The shifting landscape of human resource management in Australian agriculture

The shifting landscape of human resource management in Australian agriculture

Author: Sally Murfet (INSPIRE Ag) | Date: 20 Jun 2019

Take home messages

- To improve successful strategic human resources outcomes, agricultural employers need to:

- Understand future trends that will inform strategies about how to attract, retain and develop human capital.

- Acknowledge that the growth of the sector is dependent on recruiting smart, motivated and adaptive people; and

- Become an ‘industry of choice’ for current and potential employees.

Introduction

As a contemporary management discipline, strategic human resource management has increasingly attracted the interest of those who employ people in the agricultural sector, especially as it becomes more difficult to attract and retain an appropriately skilled workforce. As an agribusiness professional for more than twenty years, and someone who has worked in the human resource management space for the last five years, I have seen first-hand the significant difference it makes when business owners make the shift to strategic human resource management.

The business environment that farmers are currently operating in is different from that of previous decades. As larger industry players have acquired smaller farms, the sector has evolved from ‘Mum and Dad’ family businesses that have relied heavily on family labour, to be more dependent on labour outside the family unit. Additionally, in the past, agriculture has competed with the mining industry for skilled workers due to the close correlation of practical skills. However, the recent downturn in the mining sector has led to what the industry terms as the ‘Mining to Dining’ boom which has seen a decline in global demand for resources and an increase in demand for food. These trends place a greater emphasis on the agricultural industry to be more strategic with its human resource practices, to ensure it can attract and retain a workforce that has the right skills, knowledge and abilities to carry the industry forward. Keogh (June 2010) aptly says, ‘ensuring appropriate human resource development will be critical for the future growth, sustainability and global competitiveness of the Australian agriculture sector.’

Building agricultural sustainability and global competitiveness was a focus of the August 2018 Memorandum of Understanding between two agricultural peak bodies, National Farmers Federation and Agribusiness Australia, to collaborate to increase the farmgate value of the sector to $100 billion by 2030 according to Farm Online (2018). A $36 billion increase over the next 11 years is ambitious and places even more importance on ensuring that the industry has the skills and labour to achieve the required growth. In essence, strategic human resource management is the key to safeguarding the supply of skilled, motivated and engaged talent.

My entire professional life has been in the agricultural sector, either working on-farm or working for agribusiness companies. Throughout my career, I have observed that the management of employee(s) is generally weaved into everyday business practice rather than being a separate role within a business. The common misconception among agricultural employers is that strategic human resource management is only for corporate companies who have a dedicated department that deals with a workforce. They consider their business too small to worry about anything beyond the compliance of industrial relations aspect of employing staff.

A significant focus of my work over the last five years has been in the human resource management space. Firstly, managing a whole-of-industry skills, training and workforce development project for Tasmania’s state farming organisation, funded by the Tasmanian Government; and more recently, my own consultancy business. Through partnering with farmers, agribusinesses, industry bodies and government agencies to build capability and capacity in the sector’s human capital, I believe that a $100 billion national sector by 2030 is an achievable target as innovation and adaptability have traditionally underpinned Australian agriculture. However, unless the sector strengthens its approach to the management and development of its people, achieving that target is not a given. Strategic human resource management is a key tool to assist in future-proofing agricultural businesses to enable its employers to adapt and reshape for tomorrow's challenges.

What is human resource management?

Human resources management is defined by Watson (2010, cited in Armstrong 2017, p.5) as ‘the managerial utilisation of the efforts, knowledge, capabilities and committed behaviours which people contribute to an authoritatively co-ordinated human enterprise as part of an employment exchange (or more temporary contractual arrangement) to carry out work tasks in a way which enables the enterprise to continue into the future’.

Historically, human resource management has been carried out by ‘personnel managers’ or ‘personnel administrators’ according to Nankervis (2017, p.5). The primary functions undertaken by these early employment specialists during the industrial revolution and colonial period was recruitment, selection, training, salary administration, with a significant focus on compliance with employment law. The contemporary human resource profession has evolved from authoritative practices to strategic human resource management. A strategic approach to human resource management is much more inclusive and collaborative because it aligns the strategy of the business through policies and procedures to improve overall performance and build a culture that encourages innovation and competitive advantage.

Is there a difference between human resource management and strategic human resource management?

There is much confusion about the differences between human resource management and strategic human resource management. Nankervis (2017, p.13) describes human resource management as a systematic way to maximise the performance of employees through processes, such as recruitment, training, performance appraisal, remuneration, etc. By comparison, Armstrong (2014, p.16) says that strategic human resource management is an approach to the development and implementation of people strategies that are integrated with the vision, direction and goals of the business. The fundamental aim of strategic human resource management is to generate organisational capability by ensuring that a business has the skilled, engaged, committed and motivated employees it needs to remain sustainable and competitive. Simply put, strategic human resource management is a basic equation of strategy plus human resource management practices.

Why is strategic human resource management needed in agriculture?

The Australian farming workforce has changed considerably over recent decades. Mechanism, technology and scientific advancements have replaced some low-skill roles but have also created new ones. However, despite the technological advancement seen within the sector, Pratley (2012, as cited in the Australian Farm Journal, 2016) notes that there are upwards of five jobs for each graduate in the current market.

As a percentage, the sector accounts for approximately three per cent of the national workforce. Australian Bureau of Statistics (2015-16) notes that in Australia, 85,681 farms collectively employ 304,200 people. The workforce is comprised of 217,000 full-time workers and 87,200 part-time workers. While the sector is a significant employer and contributor to the national economy, particularly in rural and regional areas, workforce capacity and capability remain a significant issue for the industry.

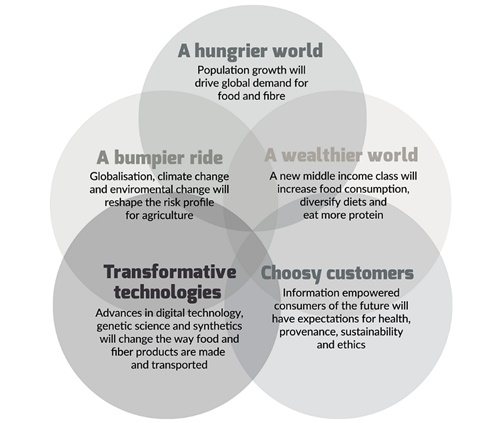

An essential aspect of strategic human resource management is understanding both the internal and external environment. In my experience, those farm businesses that take the time to understand both environments, and make adjustments accordingly, are the most successful enterprises. Armstrong (2017, p.36) considers that understanding the internal and external environment ensures that appropriate strategies, policies and practices are in place to support the business and its people to achieve the desired objectives. Furthering this, Nankervis (2013, p.11) says it is crucial that the person(s) responsible for human resources have a strong understanding of the business environment, industry challenges and opportunities, to appropriately inform initiatives that build human capability. Specifically looking at Australian farm businesses, Hajkowicz and Eady (2015) emphasise five key megatrends (Figure 1) that will significantly impact the future of the industry in the next fifteen to twenty years.

Figure 1. Megatrends impacting on Australian agriculture

Collectively, these trends will mean that the workforce of the agricultural sector will require new skill sets, a higher level of strategic thinking and a greater focus on human capital. Most strikingly, the first and the fourth trends will have potential impacts on strategic human resource management for the industry. Global population is expected to increase to nine billion by 2050, which means that food and fibre production will need to increase by 70-100 per cent over the next three decades to feed and clothe an additional two billion people. At the same time, advances in digital technology, genetic science and synthetics will change the way food and fibre products are made and transported (Hajkowicz & Eady, 2015). Change needs to be handled strategically and encompass the best and brightest people who can implement, navigate, grow and create the future that the industry needs to be competitive nationally and internationally. Put simply, people underpin the success of agriculture.

Thirty-three per cent of Australian farmers are self-employed (Table 1) and just over 70 per cent do not hire staff in their farming business (Table 2). With this in mind, it is essential to acknowledge that depending on size and scale, some farm businesses may have different human resource requirements. However, for those businesses that do employ, the challenges in attracting and retaining talent is placing more emphasis on the need for the industry to advance from human resource management to strategic human resource management in a bid to professionalise its practices.

Table 1. Australian farms by business structure June 2012 to June 2016.

Sole traders | Companies | Partnerships | Trusts | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

67,004 | 17,855 | 90,206 | 27,971 | 302,036 |

33% | 8.79% | 44.43% | 13.78% | 100% |

(Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016).

Table 2. Australian farms by employee 2016-17.

Non-employing | 1-19 | 20-199 | 200+ employees | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

71.20% | 27.73% | 0.98% | 0.04% | 100% |

106,945 | 41,654 | 1,469 | 55 | 150,212 |

(Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017).

Professionalising the practices of agricultural businesses in a strategic manner becomes even more critical when considering the three significant shifts that are likely to impact the industry over the next 2-5 years.

Shift 1: Labour and skills shortages

The availability and suitability of labour has been a concerning issue for the industry over a number of decades; however, it appears to have become more significant in recent years, for reasons such as automation and mechanisation, as outlined in the five megatrends mentioned previously. These factors add an extra layer of complexity to attracting skilled staff. The difficulty in finding staff, particularly at a management level, has been a consistent reason that many of my clients have not progressed with expansion plans.

Nettle (2015, p.17-18) says that much of the contemporary dialogue regarding Australia’s agricultural workforce, especially at a policy level, relates to workforce supply or skills shortages. Nettle considers that this focus is too limited and by only focusing on these two aspects, there is a risk that the industry’s human resource needs will not be adequately met.

There is little publicly available evidence that indicates specifically the number of people the Australian agriculture sector needs to attract to meet its workforce requirements. The Blueprint for Australian Agriculture 2013-2020 (facilitated by the National Farmer Federation), however, did provide a starting point. Despite almost reaching its maturity, the report indicated that the sector needed to find some 90,000 people in the short term to build the sector back to pre-drought levels. The report estimates that a further 15,000 people per annum are needed to replace the workforce exiting the industry.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016) indicates that approximately a third of farm businesses in Australia from 2012 to 2016 were operating as sole traders/individual and likely to have been run by family labour. The Australian Farm Journal (2015, p.18) says that family members remain an important part of the farm workforce; however, an increasing number of farms are relying on non-family employees to operate their enterprises. While it is common to hear anecdotal evidence of labour shortages, Keogh (2010) points out that there are current gaps in the statistical information collected by the Australian government which makes it difficult to accurately determine where the deficiencies are. Keogh says that the national agriculture and horticulture sectors would benefit from the government expanding the classifications and categories of the Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZIC) and Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZCO) to generate more meaningful data that will potentially inform strategic industry planning relating to skills and labour needs. An expansion of the classifications and categories will also assist the industry to understand human resource management strategies that will facilitate improved attraction and retention strategies; and make a valuable contribution to policy advice regarding the impacts of workforce supply and demand in Australian agriculture.

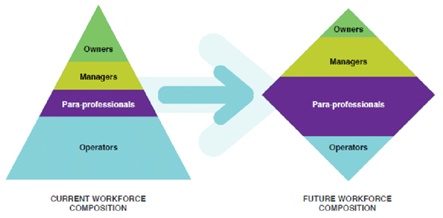

Shift 2: Workforce composition

The increased pace of change required by technology, globalisation, economic growth and customer demands is influencing the way agricultural employers attract, recruit and retain talent to the sector. These changes have resulted in notable developments to the types of characteristics and skills that farm businesses are aiming to recruit for, and the strategies required to keep older employees engaged for longer. An environmental scan conducted by AgriFood Skills Australia (2015) notes that the composition of the industry’s workforce is changing. The model (Figure 2) suggests that traditionally, agriculture has required a workforce that is heavily weighted to ‘operators’ (farm labour) but will transition to a diamond structure where the sector will see a greater demand for ‘para-professional’ and ‘manager’ roles. These roles will require more in-depth knowledge and higher-level skills in critical areas, such as water management and irrigation, sustainable practice, precision agriculture, animal performance, breeding, nutrition and people management. The Scan further indicates that to improve the competitiveness, profitability and sustainability of the industry, the sector needs to focus on five key areas:

- Building world-class business skills and risk management capability;

- Attracting smart, motivated and adaptive workers;

- Building higher level knowledge and skills within the existing workforce;

- Increasing enterprise’s ability to innovate, adapt to new technologies and apply research outcomes; and

- Retaining the best and brightest workers.

Figure 2. Structural changes predicted by Agrifood.

Shift 3: Demographics

The demographic challenge in Australian agriculture is complex and multi-dimensional. Understanding the demographic profile is an essential consideration for farmers to be more strategic with human resource management. Experts predict that Millennials (born 1981 and 1996) will form 50 per cent of the global workforce by 2020, paralleling this is the fact that Australian’s are living and working longer. Each scenario presents unique issues and challenges concerning the management and retention of a workforce. It is not uncommon for me to be working with clients who have four generations involved in their business. While there are many benefits of having a multi-generational workforce, some find it difficult to balance the needs, expectations, learning styles, communication preferences, leadership approach and values of each generation. Improving the understanding of the key generation drivers and motivators will benefit those businesses who wish to have an efficient, effective and inclusive workplace. Finding solutions to these challenges was the key motivation for pursuing a small project, as the recipient of the 2016 Runner-up Tasmania Rural Women of the Year, that looked at communication and generational drivers for farming businesses. It was evident that through an improved understanding of these drivers, the industry could strengthen their recruitment, attraction, retention and development strategies and potentially improve workforce participation and productivity that is needed to achieve the growth of the sector.

Demographic shifts are changing the landscape of Australian agriculture and are causing farm businesses to consider, or further develop, their human resource interventions more strategically. A shrinking workforce, a decline in the number of farms, and an increase in the average age of farmers are placing more pressure on farm businesses to ensure that they implement effective business systems. These systems are required to support industry employers to manage the entire human resource cycle.

Australian farmers are getting older – the average age of Australian farmers is 57 (Table 3). By comparison, the average age of employees nationally was 39.4 years according to Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016). This makes Australian farmers more than 17 years older than any other profession in the Australian economy. The Australian Social Trends report (2012), further highlights that almost a quarter (23%) of farmers were aged 65 years or over in 2011. Comparatively, the demographic aged 65 and over in other occupations is only three per cent. Australian Bureau of Statistics data also indicates that between the years of 1981 and 2011, the median age of farmers increased by nine years, while the median age of workers from other industries not associated with agriculture increased by only six years. During the corresponding period farmers aged 55 years and over increased from 26% to 47%; and farmers aged less than 35 years fell from 28% to just 13%.

Table 3. Australian farm management average age and average time in industry

Aust. | NSW | Vic. | Qld | SA | WA | Tas. | NT | ACT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Average age (years) | 57 | 58 | 58 | 57 | 55 | 56 | 56 | 52 | 57 |

Average time farming (years) | 37 | 37 | 36 | 38 | 35 | 36 | 35 | 26 | 30 |

(Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016-17).

Conclusion

Ignoring the people aspect of business strategy will be at the industry’s peril. Without a comprehensive awareness of the global trends that will shape agriculture in the short, medium and long term, finding talent with the right skills, knowledge and abilities to navigate the next wave of change will become extremely difficult and significant time and resources will be wasted.

While a $100 billion industry by 2050 is ambitious, it is achievable if agriculture strengthens its approach to the management of people through strategic human resource management. Ultimately, the aging workforce, including pending retirements and the potential impact of succession, may have significant implications for productivity if not addressed through the lens of this approach to people and business development.

Professionalisation is not simply vocational skilling; it is the genuine transformational change to a culture that values and integrates the platforms, processes, policy and people to achieve productivity, profit and social licence. This change is imminently required, and incremental change is not enough. Paradigms that have endured for generations need serious intellectual and practical rigour and robust business practices such as strategic human resource management are the tools of this transformation.

Strategic human resource management is not a magic bullet. However, in a candidate-driven market, without an understanding of future trends, the agricultural sector will be left behind. If agriculture is to innovate, adopt and adapt to future challenges, the requirement to professionalise is imperative if it is to be considered an industry of choice for current and future employees.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017). Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly, May 2017 Catalogue No. 6291.0.55.003.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016). Counts of Australian Businesses, including Entries and Exits, Jun 2012 to Jun 2016, cat. no. 8165.0.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2016-17). 7121.0 - Agricultural Commodities, Australia, 2016-17

AgriFutures Australia. (2015). Megatrends impacting Australian agriculture over the coming twenty years.

Australian Farm Institute. (2019). May 2016: Feature Article. [Accessed 27 January 2019].

Armstrong, M. (2017). Armstrong’s Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice – 13th edition

Keogh, M. (2010). Australian Farm Institute Ltd, Towards a Better Understanding of Current and Future Human Resource Needs of Australian Agriculture

Marshall, A (2018). ‘NFF and agribusiness lobby target $100b ag production agenda’. Farm Online, viewed December 2018.

Nankervis, A. (2015). Human Resource Management, 9th Edition. Cengage Learning AUS, 20160913. VitalBook file.

Nettle, R. (2015). More Than Workforce Shortages: How Farm Human Resources Management Strategies Will Shape Australia's Agricultural Future. Farm Policy Journal. 12(2) 17-27 (Winter quarter).

National Farmers Federation, Food, Fibre & Forestry Facts, 2017

Pratley, J (2016). 'Graduate supply for agriculture: a glimmer of hope', Agricultural Science, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 12-16.

Pratley, J (2015). Agricultural education and damn statistics: graduate employment and salaries. Agricultural Science, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 51–5.

Contact details

Sally Murfet

Inspire AG

sally@inspire-ag.com.au

0409 196 861