Paddock Practices: Dry sowing and pre-emergent herbicides

Paddock Practices: Dry sowing and pre-emergent herbicides

Author: Mark Congreve | Date: 21 Mar 2022

Obtaining consistent performance from a pre-emergent herbicide used with dry sowing is often difficult, as it is impossible to predict the timing and magnitude of the opening rainfall event.

General principles include:

- Do not dry sow paddocks with high weed seedbanks – delay sowing until after an effective knockdown strategy is implemented.

- Ensure correct depth of seed placement. This can be especially difficult in dry conditions.

- For herbicides sensitive to environmental losses, incorporate soon after application.

- Low disturbance disc seeders are not recommended for use with several herbicides, as they do not provide the required spatial separation of crop seed and herbicide, which is often essential with dry sowing.

- A herbicide with a low level of mobility (low water solubility and higher level of soil binding) may often be of a lower risk for crop damage and may remain in closer proximity to the weed seeds – thus assisting weed control. However these herbicides may give poor control if rainfall after the break is low or patchy, or where the paddock has been previously cultivated and weeds seeds germinate from depth.

Having a crop germinate as close as possible to the targeted time for that variety often helps to optimise yield potential. For larger operations, the need to sow big areas in a short space of time to meet the correct germination window poses logistical challenges.

As a result, sowing some paddocks dry before the expected break to the season is a tactic used by many growers to spread the planting operation and address these issues.

When the season does break, weeds typically emerge with, or sometimes ahead of the crop. Therefore it is important to have an effective pre-emergent herbicide in place to manage this first weed flush and allow the crop to establish with as little weed competition as possible.

There are several important points to consider when using pre-emergent herbicides and dry sowing.

Know your weed seed bank and where the weed seeds are

It may sound obvious, but users need to know what weed species are likely to emerge, so an effective herbicide can be chosen.

The size of the expected seed bank is also a very important consideration, as there is no opportunity for a pre-seeding knockdown herbicide when dry sowing. A large weed germination emerging with the crop will place extreme pressure on any pre-emergent herbicide. No pre-emergent should be expected to achieve 100% control, especially when applied dry. So even the best performing pre-emergent herbicides can still look ‘dirty’ after the season break if the starting population was several hundred weed seeds per metre. Therefore, only select paddocks for dry sowing that are known to have low weed seedbanks and leave sowing of ‘higher weed pressure’ paddocks until after a robust knockdown program can be implemented on the initial flush after the break.

The presence of high seed dormancy is likely to reduce effectiveness of pre-sowing weed control. High dormancy populations are less responsive to delayed sowing and knockdown herbicides because of slower weed establishment from the seedbank. These later emerging weeds can more aggressively compete with late sown crops as their vigour slows down in the cooler months and significantly impact yields. Improved familiarity with the dormancy behaviour of the weeds in different paddocks on the same farm will enable better targeting of weed populations with different management tactics.

Where are the weed seeds? In a long term zero-till paddock, most of the weed seeds should be close to the soil surface. In this situation, a low-mobile herbicide that will stay relatively shallow in the soil profile is likely to be preferred. However, if the paddock has recently been cultivated, then some of the weed seedbank will be deeper in the profile and therefore a more mobile herbicide may be needed to reach these deeper germinating weeds.

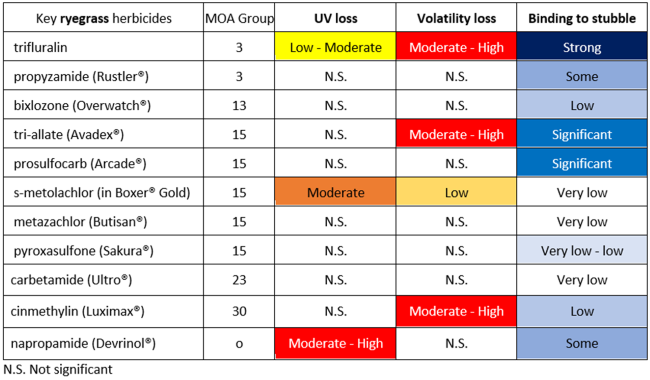

Herbicide loss to the environment

Some herbicides can be broken down by UV light or lost to volatilisation if left exposed to the environment. For these herbicides, the rate of loss generally increases with warmer temperatures and higher levels of sunlight – which often occurs with dry sown paddocks that are generally planted early.

If the herbicide being used is subject to these losses, then it will be important to ensure that it is correctly incorporated soon after application. A common ‘mistake’ that can occur, especially on very large seeding operations which tend to utilise dry sowing for logistical reasons, is that the speed of pre-emergent application is often significantly faster than the speed of sowing. So therefore the sprayer gets further and further ahead of the planter, and hence time to incorporation gets progressively longer. Ideally, for a volatile herbicide such as trifluralin, do not spray more than what can be sown within the following 4-6 hours.

Some herbicides will also bind to stubble.

Trifluralin binds extremely tightly to organic matter. Once it has dried on stubble it will effectively be impossible to remove with subsequent rainfall. The result is that less herbicide reaches the soil when used in a high stubble situation.

For other herbicides, the relative strength of binding provides an indication of the rainfall volume/intensity that will be required to move herbicide off the stubble on onto the soil.

Seeder type and set-up

A well set-up knife point and press wheel seeding system balances row spacing, speed of travel and soil characteristics, to remove herbicide treated soil from above the seeding trench and throw it into the inter row area to cover it, but without soil throw into adjoining seed trenches. Such a setup will generally reduce volatility and UV losses, while the mechanical incorporation from this process will also commence some soil binding (providing there is some soil moisture). Additionally, this system will move the majority of the herbicide away from the seeding row, which provides an increased level of crop safety.

In low rainfall environments it may be tempting to set up the tyned seeder to leave a distinct planting furrow to capture and concentrate any small rainfall events directly over the seed row in order to assist crop germination. Be aware that this practice may also concentrate residual herbicide directly over the seed and lead to crop damage.

A low disturbance disc seeder provides minimal soil throw and incorporation, leaving surface applied herbicides more exposed to the environment. For some herbicides, this may result in considerable environmental loss. Additionally, with many disc seeders, the seed slot may be left open. This may result in herbicide easily and rapidly moving into the planting slot following the first rainfall, which can often result in excessive crop injury.

Generally low disturbance disc seeders are not recommended for dry sowing with pre-emergent herbicides, and especially not with volatile herbicides which are subject to significant losses if not adequately incorporated.

In dry soils it is often difficult to maintain expected planting depth, especially in paddocks with variable soil types. While this can also occur with tyned planters, it is typically of more concern with disc systems. Vertical separation of the crop seed from the pre-emergent herbicide is extremely important when dry sowing. Sowing too shallow places the crop seedling closer to the herbicide and thus at potentially greater risk of damage.

Herbicide degradation after incorporation

Typically pre-emergent herbicides will be incorporated when dry sowing. If sowing is ‘early’ then the soil may still be warm.

All pre-emergent herbicides are degraded by soil microbes. The primary requirements for soil microbial activity are moisture and temperature.

- If the zone where the herbicide has been incorporated is totally dry, then there is unlikely to be any significant degradation occurring, until the opening rainfall.

- However, where there is some moisture in the soil at application, or there are small rainfall events that are not enough to initiate crop germination, then there is risk of some microbial herbicide degradation occurring prior to the true break. This will be more significant if sowing early when the soil temperature is still warm.

Where inversion tillage has occured, the subsoil at a depth of 20-30 cm is bought to the surface, replacing the top soil which is then placed at depth. Soil brought to the surface may have very different properties to the previous soil surface e.g. differences in pH and/or soil texture. It is therefore possible that this ‘new’ soil surface may behave very differently to the soil prior to the inversion tillage event. Depending upon the individual situation, it may be possible that more herbicide is freely available in the ‘new’ soil surface due to less organic matter and less microbial degradation, and hence greater risk of crop injury occurring. It is also possible that more herbicide binding occurs e.g. where clay is brought to the surface and sand placed at depth.

It is impossible to calculate how much herbicide may have degraded if the season break is delayed longer than planned, as there are many different factors involved and their impact will be different in every situation. Therefore it is not possible to accurately predict a rate to ‘top up’ the herbicide if emergence has been delayed. It is unlikely that the pre-emergent herbicide applied when dry sowing should completely ‘fail’ due to a delayed break, assuming it was adequately incorporated at application. However, the length of residual control may be reduced should there have been excessive losses prior to the break of season.

Where users are concerned that the expected length of residual may have been compromised, an early post emergent (EPE) of a registered pre-emergent should be considered.

What happens when the season breaks?

If the herbicide has not been incorporated (e.g. a low disturbance disc system) then opening rainfall will be required to wash the herbicide into the soil. Even when using an incorporation by sowing (IBS) system using knife points and press wheels, there will still be some herbicide remaining on the soil surface, or on stubble, which will be washed into the soil following rainfall (with the exception of products such as trifluralin which bind very strongly to stubble). The amount and intensity of rainfall along with herbicide properties of water solubility and how strongly they bind to organic matter and soil, will influence the degree to which this incorporation occurs with the first rainfall.

When starting with a dry soil, the first rainfall is likely to move rapidly down the profile, especially in sandy soils that have much larger air pores. Herbicide moving with this initial rainfall will move further than applications where the same herbicide was applied to a ‘full profile’ at application, where subsequent rainfall will not penetrate as far. This occurs with all herbicides; however individual herbicide differences also need to be understood.

The ability of a herbicide to wash off stubble and how far it will move with and after the initial rainfall, depends on both the herbicide solubility and its propensity to bind to soil and organic matter. Both are important.

The table below groups herbicides of roughly similar mobility. However, as many biological processes are involved, this is a guide only, with individual situations sometimes making a herbicide either more or less mobile than suggested.

Mobility / Ability to wash off stubble | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

Almost immobile. Unlikely to wash off stubble. Needs mechanical soil movement to shift location in the soil. | trifluralin | pendimethalin |

Relatively tight binding. Can move into soil providing enough rainfall volume and intensity. Well suited to IBS systems. | prosulfocarb | tri-allate |

Low mobility. Moderate to high rainfall required to move off stubble. Usually stays relatively close to the soil surface, even under higher rainfall situations. But can still move, especially in very sandy / low CEC soils. | diflufenican diuron flumioxazin | napropamide propyzamide trifludimoxazin |

Some mobility. Relatively easy to wash off stubble. Normally adequate crop safety is achieved, provided planting depth is maintained (usually >3cm for cereals). Sometimes can result in crop damage if initial rainfall event is heavy, especially when dry sowing on sandy soils. | atrazine bixlozone cinmethylin | pyroxasulfone simazine terbuthylazine |

Mobile. Easy to wash off stubble & get into soil. Difficult to keep away from the crop seed, especially in high soil moisture situations. | Group 2(B) Group 4(I) carbetamide fomesafen mesotrione | metazachlor metribuzin s-metolachlor saflufenacil |

‘Mobile’ herbicides will easily move into the soil following rainfall. Once in the soil, most of the herbicide will want to primarily remain in the soil moisture phase, with only a small amount of herbicide being bound to soil or organic matter. Highly mobile herbicides will move with water both horizontally and vertically in the soil moisture. Even if sowing with a knife point and press wheel system and the herbicide is moved into the interrow at application, these herbicides are likely to move back into the planting furrow following significant rainfall. When used in dry sowing, and especially in sandy soils, these mobile herbicides can move a long distance following rainfall (i.e. to the depth of the wetting front), and can often lead to crop damage unless the crop has an adequate level of tolerance to that herbicide.

Less mobile herbicides either have significantly lower solubility and/or much tighter binding to soil and organic matter, and hence do not move as extensively following the initial rainfall. Generally, if these lower mobility herbicides are applied by a correctly set up knife point system, the majority of the herbicide will be moved into the interrow, and will be less likely to move back into the planting furrow.

Note – herbicide binding is a chemical reaction that takes some time (days) to occur and typically requires some level of soil moisture for most herbicides. This means that if the herbicide was not incorporated or was incorporated during application but there was not enough soil moisture for binding to reach an equilibrium, then there may be a significant proportion of herbicide unbound at the time of the break. If the opening rainfall event is large, then even relatively immobile herbicides may sometimes move further than expected.

No pre-emergent herbicide binds completely to soil – if it did then it would be unavailable for the weeds to take up and hence it would not provide weed control. Herbicides with higher binding are generally considered less mobile as there is a lower amount of herbicide in the soil moisture phase at any given time – although this lower concentration of herbicide in the soil moisture may still move with soil moisture.

Weed control

All pre-emergent herbicides require some soil moisture to be effective. Ideally the season break should be adequate to move herbicide into the soil and then keep the soil surface moist for the weeks following, without rainfall being too excessive and resulting in unexpected deep movement.

The situations where weed control may be compromised are likely to be one of the following:

- The soil surface is dry, however there is enough soil moisture at depth to germinate weeds. This is most likely to be more problematic in soils that have been previously cultivated, and hence have some weed seeds deeper in the profile where the soil is moist. These deeper germinating weeds may not take up enough herbicide when moving through the treated (dry) topsoil.

- A small rainfall event has been adequate to germinate weed seeds, but with no follow up rainfall the soil surface rapidly dries out. Root uptake herbicides with low solubility are particularly affected, as the low solubility means that the herbicide concentration in the limited soil moisture will be very low. Hence uptake into the emerging weed seedlings will be greatly reduced.

- Mobile herbicides can sometimes move too deep in the soil profile following heavy rainfall, especially on light soils when applied to a dry profile. In some situations there may not be enough herbicide remaining near the soil surface after heavy rainfall to control shallow germinating weeds.

Many pre-emergent herbicides are taken up through the roots via herbicide dissolved in soil moisture. As a rule of thumb, herbicides with higher solubility may perform better in situations where soil moisture is low, as it will be easier for these herbicides to enter the roots in adequate concentration. Although even high soluble herbicides will fail if soil is very dry. Conversely, these higher solubility herbicides are also more at risk of causing crop damage should conditions become very wet.

Additionally some, but not all, herbicides can enter germinating weeds directly through the coleoptile node. In low soil moisture situations, herbicides with some level of volatility may be able to move short distances in the air spaces within the soil and come in direct contact with the coleoptile node of germinating weeds. In some soils, this ‘volatility’ may give better performance than non-volatile herbicides under drier conditions. However, the volatilisation process still requires some level of soil moisture, so cannot be relied on in completely dry soils.

Crop safety

Crop safety is a combination of factors:

- Tolerance of the crop to the herbicide at the dose rate reaching the soil

- Vertical separation i.e. planting depth, soil type and rainfall

- Horizontal separation i.e. sowing with knife points and press wheels to move much of the treated soil, and weeds seeds at the soil surface, into the interrow area.

These factors apply equally to dry and conventional sowing, although sometimes dry sowing may result in increased crop injury. This generally is a result of either:

- Inability to maintain the desired planting depth in hard / dry soils

- Furrow walls collapsing and treated soil falling directly over the crop row

- High volume of rainfall occurring at the initial ‘break’, enabling herbicide movement further than expected in very dry soils.

Due to the unpredictability of the opening rainfall, growers seeking to minimise potential for crop injury should look to:

- Select a herbicide with lower soil mobility

- Only use a well set-up knife point and press wheel sowing system

- Ensure correct planting depth is maintained at all times

- Ensure sowing speed is adjusted to suit the soil conditions at application – including maintaining furrow wall integrity and ensuring adequate soil throw into the interrow, but not across into the adjoining crop row. Optimal sowing speed is likely to require adjustment based on different soil types and different soil moisture levels.

Contact details

Contact

Mark Congreve, ICAN

(02) 9482 4930, 0427 209234