Aphids and other green profit suckers

Aphids and other green profit suckers

Author: Melina Miles, Adam Quade, Richard Lloyd and Paul Grundy, Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries | Date: 27 Feb 2017

Take home message

- Russian wheat aphid has not yet been detected north of Rankin Springs in the Riverina district of NSW. Vigilance is required to ensure early detection of any outbreaks in the northern region this winter.

- Winter cereal aphids can be managed successfully with nominal thresholds and an understanding of their damage potential.

- Green mirids do cause spotting on faba bean seed, and impact on seed size/yield. Both adults and late instar nymphs are damaging and warrant control in faba bean crops. No threshold has been determined as yet.

RWA as a pest in the northern grains region

RWA is considered a high priority pest by the grains industry because of its potential to cause significant yield losses in wheat and barley if not well managed. Triticale and rye are also susceptible to crop loss, but oats are considered relatively tolerant.

The RWA is more damaging to cereals than the aphid species we already have in Australia. We don’t yet know how susceptible Australian varieties are to RWA. GRDC is investing in the development of resistant cultivars for Australia. In the meantime, international experience with RWA has been that in seasons following outbreaks, yield losses are generally lower as growers are better equipped to detect and manage infestations, and natural enemies establish and contribute to the suppression of populations. In South Australia and Victoria in 2016, infested crops that were treated to control RWA, recovered to grow and yield normally.

It is inevitable that RWA will establish in the northern grains region, but we don’t know when we will start to see it in crops. Given how widely distributed RWA is in SA and Victoria, it seems likely that RWA has been in Australia for some time prior to the 2016 outbreak. An outbreak is most likely in the event of favourable conditions for RWA populations to both over summer, build up in winter and move into early crops in autumn. The environmental conditions that favoured the outbreak in the southern region were a wet summer (summer hosts), a warm autumn and early sowing of winter cereals (favour rapid population growth and movement from weed hosts to crops). In addition to crop hosts, non-crop and pasture grass species in the genera Poa, Bromus, Hordeum, Lolium, and Phalaris may also host RWA. It remains to be seen whether RWA survive over-summer, on grass hosts or crops (e.g. sorghum, maize, millet, canary) in the cropping landscape.

In the 2017 season, it is important that crops are monitored more frequently than they might usually be to ensure early detection of RWA, should it occur.

Sample for RWA in the same way you would sample for other cereal aphids. Concentrate on the field margins and in areas of the paddock that are stressed (dry, wet, root disease). Look for both symptoms (see description below) and the presence of aphids.

The following thresholds are recommended:

Emergence to tillering - 20 RWA per plant

Tillering onwards (Z30-59) – 10 aphids per tiller.

If control of RWA is warranted, an Emergency Use Permit (APVMA PER82792) is in place for chlorpyrifos and pirimicarb and is valid until June 2018. Pirimicarb will kill aphids, but not the beneficial insects in the crop. If possible, use this option first to preserve beneficials which may then suppress further outbreaks.

RWA identification and distinguishing it from other aphid species

Table 1. Characteristics of wingless aphids (***=key feature)

|

Russian wheat aphid |

Rose grain aphid |

|

|

|

Oat aphid |

Corn aphid |

|

|

Photo: R. Daniels |

|

Resources for identification of aphids GRDC Crop Aphids Backpocket Guide I Spy – Insects of Southern Australian Broadacre Farming Systems Identification Manual |

|

***key features

Leaf symptoms caused by RWA infestations

RWA induce striking symptoms in wheat and barley, unlike the oat and corn aphid which produce no obvious symptoms. Within a week or so of being infested with RWA, plants will start to exhibit symptoms. Plant damage is in response to direct aphid feeding, so only the leaves and/or tillers infested show symptoms.

- White streaking of the leaves. Some varieties show reddening.

Figure 1. White streaking of the leaves. Some varieties show reddening.

- Rolled leaves. RWA colonies shelter inside the rolled leaves.

Figure 2. Rolled leaves. RWA colonies shelter inside the rolled leaves.

- Infestation of plants up to head emergence can result in rolling of the flag leaf, resulting in the head being trapped in the boot.

Figure 3. Rolling of the flag leaf resulting in the head being trapped in the boot

Some of these symptoms are similar to those caused by wheat streak mosaic virus (WSMV) and phenoxy damage in cereals –close examination of symptomatic plants to determine the presence of RWA is recommended.

Resources

Plant Health Australia Biosecurity Portal (RWA distribution map, factsheets)

Cereal aphid thresholds (oat, corn and rose grain aphids)

Field trials to determine the impact that aphids are having on winter cereals has been attempted over the past 10 years, but has proven extremely difficult to achieve.

In 2008-09, the Northern Grower Alliance (NGA) showed that using the nominal threshold of 10 aphids/tiller provided protection from yield loss in 61% of the trials they conducted. They also showed that in some instances, the use of seed dressings or the application of foliar treatments provides significant economic benefit (NGA 2010).

DAF entomologists have conducted around 10 field and glasshouse trials over the past 7 years, and whilst not being able to confirm an economic threshold, this work and that of the NGA, has been useful in developing a better understanding of aphids in winter cereals, and a reasonable management approach for cereal aphids. It is this approach that I will outline here.

Aphids can cause yield loss

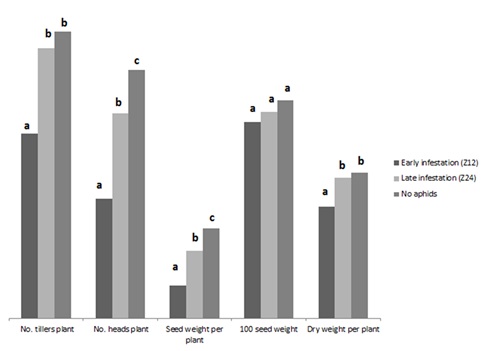

In a glasshouse trial, we found that early, sustained aphid infestations could affect a number of growth and yield parameters in barley (Figure 4). Yield potential (number of tillers, heads and dry weight) were affected, and consequently yield. Earlier infestation (seedling vs tillering) resulted in greater impact.

Figure 4. Relative impact of early sustained and later infestation of Rhopalosiphum padi on barley in the glasshouse (20-200 per tiller). Means followed by the same letter are not significantly different from each other.

If aphids can cause yield loss, why is it so hard to get a threshold?

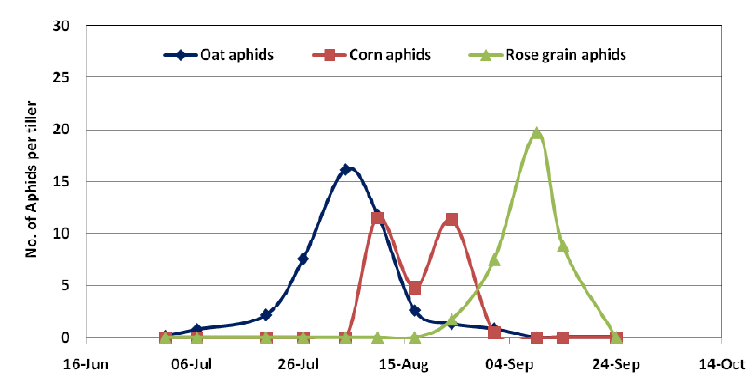

Aphid infestations are highly variable between crops and seasons. Typically, a crop in the field will not have sustained high pressure from seedling to maturity. Weather, crop conditions and natural enemies all play a role in influencing aphid numbers. The other variable is the species of aphid. We don’t know whether the different species are all equally damaging. In 2008-09, the NGA collected data on which species were present in barley (Figure 5). What this shows is that the species are not all present in the crop at the same time or at the same densities.

Changing aphid species and density through late winter and spring is common in cereal crops across the northern region. It is this changing pest pressure on the crop that we think allows for crop compensation and minimises the in-field losses caused by aphids. It also makes it incredibly difficult to get replicated, consistent infestations in trials.

Figure 5.Population dynamics of 3 species of cereal aphid on untreated Fitzroy barley, Moree 2009. NGA.

A management strategy to minimise crop loss from aphids in winter cereals

Across the replicated field trials DAF has conducted, there is a trend towards greater impacts on yield with earlier infestations where conditions are conducive to persistence of aphids. The damage potential of aphids in cereals seems to be based on the relationship between crop stage at infestation, density, and duration of infestation.

Aphid populations often decline naturally as a result of changing crop suitability, weather and the activity of natural enemies. However, anecdotal observation suggests that aphids may be persisting longer in the newer varieties of wheat and barley. The old rules of thumb (i) that corn aphid will disappear as heads emerge, and (ii) oat aphid populations decline when the crop becomes reproductive, (iii) aphids do not colonise heads during grain fill do not seem to be holding as consistently as they did. Perhaps the genetics that make cereals drought tolerant are making them more suitable for aphids? These changes may be something that the rose grain aphid is better able to exploit.

Seed treatment

Seed treatment is an option for districts where aphid pressure is high in most seasons. The widespread use of neonicotinoid seed dressings does pose some risks to the build-up of natural enemies (no aphids early = nothing for them to eat) and potentially insecticide resistance.

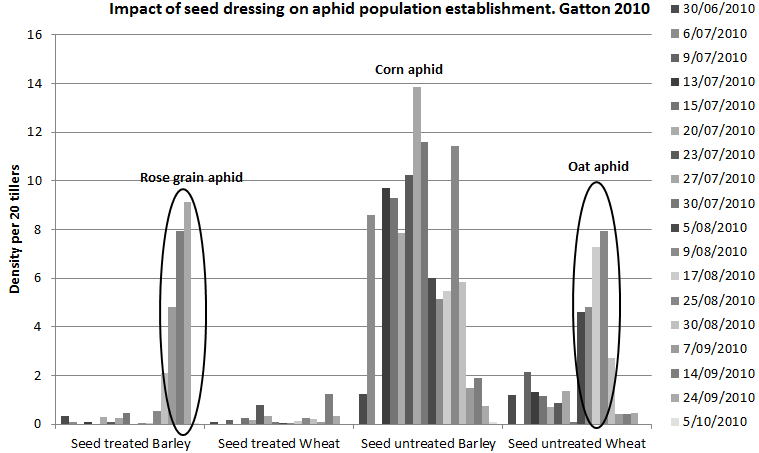

The other consideration is that by spring (August-September), the effectiveness of the seed treatment may have declined to the point where infestation and rapid build-up of aphids is possible. Warm autumns and mild springs are the most likely conditions for aphid build up in cereals. Figure 6 shows an example of how aphid populations differ between seed treated and untreated crops. The key point is that the use of seed dressings does not prevent all potential aphid infestation for the duration of the crop. Crop monitoring in spring is still required.

Figure 6. Pattern of aphid build up in wheat and barley, with and without seed treatment.

Crops planted on 10 June.

Seedling and tillering crops

Aphids have the potential to continue to build in number and exert stress on the crop, reducing yield potential. Treating a large and growing aphid population in a tillering crop is probably the one time when you have the opportunity to reduce impact on yield. The earlier a crop is treated for aphids, the more time there is for survivors, or new immigrants, to establish in the crop. Selecting a product that minimises disruption to natural enemies (e.g. pirimicarb, sulfoxaflor) is particularly important to minimise the possibility of a subsequent outbreak.

Booting to grainfill

If the crop has been below threshold up until this point, and growth not constrained by adverse conditions, the impact on yield potential will have been low. The potential impact of late infestations of aphids, particularly from grain-fill on is low, particularly if they are colonising the lower leaves. In the northern hemisphere, late infestations low in the canopy can result in lower N (protein) rather than reduced yields.

Inspect the crop more than once over a period of 1-3 weeks to determine whether the population is persisting or infesting the flag, flag-1 or head.

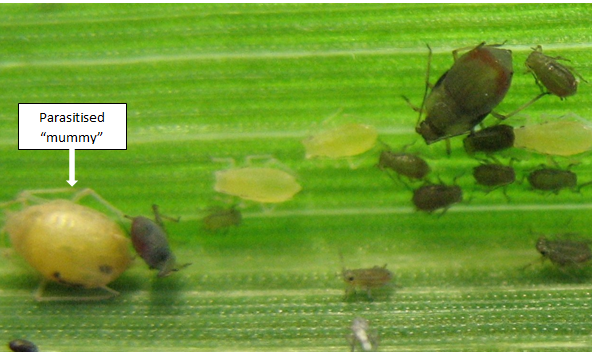

Be aware of the activity of natural enemies. Once you start to see aphid mummies (evidence of parasitism by wasps), decline of aphid populations is typically rapid (Figure 7). Other common natural enemies include ladybeetles, and hover fly larvae.

Figure 7. A parasitised rose grain aphid (far left) along with oat aphid adult (dark green, reddish band), oat and rose grain nymphs.

Confirmation of green mirid damage potential in faba beans

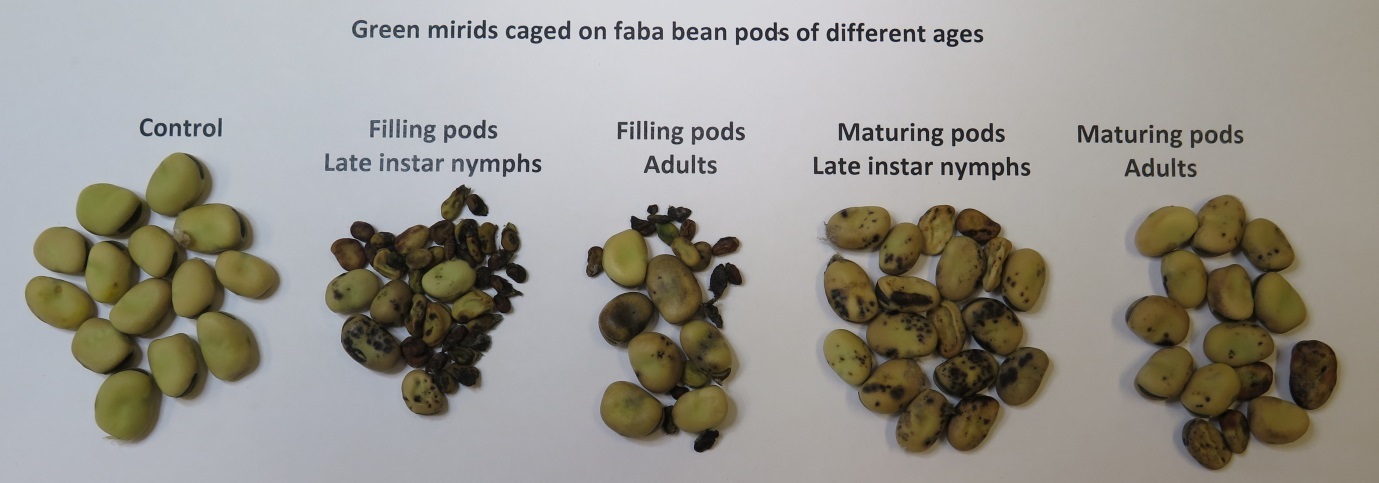

A replicated trial that caged mirid adults or nymphs on developing and maturing pods was conducted in 2015. The purpose of the trial was to establish conclusively whether mirid feeding caused spotting on the seed, and whether mirids warranted further research as a pest of faba beans.

Pods at two development stages were included in the trial, 1) fully filled, but still green and 2) immature, seed approximately 30% filled. Either 2 adult mirids, or 2 late instar nymphs were confined on a pod for 10 days, and there were control pods on which there were no mirids. At the end of the 10 days the mirids were removed from the ‘cages’ and the cages replaced to protect the pods from being damaged by any other insect or weather. Cages remained on the pods until the pods were mature and dried down (harvestable). During this time cages were checked, and treated where necessary for small nymphs that hatched from eggs laid by the mirids in the trial.

Figure 8. Effect of green mirids caged on faba bean pods of different ages

As shown in the figure above, mirids did consistently cause spotting on the seed coat. Adult and late instar mirids caused similar damage. When filling pods were exposed to mirids, a significant proportion of seed did not develop. This trial result clearly demonstrates the damage potential of mirids in faba beans, both in terms of quality (spotting) and yields (small seed).

This trial was not designed to address the question of threshold. We cannot extrapolate from these data to estimate how many mirids will cause significant seed spotting or screenings. These are areas of research that will be addressed as opportunities arise. In 2016, mirid densities were very low in late winter – early spring; consequently further work on thresholds was not possible in that season, but it is a priority for 2017.

References

Northern Grower Alliance. 2010. GRDC Update paper. Goondiwindi. Aphids in winter cereals.

http://www.nga.org.au/results-and-publications/browse/13/aphids-in-winter-cereals

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support.

Numerous agronomists and consultants have assisted with the location of field sites, prompted research, and discussed issues and solutions. We are grateful for their ongoing support and encouragement and their commitment to implementing the outcomes of our research with their clients.

Contact details

Melina Miles

Queensland Department of Agriculture and Forestry

203 Tor St, Toowoomba. Qld 4350

Ph: 0407 113 306

Email: melina.miles@daf.qld.gov.au

GRDC Project Code: DAQ00196,