Agronomic practices for hyper yielding crop (HYC) years and environments

Agronomic practices for hyper yielding crop (HYC) years and environments

Take home messages

- The hyper yielding crops (HYC) project has successfully demonstrated new yield benchmarks for productivity of cereals in the more productive regions and seasons over the last four years

- At the HYC Wallendbeen site in 2022 and 2023, fungicide management strategies for stripe rust and Septoria control combined with variety choice was shown to be the most important factors in generating high yields

- Maximum wheat yields in southern NSW (Wallendbeen) were achieved by red grained feed wheats and modern fungicide chemistry

- Hyper yielding cereal crops require high levels of nutrition; rotations which lead to high levels of inherent fertility and judicious fertilizer application underpin high yields and the large nutrient offtakes associated with bigger crop canopies

- The most important agronomic lever for hyper yielding wheat and closing the yield gap over the last four years has been the correct disease management strategy which was important despite the drier spring in 2023.

Hyper yielding crops research and adoption

The Hyper Yielding Crops (HYC) project with assistance from three relatively mild springs (2020 – 2022) has been able to demonstrate new yield boundaries of wheat, barley and canola both in research and on commercial farms in southern regions of Australia with higher yield potential. Five HYC research sites with associated focus farms and innovation grower groups have helped establish that wheat yields in excess of 11 t/ha are possible at higher altitudes in southern NSW (Wallendbeen), in the southern Victoria and South Australian high rainfall zones (HRZ) (Gnarwarre and Millicent) and Tasmania (Hagley). In the shorter season environments of WA, 7–9 t/ha has been demonstrated at FAR’s Crop Technology Centres in Frankland River and Esperance.

Yield potential

Over the three years 2020 – 2022, the relative absence of soil moisture stress at HYC locations has allowed the project team to look more closely at yield potential from the perspective of solar radiation and temperature rather than soil water availability. High yielding crops of wheat and barley are about producing more grains per unit area in these mild moist springs. This has been demonstrated in several projects and is a key factor in producing very high yields. Whilst head number clearly contributes to high yield, there is a limit to the extent to which head number can be used to increase yield. In most cases with yields of 10 –15 t/ha, 500 – 600 heads/m2 should be adequate to fulfil the potential.

So how do we increase grains per m2?

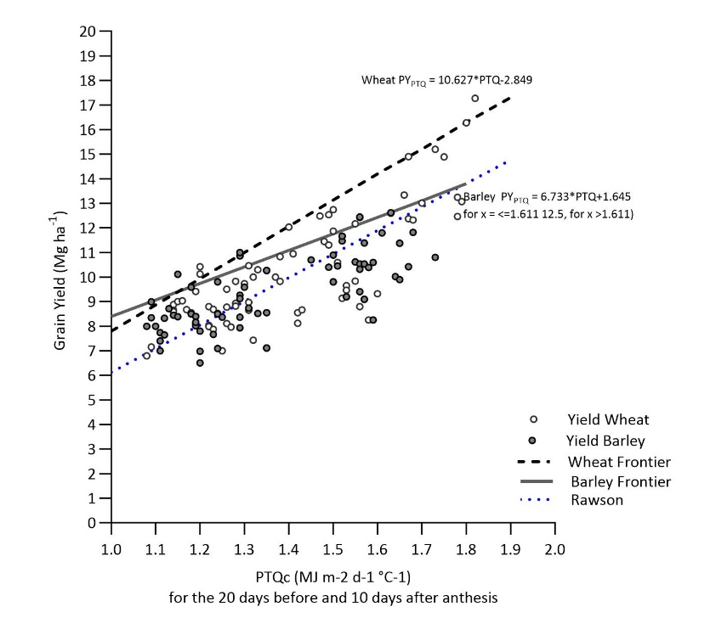

Whilst more heads per m2 contributes to yield outcomes, it is typically larger numbers of grains per head at harvest that generates high yields and increases the overall number of grains per unit area in HRZ regions. It’s been acknowledged for several years that increasing grain number is related to growing conditions prevalent in the period from mid-stem elongation to start of flowering (approximately GS33 – 61). This window of growth in cereals covers the period approximately three – four weeks (~300 °C days) prior to flowering and is described as the ‘critical period’ (Dreccer et al., 2018). This critical period encompasses when the grain sites are differentiating, developing and male and female parts of the plant are forming (meiosis). If conditions during this period of development are conducive to growth with high solar radiation and relatively cool conditions (avoiding heat stress), then more growth goes into developing grain number per head and therefore per unit area for a given head population. The Photothermal Quotient (PTQ) or ‘Cool Sunny Index’ is a simple formula (daily solar radiation/average daily temperature) that describes how conducive conditions are for growth and when applied to the critical period, it assists in determining the yield potential. When applied to the critical period a high PTQ means more photosynthesis for more days and more grain and more yield. The relative importance of PTQ is increased in seasons where soil moisture stress is not a factor (since soil moisture stress limits the ability of the crop to fill grain and fulfil its potential). HYC research has now been used to update the relationship between yield potential and PTQ (Figure 1). Using the graphed relationship established between yield and PTQ, it has been possible to demonstrate with HYC trial results that newer higher yielding European feed wheat varieties have resulted in a new upper yield boundary for given spring PTQ.

Figure 1. Relationship between photothermal quotient (PTQ) in the critical growth period and yield potential of cereals – a comparison of wheat and barley. Porker et al., (in press).

As growers and advisers, we are already aware of the importance of cereal flowering date in order to minimise frost risk and heat/moisture stress, however in high yielding crops where moisture and heat stress are less problematic, optimising the flowering date enables us to maximise growth in the critical period for generating grain number per unit area.

Realising yield potential

It is one thing to create yield potential by maximising grain number per unit area, however higher grain numbers established during the critical period still must be realised during grain fill. For example, a very late developing wheat variety could benefit from optimal growing conditions associated with a later flowering date and critical period i.e., longer sunny days that are not excessively hot. This might well maximise final harvest dry matter and growth during the critical period, but not the final grain yield as the crop does not have a sufficiently high photothermal quotient (PTQ) to maximise growth during grain fill post flowering (i.e., it’s too hot post flowering with later development and the crop has a low harvest index or soil moisture stress occurs during grain fill and there is insufficient soil water to finish the crop).

Nutrition and rotation for hyper yielding wheat – farming system fertility to establish yield potential

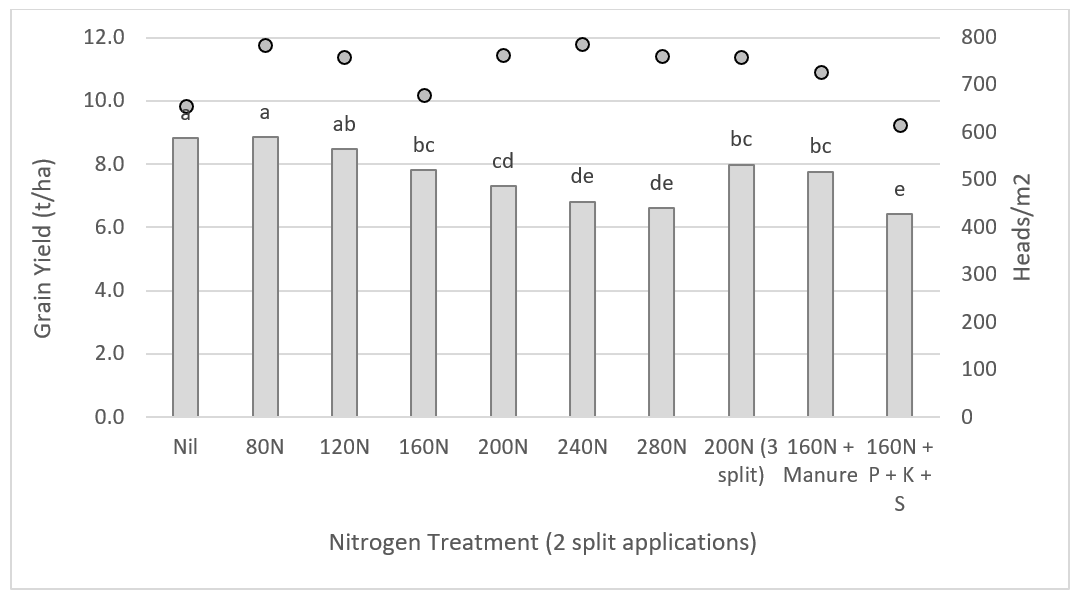

The most notable results observed in the HYC project to date relate to nitrogen fertiliser. However, simply applying high rates of N fertiliser is not always the best option to achieve hyper yields. Nitrogen fertiliser rates should consider (i) N mineralising potential of the soil, (ii) spared N from previous years, (iii) starting mineral N and other factors such as (iv) crop lodging potential that may impact radiation efficiency. It should be emphasised however that replacing N removal (N off-take in grain or hay) has to be an objective if we are to maintain a sustainable farming system. Results from our southern NSW site at Wallendbeen provide an example of the conundrum with hyper yielding wheat crops. Established in a mixed farming system based on a leguminous pasture (six year phase) in rotation with a six year cropping phase, winter wheat yielded 8–9 t/ha, however the application of N at rates greater than 120 kg N/ha (2022) and 160 kg N/ha (2023) in this scenario only served to reduce profit while higher rates ≥160kg N/ha also reduced yield in 2022 (Figures 2 & 3). In 2022 despite an application of plant growth regulator (PGR) Moddus® Evo at 0.2 L/ha + ErrexTM 750 at 1.3 L/ha at GS31, higher applied N fertiliser rates (above 160 kgN/ha) increase head numbers but also increased lodging during grain fill (data not shown) which led to reduced yield.

Figure 2. Influence of applied nitrogen, manure and other nutrients on yield and head number – HYC Wallendbeen, NSW 2022.

Columns denote grain yield and dots show heads/m2.

Notes:

N applied as urea (46% N) was applied at tillering (21 June) and GS31 (27 August)

Soil available N in winter (4 July): 0–10 cm 39 kg N/ha; 10–30 cm 56 kg N/ha; 30–60 cm 46 kg N/ha.

Chicken manure pellets applied at 5 t/ha with an analysis of N 3.5%, P 1.8%, K 1.8% and S 0.5%. Columns with different letters are statistically different P = 0.05, LSD: 0.79 t/ha

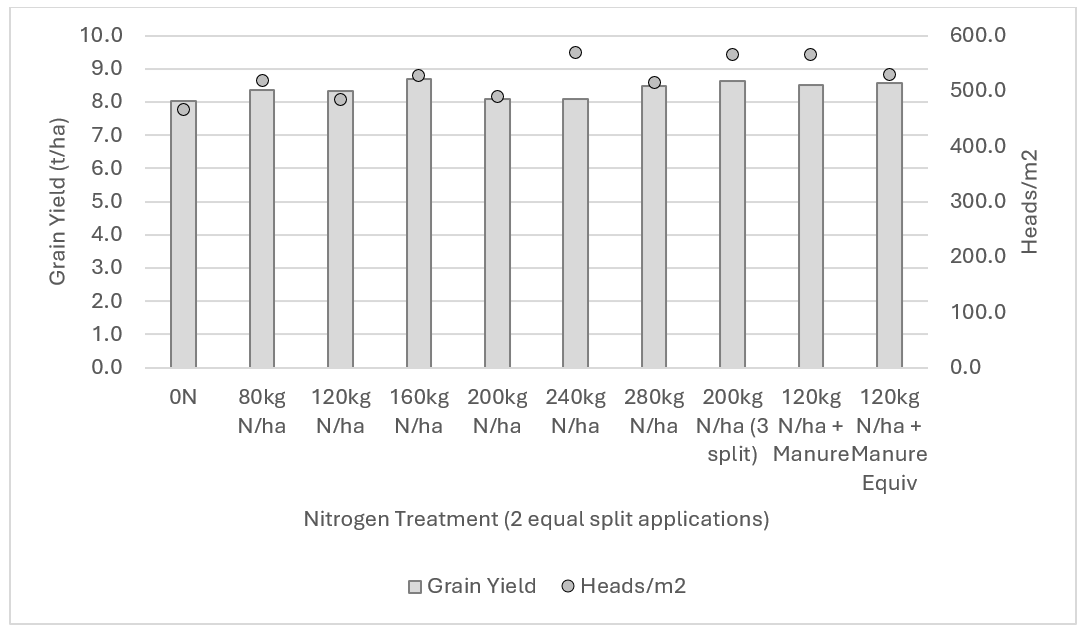

Figure 3. Influence of applied nitrogen, manure and other nutrients on yield and head number – HYC Wallendbeen, NSW 2023.

Columns denote grain yield (P = 0.142) and dots show heads/m2 (P =0.105).

Notes:

N applied as urea (46% N) was applied at GS30 (22 July) and GS32 (9 August)

Soil available N in winter (10 Jul): 0–10 cm 43 kg N/ha; 10–30 cm 70 kg N/ha; 30–60 cm 113 kg N/ha.

Cattle feedlot manure applied at 5 t/ha with an analysis of N 1.14%, P 0.68%, K 1.5% and S 0.4%.

Despite drier conditions in 2023 the results serve to illustrate that fertile soils with high soil N supply capacity have the potential to mineralise sufficient N to achieve potential yield. This is illustrated by the nil fertiliser rate in Figures 2 & 3. In fact, since 2016 in HYC research, optimum applied fertiliser N rates have rarely exceeded 200 kg N/ha for the highest yielding crops, even though the crop canopies (biomass) that these yields are dependent on are observed to remove far more N than that (assuming N is baled or burnt at harvest). This indicates N supply in the hyper yielding sites is most likely provided by the mineralisation of N from soil organic matter (SOM) pre-sowing and in-crop. The 8.0 t/ha (2023) and 8.8 t/ha (2022) yields from the nil N treatment are indicative of fertile farming systems, where N recovery efficiencies from SOM are typically much higher (70%, 2019 Baldock) than those achieved with fertiliser N which is often reported at 44% (Vonk et al., 2022; Angus and Grace 2017). Consequently, the same yield (8.8 t/ha) supplied entirely by N fertiliser would require 400 kg N/ha assuming an N efficiency of 44%.

Protecting yield potential

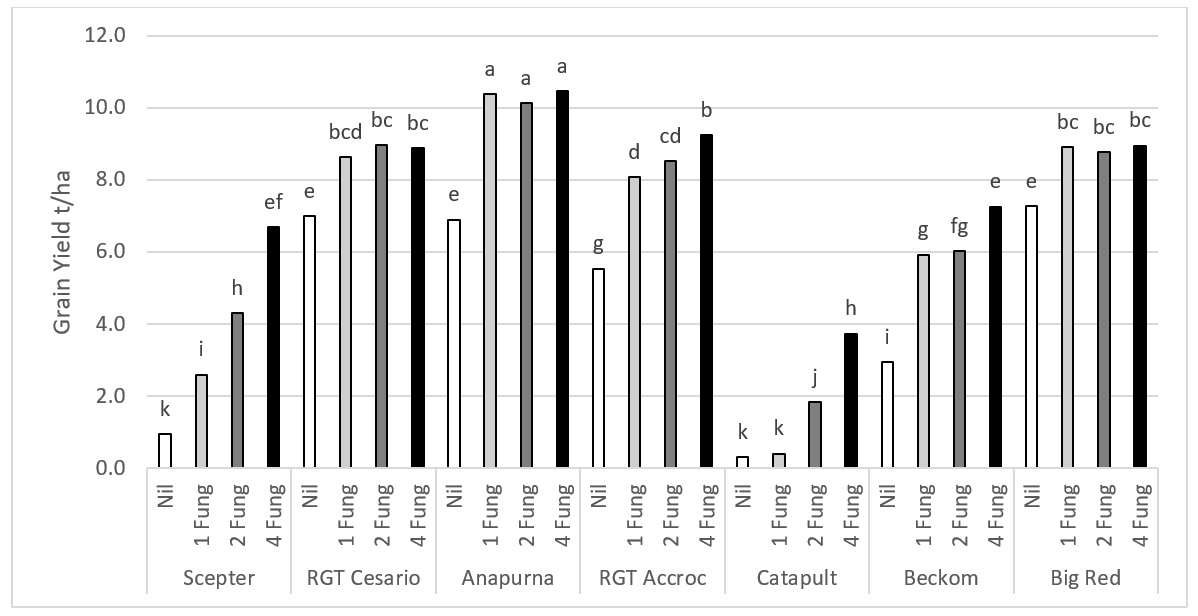

Many regions experienced just how important it is to protect yield potential in 2022, with many growers describing the stripe rust epidemic in 2022 as the worst in 20 if not 50 years. Disease management over the last four years has been shown to be one of, if not the most important factors in securing high yielding crops in HYC project trials. It has also been demonstrated to be one of the most important factors in securing high yields and closing the yield gap in favourable seasons in low to medium rainfall zones (L-MRZ). In Wallendbeen HYC trials in 2022 and the drier season of 2023 trials illustrated the importance of combining the best disease management strategy with the best germplasm (variety) (Figure 4). Seven wheat varieties (three milling wheats and four red grained feed wheats) were grown with four levels of fungicide protection (Table 1).

Table 1. Fungicide management treatments at Wallendbeen HYC, 2022 & 2023.

Treatment |

|

|---|---|

Treatment 1 | Untreated control |

Treatment 2 | One Unit approach, a single flag leaf fungicide applied at GS39 – Revystar® (mefentrifluconazole 100 g/L, fluxapyroxad 50 g/L) applied at 750 mL/ha (75g ai/ha & 37.5g ai/ha) |

Treatment 3 | Two-unit (straddle) approach at GS33 (3rd node) Revystar® (mefentrifluconazole 100g/L, fluxapyroxad 50g/L) applied at 750 mL/ha (75g ai/ha & 37.5g ai/ha); and GS59 (head emergence) Opus® 125 (epoxiconazole 125 g/L) applied at 500 mL/ha (62.5 g ai/ha) |

Treatment 4 | Four-unit approach combining at sowing flutriafol on the fertiliser (MAP) with three foliar applications – GS31 Prosaro® 420 (prothioconazole 210 g/L, tebuconazole 210 g/L) applied at 300 mL/ha (63g ai/ha of each ai); GS39 (flag leaf emergence) Revystar® (mefentrifluconazole 100g/L, fluxapyroxad 50g/L) applied at 750 mL/ha (75g ai/ha & 37.5g ai/ha); and GS59 (head emergence) Opus® 125 (epoxiconazole 125 g/L) applied at 500 mL/ha (62.5 g ai/ha) |

Treatment 5 | Three-unit approach combining at sowing flutriafol on the fertiliser (MAP) with a two spray straddle at GS33 (3rd node) Revystar® (mefentrifluconazole 100 g/L, fluxapyroxad 50 g/L) applied at 750 mL/ha (75g ai/ha & 37.5g ai/ha).; and GS59 (head emergence) Opus® 125 (epoxiconazole 125g/L) applied at 500 mL/ha (62.5 g ai/ha). |

Table 2. Dates for key stages of crop phenology for spring and winter wheat varieties in the Wallendbeen HYC trial in the cool and very wet season of 2022 and drier and warmer season of 2023.

Year | Wheat type | GS31 | GS33 | GS39 | GS59 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2022 | Spring | 14-Jul | 9-Aug | 26-Aug | 20-Sep |

Winter | 26-Aug | 20-Sep | 3-Oct | 30-Oct | |

2023 | Spring | 3-Jul | 2-Aug | 17-Aug | 10-Sep |

Winter | 9-Aug | 4-Sep | 19-Sep | 2-Oct |

With the principal diseases being stripe rust and Septoria tritici blotch caused by the pathogens Puccinia striiformis f.sp. tritici and Zymoseptoria tritici, respectively, the levels of infection in 2022 at this site were so severe that not even the four-unit approach to disease management gave full control in the more stripe rust susceptible varieties. In 2023 the levels of disease were more typical with much smaller fungicide responses which were however still very cost effective in susceptible varieties. In 2022 none of the varieties had sufficient genetic resistance to be farmed more profitably with no fungicides, whilst in 2023 that was the case with AGTW005 (unfortunately this feed wheat was not commercialised after four years of testing). In Scepter, the response to the four-unit approach was almost 6 t/ha in 2022 (Figure 4) and 1.9 t/ha in 2023 (Figure 5). In 2022 the varieties Anapurna, RGT Cesario and Big Red showed no significant yield advantage to four units of fungicides compared to one. With RGT Cesario, stripe rust resistance was not complete and a spray at GS31 did reduce disease levels. It should be noted that with these high yielding feed wheats, the response to fungicide was still 1.5 – 3.0 t/ha.

Whilst fungicides can only be considered an insurance (i.e., we don’t know what the economic return will be when they are applied), it is clear that when conditions are wet during the stem elongation period as the principal upper canopy leaves emerge (flag, flag-1, flag-2), fungicide application is essential to protect yield potential. Infection was so severe in 2022, that fungicide timing and the strength of the active ingredients being used made significant differences in productivity. Long ‘calendar gaps’ of over four weeks between fungicides (as was the case in own our study) resulted in the epidemic becoming out of control in many crops, as unprotected leaves became badly infected in the period between sprays and applications became more dependent on limited curative activity rather than protectant activity. The wider issue the success of fungicide management raises is that pathogen resistance to fungicides is primarily driven by the number of applications of the same mode of action. This is why it is imperative for HYC research to incorporate the most resistant, high yielding and adapted germplasm available in order to reduce our dependence on fungicide agrichemicals.

Figure 4. The influence of the number of applied fungicide sprays on grain yield of different varieties at the HYC trial at Wallendbeen, NSW 2022. All varieties presented are protected by plant breeder’s rights.

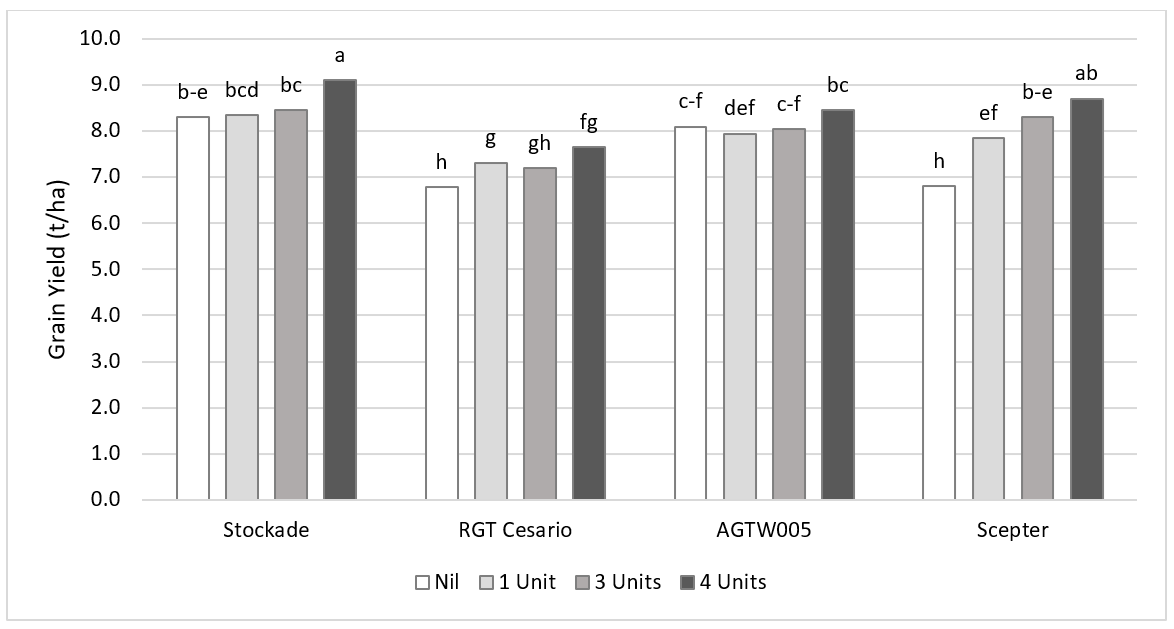

Figure 5. Influence of fungicide strategy on grain yield (t/ha) of wheat cultivars at the HYC trial at Wallendbeen, NSW 2023.

P value=0.001, LSD (P = 0.05) = 0.47.

References and further reading

Angus JF and Grace PR (2017) Nitrogen balance in Australia and nitrogen use efficiency on Australian farms. Soil Research. 55(6), 435-450.

Baldock J (2019) Nitrogen and soil organic matter decline - what is needed to fix it? GRDC Update Paper.

Dreccer MF, Fainges J, Whish J, Ogbonnaya FC, Sadras VO (2018). Comparison of sensitive stages of wheat, barley, canola, chickpea and field pea to temperature and water stress across Australia. Agric. For. Meteorol. 248, 275–294.

Peoples MB, Swan AD, Goward L, Kirkegaard JA, Hunt JR, Li GD, Schwenke GD, Herridge DF, Moodie M, Wilhelm N, Potter T, Denton MD, Browne C, Phillips LA and Khan DF (2017) Soil mineral nitrogen benefits derived from legumes and comparisons of the apparent recovery of legume or fertiliser nitrogen by wheat. Soil Research 55, 600-615.

Porker K, Poole N, Warren D, Lilley J, Harris F & Kirkegaard J (in press) *Field Crops Research* (under review in special issue).

Vonk WJ, Hijbeek R, Glendining MJ, Powlson DS, Bhogal A, Merbach I, Silva JV, Poffenbarger HJ, Dhillon J, Sieling K and ten Berge HFM (2022) The legacy effect of synthetic N fertiliser. European Journal of Soil Science. 73.

More results from previous HYC research can be found on the FAR website.

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of these projects is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the authors would like to thank them for their continued support. FAR Australia gratefully acknowledges the support of all research and extension partners in the Hyper Yielding Crops project. These are CSIRO, the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD) in WA, Brill Ag, Southern Farming Systems (SFS), Techcrop, the Centre for eResearch and Digital Innovation (CeRDI) at Federation University Australia, MacKillop Farm Management Group (MFMG), Riverine Plains Inc and Stirling to Coast Farmers.

Contact details

Nick Poole

Field Applied Research (FAR) Australia

Shed 2/63 Holder Rd, Bannockburn, Victoria 3331

Phone: 03 5265 1290

Mb: 0499 888 066

Email: nick.poole@faraustralia.com.au

Tom Price

Field Applied Research (FAR) Australia

Shop 12, 95-103 Melbourne St, Mulwala, NSW 2647

Mb: 0400 409 952

Email: tom.price@faraustralia.com.au

Date published

August 2024

Varieties displaying this symbol beside them are protected under the Plant Breeder’s Rights Act 1994.

® Registered trademark

TM Trademark

GRDC Project Code: FAR2004-002SAX, FAR1506-001RTX,