Fungicide management of mungbean powdery mildew

Author: Sue Thompson (1), Rod O’Connor (2,) Duncan Weier (2), Maurie Conway (3), Darren Aisthorpe (3), Max Quinlivan (3), Katy Carroll (3) and Peter Agius (3) | Date: 21 Jun 2016

1 Centre for Crop Health, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba Qld

2 DAFQ Regional Agronomy Initiative, Toowoomba Qld

3 DAFQ Regional Agronomy Initiative, Emerald Qld

Take home message

- Timely fungicide sprays are the key to effective management of mungbean powdery mildew

- The most practical time of the first fungicide application is at first sign of powdery mildew in the crop

- In most situations two sprays are better than one spray

- Incidence and severity will be determined by weather conditions – cooler humid conditions favour the disease

Background

Powdery mildew of mungbean is caused by the fungus Podosphaera fusca. In Australia, yield losses of up to 40% have been recorded in highly susceptible varieties such as cv. Berken. Plants are susceptible to powdery mildew from the seedling stage onwards, with the first sign of infection being small, circular, white powdery patches on the lower leaves. The disease can develop rapidly on individual leaves and also up mungbean plants; under the right weather conditions every leaf can be covered with the white powdery growth. Stems and pods may also be infected by the powdery mildew pathogen, resulting in discrete white patches. The visible white powdery growth consists of the spores (conidia) and spore-bearing structures (conidiophores)

Generally powdery mildews such as P. fusca need a living host for its’ survival from mungbean cropping season to season. Volunteer mungbean plants, phasey bean and perhaps other leguminous species are sources of infection. There is no evidence that the mungbean powdery mildew pathogen can survive on plant residues, in seed or in the soil. Infection of mungbean plants occurs when the spores produced in the white powdery patches become airborne, spread in the wind and land on leaves. There they germinate, infect the upper layers of the leaf (epidermis) and fine fungal strands (hyphae) grow across the leaf surfaces. The spore-bearing structures develop later on these fungal strands. A cycle of infection from spore germination to the production of the spore-bearing structures can take as little as 5 days. Disease outbreaks are generally favoured by mild temperatures and high humidity.

Management

Management of mungbean powdery mildew relies on the use of varieties with the highest possible levels of resistance and on the strategic application of fungicides. The variety Jade-AU has the highest level of resistance to P. fusca (moderately susceptible; MS), with all other Australian varieties apart from cv. Green Diamond being susceptible (S) or highly susceptible (HS). It is unlikely that significant gains in resistance to the powdery mildew pathogen will be made in the near future, so the targeted use of fungicides is vital to minimising the disease’s impact.

Fungicide trials

Four GRDC-funded trials were undertaken by USQ staff in collaboration with the DAFQ Regional Agronomy Initiative and Mungbean Improvement teams in 2015/16 to develop fungicide spray strategies for the control of powdery mildew on cv. Jade-AU. The trials were conducted in 2015 at Hermitage Research Facility, Warwick; HRF) and in 2016 at HRF, J Bjelke-Petersen Research Facility (= Kingaroy Research Facility; KRF) and Emerald Research Facility (ERF), with 6 treatments in the first year and 7 treatments in 2016 (Table 1). Spreader rows of cv. Berken were used in all trials.

The fungicide Folicur® 430 EC (active ingredient tebuconazole 430g ai/L) was applied at 145mL product/ha in >100L of water using hand-held boom sprayers. Fungicides containing tebuconazole are currently under APVMA permit (permit number 13979 – permit expires June 2017 and is only valid in Qld and NSW) for the control of mungbean powdery mildew.

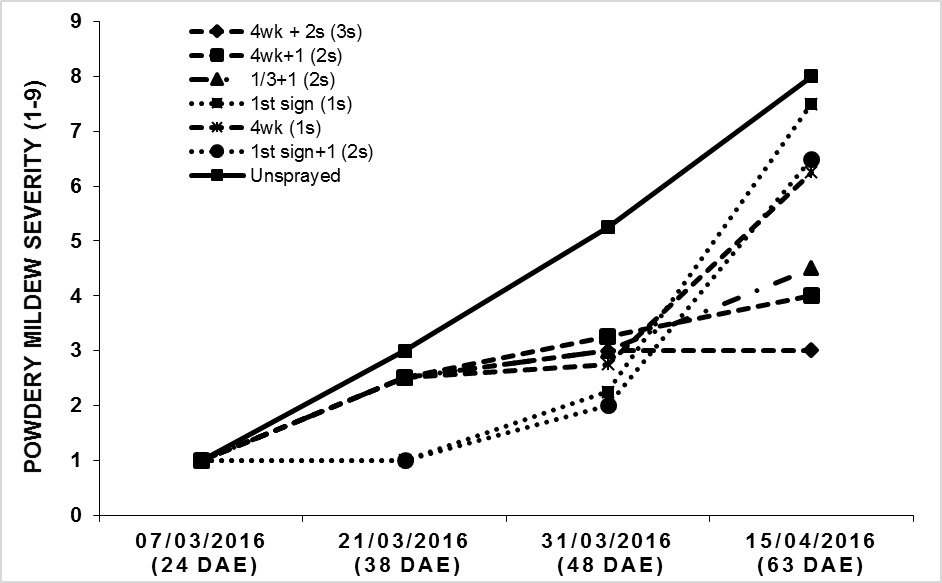

Trials were rated for powdery mildew severity at 3 dates using a 1-9 scale where 1 = no sign of powdery mildew and 9 = colonies of powdery mildew to top of 100% plants, with leaf drop. All plots were harvested at crop maturity. The results of the trials are present in Figure 1 and Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 1 displays the progression of powdery mildew in the 2016 trial at the Hermitage Research Facility. Powdery mildew developed rapidly in the unsprayed plots over the course of the trial, reaching a mean value of 8 at the last rating date (63 days after emergence (dae)). The two treatments involving a spray at the first sign of powdery mildew controlled the disease for at least 14 days, but then powdery mildew developed rapidly.

In all of the other fungicide treatments powdery mildew developed relatively slowly until 48 days after emergence, when it increased rapidly in the single 1st sign, 1st sign + 1 and the single 4 week spray treatments. On the last rating date, the 4wk + 2 spray, 4wk +1 spray and 1/3 +1 spray treatments had the lowest disease severities. Powdery mildew, as measured by the mean severity of the unsprayed treatment, was more severe at Hermitage (mean severity value of 8) and Kingaroy (8.3) than at Emerald (4.5).

Figure 1. Development of powdery mildew on mungbean cv. Jade-AU in the 2016 Hermitage Research Facility trial (the bar represents the LSD value at P=0.05)

In the 2015 trial at HRF the treatment which increased yield the most was the 3 spray treatment of the first spray 4/5 weeks after emergence (when there was no sign of powdery mildew in the plots) followed by 2 sprays, 14 days apart (9.5% increase) (Table 1). The second best treatment was the treatment involving a spray at the first sign of powdery mildew followed by 1 spray 14 days later (6.6%), and the next best was the treatment in which plants were sprayed when powdery mildew was 1/3 the way up plants followed by a spray 14 days later (3.3%). A single spray at the first sign of powdery mildew was not effective.

In the 2016 trials, the % increases in seed yield of the fungicide treatments over the unsprayed treatments ranged from -2.7% to +32.7% (Table 1). However, statistical analyses revealed that there were no significant differences in seed yield between any of the treatments (fungicide treatments and unsprayed treatment) at Kingaroy and Emerald and therefore the figures for % yield increase can only be used as a guide.

On the other hand, the trial at Hermitage was the only one in which differences in yield and therefore differences in % yield increase between treatments can be used with confidence. There, the yields of the four best treatments (first spray 4/5 weeks after emergence +1 spray or 2 sprays, first spray 1/3 up the plant + 1 spray, first sign of powdery mildew + 1 spray) did not differ significantly from each other and increased the seed yields by between 30.4% and 27.6%.

At Kingaroy there was a trend for three of these treatments (first spray 4/5 weeks after emergence +1 spray, first spray 1/3 up the plant + 1 spray, first sign of powdery mildew + 1 spray) to have the highest % yield increases, similar to the Hermitage trial. However, at Emerald there was no such trend, with the single spray treatments (first spray at the first sign of powdery mildew and first spray 4/5 weeks after emergence) having the highest % yield increases. These inconsistencies between sites could be due to low disease levels at Emerald (disease levels at Hermitage and Kingaroy were similarly high), and high variation in yield of treatments between replicate plots at Emerald and Kingaroy.

Table 1. Yield increases of mungbean cv. Jade-AU under different fungicide spray regimes in 2015 and 2016 trials at different localities

|

Treatment (total no. of sprays) |

% yield increase 1 |

|||

|

2015 |

2016 |

|||

|

HRF |

HRF |

KRF |

ERF |

|

|

4/5 weeks +1 spray 14 days later (2) |

- |

30.4* |

32.7 |

3.4 |

|

1/3 up plant + 1 spray 14 days later (2) |

3.3 |

28.8* |

19.2 |

-2.7 |

|

First sign + 1 spray 14 days later (2) |

6.6 |

28.7* |

18.2 |

0.5 |

|

4/5 weeks + 2 sprays 14 days apart (3) |

9.5 |

27.6* |

9.7 |

5.3 |

|

First spray 4/5 weeks after emergence (1) |

- |

22.6 |

30.6 |

8.1 |

|

First spray at first sign of PM (1) |

-3.3 |

17.9 |

14.5 |

14.9 |

|

First spray when PM is 1/3 up plant |

0.9 |

- |

- |

- |

1 % yield increase = (mean yield of treated plots – mean yield of unsprayed plots) x100 / mean yield of unsprayed plots

* the yields of these treatments were significantly greater than that of the unsprayed treatment; differences between these treatments were not significant

Differences in the performances of the treatments between years can be caused by differences in (i) weather factors, eg., temperature, humidity and rainfall, (ii) time of appearance of powdery mildew relative to plant age, and (iii) timing of sprays relative to appearance of powdery mildew. For example at Hermitage Research Facility in 2015 powdery mildew appeared late in the trial, with the first spray for the first sign of powdery mildew being applied 50 dae, the 4/5 weeks after emergence treatment being applied earlier (35 dae) and the 1/3 canopy treatment later (57 dae). By contrast, in the 2016 trial at HRF, powdery mildew appeared early, with the first spray for the first sign of powdery mildew being applied at 24 dae and the first sprays for the other two treatments both being applied at 34 dae.

Table 2 provides an example of the financial impact of applying fungicide sprays to manage powdery mildew on the cv. Jade AU. Based on the assumptions outlined in the footnotes of the Table and the yields of the treatments at Hermitage Research Facility, all of the fungicide treatments would have resulted in increased returns, the best 3 treatments being those with 2 sprays, irrespective of when the first spray was applied. The cost of the sprays far outweighed the returns, and this fact would also be true at lower yields and lower seed values.

Table 2. $ Returns of fungicide spray treatments in the 2016 Hermitage Research Facility mungbean powdery mildew trial

|

Treatment (total no. of sprays) |

$ gross return 1 |

$ net return 2 |

$ increase over unsprayed |

|

4/5 weeks +1 spray 14 days later (2) |

2057 |

2017 |

439* |

|

1/3 up plant + 1 spray 14 days later (2) |

2033 |

1993 |

415* |

|

First sign + 1 spray 14 days later (2) |

2030 |

1990 |

412* |

|

4/5 weeks + 2 sprays 14 days apart (3) |

2013 |

1953 |

375* |

|

First spray 4/5 weeks after emergence (1) |

1934 |

1914 |

336 |

|

First spray at first sign of PM (1) |

1861 |

1841 |

263 |

|

Unsprayed |

1578 |

1578 |

- |

1 Assumes $1000/t seed

2 Gross return – spray costs at $20/ha/spray

* the yields of these treatments were significantly greater than that of the unsprayed treatment; differences between these treatments were not significant

Researchers in the summer field crops pathology team at USQ are collaborating with plant disease epidemiology modellers at the Western Australia Department of Agriculture and Food (DAFWA) to develop a model, based on weather conditions, which predicts the first outbreak powdery mildew in a mungbean crop. This model will assist in determining the timing of the critical first fungicide spray.

Conclusions

- The fungicide tebuconazole is an effective fungicide for the management of powdery mildew on mungbean crops

- In general, the cost of applying a fungicide to control mungbean powdery mildew will be far outweighed by the resultant increase in yield

- The efficacy of different spray schedules varies from year to year depending on weather conditions which influence the time of appearance of powdery mildew in the crop and its subsequent development

- In most years, applying the first spray at the first sign of powdery mildew in a crop will be effective

- Application of a second fungicide spray, 14 days after the first, is highly recommended

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the input of Jo White (USQ) and David Laurence (DAFQ) for their assistance with setting up contracts and Mal Ryley (USQ Emeritus) for his advice and assistance with data tabulation.

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support.

The authors also thank staff at the DAFQ Research Facilities at Emerald, Kingaroy and Hermitage for their assistance.

Contact details

Sue Thompson

Centre for Crop Health, University of Southern Queensland

West St, Toowoomba Q

Mb: 0477 718 593

Email: sue.thompson@usq.edu.au

® Registered trademark

Varieties displaying this symbol beside them are protected under the Plant Breeders Rights Act 1994

GRDC Project Code: DAQ00186,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK