Succession planning - the do's and don'ts of family succession

Succession planning - the do's and don'ts of family succession

Author: Andrew Beattie | Date: 12 Aug 2014

Andrew Beattie,

ProAdvice Pty Ltd.

Keywords: succession planning, family farming, communication, formal agreement.

Take home messages

- Succession and estate planning in a family farming business is a complex juggling of the needs and wants of the “retiring” generation, the new farmer(s) and their partners and often siblings of the new farmers who will not be farming in the future. In addition to this there is generally a long multi-generational family history, family members at different ages and stages, a large asset with low and variable return, and a “spoonful of emotional baggage” just to increase the complexity.

Introduction

This paper and presentation will examine aspects of succession planning using a case study and the presenter’s experience, with a view to providing a practical frame work for a successful succession and estate planning process including tips on the do’s and don’ts of succession and estate planning in family farming businesses.

These include:

- Separate the succession and estate plans.

- People matter most; set the ground rules and guiding principles for decision making. Start with needs and objectives.

- Time frame is important. i.e. do it early, take your time and don’t barge through.

- Allow for a balance of flexibility and certainty.

- Ensure education on the future implications of the plans.

- Go through and understand the “What ifs”; all the D words : death, divorce, disagreement, disability.

- Formal agreements are vital; deed of family arrangements.

- Succession is a process or a journey not a destination.

Overview of succession and estate planning in primary production

Succession and estate planning in any business is a complex process that requires good communication, planning and ideally a long lead in time to maximise the chance of a successful transition. A family farming business adds to this complexity due to the following reasons:

- The emotional nature of family connections and the associated difficulty in having conversations about these difficult subjects;

- often only some of the next generation will be involved in the future running of the business and others children are not. These individual family members are generally at different ages and life stages;

- the older generation will often still be involved in the operations of the business. There are varying needs and wants of the “retiring” generation as compared to the new farmer(s) and their partners;

- there is often long multi-generational family history of the land and business in question. Maintaining a viable farm in the family is often a key objective and can conflict with other objectives; and

- the farm is a large tangible asset with a value that is independent of the operational return of the business. The business return on the asset value is generally low and variable (relative to other investments). A large asset is therefore required to have a viable farming unit. The farm usually makes up the majority of the family wealth. The combination of all of these factors makes it very difficult to “pass on” a viable farming business and have an equal or even fair distribution of the family assets.

Changes in succession and estate planning culture

Over the last century or so there has been a marked change in society’s perception of a fair process of succession and estate transfer. In the past the stereotypical farm succession process was:

The oldest (or strongest) son took over the family farm or family estate;

if possible other sons who wished to farm were helped to get established in other farming regions being “opened up”; and

daughters where left smaller “tokens” of the family wealth.

Today there is more often an expectation that family assets are divided equally, males and females have equal opportunity, and all this is backed up by law where the courts can override wills.

While no one can deny there is a good case for equality of entitlement, the process in my opinion is speeding up the decline in the number of family farm operations. For a given enterprise type the size of farm required for a viable operation is much larger than it was 10, 20 and 30 years ago. As such there are two competing factors at play:

- Modern estate planning is leading to smaller farms, or farms with heavy debt burdens, via division of assets or sale of the farm because “fair” division is not possible; and

- the scale required for a viable operation is increasing.

Data shows the number of broad acre farms halved from 1977-78 to 2006-07 (Sheng et al 2011), and the most recent data (Australian Bureau of Statistics data) shows there has been a 13% drop in the total number of farms in the five years to 2011.

This is not saying that either past or the present are right or wrong, rather it is the environment in which businesses operate. As such, a family who want to succeed a viable farm to the next generation, together with a fair distribution to other siblings, needs to have a long and careful planning and implementation process to increase the likelihood of success.

Communication on succession and estate planning

Research indicates that the level of communication on succession and estate planning within small businesses is pretty poor. While the research statistics on succession in farming business is now pretty old and therefore its relevance could be questioned, it does, however, give some historical perspective and some guidance to what professionals, active in providing successional advice, see.

Communication

The data on the level of succession communication that occurs in the farming community is quite damming:

- For the main farmer (usually male)

- 30% - 42% have not discussed succession with spouse;

- 50% - 63% have not spoken to farm based children;

- 82% have not spoken to daughter-in-law. (1 study); and

- 60% of second generation have not spoken to their spouse (1 study).

Sources: Gamble et al (1995), Crosby (1998), Barclay et.al. (2007).

Is this the same today? Experience suggest that there has been some improvement as there has been significant exposure of the issue, many seminar sessions and opportunities to build awareness of the need to tackle the issue. However, the improvement has been low and lack of succession communication before an “issue” has arisen is still a major barrier to successful successional outcomes.

A key message: Don't be one of these statistics.

Why the poor statistics.

People do not communicate about succession for a number of reasons. Experience suggests it is due to one or a combination of the following reasons:

- It involves emotional discussion and the “main players” are men; most men and particularly males that are farmers are particularly poor at discussions involving emotion;

- potential parties to a discussion can’t see a solution to meet everyone’s needs so they “bury their head in the sand”; and

- it is not urgent so the urgent activities take over.

The result of these poor statistics

Due to the statistics listed above, succession is finally raised when:

- Someone is frustrated and “had enough” – disagreement; and/or

- there has been an “event” such as – death, disability or divorce.

The lack of early, constructive communication and planning on succession results not only in disagreement between family members and personal stress, it also leads to business underperformance and potential erosion of family wealth. This is backed-up in the literature:

- This issue is the most underrated impediment to business performance. From my experience, differences between generations and siblings can stall business development for a decade or more, until the issue is resolved (Elaine Barclay, 2007).

- Lyn Sykes (a renowned succession facilitator) estimated there is an average 20% drop in productivity during periods of unresolved issues and conflict surrounding succession.

- Lack of purposeful planning and open communications will result in a significant and direct financial loss, not only to individual farming families, but also to Australian primary industry as a whole (Rural Law Online forum, 2005).

- Perhaps most importantly the forum postings highlighted the emotional trauma, financial loss and the often irrevocable damage sustained to family relationships, which can occur where planned succession is not an integral part of managing the farming business (Farm Succession planning – Rural Law online Forum - Dec 2005 report - 6000 visitors accessed 31,600 times).

Key message:

- Don't be one of these damming statistics.

- Don't leave it until there is frustration or an ‘event’.

- Do get help if communication is ‘not your best skill’.

Case study

The following case study is based on an actual succession and estate planning processes. Some ‘details’ have been changed for privacy purposes.

Historical background

Early 2000s

- Family farming operation - Parents = 4th generation of farmer on that farm.

- 2 children (5 years age difference) - both have worked on the farm from time to time after finishing education.

- A moderately viable farm – (effectively just paying wages) with some off farm assets and reasonable equity.

- One child has been full time on farm for five years and now effectively running the farm, other child has been off farm pursuing other careers and not looking like being a farmer.

- Parents slowing down and spending less time on farm.

- Children married – next generation of children (grandchildren) starting.

- Farming child wants to know what the future holds for himself and his family and started agitating for succession to be discussed and for some certainty for the future defined.

- All agree to a succession planning session with an independent facilitator and the business’s professional advisers.

Mid 2000s

Succession Plan –2005

A succession meeting is held with a facilitator and the business accountant is also present. At this meeting an overall succession and estate plan is devised and agreed to.

Meeting minutes

- The objective was for security for the parents, a viable farm for the farmer and a fair and reasonably equal distribution of family assets.

- Farm business would be taken over by farming child. The current non farming child didn’t believe they wanted to farm – succession of management done – easy.

- Farming child would need to partially fund parents’ retirement (defined amount) into the future and any future age care needs (ill-defined).

- The majority of farming asset would be transferred to farmer together with all debt. An investigation was required to see if that could be done economically.

- Some off farm assets would be purchased for the parents by debt secured on the farm.

- Parents would retain off farm assets for place to live, security and partial income.

- Some farm assets would likely be retained by parent until death for security as well but are “earmarked” for the farmer.

- Off farm assets (with no debt) are to go to the non-farm child – structure to aid in the security of those assets until transfer was to be investigated.

- When taking into account unpaid wages to date and estimated future funding requirements for parents plus the current value of net assets earmarked for both children, inheritance was “reasonably equal” and deemed to be fair.

Post meeting

Everyone decided the succession meeting was a great success and everyone was happy.

The major concern, from all the family and the professionals involved in the meeting was that the farm may be unviable with the new debt loads following the past decade of poor agricultural profitability. The farmer was, however, willing to “give it a go” and was happy that there was certainty of succession and estate planning process.

The various family groups continued to have very good relationships and everyone “got on with life”. Everyone was happy to have Christmas together and conversations were “happy and relaxed” – a good measure of success.

Today- eight years post succession and estate plan- what went wrong?

- The farmers have a couple of tough years but complete a lot of farm development and productivity improvements.

- A number of years after the ‘succession meeting’ the parents and farming child investigate the transfer of farm land to the next generation and discover this is quite easy and without cost due to various government exemptions and role-overs, 80% of farm land is transferred to farming child.

- By the late 2000s they have debt under control and start to make modest profits.

- Farming child invests in off farm real-estate using farm assets as security.

- The neighbouring farm comes up for sale and the farming child buys it, stretching equity.

- Farm asset values rise dramatically in mid to late 2000s following land use change and rises in profitability of farms.

- Stock market crashes following GFC.

- There is a build-up of dissatisfaction from the non-farming child with the whole outcome.

The result of all this was that “words were spoken” at a family gathering; no more happy Christmases together; serious dispute.

Serious dispute

- The non-farming child discovers that the majority of the farm land has been transferred by the parents to his sibling and doesn’t believe that was part of the agreement. They are now concerned that the family asset is at risk if his sibling were to be divorced.

- By late 2000s the net value of the farming assets have increased significantly driven by the increase in asset value and the high level of gearing.

- Despite this, the farm is currently barely viable under the weight of debt, current commodity prices and some difficult seasons.

- The value of share market (part of the non-farm assets earmarked for non-farming child) falls significantly with the global financial crisis.

- The non-farming child questions the process following the original succession and estate planning meeting, the fairness of the outcome now and the security of their parents’ income and assets and the potential estate.

- This develops into a nasty emotional dispute between the siblings (and their spouses) with threats of legal action, etc and puts serious pressure on the parents who thought succession was completed and everyone was happy.

Increasing the likelihood of a successful succession process

There are a number of factors that are important to improve the likelihood of a successful succession process. These are:

- Separate the succession and estate plans.

- People matter most. Set the ground rules and guiding principles for decision making. Start with needs and objectives.

- Time frame is important (i.e. do it early, take your time – don’t barge through).

- Allow for a balance of flexibility and certainty.

- Ensure education about future implications.

- Go through and understand the “What ifs” – All the D words – death, divorce, disagreement and disability.

- Formal agreements are vital – deed of family arrangements.

- Succession is a process and a journey not a destination.

Succession versus estate transfer

- Succession is the transfer of control and ownership of the business (not the land assets). It needs to occur as one generation reduces their input into the business and the second generation seeks to move in their own direction.

- Estate transfer is the transfer of the major fixed assets. This can occur at any time and not necessarily at the same time as the transfer of the business.

Both are connected but are mutually exclusive and can happen at different times. Even where they are dealt with at the same time they should be considered separately.

Set the ground rules/approach to succession

First the parents need to establish what I call the ‘rules of the game’. In essence this is how decisions are going to be made. This can vary from the parents deciding right through, to the parents handing over the decision to the children with some guidelines. The important thing is that the ‘rules of the game’ are clear. I see too many situations where it is implied that this will be a group process and everyone will have a say in the decisions, only to have Dad or Mum veto that decision. If Mum and Dad are going to have a veto, state that up front.

People matter most – needs and fairness

Ultimately a succession process will only be successful if people are happy at the conclusion of the plan and into the future. Interestingly in the succession research, the number 1 objective (over 95% of stakeholders) from all generations was to maintain and enhance relationships and trust between all existing and new family members (Gamble, 2003).

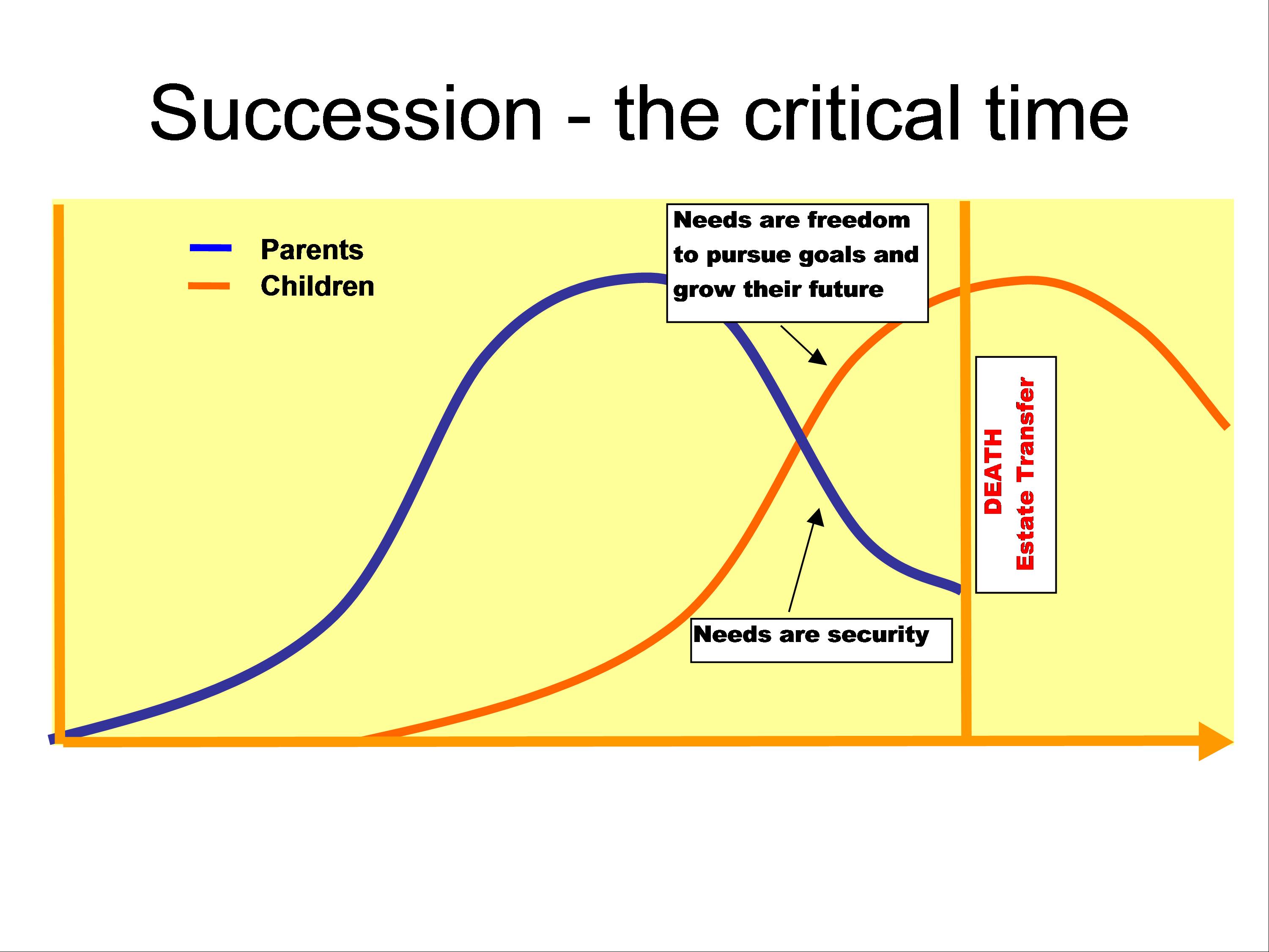

Exploration of needs often takes longer than most would expect and it is vitally important to get individual needs and objectives clear with all family members before moving on to exploring options for succession and finally looking at structures and agreements. The needs of the two generations will have some overlap but typically there are also differing needs that are actually conflicting i.e. Security for parents and independence and growth for the children as outlined in Figure 1. As the level of control is passed from one generation to the next (the cross over) this is the time when conflict is most likely between the generations if these conflicting needs are not discussed and resolved.

Figure 1. Process of succession.

Too often succession plans start with “what we are going to do?” and “what structures will we use?” before exploring the base needs and objectives of the individuals. People assume they know or find it too difficult to discuss.

Exploring needs and objectives leads to the development of guiding principles for succession decisions. These guiding principles can then be used progressively as a check to see if options and decisions are “on track”. A typical set of guiding principles maybe something like (without any detail):

- Family harmony;

- parents have a secure income at all times;

- a viable farm is maintained;

- security for farming siblings; and

- fair distribution of assets in any estate plan.

The detail of these guiding principles should be explored and defined in each family i.e. What does a viable farm look like? What does security look like? What is fair?

Ideally all guiding principles can be met; however, it is not always feasible, possible or practical for that to occur. In that regard, it is important for the family, and particularly the parents, to prioritise these guiding principles and say which ones are “not negotiable”. This will vary from family to family.

Different families will have varying processes or cultures about how this is developed. For example, some families will have everyone involved with equal input and other families will be directed by the parents with the parents seeking guidance and input from the children but ultimately say; that this is “my succession”. Neither way is right or wrong, it is a matter of developing the appropriate culture in the business and setting the “rules of the game” early from the outset of any succession process.

In the case study, the farming child had been thinking about succession for a long period of time, had received education on the subject and had clear objectives. The non-farming child came to the process at a much younger age and had not had the same opportunity to be clear on their needs and objectives. To give a greater chance of long term success the process should have occurred over a number of meetings with needs and objectives clearly defined, not just one meeting where the overall strategy was mapped out in one go.

Time frame is important (i.e. do it early, take your time and don't barge through

As described above the succession and estate plans have a greater chance of success if the planning process is started early and you take your time to get everyone to a similar level in the discussion during the planning process.

As an analogy, if someone needed to travel from Launceston to Melbourne there would be more choice in how to complete the task if they have a long lead-in time before needing to travel. If they needed to get there immediately (because of a crisis) then their transport choices are limited, the process will be expensive and stressful and there is a chance they won’t make it. Succession is exactly the same. The earlier it is started the more options there are available and it is more likely to reach a successful outcome. With plenty of time it is more likely that more or all of the guiding principles can be met i.e. time to build up the scale or viability of the farm or level of off farm assets for parental security.

Balance of flexibility and certainty; education on future implications and “what ifs

A succession agreement reached at a point of time will be a reflection of the present situation and what is expected to happen in the future. The next generation of farmers will seek certainty so they can plan their future, work on growing the business and taking control of their own destiny. This is a good thing and experience shows that the greater the certainty the more likely the business will continue to grow under the control of the new generation of manager(s). The case study is an example of this, where the young farmer had real incentive to make the farm profitable and expand for their own family’s future. Uncertainty breeds an environment of “who am I doing this for?” which can demotivate and cause the business to stagnate or decline. The flip side of this is that if the business does very well and expands, etc. the siblings not involved with the farming assets can feel that they have been hardly done by. Gearing can have a very big impact here. Often to get fairness the next generation of farmer(s) will be entitled to, or have transferred to them, the farm assets with a fair degree of debt. If the business is successful and the assets appreciate then the next result will be a much larger net worth for those children inline to receive a geared asset as opposed to a non-geared asset (see Table 1 for the type of result that occurred in the case study).

Table 1. Change of asset values over time.

|

|

Farm sibling 1 |

Non-farm sibling 2 |

|---|---|---|

|

Year 1 |

$4.0M assets - $1.5M debt and parental responsibly (est $0.5M) = $2.5M equity |

$2M assets 0 debt and no parental responsibility = $2M equity |

|

Future – Farm Assets double (plus buy new $2M farm with debt) Non-farm asset = lower growth |

$11M assets - $3.5M debt = $7.5M equity |

$3M assets – 0 debt = $3 M equity |

The reverse, however was also possible i.e. If the business is unsuccessful then the geared scenario will likely be worse off and could even lose equity or even go broke.

For the reasons above it is important to have a discussion about implications of what people agree to, education on risk reward, gearing and investment and that the future outcome in terms of assets value will be very different to what is agreed at this point in time. Some balance between certainty (allowing the next generation of farmer to get on with it) and flexibility (some assets left up in the air) can be helpful. Some families look at average asset values over a period of five years when looking at fairness of splitting the assets.

Key discussion and education points when assets are transferred

- Can the new asset controller sell and if so in what circumstances?

- Can the new asset controller gear for new farms or other assets?

- Gearing who takes the risk and reward? What if the net asset values are very different in the future?

- What if the famer goes broke?

- What if parents lose other assets earmarked for non-farmers and/or income?

- What if there is divorce with parents or child and spouse?

- What if children predecease parents or are disabled? Does the business and transferred asset revert to the parental family or is the spouse and/or children of the deceased sibling entitled to the business and assets?

- What if there are disagreements in the future? Define a process.

In the above case study none of these potential circumstances were discussed, so when ‘things’ happened, there were different perceptions about the fairness of the outcome.

Formal agreements

The main advantage of formal agreements is the process rather than the result. Formal agreements mean agreements are recorded in a clear and concise manner. It also means that the process gets concluded to a point in time. It gives the opportunity for individuals to have a “cooling off period” from any agreement reached in a discussion or meeting format and allows stakeholders to obtain individual advice.

ProAdvice consultants are asked to help in too many succession disputes where a succession process has taken place previously and past agreements have either not been documented or documented in minutes that become ambiguous through the passage of time.

The case study is an example of where a deed of family arrangement would have helped to avoid future dispute.

A succession and estate planning model

Figure 2 is an outline of a successful succession and estate transfer process. This process is based on a process initially developed by John Lord and refined by me over time. This process takes into account all the “key success factors” described in the previous section. The red line is a barrier that must not be passed until the family’s needs and objectives, guiding principles and approach to decision making are clear and understood by all.

| 1. Define the approach or ground rules to decision making 2. Define & discuss individual objectives/needs and group these 3. Determine the guiding principles for business succession and asset transfers |

| 4. Explore all options & possible strategies 5. Agree on the best option and strategic plan required to get there 6. Discuss "What ifs" & implications of agreements and refine where necessary 7. Complete structures and agreements 8. Determine review time-frames |

Figure 2. Succession and estate planning process.

Useful resources and references

Resources

A Guide to Succession – Sustaining families and farms – GRDC publication by Judy Wilkinson and Lyn Sykes – available at GRDC .com.au

GRDC fact sheet – succession planning September, 2010.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics data – ABS website

Barclay, E, Farm Succession and Inheritance: An International Comparison. Institute of Rural Futures – Derived from RIRDC funded research (2007).

Barclay E., Foskey R., and Reeve I. 2007. Farm Succession and Inheritance – Comparing Australian and International Trends. RIRDC Publication # 07/066, Rural Industries Research & Development Corporation.

Farm Succession planning – Rural Law online Forum - Dec 2005 report

Crosby, E 1998, ‘Succession and inheritance on Australian family farms’, Paper presented at

Changing Families, Challenging Futures, 6th Australian Institute for Family Studies

Conference, Melbourne, 25-27 November 1998

Gamble D., Blunden S., and Ramsay G. 2003. Sustaining the family farm system: An integrated approach to linking the social, business and environmental aspects. 1st Australian Farming Systems Conference.

Gamble D., Blunden S., Kuhn L., Voyce M., and Loftus J. 1995. “Transfer of the Family Farm Business in a Changing Rural Community”, RIRDC Report No 95/8, Rural Industries Research & Development Corporation, Canberra.

Sheng Y., Zhao S. and Nossal K. 2011. Productivity and Farm size in Australian agriculture: reinvestigating the returns to scale. AARES

Contact details

Andrew Beattie

ProAdvice Pty Ltd