Emerging management tips for early sown winter wheats

Emerging management tips for early sown winter wheats

Take home messages

- Highest yields for winter wheats come from early to late April establishment.

- Highest yields of winter wheats sown early are similar to Scepter sown in its optimal window.

- Slower developing spring varieties are not suited to pre-April 20 sowing.

- Different winter wheats are required for different environments.

- Flowering time cannot be manipulated with sowing date in winter wheats such as spring wheat.

- 10mm of rainfall was needed for establishment on sands, 25mm on clays - more was not better.

Background

Winter wheat varieties allow wheat growers in the Southern Region to sow much earlier than currently practised, meaning a greater proportion of farm can be sown on time. The previous GRDC Early Sowing Project (2013-2016) highlighted the yield penalty from delayed sowing. Wheat yield declined at 35kg/ha for each day sowing was delayed beyond the end of the first week of May using a fast-developing spring variety.

Sowing earlier requires varieties that are slower developing. For sowing prior to April 20, winter varieties are required, particularly in regions of high frost risk. Winter wheats will not progress to flower until their vernalisation requirement is met (cold accumulation), whereas spring varieties will flower too early when sown early. The longer vegetative period of winter varieties also allows dual-purpose grazing.

The aim of this series of experiments is to determine which of the new generation of winter varieties have the best yield and adaptation in different environments and what is their optimal sowing window. Prior to the start of the project in 2017, the low to medium rainfall environments of SA and Victoria had little exposure to winter varieties, particularly at really early sowing dates (mid-March). Three different experiments have been conducted in the Southern Region in low to medium rainfall environments during 2017 and 2018, and one of these has been matched by collaborators in NSW for additional datasets presented in this paper.

Method

Experiment 1

Which wheat variety performs best in which environment and when should they be sown?

- Target sowing dates: 15 March, 1 April, 15 April and 1 May (10mm supplementary irrigation to ensure establishment).

- Locations: SA - Minnipa, Booleroo Centre, Loxton, Hart. Victoria - Mildura, Horsham, Birchip, Yarrawonga. NSW - Condobolin, Wongarbon, Wallendbeen.

- Up to 10 wheat varieties:- The new winter wheats differ in quality classification, development speed and disease rankings (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of winter varieties, including Wheat Australia quality classification and disease rankings based on the 2019 SA Crop Sowing Guide.

Variety | Release Year | Company | Development | Quality | Disease Rankings# | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Stripe Rust | Leaf Rust | Stem Rust | YLS | |||||

Kittyhawk | 2016 | LRPB | Mid winter | AH | MR | MR | R | MRMS |

Longsword | 2017 | AGT | Fast winter | Feed | RMR | MSS | MR | MRMS |

Illabo | 2018 | AGT | Mid-fast winter | AH/APH* | RMR | S | MRMS | MRMS |

DS Bennett | 2018 | Dow | Mid-slow winter | ASW | R | S | MRMS | MRMS |

ADV08.0008 | ? | Dow | Mid winter | ? | - | - | - | - |

ADV15.9001 | ? | Dow | Fast winter | ? | - | - | - | - |

LPB14-0392 | ? | LRPB | Very slow spring | ? | - | - | - | - |

Cutlass | 2015 | AGT | Mid spring | APW/AH* | MS | RMR | R | MSS |

Trojan | 2013 | LRPB | Mid-fast spring | APW | MR | MRMS | MRMS | MSS |

Scepter | 2015 | AGT | Fast spring | AH | MSS | MSS | MR | MRMS |

*SNSW only

AH=Australian Hard, APH=Australian Prime Hard, ASW=Australian Standard White, APW=Australian Premium White

R=resistant, MR=moderately resistant, MS=moderately susceptible

Experiment 2

How much stored soil water and breaking rain are required for successful establishment of early sown wheat without yield penalty?

- Sowing dates: 15 March, 1 April, 15 April and 1 May.

- Varieties: Longsword, Kittyhawk and DS Bennett.

- Irrigation: 10mm, 25mm and 50mm applied at sowing.

- Locations: SA - Loxton. Victoria Horsham, Birchip.

Experiment 3

What management factors other than sowing time are required to maximise yields of winter wheats?

- Sowing date: 15 April.

- Varieties: Longsword, Kittyhawk and DS Bennett.

- Management factors examined: Nitrogen (N) at sowing vs. N at early stem elongation, defoliation to simulate grazing, plant density 50 plants/m2 vs. plant density 150 plants/m2.

- Locations: SA - Loxton. Victoria - Yarrawonga.

Results and discussion

Experiment 1

Development speeds

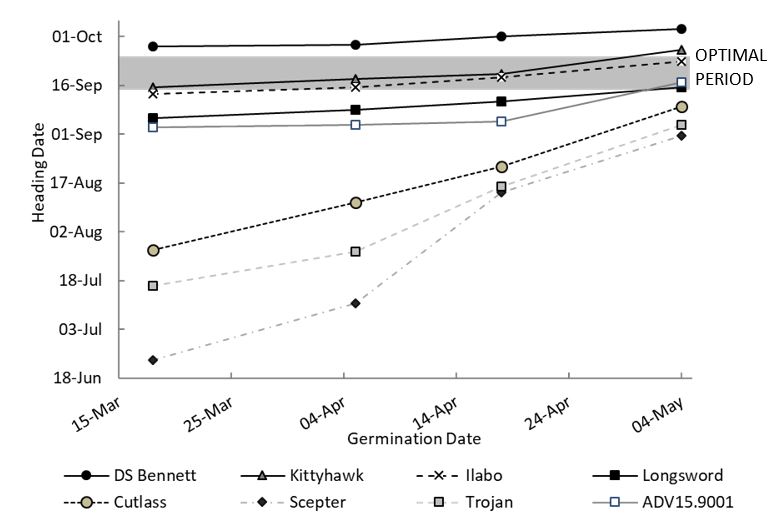

Flowering time is a key determinant of wheat yield. Winter varieties have stable flowering dates across a broad range of sowing dates. This has implications for variety choice as flowering time cannot be manipulated with sowing date in winter wheats like spring wheat. This means different winter varieties are required to target the different optimum flowering windows that exist in different environments. The flowering time difference between winter varieties is characterised based on their relative development speed into four broad groups — fast, mid-fast, mid and mid-slow for medium to low rainfall environments (Table 1 and Figure 1).

For example, at Hart in the Mid North of SA, each winter variety flowered within a period of 7-10 days across all sowing dates, whereas spring varieties were unstable and ranged in flowering dates over one month apart (Figure 1). In this Hart example, the mid developing winter wheats such as Illabo and Kittyhawk were best suited to achieve the optimum flowering period of September 15-25 for Hart. In other lower yielding environments such as Loxton, Minnipa and Mildura, the faster developing winter variety LongswordA was better suited to achieve flowering times required for the first 10 days in September.

Figure 1. Mean heading date responses from winter and spring varieties at Hart in 2017 and 2018 across all sowing times — grey box indicates the optimal period for heading at Hart.

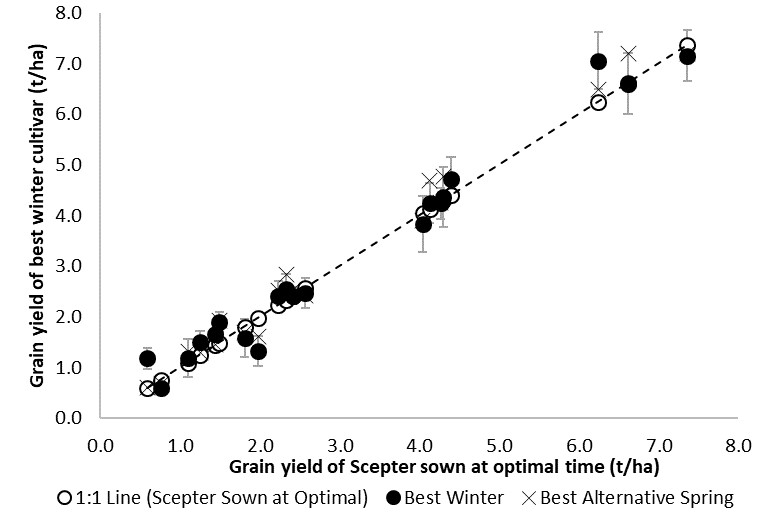

Winter versus spring wheat grain yield

- Across all experiments, the best performing winter wheat yielded similar to the fast developing spring variety Scepter sown at the optimal time (last few days of April or first few days of May, used as a best practice control) in 16 out of 20 sites, greater in three and less than in one environment (Figure 2).

- The best performing winter wheat yielded similar to the best performing slow developing spring variety (alternative development pattern) at 14 sites, greater at four and less than at two sites.

Figure 2. Grain yield performance of Scepter wheat sown at its optimal time (late April-early May) in 20 environments compared to the best performing winter wheat and best alternative spring wheat. Error bars indicate LSD (P<0.05).

Sowing time responses

- Across all environments, the highest yields for winter wheats generally came from early to late April establishment. The results suggested that yields may decline from sowing earlier than April and these dates may be too early to maximise winter wheat performance (Table 2).

- Slower developing spring wheats performed best from sowing dates after April 20, and yielded less than the best performing winter varieties when sown prior to April 20. This reiterates slow developing spring varieties are not suited to pre-April 20 sowing in low to medium frost prone environments.

Table 2. Summary of grain yield performance of the best performing winter and alternate spring variety in comparison to Scepter sown at the optimum time (late April-early May). Different letters within a site indicate significant differences in grain yield.

Site | Year | Scepter sown at optimum Grain Yield (t/ha) | Best Winter Performance | Best alternate Spring Performance | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Grain Yield (t/ha) | Variety | Germ Date | Grain Yield (t/ha) | Variety | Germ Date | ||||||||

Yarrawonga* | Vic | 2018 | 0.59 | a | 1.18 | b | DS Bennett | 16-Apr | 0.61 | a | Cutlass | 16-Apr | |

Booleroo | SA | 2018 | 0.77 | a | 0.59 | a | Longsword | 4-Apr | 0.69 | a | Trojan | 2-May | |

Loxton | SA | 2018 | 1.10 | a | 1.19 | a | Longsword | 19-Mar | 1.32 | a | Cutlass | 3-May | |

Minnipa | SA | 2018 | 1.25 | a | 1.50 | b | Longsword | 3-May | 1.29 | a | Trojan | 3-May | |

Mildura* | Vic | 2018 | 1.44 | a | 1.66 | b | DS Bennett | 1-May | 1.46 | a | LPB14-0293 | 1-May | |

Mildura | Vic | 2017 | 1.49 | a | 1.90 | b | Longsword | 13-Apr | 1.93 | b | Cutlass | 28-Apr | |

Horsham* | Vic | 2018 | 1.81 | a | 1.58 | a | DS Bennett | 6-Apr | 1.70 | a | Trojan | 2-May | |

Booleroo | SA | 2017 | 1.98 | a | 1.33 | b | DS Bennett | 4-May | 1.61 | b | Cutlass | 4-May | |

Minnipa | SA | 2017 | 2.23 | a | 2.42 | a | Longsword | 18-Apr | 2.52 | a | Cutlass | 5-May | |

Loxton | SA | 2017 | 2.33 | a | 2.55 | a | Longsword | 3-Apr | 2.83 | b | LPB14-0293 | 3-Apr | |

Hart | SA | 2018 | 2.41 | a | 2.42 | a | Illabo | 17-Apr | 2.52 | a | LPB14-0293 | 17-Apr | |

Rankins Springs | NSW | 2018 | 2.57 | a | 2.47 | a | DS Bennett | 19-Apr | 2.42 | a | Trojan | 7-May | |

Birchip | Vic | 2018 | 4.04 | a | 3.83 | a | Longsword | 30-Apr | 3.90 | a | Trojan | 30-Apr | |

Hart | SA | 2017 | 4.13 | a | 4.25 | a | Illabo | 18-Apr | 4.70 | b | LPB14-0293 | 18-Apr | |

Yarrawonga | Vic | 2017 | 4.27 | a | 4.24 | a | DS Bennett | 3-Apr | 4.26 | a | Cutlass | 26-Apr | |

Wongarbon | NSW | 2017 | 4.30 | a | 4.37 | a | DS Bennett | 28-Apr | 4.77 | a | Trojan | 13-Apr | |

Tarlee | SA | 2018 | 4.40 | a | 4.71 | a | Illabo | 17-Apr | 4.62 | a | LPB14-0293 | 17-Apr | |

Wallendbeen | NSW | 2017 | 6.24 | a | 7.05 | b | DS Bennett | 28-Mar | 6.49 | a | Cutlass | 1-May | |

Birchip | Vic | 2017 | 6.62 | a | 6.60 | a | DS Bennett | 15-Apr | 7.20 | a | Trojan | 15-Apr | |

Horsham | Vic | 2017 | 7.36 | a | 7.15 | a | DS Bennett | 16-Mar | 7.19 | a | Trojan | 28-Apr | |

*repeated frost during September followed by October rain.

Which winter variety performed best?

The best performing winter wheat varieties depended on yield environment, development speed and the severity and timing of frost (Table 2). The rules generally held up that winter varieties well-adjusted to a region yielded similar to Scepter sown in its optimal window. These results demonstrate that different winter wheats are required for different environments and there is genetic by yield environment interaction.

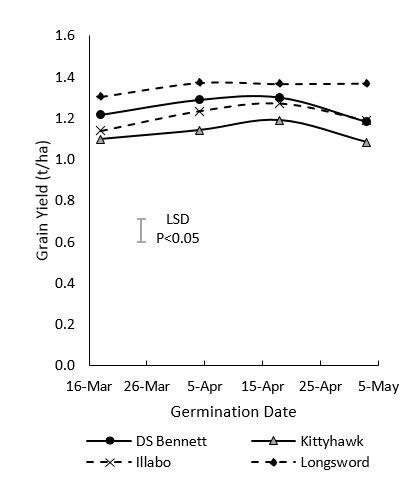

- In environments less than 2.5t/ha, the faster developing winter wheat Longsword was generally favoured (Table 2, Figure 3).

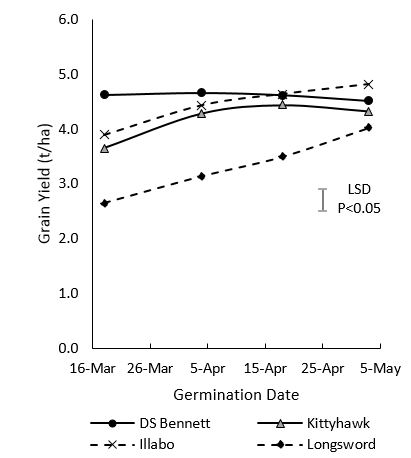

- In environments greater than 2.5t/ha the mid to slow developing varieties were favoured — Illabo in the Mid North of SA, and DS Bennett at the Victorian and NSW sites (Table 2, Figure 4).

The poor relative performance of Longsword in the higher yielding environments was explained by a combination of flowering too early and having inherently greater floret sterility than other varieties, irrespective of flowering date.

Sites defined by severe September frost and October rain included Yarrawonga, Mildura and Horsham in 2018. In these situations, the slow developing variety DS Bennett was the highest yielding winter wheat and had the least amount of frost induced sterility. The October rains also favoured this variety in 2018 and mitigated some of the typical yield loss from terminal drought. Nonetheless, the ability to yield well outside the optimal flowering period may be a useful strategy for extremely high frost prone areas for growers wanting to sow early.

Figure 3. Mean yield performance of winter wheat in yield environments less than 2.5t/ha (11 sites in SA/Victoria) | Figure 4. Mean yield performance of winter wheat in yield environments greater than 2.5t/ha (five sites in SA/Victoria) |

Experiment 2

2018 had one of the hottest and driest autumns on record and provided a good opportunity to test how much stored soil water and/or breaking rain is required to successfully establish winter wheats and carry them through until winter. The 10mm of irrigation applied at sowing in the sowing furrow was sufficient to establish crops and keep them alive (albeit highly water stressed in most cases) until rains finally came in late May or early June at seven of the eight sites at which Experiment 1 was conducted in 2018. The one exception was Horsham, which had very little stored soil water and a heavy, dark clay soil. At this site, plants that emerged following the first time of sowing in mid-March died after establishment and prior to the arrival of winter rains. Plants at all other times of sowing were able to survive. Experiment 2 was also located at this site, and 25mm of irrigation was sufficient to keep plants alive at the first time of sowing. A minimum value of 25mm for sowing in March on heavier soil types is supported by results from Minnipa in 2017, which also experienced a very dry autumn. In this case, approx. 30mm of combined irrigation, rainfall and stored soil water was sufficient to keep the first time of sowing alive. On lighter soil types, less water was needed and 10mm irrigation at sowing with 8mm of stored water plus an accumulated total of 13mm of rain until June allowed crops to survive on a sandy soil type at Loxton in 2018.

Based on these observations, it is concluded that when planting in March on clay soils, at least 25mm of rainfall and/or accessible soil water are required for successful establishment. Once sowing moves to April, only 10mm (or enough to germinate seed and allow plants to emerge) is sufficient.

Experiment 3

Yield responses to changes in plant density, N timing and defoliation have been small (Table 3). There have been limited interactions between management factors and varieties. The results from Experiments 1 and 3 confirm selecting the correct winter variety for the target environment and sowing winter varieties on time (before April 20) increase the chances of high yields. The target density of 50 plants/m² is sufficient to allow maximum yields to be achieved, and there is no yield benefit from having higher densities in winter varieties. Deferring N until stem elongation had a small positive benefit at Yarrawonga, and a negative effect at Loxton. Grazing typically has a small negative effect in all varieties, however the mean percentage grain yield recovery from grazing has been higher in Longsword (95%) compared to DS Bennett (87%) and Kittyhawk (82%), respectively.

Table 3. Mean main effects on grain yield (t/ha) from management factors at Loxton and Yarrawonga (2017 and 2018 = 4 sites)

Management Factor (Grain Yield t/ha) | Mean Management Effect (t/ha) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Variety choice | DS Bennett (2.21) & Kittyhawk | (2.10) | Vs. | Longsword | (2.40) | +0.30*** |

Seeding Rate (target density) | 150 Plants/m2 | (2.14) | Vs. | 50 Plants/m2 | (2.35) | +0.21*** |

Nitrogen Timing | Seedbed applied N | (2.32) | Vs. | N Delayed to Stem Elongation | (2.21) | -0.11 ns |

Grazing^ | Ungrazed | (2.38) | Vs. | Grazed | (2.11) | -0.27*** |

Sowing Date# | Early May Germination | (1.70) | Vs. | Mid-April Germination | (2.19) | +0.49*** |

^grazing was simulated by using mechanical defoliation at Z15 and Z30, # Sowing date effect derived from Experiment 1 at Loxton and Yarrawonga. Level of significance of main effect indicated by ns=not significant, *** = P<0.001.

Conclusion

Growers in the low to medium rainfall zones of the Southern Region now have winter wheat varieties that can be sown over the entire month of April and are capable of achieving similar yields to Scepter sown at its optimum time. However, grain quality of the best performing varieties leaves something to be desired (Longsword=feed, DS Bennett=ASW). Sowing some wheat area early allows a greater proportion of farm area to be sown on time. Growers will need to select winter wheats suited to their flowering environment (fast winter in low rainfall, mid and mid-slow winter in medium rainfall) and maximum yields are likely to come from early to mid-April planting dates. If planting in April, enough rainfall to allow germination and emergence will also be enough to keep plants alive until winter. If planting in March, at least 25mm is required on heavy soils. Reducing plant density from 150 to 50 plants/m² gives a small yield increase, while grazing tends to reduce yield slightly.

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC — the authors would like to thank them for their continued support. The project is led by La Trobe University in partnership with SARDI, Hart Field-Site Group, Moodie Agronomy, Birchip Cropping Group, Agriculture Victoria, FAR Australia and Mallee Sustainable Farming. Collaboration is with NSW DPI, Central West Farming Systems and AgGrow Agronomy & Research.

Contact details

Kenton Porker

SARDI

GPO Box 397, Adelaide SA 5001

0403617501

Kenton.porker@sa.gov.au

@kentonp_ag

James Hunt

La Trobe University – AgriBio Centre for AgriBiosciences

5 Ring Rd, Bundoora VIC 3086

0428 636 391

j.hunt@latrobe.edu.au

@agronomeiste

Felicity Harris

NSW DPI

Pine Gully Road, Wagga Wagga NSW 2650

0458 243 350

felicity.harris@dpi.nsw.gov.au

@FelicityHarris6

GRDC Project Code: 9175069,