How does phenology influence yield responses in barley?

Author: Felicity Harris (NSW Department of Primary Industries), Hugh Kanaley (NSW Department of Primary Industries), David Burch (NSW Department of Primary Industries), Nick Moody (NSW Department of Primary Industries) and Kenton Porker (SARDI) | Date: 18 Feb 2020

Take home messages

- The optimal flowering period (OFP) to maximise grain yield potential and minimise effects of abiotic stresses in barley is earlier than for wheat and varies across growing environments

- Flowering time and grain yield is optimised with different variety x sowing date combinations, and varietal suitability varies across growing environments

- Relative frost risk of barley is lower than for wheat, and commercial barley varieties differ in frost tolerance.

Background

Maximum grain yield potential is achieved when crop development is synchronised with growing environment. Typically, barley is sown in a window from early–late autumn (April–May), to ensure flowering occurs at an optimal time in spring. This optimal flowering period (OFP) is defined early, by the risk of reproductive frost damage, and later, by high temperatures and terminal water stress during grain filling. Barley is considered to be more widely adapted, have superior frost tolerance, and has a yield advantage compared to wheat across environments of southern Australia (Harris et al., 2019), despite this, OFPs for barley have not been adequately defined which has implications for variety choice and sowing dates for growers.

Field experiments – Condobolin and Marrar, 2019

In 2019, field experiments were conducted at Condobolin and Marrar to investigate interactions between phenology, sowing date and growing environment. Cultivar responses were significantly influenced by seasonal conditions, with both sites recording below average growing season rainfall (April to October) and severe heat stress events which coincided with the late flowering to early grain filling period (Table 1).

Table 1. Growing season rainfall (GSR) April to October, frost and heat events at Condobolin and Marrar, 2019.

Site | GSR (mm)^ | Frost events (days <0°C) | Heat events (days >30°C) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Condobolin | 144 (246) | 5 | 9 |

|

Marrar | 194 (272) | 3 | 8 |

|

^Long term average (LTA) in parentheses

Phenology and yield responses to sowing date, 2019

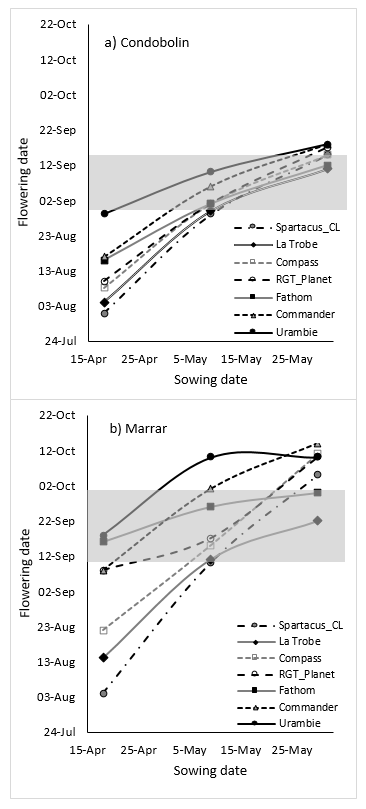

Variety and sowing date combinations which flowered in early-mid September at Condobolin, and in mid-late September at Marrar achieved the highest yields in 2019. This indicates that OFPs vary in timing and duration across different yield environments, as described for wheat (Flohr et al., 2017). As flowering time is a function of the interaction between variety, management and environment, the variety x sowing time combinations capable of achieving OFP and maximum grain yield also vary across environments (Figure 1). At both sites, optimal flowering time were achieved by fast winter type Urambie sown mid-late April, spring cultivars sown mid-May, and some faster finishing spring types (e.g. La Trobe and Fathom) capable of flowering within the optimal window when sown late-May. However in 2019, which was characterised by minimal frost risk, significant heat stress and terminal drought (Table 1), earlier flowering resulted in higher grain yields at both sites (Table 2).

b) Marrar field experiments in 2019. Shaded area indicates proposed optimal flowering period (OFP) at each location.

Table 2. Grain yield responses to sowing date for barley varieties at Condobolin and Marrar, 2019.

Variety | Condobolin | Marrar | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

18 April | 9 May | 1 June | 18 April | 9 May | 30 May | |

Banks (Mid spring) | 3.54 | 3.13 | 2.14 | 3.53 | 3.35 | 2.80 |

Biere (Fast spring) | 2.64 | 2.65 | 2.00 | 3.67 | 2.66 | 2.59 |

Cassiopée (French winter) | 1.59 | 1.17 | 0.79 | 1.80 | 1.64 | 1.17 |

Commander (Mid spring) | 3.73 | 2.35 | 1.86 | 3.62 | 3.00 | 2.43 |

Compass (Fast spring) | 4.00 | 2.99 | 2.56 | 3.96 | 3.09 | 3.03 |

Fathom (Mid-fast spring) | 3.80 | 3.07 | 2.54 | 4.57 | 3.58 | 3.00 |

La Trobe (Fast spring) | 4.05 | 2.90 | 2.54 | 4.28 | 3.42 | 2.69 |

RGT Planet (Mid-fast spring) | 4.02 | 2.38 | 1.90 | 3.07 | 2.87 | 2.60 |

Rosalind (Fast spring) | 3.54 | 2.71 | 2.93 | 4.06 | 3.76 | 3.07 |

Spartacus CL (Fast spring) | 3.64 | 3.44 | 2.42 | 4.06 | 3.95 | 2.97 |

Traveler (Slow spring) | 3.41 | 2.69 | 1.83 | 3.21 | 3.39 | 2.52 |

Urambie (Fast winter) | 3.49 | 2.41 | 1.96 | 3.54 | 2.74 | 2.51 |

Mean | 3.45 | 2.66 | 2.12 | 3.61 | 3.12 | 2.62 |

LSD (Variety) | 0.54 | 0.31 | ||||

LSD (SD) | 0.27 | 0.15 | ||||

LSD (Variety x SD) | 0.93 | 0.53 | ||||

How does barley optimal flowering period (OFP) compare to wheat?

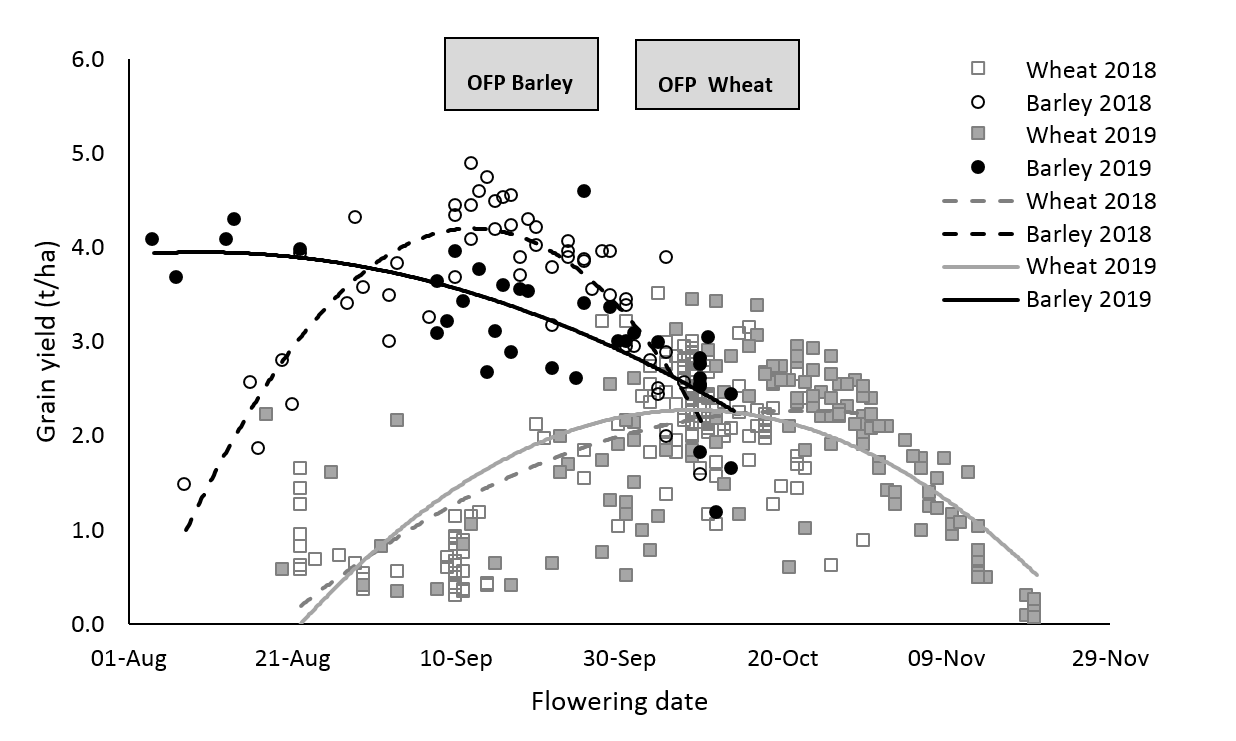

A preliminary comparison of co-located wheat and barley field experiments conducted in two contrasting seasons (Wagga Wagga, 2018 and Marrar, 2019) suggests that the OFP, whereby grain yield was maximised, for barley is significantly earlier, and relative frost risk lower than wheat, which has implications for variety choice in relation to sowing time for growers (Figure 2).

Cultivar adaptation to growing environment

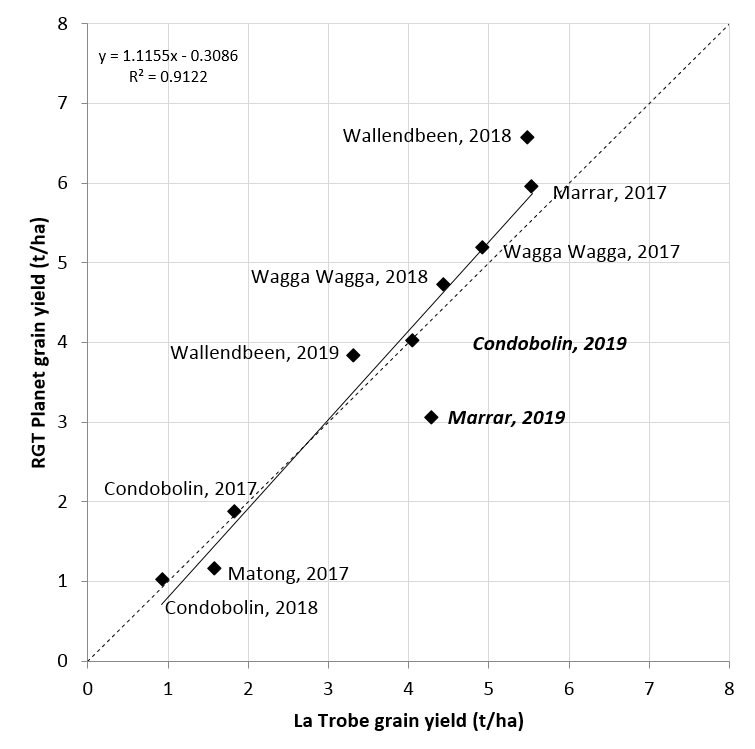

A comparative analysis between yields of RGT Planet and La Trobe from field experiments conducted at Condobolin (2017-19), Matong (2017), Wagga Wagga (2016-18), Marrar (2019) and Wallendbeen (2018-19) showed that these cultivars often achieved similar grain yields (Figure 3). Generally, in environments where grain yields were less than 2.5-3 t/ha, or in seasons such as 2019, with severe heat and terminal drought stress, La Trobe or faster finishing types were favoured; whilst when grain yields were greater than 2.5-3 t/ha, RGT Planet was capable of a yield advantage. Differences in comparable yields were also apparent in relation to management, whereby RGT Planet offers an opportunity for slightly earlier sowing (early May) compared to benchmark fast spring type La Trobe which is better suited to traditional mid-late May sowing dates.

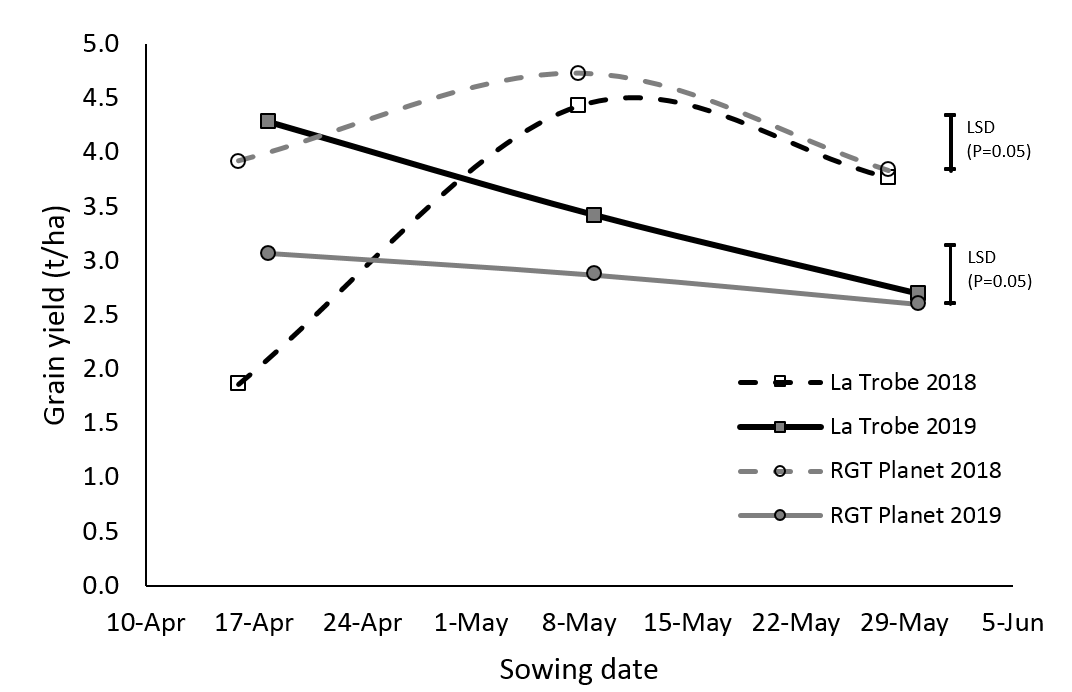

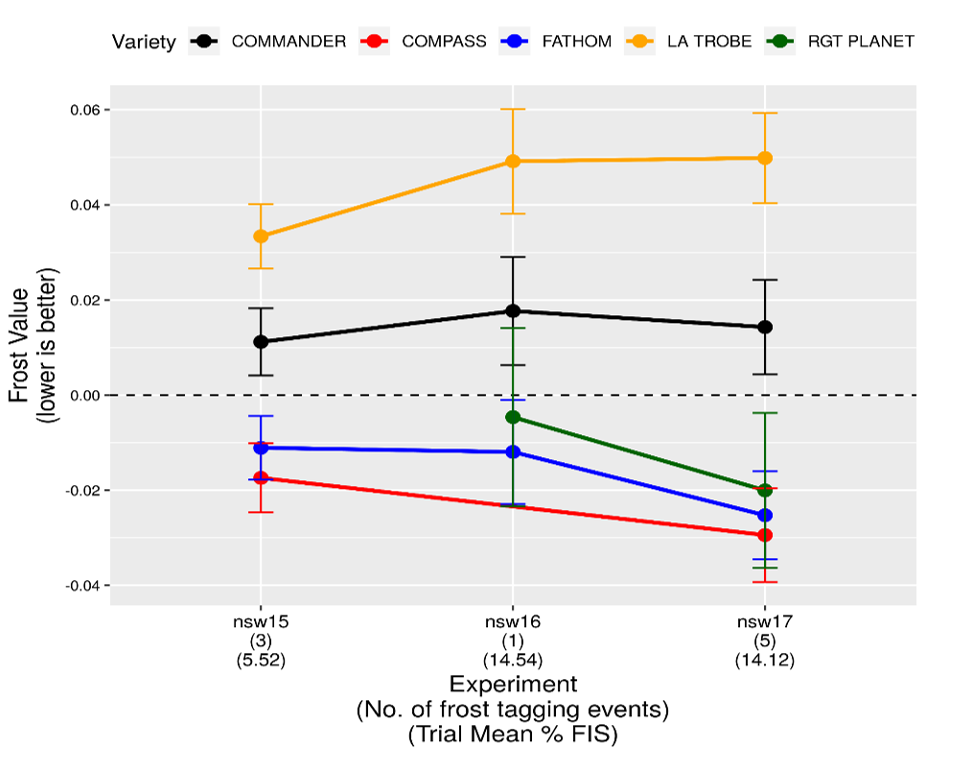

Varietal differences have been observed under high frost risk seasons, such as those experienced at Wagga Wagga in 2018, whereby RGT Planet was better able to maintain yield under frost conditions (SD1) compared to La Trobe (Figure 4). This aligns with the National Frost Initiative (NFI) barley variety rankings (Figure 5) which is a useful resource for both barley and wheat.

Source: https://www.nvtonline.com.au/frost/

Conclusion

Initial comparisons indicate that the optimal flowering time (OFP) for barley is earlier than for wheat, and timing and duration of barley OFPs varies with environment. Timing of flowering and grain yield is optimised with different variety x sowing date combinations, and variety responses and suitability differ across growing environments. Most spring barley varieties are still suited to traditional May sowing dates, however some longer season spring types such as RGT Planet offer opportunities for slightly earlier sowing (early May) compared with benchmark fast spring types such as La Trobe. Whilst early sowing options in frost prone environments of southern NSW are currently limited by suitable winter varieties, there are differences in relative frost susceptibility within current commercially available varieties in NSW.

Useful resources

https://www.nvtonline.com.au/frost/

References

Flohr, BM, Hunt, JR, Kirkegaard, JA, Evans, JR (2017) Water and temperature stress define the optimal flowering period for wheat in south-eastern Australia. Field Crops Research 209, 108-119.

Harris, F, Burch, D, Porker, K, Kanaley, H, Petty, H, Moody, N (2019). How did barley fare in a dry season? Presented at the GRDC Grains Research Update, Wagga Wagga, February 2019 .

Acknowledgements

Sincere thank you for the technical assistance of Cameron Copeland, Dean Maccallum, Mary Matthews, Jessica Simpson, Ian Menz, Bren Wilson and Javier Atayde at the Marrar site and Braden Donnelly and Daryl Reardon at the Condobolin site.

We also acknowledge the support and cooperation of the Pattison family at Marrar and NSW DPI at the Condobolin Agricultural Research and Advisory Station.

This research was a co-investment by GRDC and NSW DPI under the Grains Agronomy and Pathology Partnership (GAPP) project.

Contact details

Felicity Harris

NSW Department of Primary Industries, Wagga Wagga

Ph: 0458 243 350

Email: felicity.harris@dpi.nsw.gov.au

David Burch

NSW Department of Primary Industries, Condobolin

Ph: 0439 798 336

Email: david.burch@dpi.nsw.gov.au

Twitter: @NSWDPI_Agronomy

Varieties displaying this symbol beside them are protected under the Plant Breeders Rights Act 1994.

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK