Managing herbicide resistant weeds in the summer fallow

Managing herbicide resistant weeds in the summer fallow

Author: Mark Congreve, Independent Consultants Australia Network | Date: 25 Jul 2014

Take home message

If you are dealing with large weed numbers in summer fallow then you haven’t got your strategies for seed bank management under control.

Widespread adoption of zero till farming has seen a species shift to weeds adapted to surface germination.

Over reliance on glyphosate in the fallow is leading to rapid expression of glyphosate resistance.

Integrated weed management strategies are available to manage key species present in the summer fallow through the northern grains region. Growers who have a zero tolerance to weeds producing seeds can drive down seed banks for many weeds to very low levels within 1 to 3 years.

Growers that have the weed seed bank under control will save herbicide costs; have greater rotational flexibility; have greater options to use diverse tactics that would otherwise be cost prohibitive; and by reducing the frequency of herbicide applications, will delay the onset of herbicide resistance.

What are we dealing with in the summer fallow?

The majority of growers have now been managing their summer fallow using zero till principles for at least 15 years. This has seen two significant changes in recent years.

- Species shift. Weeds suited to surface germinating (i.e.do not need to be buried) now dominate the spectrum e.g. the Chloris grasses (windmill and feathertop Rhodes), fleabane and sowthistle

- Herbicide resistance. The reliance on herbicides in the fallow is seeing herbicide resistance rapidly evolve. Many growers have been dealing with Group B resistance for many years however, in more recent years, the discovery of glyphosate (Group M) resistant weeds is becoming common.

Many growers have turned to the use of Group A (fops) and Group B (Flame) to manage grass weeds in fallow however this is likely to be a very short term strategy, as these modes of action develop resistance much faster than glyphosate.

How did we get here?

With any discussion on managing resistance we need to start with the basics and understand why we have the problem in the first place. When herbicides are applied to a weed population there is the potential that some individuals in the population will be resistant to that mode of action, and hence survive the application. If these individuals are allowed to survive and set seed then the population can eventually become dominated by these resistant weeds.

The speed of development of resistance depends upon many factors, however one of the most important is the natural frequency of resistant individuals in the population.

Some herbicide modes of action are much more susceptible to resistance development than others.

Table 1. Years of herbicide application before resistance evolves (Preston et al 1999).

|

|

Some examples^ |

Years |

|---|---|---|

|

A |

Verdict, Targa, Topik, Select, Axial |

6 – 8 |

|

B |

Glean, Ally, Hussar, Flame, Crusader |

4 |

|

C |

Gesaprim, Gesatop, Terbyne, diuron |

10 – 15 |

|

D |

Treflan, Stomp |

10 – 15 |

|

F |

Brodal, Sniper |

10 |

|

G |

Goal, Affinity, Valor, Sharpen |

10 |

|

H |

Balance, Precept, Velocity |

10 |

|

I |

2,4-D, MCPA, Starane, Tordon |

> 20 |

|

K |

Dual, Sakura |

> 15 |

|

L |

Gramoxone, Spray.Seed, Reglone |

> 15 |

|

M |

Roundup |

> 12 |

^ All tradenames are registered trademarks of their respective owners.

Tradenames are provided as examples only to provide readers with an understanding of common herbicides from that herbicide mode of action group.

While it is important to understand the potential for herbicide resistance development, it is also important to understand that these intervals can be substantially extended if growers do not let any survivors return seed to the soil. This will mean that multiple different tactics will need to be employed, including non-herbicide strategies.

Our main targets

While there are a large number of weeds found in the summer fallow, some have become more prevalent than others, and these will be the ones that will be the focus of this paper – as they fit one, or both, of the characteristics above.

In addition to the resistance status it is also important to understand the ecology of the weed to help design a control strategy.

Table 2. Predominant summer fallow weeds in the northern region

|

Weed |

Glyphosate resistance |

Germination |

Seed production & persistence |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Fleabane |

Confirmed and widespread |

Surface germination (0-5mm) preferred. Does not germinate from >20mm. Likes soil to be wet for 2-3 days. Major flushes occur in spring and autumn. Does not commonly germinate in summer. Prefers lighter soils but will grow anywhere, especially where there is little competition. |

Up to 110 000/plant. No seed dormancy. Greater than 90% loss of seed viability within 18 months but some seed remains viable for several years, particularly if buried. |

|

Sowthistle |

Confirmed in 2014. Also high levels of Group B resistance |

Shallow germination (0-20mm). Germinates any time of year following good rainfall (20- 50mm preferred). Favours soils with high water holding capacity. |

Up to 25 000/plant. No seed dormancy. Persistence is short (<12 months) on soil surface but some persists for ~ 30 months with burial. |

|

Fleabane and Sowthistle produce very large volumes of viable seed per plant however most of this seed loses viability within 18 months. So the key to managing these weeds is to run down the seed bank by an aggressive focus on preventing plants from going to seed for a 2 year period. Fleabane quickly develops a large tap root so knockdown control of larger plants is difficult. Fleabane has widespread glyphosate resistance in the northern grains region. With the recent confirmation of glyphosate resistant sowthistle in some northern weed populations, this will change the required approach to fallow management. A particular area for concern are weeds that germinate during the winter crop and then regrow following harvest in spring, at which stage knockdown control of plants with a fully established taproot can be very difficult.

|

|||

|

Feathertop Rhodes grass |

Glyphosate has always been poor. |

Shallow germination (0-20mm). Ideal conditions are > 10mm rainfall + >25oC + light. First to establish on bare soil. |

Up to 6 000/plant. Short dormancy (6-10 weeks). Only persists for ~12 months, even when buried. |

|

Windmill grass |

Glyphosate always been poor. Resistance confirmed |

Prefers lighter soils. Shallow germination (0-20mm). Germinates summer to autumn after >20mm rain event. |

Prolific seeder. Individual plants continue to set seed during the year. Seed heads blown by the wind. Persistence ~12 months. Burial will increase short term persistence. |

|

Feathertop Rhodes grass & windmill grass have very short persistence (~1 year) meaning a concerted effort for 12 months, focusing on no seed going back into the soil, should drastically drive down numbers. Glyphosate (alone or in a double knock strategy) is unlikely to achieve this. Where there are large amounts of seed on the soil surface, or ‘old’ plants are present and herbicide coverage will be compromised, then cultivation to remove the vegetative material and bury the seed may be required. Glyphosate alone, or as a component in a double knock strategy, is unlikely to provide robust, consistent control.

|

|||

|

Barnyard grass |

Frequent. Becoming widespread |

Multiple flushes occur, mainly Sept – Feb after >10-20mm rain event. Mostly germinates from 0-20mm depth but a small amount can germinate from 10cm. |

Up to 40 000/plant. Flowers with shortening day length. Spread by surface water movement. Doesn’t germinate until the following season. Persists 1-3 years on the soil surface but much longer when buried. |

|

Barnyard grass germinates from multiple flushes following rainfall events in spring and early summer and this, combined with 12 month seed dormancy, makes barnyard grass one of the more persistent summer fallow weeds. The recent and widespread development of glyphosate resistance is making this problem even more difficult and costly to manage. Double knock applications of glyphosate followed by paraquat approximately 7 days later are still typically providing control, even on populations that have low levels of glyphosate resistance, provided that care is taken with application timing. The first application needs to be applied to very small weeds under ideal spraying conditions (no moisture stress) with the second paraquat application being applied approximately 5-7 days later. Always use maximum rates and don’t delay the first application waiting for further germinations. Use the second paraquat application to take care of these. As glyphosate resistance continues to develop, or plants have begun tillering, alternate strategies will need to be employed.

|

|||

|

Liverseed grass |

Resistance confirmed. Not currently widespread. |

One main flush in spring after >20mm rain event. Frequently germinates from 50mm and will germinate from 100mm depth. |

Up to 3 000/plant. Persistence on soil surface was 24% after 1 year and <0.1% after 4 years. Burial will increase persistence in short term but also stimulates germination. |

|

Liverseed grass is somewhat different from other fallow weeds discussed in this paper as it will germinate from 50 to 100mm depth; therefore burial is unlikely to be a useful strategy. Glyphosate resistance is present is some fields, however is not yet widespread so single applications of glyphosate are often still providing good control. However, as glyphosate resistance is present in the northern region, always follow with a paraquat double knock application approximately 7 days later to ensure high levels of control are achieved and help delay glyphosate resistance. As most liverseed grass typically germinates in a single flush in spring / early summer after a substantial rainfall event, it may be possible to time a pre-emergent application of Dual® Gold before a forecast germinating rainfall event in spring, prior to planting sorghum or maize in early summer.

|

|||

Developing a control strategy for the summer fallow

By having a good understanding the effectiveness of control tactics available and looking for weaknesses in the ecology of the weed that can be exploited, integrated control strategies designed to aggressively drive down the weed seed bank in the soil can be developed.

In fallow situations, the lack of crop competition places additional importance on the effectiveness of other strategies.

Control in the winter crop is one of the major strategies to managing weeds in summer fallows. Weeds such as fleabane and sowthistle can germinate in early in the winter crop or in spring prior to harvest. Some of the summer grasses can also germinate on spring rainfall well before harvest, especially where gaps in the crop canopy allow light onto the soil surface. If these weeds establish before harvest, they can be extremely difficult to control after harvest.

Fleabane is a prime example. Germinations can occur in autumn and early winter. If not controlled in the crop the fleabane will continue to develop a large tap root, even if the above ground size is limited by competition from the crop. Registrations are now in place for the use of Amicide® Advance 700 (knockdown) or FallowBoss® Tordon® (knockdown and residual) in winter cereals.

For crops such as chickpeas there are very limited post emergent options so the key to preventing weeds being present at harvest is to ensure a robust pre-emergent strategy is implemented. A tank mix of Gesatop® and Balance applied at planting should provide control of the majority of key weeds until harvest.

Farm hygiene can be a low cost, but highly effective tactic in preventing new weed incursions into the paddock. Livestock can introduce weed seeds on their coat or in their stomachs; weeds can come in through hay and animal feed; weed seeds can be in farmer saved planting seed that has not been properly cleaned; dirty farm machinery and farm utes are an additional source of weed seeds; as is water flow across the paddock from flooding.

Strategies to reduce new weed introductions include: make sure fencelines, roadsides, tracks and around machinery sheds are kept clean of weeds; pay particular attention to weeds on perimeters of paddocks; always feed hay and other stock feed in a yard or small paddock close to facilities and monitor and remove weed germinations coming from the feed source; if livestock are fed hay and other fodder that may contain weed seeds, keep them in a small paddock for a week to allow the majority of weed seed to pass through before turning them out onto cultivation paddocks; always have planting seed graded to remove weed seeds; harvest from the cleanest paddocks to the dirtiest, and then clean down; always clean down contractors machinery before entering the paddock; if machinery breaks down in a paddock and has to be dismantled for repairs (and weed seeds are likely to be dislodged) then GPS mark the site and come back over the next 1-2 years and control weed escapes.

Knockdown herbicides have been the most common tactic employed in zero till fallows and are likely to continue to be the main strategy; however the simplicity of using glyphosate for ‘just about everything’ has to change.

The use of double knock program is increasing, either to control resistant weeds or those that require more than a single application to achieve the high levels of control desired. The first application is likely to be a systemic herbicide (typically Group A, Group I, Group M) followed by a contact herbicide (typically Group L).

Tips for effective double knock herbicide applications:

Initial application:

An effective double knock needs the first application to do the bulk of the work. If the herbicide selected is not likely to give at least 90% control as a single application then the doubleknock is probably unlikely to be effective.

- Target small weeds, especially with glyphosate resistance.

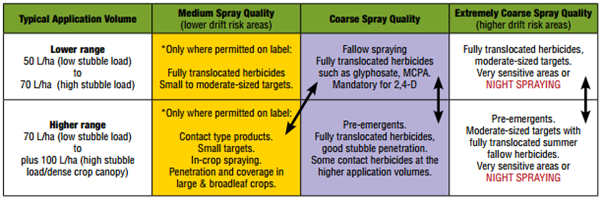

- Coarse droplet spectrum (required for drift reduction) dictates that water rates will need to be high (50L to 100L/ha) to have enough droplets for effective coverage. If using extremely coarse spectrum then water rates need to increase further.

Source: GRDC Nozzle Selection - Back Pocket Guide

Recommended spray quality x herbicide

| |

F |

M |

C |

VC |

XC |

|

|

Fop’s & Dims (A) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Imi’s (B) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Triazines (C) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DNA’s (D) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Phenoxy’s (I) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pyridines (I) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Glyphosate (M) |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Nufarm Spraywise®

- Systemic products require good application conditions i.e. small weeds and not moisture stressed.

- Shallow rooted grass weeds (e.g. feathertop Rhodes, windmill, barnyard grass) will quickly become moisture stressed in summer. Weeds that ‘freshen up’ following morning dew and cooler temperatures are still moisture stressed.

- Don’t delay application, waiting for further germinations – the second knock will take care of these.

- Tank mixes

- Don’t apply mixtures that will compromise the efficacy of the initial application. Use the second knock to clean up the rest of the spectrum.

- Known mixtures to avoid include:

- Group A herbicides and Group I herbicides (e.g. Verdict® + Uptake® with 2,4-D)

- Products requiring oil based adjuvants with glyphosate when targeting grass weeds

- 2,4-D with glyphosate when targeting sowthistle.

Second application:

The second application is designed to ‘finish off’ any weeds not completely controlled by the first application and to pick up any escapes from the first application, especially if they are resistant to the first mode of action.

- Spray in the opposite direction. This may pick up weeds that were physically shaded in the first application.

- When applying contact herbicides, coverage of the target is critical. If using a medium/coarse droplet spectrum high carrier rates are recommended. Use of an extremely coarse droplet spectrum is not recommended as the water rates required to maintain coverage become impractical.

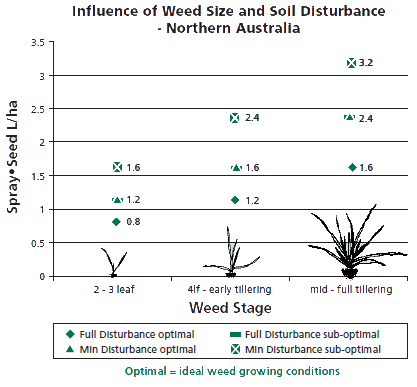

- Herbicide and water rates for Group L herbicides are dependent upon weed size.

- The Spray.Seed® label recommends the following water rates for application in summer rainfall areas

|

Small plants (2 to 5 leaf) and well separated |

50 to 100L/ha |

|

5 leaf to early tiller / rosette; 30 to 50% ground cover |

100 to 150L/ha |

|

Advanced growth; dense and/or tall weed stands |

150 to 200L/ha |

|

Very dense and tall weed growth |

Split applications @ 150L/ha |

Extra wetter is required when water volumes exceed 100L/ha.

- Apply the correct rate for the situation.

Syngenta SPRAY.SEED Stewardship Module

- Where a residual herbicide is to be added, generally it is more practical to include it in the second application as compatibility is usually better. The main exception is likely to be where there is rainfall forecast between applications where the rainfall can be utilised for residual herbicide incorporation and/or there is a risk of delay to the second timing.

Specific double knock situations

Glyphosate followed by paraquat or Spray.Seed may still be effective when initial low levels of glyphosate resistance are observed, however only on very small weeds and full label rates of both applications should be used. For the initial glyphosate application, do not tank mix 2,4-D when targeting sowthistle or oil based adjuvants when targeting grass weeds.

For grass weed targets, time applications approximately 5 to 7 days apart. For broadleaf weeds best results are seen from applications approximately 7 to 10 days apart.

Group I followed by paraquat or Spray.Seed . For broadleaf weeds such as fleabane or sowthistle use a Group I (2,4-D, FallowBoss Tordon, Tordon 75-D – check labels for rates and use situations) followed by paraquat or Spray.Seed. The addition of glyphosate in the first pass generally increases control of fleabane but reduces control of sowthistle.

Target small weeds (less than 1 month old). Reliability of control decreases on older plants, particularly fleabane. Time applications approximately 7 to 10 days apart.

Group A followed by paraquat . Two permits are currently are in place for fallow applications:

- PER13460 for quizalofop against windmill grass. Application rate is equivalent to 250 to 500mL/ha of Targa®bolt (200g/L) + Hasten® at 1L/ha. This use is restricted to NSW only.

- PER12941 for haloxyfop against feathertop Rhodes grass. This use is restricted to Queensland only and only preceding a mungbean crop.

In both cases, the use must be followed by a double knock of 250g/L paraquat of at least 1.6L/ha for resistance management and only one application is permitted per season. Activity is currently underway to expand registrations. However the constraint of only one double knock per fallow is expect to remain, so growers need to ensure this application is timed for maximum impact.

Paraquat followed by paraquat . While this is not a double knock for resistance management, under certain situations the use of two sequential paraquat applications can be beneficial. In particular, when dealing with grass weeds when conditions are not suitable for a systemic herbicide (e.g. glyphosate or Verdict) as the weeds are moisture stressed. Waiting for rainfall to freshen up the grass weeds is likely to see weeds develop to the point where they will not be adequately controlled by standard double knock options. In this situation, a better strategy is to apply paraquat as the first application followed by a second paraquat 14-21 days later when weeds start to show signs of any regrowth.

Optical (camera) sprayers e.g. WeedSeeker®, WeedIT® can be highly effective in providing economical control of low density populations in the fallow. Additionally, registration of high application rates by this technique may allow the control of resistant weeds that have survived a preceding application of a different mode of action.

Nufarm have recently received the following product registrations for use with the optical spot spraying technique:

|

|

Barnyard grass |

Fleabane |

Sowthistle |

Bladder ketmia |

Caltrop |

Turnip weed |

Australian bindweed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nuquat® 250 |

3-9 L/ha |

6-9 L/ha |

6-9 L/ha |

3-9 L/ha |

3-9 L/ha |

6-9 L/ha |

9 L/ha |

|

Trooper® 75-D |

|

2 L/ha |

2-4 L/ha |

|

1-2 L/ha |

|

|

|

Comet® 400 |

|

1-3 L/ha |

1-3 L/ha |

|

1-3 L/ha |

|

|

|

Amicide® Advance 700 |

|

4-8 L/ha |

4-8 L/ha |

|

4-8 L/ha |

|

|

|

Amitrole T |

|

5-8 L/ha |

5-10 L/ha |

|

5-10 L/ha |

|

|

In addition to the above registrations, APVMA Permit 11163 is in place to allow users to apply a range of other herbicides via this technique, including glyphosate; paraquat; paraquat + diquat; amitrole + paraquat; glufosinate; amitrole T; 2,4-D; triclopyr; fluroxypyr; quizalofop; haloxyfop, sethoxydim; clethodim; butroxydim; and fluazifop. See permit for application rates and use situations. However note that this permit is currently due to expire on 28th February 2015.

With glyphosate becoming increasingly less effective, paraquat having weed size limitations and Group A herbicides limited to one application per fallow, growers are going to need additional strategies that do not solely rely on knockdown herbicides. Other useful strategies to consider include:

Monitoring is a critical step in weed management that is often overlooked. Following any treatment, always come back and check the paddock to ensure that the treatment is working the way it is expected.

Residual herbicides can be an excellent option to introduce a different mode of action and take some of the pressure off knockdown herbicides. Consider treating at least some of the fallow paddocks with a residual herbicide to take the time demands off double knock spray applications, especially in paddocks where the next crop rotation is known.

Some of the main pre-emergent herbicides available for use in the northern region include:

|

Group |

Herbicide |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

B |

Imazapic (e.g. Flame®) for grass and broadleaf weed control |

Extremely persistent requiring temperature and lots of moisture to breakdown. Persists even longer with soil pH <6.5. Crop rotation restrictions may limit planting to legumes or Clearfield® varieties Avoid overuse. Group B is extremely prone to development of resistance. |

|

C |

Triazines (e.g. Gesaprim®, Terbyne®) provide mainly broadleaf control with some grass activity in certain situations |

Mainly used preceding sorghum or maize crops. Persistence can be moderate to long which may prevent some rotational options the following winter (see labels), especially with high application rates. Speed of breakdown is reduced on alkaline soils so persistence in the soil increases. |

|

D |

DNA herbicides (e.g. Stomp®, Treflan®) provide grass and some broadleaf control |

Mainly used preceding legume crops. Very persistent however binds tightly to the upper soil so crop selectivity is often achieved by planting below the herbicide band. Potential crop rotation constraints if double cropping a cereal into a paddock treated with Group D herbicides prior to a short season summer pulse such as mungbean. Requires mechanical incorporation to reduce volatilisation. |

|

H |

Isoxaflutole (e.g. Balance®) provides pre-emergent control of important fallow weeds such as fleabane, sowthistle and feathertop Rhodes grass |

Provides long residual control however early spring applications should allow for planting of chickpeas or cereals the following winter under normal situations (see label). Can be applied to dry soil however requires rainfall to move into the zone of germinating weeds. |

|

I |

Pyridine herbicides (e.g. FallowBoss Tordon) provide residual control of some broadleaf weeds including fleabane |

Can be applied early in the fallow prior to summer sorghum or cereals the following winter. Also provides knockdown activity on some weeds. Crop rotation restrictions exist for pulses and other broadleaf crops. |

|

K |

s-metolachlor (e.g. Dual) for grass and some broadleaf weed control |

Application prior to planting sorghum, maize or some broadleaf crops will provide grass weed control and control of some small seeded broadleaf weeds. Relatively short persistence. Unlikely to have crop rotational constraints the following winter. Should be incorporated by rainfall or cultivation within 7 to 10 days to reduce losses from photodegradation and volatility. |

Cultivation has increased in frequency on a number of farms in recent years, especially where growers are dealing with ‘blow outs’ due to herbicide failure from resistance; or the lack of ability to apply knockdown herbicides in a timely manner, often due to climatic constraints or lack of spraying capacity.

While cultivation is generally seen as an ‘option of last resort’ in zero till systems it can be an effective tactic against shallow germinating weeds and may also be incorporated into other farming system requirements such as pupae busting , deep placement of nutrients or when paddock renovation is required.

If cultivation is to be contemplated, then consider the following:

- Where there is large amounts of vegetative material on the paddock herbicide coverage may be compromised, so burial of the above ground material may result in better coverage of subsequent applications

- Cultivate on a drying profile. This will minimise surface zone compaction and the ‘transplanting’ of weeds

- Weeds such as fleabane, sowthistle and feathertop Rhodes, windmill and barnyard grasses prefer to germinate on, or near, the soil surface. Burying seeds greater than 5cm (10cm for barnyard grass) is likely to prevent these seeds from emerging. However

- Burying seeds generally increases their persistence and reduces the rate of natural mortality. The exception is the Chloris species (windmill grass and feathertop Rhodes grass) where seed mortality is ~12 months, regardless of whether it is left on the soil surface or buried

- Unless using a mouldboard plough set up with soil skimmers, weed seed is likely to be distributed at a range of depths, which may still allow a proportion to emerge

- If multiple cultivation passes are undertaken then mixing of the seed will occur throughout the profile

- Any future tillage undertaken before final seed mortality will bring some seed back up towards the surface and enable germination and weed emergence.

- Cultivation method will affect the proportion of seed buried to different depths

- Regardless of the cultivation technique employed some seed will always remain within the germination zone so these weeds need to be controlled to prevent the population regenerating. One of the best strategies to manage this is application of a residual herbicide with incorporation undertaken by the last cultivation pass in a multiple cultivation scenario; or applied after the cultivation but just before the next rainfall event, where rainfall is being used for incorporation.

Patch management techniques can be implemented when small patches of weeds have been identified. Mark these patches with GPS coordinates and take an active strategy to remove existing weeds before flowering and continue to monitor for subsequent germinations until the seed bank has been exhausted. Patch management tactics could include chipping or hand rogueing, spot spraying with an effective herbicide, or spot cultivation.

Growing a summer crop , rather than maintaining a fallow, could be a consideration in some situations. For example, growing a summer legume such as mungbean or soybean may allow growers to tackle a paddock with a summer grass weed problem. The option of a pre-emergent herbicide, crop competition and selective post-emergent herbicide from a different mode of action is likely to drive down weed numbers more than multiple fallow sprays of a single mode of action knockdown herbicide.

Likewise, if broadleaf weeds such as fleabane are a problem in the paddock, then a summer crop of sorghum allows the use of robust pre and post-emergent herbicide options.

If growing a summer crop for weed management, keep row spacing narrow to maximise competition from the crop and prevent light from reaching the soil surface, always use the maximum registered rate of pre-emergent herbicide to get the maximum length of control and avoid situations where there are limited reliable post-emergent options to control any subsequent emergence. For example, don’t grow sorghum in a paddock with grass weed problems as it is likely that the pre-emergent herbicides will run out of residual before harvest and no effective post-emergent options are available for over the top application.

Careful and thorough attention to preventing weed set seed in the fallow can quickly drive down the seed bank of most of our problematic weeds in the fallow. However, if weeds are allowed to return seed to the soil during the fallow phase then weed numbers are likely to continue to increase over time. Growers that have the weed seed bank under control will save herbicide costs; maintain crop rotational flexibility; be able to use diverse tactics that would otherwise be cost prohibitive; and by reducing the frequency of herbicide applications, will delay the onset of herbicide resistance.

Contact details

Name Mark Congreve

Organisation Independent Consultants Australia Network

Phone 0427 209234

Fax 02 9482 4931

Email mark@icanrural.com.au

® Registered Trademark.

This publication has been prepared in good faith on the basis of information available at the date of publication. Neither the Grains Research and Development Corporation or Independent Consultants Australia Network Pty Limited or other participating organisations guarantee or warrant the accuracy, reliability, completeness or currency of information in this publication or its usefulness in achieving any purpose. Readers are responsible for assessing the relevance and accuracy of the content of this publication. Neither the Grains Research and Development Corporation or Independent Consultants Australia Network Pty Limited or other participating organisations will be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information in this publication. Products may be identified by proprietary or trade names to help readers identify particular types of products but this is not, and is not intended to be, an endorsement or recommendation of any product or manufacturer referred to. Other products may perform as well or better than those specifically referred to.

Reviewed by John Cameron

GRDC Project Code: ICN00016,