Integrated management of crown rot in a chickpea – wheat sequence

Integrated management of crown rot in a chickpea – wheat sequence

Author: Andrew Verrell, NSW Department of Primary Industries | Date: 23 Feb 2016

Take home message

- Sow chickpea crops between standing wheat rows

- Sow the following wheat crop directly over the row of the previous year chickpea crop

- Keep wheat stubble intact and do not spread it across the surface

Introduction

Crown rot, caused by the stubble-borne fungus Fusarium pseudograminearum (Fp), remains a major limitation to winter cereal production across the northern grains region of Australia. Crop sequencing with non-host crops has proven to be one of the best means of reducing the impact of crown rot (CR) infection (by 3.4-41.3%) and increasing wheat yield (by 0.24-0.89 t/ha) compared to a cereal-wheat sequence (Kirkegaard et al. 2004, Verrell et al. 2005). While inter-row sowing has been shown to reduce the impact of CR and increase yield, by up to 9%, in a wheat-wheat sequence (Verrell et al 2009). Verrell et al. (2014) showed that using mustard-wheat and chickpea-wheat crop sequencing resulted in a 40-44% increase in wheat yield over a continuous wheat system under zero-tillage and adding inter-row sowing increased wheat yield by a further 11-16% depending on the row placement sequences.

Chickpea are the most prevalent break crop grown in sequence with wheat in the northern NSW region. Chickpea crops are reliant on the use of post-sow pre-emergent residual herbicides (Group C and H) for broadleaf weed control. A common commercial practice is to level the seeding furrow after sowing, usually with Kelly chains, to avoid the risk of herbicide residue concentrating in the furrows and causing damage. The consequence of leveling the seed furrow to avoid possible herbicide damage is that any standing wheat residue, under a zero-tillage system, is shattered and spread across the entire soil surface. If this wheat residue is infected with Fp then CR inoculum is no longer confined to the standing wheat rows.

There was a need to examine whether integrating row placement, stubble management, chickpea row spacing and ground engaging tool would affect the incidence of Fp and grain yield in wheat in a chickpea– wheat sequence grown under a zero-tillage system.

What did we do?

A three year crop sequence experiment (wheat-chickpea-wheat) was established at Tamworth in 2012 to examine the effect of ground engaging tool, chickpea row spacing, row placement and wheat residue management on the incidence of Fp and grain yield of a wheat crop.

In 2012, durum wheat (EGA Bellaroi) was sown into a cultivated paddock using a Trimble® RTK auto-steer system fitted to a New Holland TL80A tractor with narrow row crop tyres. The crop was sown with a disc seeder on 40 cm row spacing and bulk harvested with the residue cut at a uniform height of 24 cm.

In 2013, chickpea (cv. PBA HatTrick) was sown at 80 kg/ha and treatments consisted of: main-plot was row placement (between or on 2012 wheat rows); sub-plot was stubble management (standing or slashed and spread); sub-sub plot was row spacing (narrow 40 cm or wide 80 cm); and sub-sub-sub plots were ground engaging tool (Barton® single disc opener or Janke® coulter-tyne-press wheel parallelogram). The stubble management treatments was applied after the plots were sown.

In 2014, wheat (cv. EGA Gregory) was sown over the chickpea plots and treatments consisted of: sub-sub plots as row placement (between or on 2012 wheat rows); and sub-sub-sub plots were ground engaging tool (Barton single disc opener or Janke coulter-tyne-press wheel parallelogram).

What did we find?

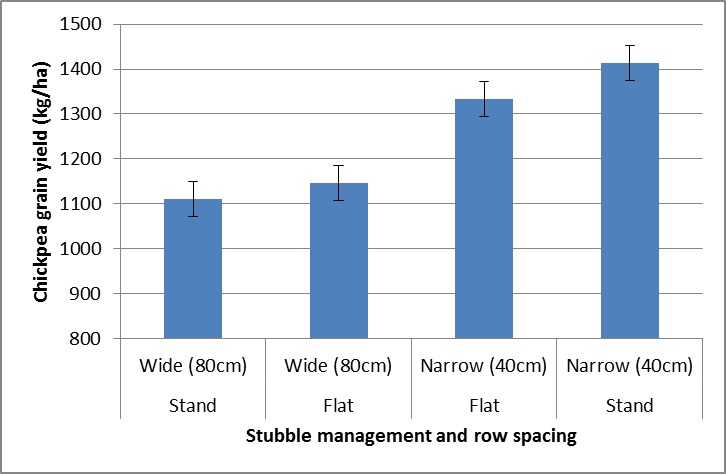

Chickpea grain yield increased when sown with a disc opener (by 6%), on narrow rows (by 22%) and sown between the 2012 wheat rows (by 7%) but stubble management did not have a main effect on chickpea yield. However, stubble management had a significant interaction with row spacing when sowing chickpeas on narrow rows (40 cm) into standing residue out-yielded narrow rows (where the residue had been slashed (by 6%) (see Figure 1)). There was no significant yield effects with chickpeas sown on wide rows (80 cm) whether the wheat residue was left standing or slashed.

Figure 1. Effect of row spacing and wheat stubble management on chickpea grain yield (kg/ha)

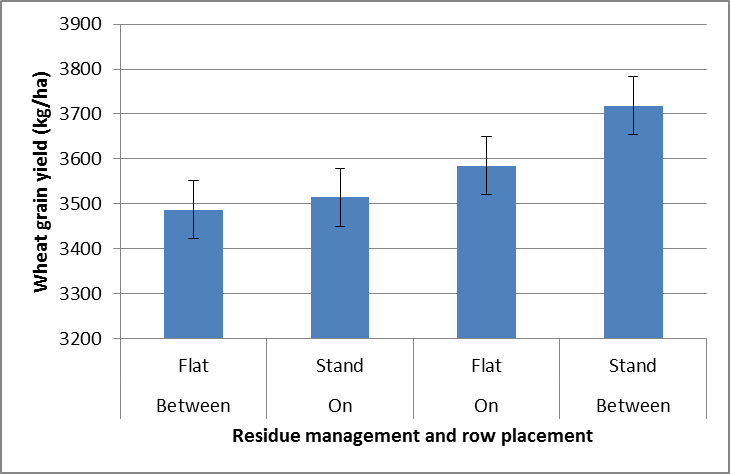

In the 2014 wheat crop, sowing with a coulter-tyne-press wheel out-yielded the disc opener (by 6.3%). Row placement of the wheat (relative to the 2012 wheat crop) had a significant interaction with the stubble treatment in the 2013 chickpea crop. Where wheat was sown into the space between the old wheat rows (2012) and the stubble was left standing in the 2013 chickpea crop it resulted in the highest grain yield (3718 kg/ha) (see Fig. 2). This was significantly higher than the other row x stubble combinations; on-row x flat, on-row x standing and between-row x flat which yielded, 3585, 3515 and 3487 kg/ha, respectively, which were not significantly different from one another.

The incidence of Fp at harvest, as main effects, was lower where chickpeas had been sown between wheat rows (6.6%) compared to on the row (10.0%) and lower when stubble was left standing (6.4%) compared to spreading (9.9%). The type of ground engaging tool, row spacing in the previous chickpea crop or row placement of the 2014 wheat crop had no significant main effect on the incidence of Fp at harvest. For the narrow row (40 cm) chickpea system; sowing on the old wheat row led to a significant increase in the incidence of Fp at harvest in the following wheat crop (11.8%) compared to sowing between the old wheat rows (5.8%).

Figure 2. Effect of row placement (relative to the 2012 wheat crop) and stubble management in the 2013 chickpea crop on grain yield (kg/ha) in the 2014 wheat crop

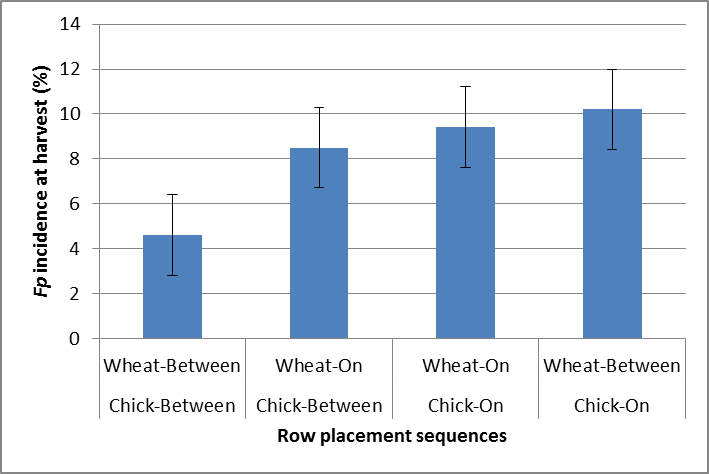

Under the wide row (80 cm) chickpea system; row placement had no effect on the incidence of Fp (mean 7.5%). Sowing the 2013 chickpea crop between standing wheat rows and the following wheat crop directly over the previous chickpea row and between the old wheat rows resulted in the lowest incidence of Fp (4.6%) (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3. The interaction of chickpea row placement (2013) and wheat row placement (2014) on the incidence of Fp in wheat

Other row placement combinations; chickpea between wheat rows x wheat on-rows, chickpea on wheat rows x wheat on-rows, and chickpea on-rows x wheat between wheat rows resulted in Fp levels of 8.5, 9.4 and 10.2%, respectively.

Conclusion

At Tamworth in 2013, sowing chickpea on narrow rows (40 cm) realised a 22% yield advantage over wide rows (80 cm). Also sowing chickpeas between standing wheat rows resulted in a higher yield (by 6%) compared to sowing the crop then slashing the wheat stubble and spreading it across the surface. Growing chickpeas between standing wheat stubble has been shown to provide a yield advantage in previous studies largely by reducing the incidence of aphid transmitted viruses (Verrell and Moore 2015).

The highest wheat yield (3718 kg/ha) came from sowing the wheat into the inter row space of the old wheat crop (2 years old) and keeping the stubble standing. Using a tyne also resulted in a yield advantage over a disc opener. When stubble was left standing the incidence of Fp was lower (6.4%) compared to spreading stubble across the surface (9.9%). Sowing the 2013 chickpea crop between standing wheat rows and the following wheat crop directly over the previous chickpea row and between the old wheat rows resulted in the lowest incidence of Fp (4.6%). Any stubble management practice which spreads residues into the inter row space is likely to undo row placement benefits associated with reducing the incidence of crown rot infection, as Fp inoculum is no longer confined to the standing wheat rows. The perceived crop safety benefits of leveling the seeding furrow after applying post-sow pre-emergent residual herbicides (Group C and H) in chickpeas needs to be balanced against potential impacts on chickpea yield and increased incidence of crown rot infection in the following winter cereal crop.

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of project DAN00171 is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support. Thanks to Michael Nowland and Paul Nash (NSW DPI) for their assistance in the trial program. Fp levels were kindly determined through laboratory plating by the NSW DPI Cereal Pathology Group based at Tamworth.

References

Verrell, A.G., Simpfendorfer S., Nash P. and Moore K. (2009) Can inter-row sowing be used in continuous wheat systems to control crown rot and increase yield? 13th Annual Symposium on Precision Agriculture in Australasia (2009), UNE, Armidale.

Verrell, A.G., Simpfendorfer S., Nash P. and Moore K. (2005) Crop rotation and its effect on crown rot, common root rot, soil water extraction and water use efficiency in wheat. Proceedings 2005 GRDC Grains Research Update, Goondiwindi.

Verrell A (2014) Managing crown rot through crop sequencing and row placement. GRDC.

Verrell A and Moore KJ (2015). Managing viral diseases in chickpeas through agronomic practices Australian Agronomy Conference, Hobart.

Contact details

Dr Andrew Verrell

NSW Department Primary Industries

Ph: 0429 422 150

Email: andrew.verrell@dpi.nsw.gov.au

Reviewed by

Dr Steven Simpfendorfer

Varieties displaying this symbol beside them are protected under the Plant Breeders Rights Act 1994

GRDC Project Code: DAN00171,