farm data. Potassium is a different story. There has been very little research focused on K to accurately determine critical levels and develop clear recommendations to rectify deficiencies. More research is required. Current recommendations suggest applying test strips to identify responses.

References

Bell, M. (2023). Fertiliser deep banding factsheet.

Dalal, R. C., & Mayer, R. J. (1986). Long term trends in fertility of soils under continuous cultivation and cereal cropping in southern Queensland. I. Overall changes in soil properties and trends in winter cereal yields. Soil Research, 24(2), 265-279.

Natural Resources Conservation Service. (2024). Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Acknowledgements

The research presented within this paper would not have been possible without the support of growers and agronomists and investment from the Australian Government Landcare Fund and the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

This soil sampling was undertaken during the extraordinarily wet winter of 2022. It was all-hands -on-deck from the Regional Agronomy team to take advantage of the very small windows of ‘dry weather’ to take these soil cores. But the whole team’s perseverance and never-say-die attitude paid off. Not only did we get VERY good at taking soil cores from wet soil we have produced an exceptional dataset of grain cropping soils in Queensland. A big shout out to you all!

Contact details

Jayne Gentry

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Toowoomba

Email: jayne.gentry@daf.qld.gov.au

Date published

July 2024

® Registered Trademark