How can nitrification inhibitors increase the effectiveness of nitrogen application and what other strategies are available

How can nitrification inhibitors increase the effectiveness of nitrogen application and what other strategies are available

Author: Ashley Wallace, Malcolm McCaskill, Roger Armstrong (Agriculture Victoria), Adam Hancock (Elders Rural Services) | Date: 22 Aug 2024

Take home messages

- Substantial gaseous losses of nitrogen (N) derived from fertiliser can occur in certain soil types and seasons (particularly poorly structured soils that are prone to waterlogging).

- Commercially available fertiliser formulations containing nitrification and urease inhibitors can reduce these losses but attract a price premium.

- Inhibitor effectiveness varies with soil type and season, so understanding where and when to use them is critical to improving profitability.

- Considering the use of inhibitors as part of the broader ‘4 R’s’ fertiliser management approach is important.

Background

Nitrogen (N) fertilisers are one of the largest variable cost inputs for grain growers, especially in medium and high rainfall environments. N management is also one of the biggest single ‘levers’ that grain growers have in their toolbox for maximising profitability and managing seasonal risk. However, applying N fertiliser brings with it the risk that some of the investment will be lost to the environment due to a range of processes which vary with soils, management and seasonal conditions (Figure 1). Conditions that are ‘too dry’ following surface application of urea can lead to both poor utilisation by the target crop, as well as gaseous N loss due to ammonia volatilisation. Conversely, conditions that are ‘too wet’ following application can lead to N loss due to leaching, surface runoff or denitrification. While the available evidence suggests that, on average, 22% of the N applied to grain crops in Australia is lost in the year of application (Angus and Grace 2017), these values can vary widely (near zero to over 90%). The good news is that there are strategies available to help increase utilisation by the crop and reduce such losses, but their successful application requires an understanding of your individual farming system and the risks of various N loss pathways to inform economic analysis.

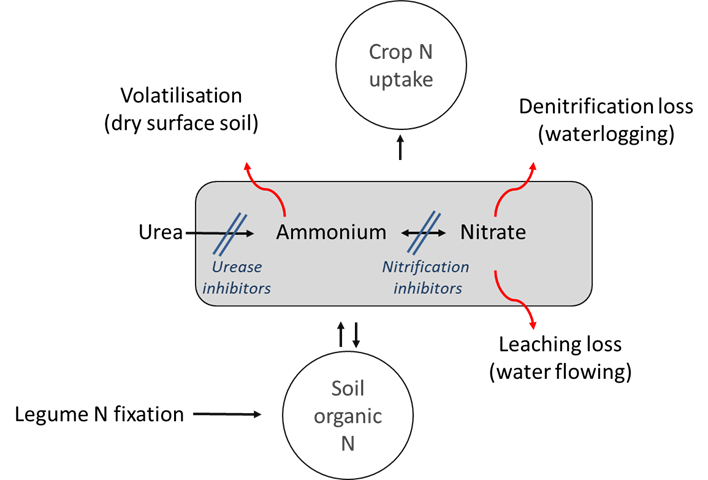

Good fertiliser management can be guided by the ‘four R’s’ principle: right rate, right time, right placement and right product. Regarding product choice, there are a number of enhanced efficiency fertiliser products on the market which can target different loss pathways and improve nitrogen use efficiency (NUE). These products were mostly developed decades ago and have been utilised commercially in Europe, North America and New Zealand, often in response to government or supply chain policies. In Australian cropping systems, the majority of N is applied as urea, which is cost effective and soluble, but not plant available, requiring conversion to ammonium prior to crop uptake. Treating urea with urease inhibitors, such as NBPT (for example, Green Urea NV®) slows the conversion of urea into ammonium (Figure 1). In doing so, this slows crop access to the applied N, but also reduces the risk of ammonia volatilisation under temporarily dry conditions, thereby allowing more time for rainfall to ‘wash’ the urea into the soil.

In situations where soils are prone to wet or waterlogged conditions, addition of nitrification inhibitors, such as DMPP or nitrapyrin (for example, eNpower® and eNtrench®), to urea can help to reduce loss of N to denitrification, leaching or runoff by maintaining fertiliser N in the ammonium form (plant available). It is worth noting that surface application of nitrification inhibitor-treated fertilisers can inadvertently increase the risk of volatilisation loss under dry conditions, by maintaining N as ammonium (Lam et al. 2017). As a result, it is important to consider the conditions that are likely to follow fertiliser application and target their use to specific risks. Because, in Australia, there is currently no legislative requirement to reduce N losses, the ‘economics’ of using these products will depend on the likely magnitude of losses resulting from a specific mechanism (denitrification, volatilisation or leaching) and how effective these products are in reducing these losses (which includes how long they remain ‘active’), combined with the relative crop response to any ‘saved’ N.

Figure 1. Basic N cycle showing major inputs, losses, pools and processes driving N availability in cropping systems. Potential intervention points for use of inhibitors are also shown in italics and grey highlight shows plant available forms of N.

Discussion

Inhibitor-treated fertiliser can reduce loss of applied N

Field trials undertaken in western Victoria and south-east SA show that the use of nitrification inhibitor-treated urea can help to reduce loss and increase uptake of applied N (Hancock 2023, Harris et al. 2016, Wallace et al. 2020). However, the effectiveness of using these inhibitors in increasing grain yields (and quality) and reducing losses depend on the environment, soil type and seasonal conditions at the time of application. Nitrification inhibitors slow the conversion of N from ammonium to nitrate (Figure 1), typically over a period of 1–2 months, depending on conditions (Chen et al. 2010). In doing so, they can help avoid denitrification associated with poorly aerated soils (for example, waterlogged situations, particularly where soil structure is poor) or leaching on coarse texture/sandy soils.

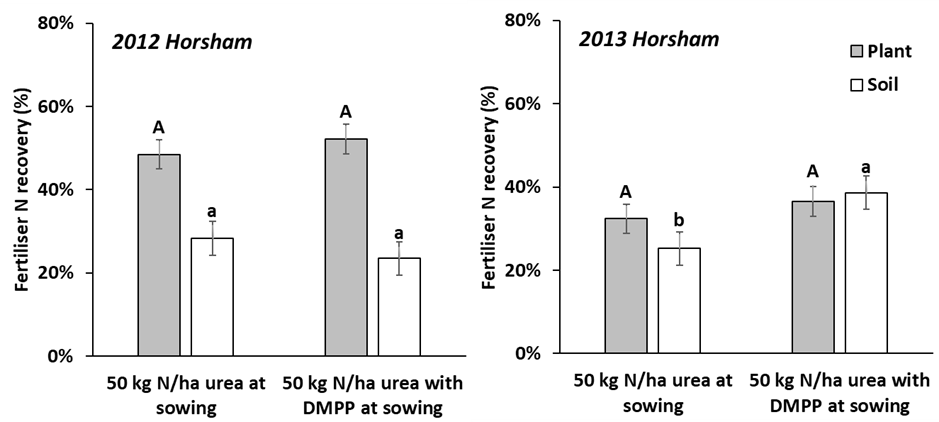

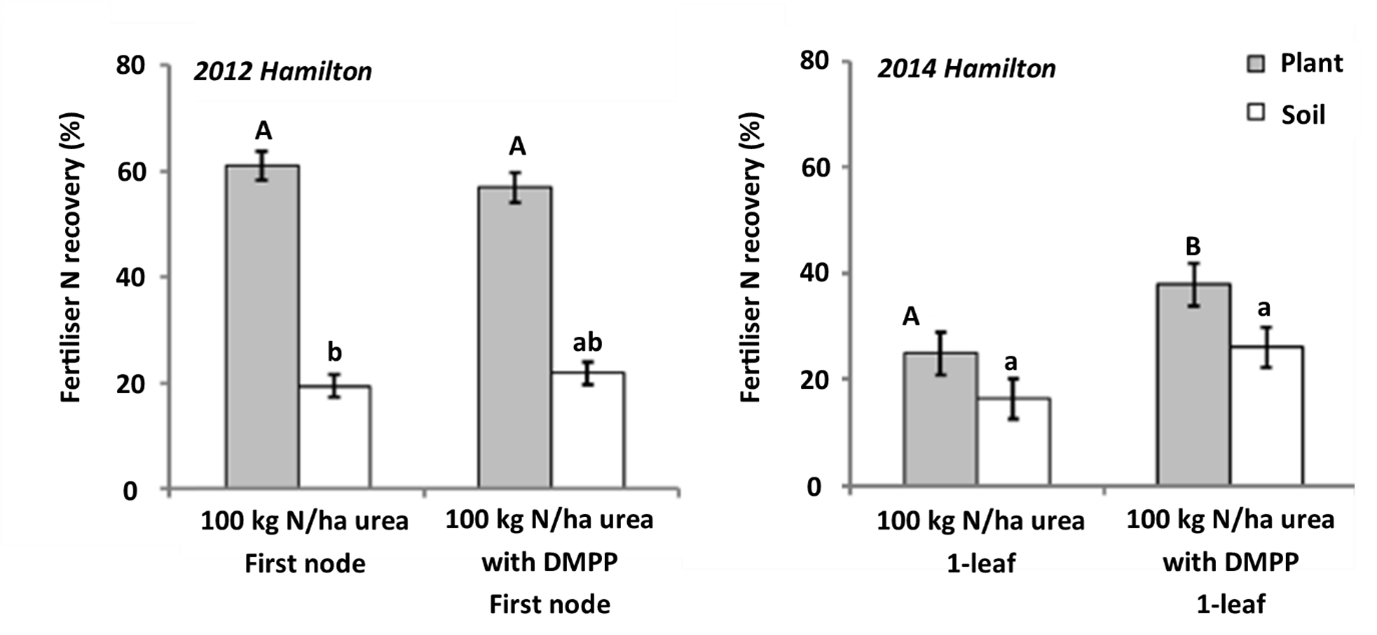

Trials conducted in the Wimmera from 2012 to 2014 found that, when N was applied at sowing (well prior to peak crop demand), addition of DMPP only reduced loss of fertiliser N by retaining more N in the soil when winter rainfall was above average in 2013 (decile 6 growing season versus decile 3 in 2012 and decile 1 in 2014, Figure 2, Wallace et al. 2020). A similar study, conducted at Hamilton under higher rainfall conditions, showed that urea top-dressed to wheat around the one-leaf stage shortly after emergence resulted in 60% loss of N, compared with a 35% loss for DMPP-treated urea. This highlights the potential benefit of DMPP addition when fertiliser is applied well ahead of crop demand and prior to waterlogging (Figure 3, Harris et al. 2016). Conversely, where urea was top-dressed at the first node growth stage, with a shorter lag between application and plant uptake, loss of N was reduced and there was no benefit from adding DMPP.

Figure 2. Recovery of N in plant and soil for urea applied to wheat at Horsham in 2012 and 2013. Urea was applied below the seed at sowing with and without addition of DMPP nitrification inhibitor (Wallace et al. 2020). Bars indicate least significant difference (P<0.05), and letters indicate significant differences.

Figure 3. Recovery of N in plant and soil for urea applied to wheat grown at Hamilton in 2012 and 2014 with varying timing and addition of DMPP nitrification inhibitor (Harris et al. 2016). Bars indicate least significant difference (P<0.001), and letters indicate significant differences.

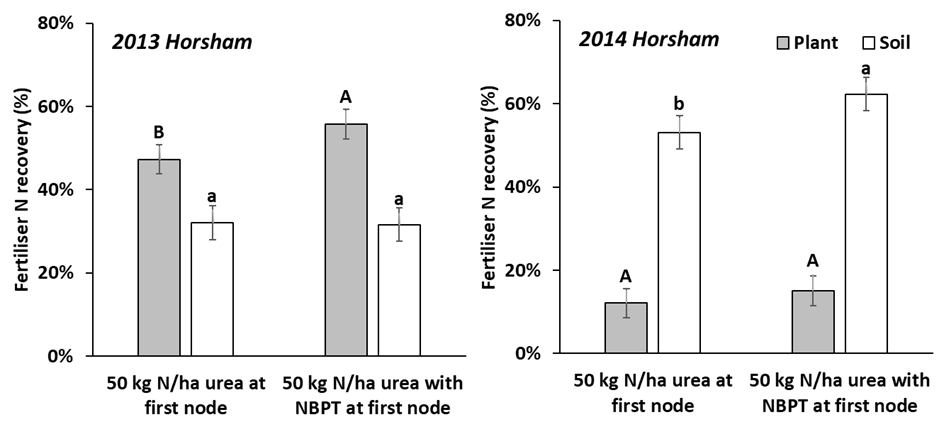

Inhibitor-treated fertiliser can also help to avoid volatilisation loss associated with insufficient rainfall following surface application, especially on alkaline topsoils (pH >8). Urease inhibitors, such as NBPT, slow the conversion of urea into ammonium (Figure 1, Turner et al. 2010). In doing so, this allows more time for a rain front to effectively wash urea into the soil, thereby reducing the potential for loss. As a result, these products are typically targeted at drier environments, such as the northern Wimmera and the Victorian/South Australian Mallee. Field trials undertaken in the Wimmera have shown potential to reduce loss of applied N under both wet and dry conditions (Figure 4). At Horsham in 2014, adding NBPT to urea applied at the first node growth stage in wheat significantly reduced loss of applied N, retaining more N in the soil when rainfall following application was minimal (less than 40 mm from August to October). Conversely, in a wetter season (2013), where over 160 mm was received from August to October, the risk of denitrification increased. In this case, addition of NBPT slowed both urea hydrolysis and, by extension, nitrification of ammonium, thereby reducing losses associated with wetter conditions, increasing crop uptake of applied N (Wallace et al. 2020).

Figure 4. Recovery of N in plant and that remaining in the soil following urea applied to wheat at Horsham in 2013 and 2014. Urea was top-dressed at first node with and without addition of NBPT urease inhibitor (Wallace et al. 2020). Bars indicate least significant difference (P<0.05),and letters indicate significant differences.

Improvements in crop yield are typically smaller than reductions in N loss

Reviews of studies internationally show that nitrification and urease inhibitor-treated fertilisers can improve nitrogen use efficiency (NUE), increase the amount of N taken up by the crop and improve productivity. However, improvements in NUE (average of 12%) are often greater than increases in crop yield (approximately 10% for urease inhibitors and 5% for nitrification inhibitors (Abalos et al. 2014). Similarly, the local studies outlined above showed limited yield response to the use of inhibitors despite showing potential to reduce loss. For the trial conducted at Horsham in 2013, adding NBPT to urea applied at first node increased yield from 4.2t/ha to 4.7t/ha. However, trials conducted at Hamilton showed limited yield response to N addition regardless of inhibitor use. This was likely the result of substantial background soil N levels and high rates of in-season mineralisation. Meanwhile, a field trial undertaken at Kybybolite on an N responsive soil showed that addition of DMPP to urea that was top-dressed after a waterlogging event increased N recovery but had limited effect on yield compared to urea alone (Hancock 2023). In this case, the greatest benefit came from altering the timing of urea application, with higher yields achieved where one third of the fertiliser was applied after waterlogging rather than before. It is also important to note that nitrification inhibitors work by reducing microbial activity. Current commercially available inhibitors have a limited life in wet soils with high levels of organic matter (microbial activity), with few being effective for more than a few weeks under these conditions.

These findings highlight that ultimately, the most important decision that you make as a grower is whether to apply N and when application should occur. In most Australian grain production systems, N fertiliser provides a ‘top-up’ N supply (data from the Wimmera indicated that fertiliser supplied an average of 16–35% of total crop N needs, Wallace et al. 2020), filling gaps where soil N is unable to provide enough to support the target or water-limited yield. However, when considering the potential benefit of inhibitor use, decreases in fertiliser N loss can often be masked by a relatively modest yield response to N. For example, consider a wheat crop yielding around 5t/ha. Applying the 40kg N/t rule of thumb suggests an overall N requirement of 200kg/ha. If this requires fertiliser input of 50kg N/ha and adding an inhibitor increases crop N uptake by 15%, this is equivalent to 7.5kg N/ha. In most situations, it would be difficult to measure a significant improvement in yield from an additional 7.5kg/ha. As a result, significant yield responses to inhibitor use often require significant rates of N loss, coupled with a strong underlying yield response to N addition, plus using the appropriate inhibitor and timing of application.

It is also worth noting that the majority of trials testing inhibitors are conducted for a small number of N rates. This is important when considering the economics of a yield response. For example, if the price premium on an inhibitor is in the range of 15% and it is possible to obtain a similar or slightly increased yield with a 15% or more reduction in N rate, then their use could be profitable. While studies have been conducted to address the shortage of evidence, further trials are needed to test the fine tuning of fertiliser rates to achieve economic responses with inhibitors.

We can’t predict the season, so how can we apply this knowledge

Successful application of inhibitors requires them to be targeted at situations where they are most likely to offer benefit. The starting point with any N decision is whether or not to apply N and this comes back to a well-considered N budget. Soil testing, paddock history, yield and/or protein mapping and seasonal outlooks can all assist with deciding the approximate rate and timing of N required for a given crop and target yield. Fine tuning this to account for poorly drained areas of the farm, considering their yield and N-response potential can further help to manage N losses by avoiding excess N application when crop demand is low. When considering the use of nitrification inhibitors, the next key question to ask is whether you expect a prolonged period of wet (possibly waterlogged) soil conditions following application and whether this is likely to impact yield potential. Long-term rainfall records, supported by seasonal forecasts, can be a useful tool in answering this question.

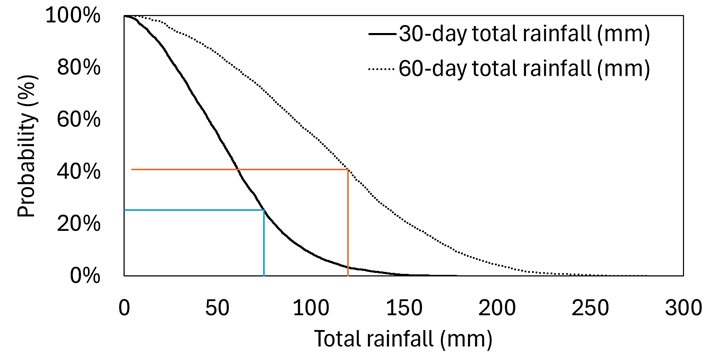

For the purpose of this paper, an analysis was undertaken of long-term records from the Bureau of Meteorology station at Naracoorte (Figure 5). This simplified analysis shows that, historically, there is a 25% chance of any 30-day period from April to October receiving at least 75mm of rainfall. This increases to over 40% for a total of at least 120mm over any 60-day period. While these totals and their impact on waterlogging risk will change across the landscape, they nonetheless help to quantify the likelihood of waterlogging and can be adapted with local knowledge to identify environments and soils at most risk of N loss.

Figure 5. Probability of exceeding a certain rainfall total over any 30-day or 60-day period between April and October at Naracoorte, based on observations from the Bureau of Meteorology (1969–2023, www.bom.gov.au).

A theoretically ‘nitrification inhibitor responsive’ crop might be one that required fertiliser prior to a prolonged period of wet soil conditions during tillering but did not undergo waterlogging substantial enough to reduce tiller number. This crop may therefore maintain its yield potential, while having been subject to substantial loss of N from the soil. In doing so, it is possible that the crop may obtain a yield benefit from the ‘saved’ N, ideally resulting in a return on the price premium. In this way, inhibitors may also help to solve logistical constraints around timing of N application where trafficability is poor through much of the season, limiting top-dressing opportunities during tillering and early stem elongation. At the farm level, it may also be possible to consider spatial management of inhibitor use. A field trial conducted at Glenthompson in 2017 showed that spatial variation in drainage within a paddock can lead to significant differences (up to 22%) in fertiliser N loss (McCaskill 2023). While the underlying yield potential of poorly drained areas may be lower, spatial application of inhibitor-treated fertilisers to target high risk areas may present an opportunity to close the gap between yield zones, although trial work on this topic is currently limited.

Conclusion

Inhibitor-treated fertilisers can help to increase the NUE of fertiliser application, reducing loss and increasing crop uptake. However, this varies with soil conditions following application. In the case of nitrification inhibitors, improvements are favoured by prolonged periods of wet or waterlogged soil conditions and low crop N demand. Yield responses to inhibitor use are less consistent, requiring a strong underlying yield response to N, coupled with high rates of N loss. While the economics of inhibitor use depend on either yield gains, or potential reductions in application rate to offset their additional cost, there is currently a lack of studies investigating wide ranges of N rate with inhibitors to help ‘fine tune’ their application. Additionally, while studies have shown that inhibitors can be effective, further local testing over multiple years would be of benefit. Such trials would allow consideration of seasonal differences and potential benefits of increased fertiliser N retention over multiple years.

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the authors would like to thank them for their continued support. Thanks also to Agriculture Victoria, the South Australian Grains Industry Trust and the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry for funding.

References

Abalos D, Jeffery S, Sanz-Cobena A, Guardia G, Vallejo A (2014) Meta-analysis of the effect of urease and nitrification inhibitors on crop productivity and nitrogen use efficiency. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 189, 136-144.

Angus JF, Grace PR (2017) Nitrogen balance in Australia and nitrogen use efficiency on Australian farms. Soil Research 55, 435-450.

Chen D, Suter HC, Islam A, Edis R (2010) Influence of nitrification inhibitors on nitrification and nitrous oxide (N2O) emission from a clay loam soil fertilized with urea. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 42, 660-664.

Hancock A (2023) Nitrogen strategies for HRZ wheat in waterlogged soils and denitrification – final report project ELD-03422-R. SAGIT

Harris RH, Armstrong RD, Wallace AJ, Belyaeva ON (2016) Delaying nitrogen fertiliser application improves wheat 15N recovery from high rainfall cropping soils in south eastern Australia. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 106, 113-128

Lam SK, Suter H, Mosier AR, Chen D (2017) Using nitrification inhibitors to mitigate agricultural N2O emission: a double-edged sword? Global Change Biology 23, 485-489

Turner DA, Edis RB, Chen D, Freney JR, Denmead OT, Christie R (2010) Determination and mitigation of ammonia loss from urea applied to winter wheat with N-(n-butyl) thiophosphorictriamide. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 137, 261-266

Wallace AJ, Armstrong RD, Grace PR, Scheer C, Partington DL (2020) Nitrogen use efficiency of 15N urea applied to wheat based on fertiliser timing and use of inhibitors. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 116, 41-56

A nitrogen reference manual for the southern cropping region – GRDC 2020

Contact details

Ashley Wallace

Agriculture Victoria

110 Natimuk Rd, Horsham VIC 3400

ashley.wallace@agriculture.vic.gov.au

GRDC Project Code: DAV00125, DAV1607-004BLX,