Profitable dual purpose cereals in the north and central west (A Purlewaugh case study)

Profitable dual purpose cereals in the north and central west (A Purlewaugh case study)

Author: Robert Freebairn, Agricultural Consultant, Coonabarabran | Date: 23 Feb 2016

Take home message

Dual purpose crops can be a vital part of a mixed business farming operation. Reliable dual purpose crops require a high standard of agronomy including timely sowing, careful choice of variety, good sub soil moisture, and high soil fertility.

Role of dual purpose cereals on our property

Dual purpose winter crops, or grazing only ones, can regularly gross $1000 -$1500/ha with costs typically $300 - $350/ha. Plus they take a lot of pressure off the remaining grazing base (pastures) commonly giving them a chance to get away and be in an improved position to provide good feed when dual purpose crops are locked up for grain.

Dual purpose crops supply quality feed in good quantities when other pastures are growing at a slow rate, especially in years with dry autumns (five of the last six years).

For our property, 30 km east of Coonabarabran , 20 percent of the farm is sown to dual purpose crops each late summer early autumn, 30 percent is tropical grass based (aim for 50 percent) and 50 percent is improved native grass based. In both native and tropical grass pastures winter legumes are an important part of the pasture.

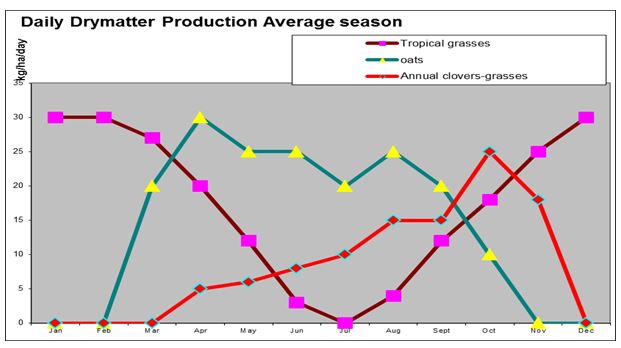

Figure 1. Daily drymatter production in an average season

Profitability

On a light acid soil farm in a 625mm rainfall area, projected GM for 2015/16 is $409/ha (based on 200 steers turn-off with margin gain of $800/beast). Stocking rate 7 DSE/ha.

Pasture fertiliser cost/ha for the pasture area is $40. Winter forage cropping cost (60/ha) $300 - $350/ha. Costs Include seed, DAP, Urea, sowing, seed, weed (including fallow) and insect control.

Winter forage crops can return over $1350/ha (100 -150 days grazing x 1.2 kg/beast/day x $3kg plus grain recovery in seasons with good springs, averaging 2.0 t/ha) and most years gross $1000/ha or better.

Other than dry-lick no supplementary feeding is practised. Drought strategy is stock down and quickly rebuilds when good conditions occur.

Sow early critical

Often the difference between early sowing and missing that opportunity is the difference between good winter feed and poor winter feed. Early sown crops onto subsoil moisture can generally survive for months if no follow up rain occurs and then provide almost instant feed when rain does eventually fall.

Being able to sow early and reliably (high probability of successful establishment) is critical for almost guaranteeing a high quality reliable winter feed supply.

For us that can mean sowing as early as 20th February, as we did in 2014, but in other years that will be too hot for a reliable establishment. To maximise the probability of sowing early sowing with minimal soil disturbance, press wheels and if available a lighter soil paddock all improve probability of early sowing success. Good sub soil moisture plus stubble cover also helps with reliable early establishment.

That’s a challenge as late summer and autumn rains are so unreliable. Probabilities of achieving this outcome improve dramatically if one can realistically establish crops on a very minimal rainfall event.

One pitfall of sowing early is that summer weeds like annual summer grasses can also germinate with the crop. Where winter crops are being sown as part of a strategy to clean up paddocks for future pasture sowing, that can be a problem, especially after a drought as little opportunity occurs to control fallow weeds that can keep germinating until mid autumn.

Temperature and temperature forecast important

We use the guide that if mean daily temperature (average of maximum and minimum) is 23oC or less and not likely to rise it is a reasonable bet to sow if soil moisture is ok (little hard data to support this claim). This is a better guide than choosing a date (such as early March for our area). Sometimes we sow as early as 20th February and in other years as late as mid-April.

Sowing rainfall probability. CliMate best guide

Being able to sow and achieve germination on a minimal rainfall event is critical. For example according to the App “CliMate” the odds of receiving 10mm or more within a three day period in our sowing window of late February to the end of April is 96 percent. “CliMate” can provide such estimates for most areas.

But if we needed 30mm for a successful establishment (heavy soil, little subsoil moisture) the odds of being able to sow in this slot drops to 61 percent. In other words we miss out on the chance of good winter feed from forage crops in more than one third of years.

Sub soil moisture important

Stored soil water is not only important for keeping crops growing during dry periods over autumn winter and spring but also maximises the probability of being able to establish them on time, a key consideration for reliable winter feed. If there is a good level of stored soil water at the required sowing time the probability of being able to sow on time increases dramatically.

Evidence from GRDC funded research notes that for every mm of stored soil moisture crop yields can increase by 15 -25 kg/ha. For grazing crops the gains are at least similar.

It is neither logical nor supported by research to sow crops directly into pastures without storing any soil moisture if reliable yields, grain or grazing, are aimed for. Even in lighter soils that can’t conserve great amounts of water that extra 40-100mm is commonly vital for early sowing as well as consistent good winter growth.

Direct drilling crops into active summer pastures, even poor ones where weeds generally replace pastures for water use, in addition to confronting little if any stored soil water, commonly face greater nitrogen deficiency. NSW DPI research notes differences of 40 kg/ha or more in available soil nitrogen where fallow weeds were not controlled in a timely manner.

Maximising stored soil moisture, as well as having moisture close to the surface as possible is dependent on efficient fallow capture and storage of rainfall. Early control of weeds over the fallow is critical, even if it means additional fallow sprays. It is not uncommon for example for us to spray our fallows five times over the fallow period.

Zero till and stubble retention part of the story

Reasonable levels of stubble cover (old pasture if coming from a pasture phase or crop residues in a cropping sequence) helps with fallow moisture capture as well as moisture storage closer to the surface. Zero till with stubble is generally more than helpful.

Narrow points and press wheels

Disc or narrow point plus press wheel seeders generally improves reliability of successful germination on a small rainfall event, while the ability to moisture seek with narrow points and press wheels greatly enhances the length of sowing window after larger rainfall events.

Variety choice critical

“Spring habit” winter cereal varieties (oats, wheat, barley triticale cereal rye) sown in February or March commonly came to head in May, June or July, with time dependent on sowing time variety and environment. These crops commonly recovered slowly and often poorly after grazing.

In contrast varieties with “winter habit” recovered far better after grazing, are less likely to be adversely affected by frost and retain high quality longer.

“Winter habit” is a characteristic where the growing point remains at ground level until a sufficient amount of cold weather triggers plants to change to “spring habit”, which means the head begins rising up the stem. Spring habit varieties have no such delay with heads growing up the stem as soon as tillering occurs.

When animals graze below the growing point, which can be quite early for spring habit types, the tiller dies and new tillers need to reform. Reforming of tillers can be slow, especially in the middle of winter and if soil water supply is low.

Varieties vary in their levels of “winter habit”. This means varieties with only low “winter habit” level will transfer to “spring habit” with heads growing up the stem after a shorter period of cold winter weather than varieties with high levels of “winter habit”. High levels of “winter habit” means heads remain at ground level for a much longer period in a given environment.

Desirable “winter habit” level is largely relates to climate and purpose. For example if the purpose is mainly for early sowing and for long grazing time over winter and spring a variety with a high level of “winter habit” may suit best.

A dual purpose role is more likely to best suit a variety with moderate to lower levels of “winter habit”. This allows early sowing with no running to head too early, nor loss of tillers, and a period of 30 to 100 days grazing prior to locking up for grain recovery. Desirable length of grazing is variable and is not only related to variety type but sowing time (more if early) and seasonal conditions.

Climate also has a big role in choosing how much “winter habit” a variety should have. Colder areas have “winter habit” satisfied faster, therefore varieties with greater “winter habit” are needed. In contrast in warmer environments varieties with less “winter habit” are needed, unless used only for grazing.

Varieties with “winter habit” tend to grow slower at first than “spring habit” types. This slower growth is more than often of little consequence if sowing earlier as the crop tends to make it up with better recovery post grazing in winter early spring.

Soil fertility

Nitrogen deficiency remains a more than common yield limiting factor in dual purpose crops.

A typical dual purpose cereal crop may provide 4.0 t/ha of drymatter for grazing and yield 4.0 t/ha of grain. The amount of nitrogen utilised in this example is typically 150 kg/ha for grazing and a further 84 kg/ha for grain, a total of 234 kg/ha.

While not a lot of the nitrogen needed for grazing is removed from the paddock in animal product, it takes time to be re-released to the soil via urine and faeces and the rotting back of trampled material. Nitrogen recycling is often also not distributed evenly across a paddock.

Figure 2. Urea at 100 kg/ha applied to oats mid-winter. In foreground no urea applied.

Treat sowing seed for rust and aphids

A major risk with early sowing of some cereal crops is barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV), a sometimes major disease threat to most varieties of oats, barley and wheat.

BYDV risk can be minimised by treating sowing seed with a registered insecticide to reduce risk of aphid attacks. Be aware that many insecticides have a grazing withholding period, commonly around nine weeks post sowing.

Rust can also be a greater risk in early sown crops, especially if autumns are humid. There are few resistant oat and barley varieties and popular winter habit wheats are commonly not that resistant to some rusts. Again seed treatment with an appropriate fungicide, or fungicide treated fertiliser applied with seed, can help reduce risk of early rust outbreaks.

Contact details

Robert Freebairn

Agricultural consultant

PO Box 316

Coonabarabran NSW 2357

Mb: 0428 752 149

Fx: 02 6842 5994

Email: robert.freebairn@bigpond.com