Chickpea and mungbean research to maximise yield in northern NSW

Author: Leigh Jenkins(1) and Andrew Verrell(2) | Date: 25 Feb 2015

1 Trangie Agricultural Research Institute, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Trangie NSW 2823

2 Tamworth Agricultural Institute, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Tamworth NSW 2340

Take home messages

- When sowing chickpea within the optimum sowing window (mid May – early June):

for yield potential ≥ 1.5 t/ha - sow at ≥ 30 plants/m2,

for yield potential ≤ 1.5 t/ha - sow at ≥ 20 plants/m2. - When sowing chickpea very late (not recommended) consider sowing at the higher target plant density, to compensate for potentially poorer establishment.

- Mid-late May should be considered the optimum sowing window for chickpeas. A substantial yield penalty is likely to be incurred when sowing is delayed until mid-late June.

- Kabuli chickpea types can have equal yield potential to desi types if sown early, but greatly reduced yields if sowing is delayed.

- An optimum plant density of at least 30 plants/m2 for mungbeans is recommended under irrigated conditions, with further research required to justify an increase to 35 or 40 plants/m2.

Introduction

Chickpea (a winter-grown pulse crop) makes a significant contribution to the northern farming systems region as a key rotation crop for both winter and summer cereal production. Mungbean (a summer-grown pulse crop) is considered more of an “opportunity” crop in the northern region when adequate rainfall or irrigation conditions are available. Both pulse crops, as well as being viable (profitable) in their own right, contribute to nitrogen fixation, disease control, weed control and herbicide resistance management when used in cereal crop rotations.

The Northern Pulse Agronomy Initiative (NPAI) project was established in 2012 with the specific goal of achieving greater adoption, productivity and profitability of summer and winter pulse crops in the Northern Grains Region. A key output of this project is the development of improved agronomic management strategies to achieve seasonal yield potential and grain quality.

This paper provides an update on some of the recent research trials being conducted by NSW DPI in the Western Plains region for both a winter pulse crop (chickpea) and summer pulse crop (mungbean). The common theme of these trials is to investigate management aspects which maximise yield potential.

1. CHICKPEA – Optimum plant density targets to maximise yield

Current advice from both NSW DPI (Matthews et al, 2014) and Pulse Australia (Cumming & Jenkins, 2011) consistently recommend a target plant population of 20-30 plants/m2 for the northern region of NSW. It is suggested that a population of 25 plants/m2 will optimise yields in the northern region, with slightly higher or lower target populations (i.e. still within the range of 20-30 plants/m2) allowing for establishment conditions at the time of sowing.

These recommendations have been endorsed through a series of variety x plant density factorial experiments conducted by NSW DPI across central and northern NSW since 2011, with previous results up to 2013 reported at the 2014 Updates (Verrell et al, 2014). This series of trials has been continued in 2014 to achieve greater cross-seasonal validity.

Methods

In 2014 five chickpea varieties – PBA Boundary, PBA HatTrick, Kyabra, CICA0912, and CICA1007 – were sown at six target densities of 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 and 45 plants/m2. The variety treatment CICA0912 has been excluded from these results due to a seed supply issue. In this paper only the main effect of yield response to plant density will be reported.

The Coonamble site was sown on a grey vertosol soil on May 24 with adequate moisture conditions at sowing. Growing season rainfall in 2014 (162 mm) was below the long term average (LTA = 179 mm) with October only receiving 5 mm (LTA = 42 mm).

The Trangie site was sown on a red brown chromosol soil on May 28 into good moisture conditions at sowing. The crop received only 130 mm during the growing season, well below LTA (180 mm). September and October were very dry with falls of 9.8 mm and 2.6 mm respectively, compared to long term averages of 31.4 mm and 45.7 mm respectively.

In addition to lower than average rainfall, potential yield at the two sites was reduced due to both flower abortion caused by frosts and cold periods during flowering, and pod abortion due to moisture stress/terminal drought during grain fill.

Results

The response of grain yield to increased target plant density at Coonamble and Trangie sites are shown in Figures 1 and 2 respectively. Actual plant densities achieved were slightly below target at Coonamble site (average 82%) and slightly above target at Trangie site (average 111%) based on plant count data (not included here).

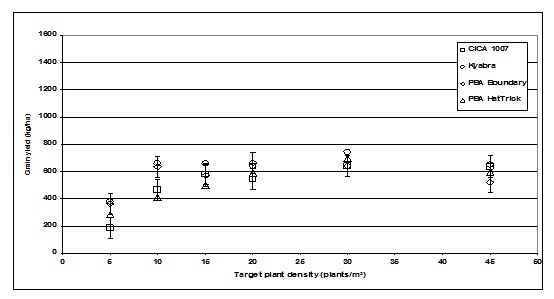

Figure 1. The effect of plant density on chickpea grain yield at Coonamble, 2014 (s.e. 77.21 kg/ha)

At the Coonamble site the response of grain yield to plant density was significant from 5 to 15 plants/m2, resulting in a 90% increase in yield from 301 kg/ha to 576 kg/ha (averaged for all varieties). Response at higher plant density was flat (i.e. not significant) from 15 to 45 plants/m2. The maximum plot yield achieved at Coonamble site in 2014 was 740 kg/ha. This trend is consistent with previously reported 2012 and 2013 Coonamble results (yield ≤ 1.5 t/ha), whilst in 2011 (yield ≤ 3.5 t/ha) there was a significant increase in yield at higher plant density up to 45 plants/m2 (Verrell et al, 2014).

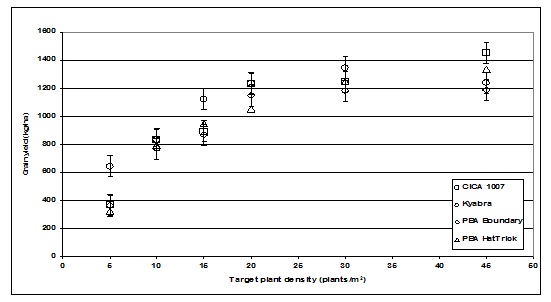

Figure 2. The effect of plant density on chickpea grain yield at Trangie, 2014 (s.e. 76.238 kg/ha)

At the Trangie site the response of grain yield to plant density was significant from 5 to 30 plants/m2, resulting in a 195% increase in yield from 425 kg/ha to 1256 kg/ha (averaged for all varieties). There was only a slight response (i.e. not significant) from 30 to 45 plants/m2. The maximum plot yield achieved at Trangie site in 2014 was 1454 kg/ha. This trend is also consistent with previously reported 2013 Trangie results where optimum yield was achieved at around 30 plants/m2 (Verrell et al, 2014)

Conclusion – Chickpea plant density

These two trials have confirmed the relationship between rainfall-limited yield potential, optimum plant density and yield response as follows:

- When sowing chickpea within the optimum sowing window (mid May – early June):

for yield potential ≥ 1.5 t/ha - sow at ≥ 30 plants/m2

for yield potential ≤ 1.5 t/ha - sow at ≥ 20 plants/m2 - When sowing very late consider sowing at the higher target plant density

2. CHICKPEA – Optimum sowing window to maximise yield

Choosing the optimum sowing time for chickpeas is a compromise between maximising yield potential and minimising disease levels. Earlier sowing can increase the risk of Ascochyta and Botrytis grey mould (BGM) disease, lodging, and soil moisture deficit during grain fill. Later sowing can attract increased heliothis pressure and lead to harvesting difficulties, but may reduce exposure to Ascochyta and Phytophthora infection events and lessen the risk of BGM (Matthews et al, 2014).

Chickpea time of sowing trials were conducted by NSW DPI at Trangie in 2010, 2011 and 2012, to evaluate the impact of sowing date on phenology and yield of current and potential release cultivars. The 2010 trial succumbed to in-crop waterlogging and wet weather at harvest and was not harvested. The results of the 2011 and 2012 trials were reported at the 2013 Updates (Jenkins and Brill, 2013). For currently grown chickpea varieties with a mid-season (Jimbour type) maturity such as PBA Boundary and PBA HatTrick, optimum yields were achieved from mid May to early June sowing. Planting chickpeas in mid-late June produced significantly lower yields in both the 2011 (wet year) and 2012 (dry year) trials at Trangie.

A much simpler trial was planted at Trangie in 2014 which demonstrates the comparative impact of time of sowing on desi vs. kabuli varieties of chickpea.

Methods

In 2014 fifteen desi types and five kabuli types of chickpea varieties were planted at two sowing dates. Time-of-sowing 1 (TOS 1) was planted on May 28 under the same conditions described above for the Trangie chickpea x plant density trial, whilst time-of-sowing 2 (TOS 2) was planted three weeks later on June 19. TOS 2 was sown into marginal seed-bed conditions, and received no significant follow-up rainfall until mid-July. In this paper only the main effect of yield response based on chickpea type (i.e. desi vs. kabuli) to time of sowing will be reported.

Results

The comparative grain yield response of desi and kabuli types of chickpea to time of sowing at Trangie site is shown in Figure 3. It should be noted that establishment was reduced by the delayed sowing time, with all varieties in TOS 1 achieving an average plant density of 32 plants/m2, compared to only 25 plants/m2 for TOS 2, a reduction of 22% (based on plant count data, not included here). Sowing rates were calibrated for seed size of each individual variety but otherwise unchanged between sowing dates (target plant density 35 plants/m2).

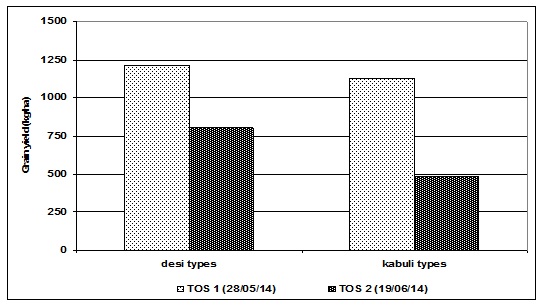

Figure 3. The effect of time of sowing on desi and kabuli chickpea grain yield at Trangie, 2014

(data not analysed at time of publication)

The graph shows the potential grain yield of current desi vs. kabuli types to be similar when sown at what is considered to be an optimum sowing time for chickpea (i.e. mid-late May). For TOS 1, averaged across all varieties within each group, desi types yielded an average of 1216 kg/ha and kabuli types yielded only 7.5% less at an average of 1125 kg/ha (TOS 1 mean 1193 kg/ha).

The three week delay in sowing until mid June resulted in reduced grain yield, with the kabuli types appearing to be affected to a greater degree than desi types. For TOS 2, averaged across all varieties within each group, desi types yielded an average of 804 kg/ha and kabuli types yielded an average of 486 kg/ha (TOS 2 mean 724 kg/ha). This yield loss equated to 34% for desi types, 57% for kabuli types, and an overall grain yield reduction of just on 40% between TOS 1 and TOS 2.

Contributing factors to the decline in yield between TOS 1 and TOS 2 could have included more marginal conditions at sowing, resulting in reduced establishment, and delayed phenology development, resulting in an inability to compensate for adverse environmental conditions during the flowering period (i.e. frost events, cold periods, and greater exposure at critical development stages to moisture stress).

Conclusion – Chickpea time of sowing

This trial has confirmed earlier research suggesting that mid-late May should be considered the optimum sowing window for chickpeas in this region. A substantial yield penalty is likely to be incurred when sowing is delayed until mid-late June. Kabuli types will have equal yield potential to desi types if sown early, but greatly reduced yields if sowing is delayed. This trial also confirms the conclusion above that a higher sowing rate should be considered if late sowing cannot be avoided, to compensate for potentially poorer establishment.

3. MUNGBEAN – Optimum plant density targets to maximise yield

Relative to other crop species, mungbean is a very short duration crop (90 – 120 days). Because there is little time for the crop to compensate for any adverse factors within that timeframe, establishing a uniform plant density is critical to achieve uniform plant maturity across the paddock. NSW DPI recommends an established density of 20 – 30 plants/m2 for dryland crops and 30 – 40 plants/m2 under irrigation situations (Moore et al, 2014).

Whilst these recommendations are generally applicable to the northern grains region, there has been no recent research in northern NSW to validate these guidelines for the newer varieties of mungbeans currently being grown. Under the NPAI project summer pulse trials commenced in the 2013-14 summer crop season with a simple trial to investigate the impact of plant density on grain yield of mungbean; a row spacing component has been added to this trial for the current 2014-15 season.

Methods

In 2013-14 three mungbean varieties – Berken, Crystal, and Jade_AU – were planted at four target densities of 20, 30, 40 and 50 plants/m2. Sowing rates were adjusted for each variety and target density based on individual seed size and germination test results. In this paper only the main effect of yield response to plant density will be reported.

The Trangie site was sown on a grey vertosol soil on 17 Dec into good moisture conditions at sowing. The trial site was irrigated and received a total of 216 mm rain and 5.5 ML/ha in seven irrigation events (including pre-water) during the growing season. Insect pressure was relatively light with three insecticide applications through the season (helicoverpa and brown vegetable bug). The trial was desiccated then harvested on 17 April (121 days post-sowing).

Results

Plant count data (not included here) showed a much higher establishment percentage than was anticipated, with an overall trial mean of 147%. Sowing rates for each variety were based on individual seed size and an allowance of 80% to account for germination and field conditions. Actual plant densities achieved were 31, 46, 57 and 70 plants/m2 for the target densities of 20, 30, 40 and 50 plants/m2 respectively.

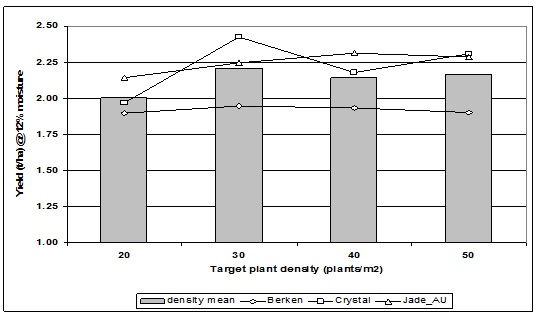

Grain yield response to increasing plant density is shown in Figure 4. Note this data has not been statistically analysed at time of publication. However averaged across all varieties, there appears to be little to no response in mungbean grain yield as plant density is increased, under irrigation conditions. The older variety Berken showed a very flat (i.e. nil) response. The two newer varieties, Crystal and its more recent replacement Jade_AU, suggest a slight response with an optimum target density between 30 and 40 plants/m2. Mean grain yield for this trial was 2.13 t/ha (averaged across all varieties and treatments). For comparison, the companion mungbean variety trial planted at the same time was sown using a target density of 35 plants/m2 and achieved a mean grain yield of 1.73 t/ha (data not included in this report).

Figure 4. The effect of plant density on mungbean grain yield at Trangie, 2014

(data not analysed at time of publication)

Harvested seed size appeared to show no response to increasing plant density in this trial (data not shown). The older Berken variety had the smallest seed size of the three varieties (average 6.53 g/100 seeds); whilst Crystal and Jade_AU were slightly larger at 7.06 and 7.17 g/100 seeds respectively.

Conclusion – Mungbean plant density

This trial has confirmed an optimum plant density of at least 30 plants/m2 for mungbeans under irrigated conditions, but was inconclusive as to whether there is any significant yield response from targeting a higher rate of 40 plants/m2. The trial has been replanted in the 2014-15 season to further investigate both plant density and row spacing configurations on mungbean grain yield.

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this Northern Pulse Agronomy Initiative project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the authors would like to thank them for their continued support.

Thanks to Jayne Jenkins, Scott Richards, Michael Nowland, and Dana Burns (all NSW DPI) for their technical assistance with trials. Thanks also to Jason Peters (“Woolingar”, Coonamble) and Kelvin Appleyard (NSW DPI, Trangie) for their cooperation in providing trial sites and overall crop management for these trials.

References

Cumming, G. and Jenkins, L. (2011) Chickpea: Effective crop Establishment. Pulse Australia, Northern Pulse Bulletin, PA 2011 #07.

Jenkins, L. and Brill, R. (2013) Chickpea time of sowing trials update, Trangie 2011 and 2012. Proceedings, 2013 Grains Research Update, Coonabarabran, 26-27 Feb 2013.

Matthews, P., McCaffery, D. and Jenkins, L. (2014) Winter crop variety sowing guide 2014. NSW DPI Management Guide.

Moore, N., Serafin, L. and Jenkins, L. (2014) Summer crop production guide 2014. NSW DPI Management Guide.

Verrell, A., Brill, R. and Jenkins, L. (2014) The effect of plant density on yield in chickpea across central and northern NSW. Proceedings, 2014 Grains Research Update, Coonabarabran, 26-27 Feb 2014.

Contact details

Leigh Jenkins

NSW Department of Primary Industries

Mb: 0419 277 480

Email: leigh.jenkins@dpi.nsw.gov.au

GRDC Project Code: DAN00171,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK