Cereal disease update for 2024 where do we sit in the north

Cereal disease update for 2024 where do we sit in the north

Author: Steven Simpfendorfer (NSW DPI), Brad Baxter (NSW DPI) | Date: 23 Jul 2024

Take home messages

- Favourable planting and growing conditions so far are likely to be conducive to the development of wheat leaf diseases in 2024

- Correct identification is critical in disease management, with around 15% of cereal diagnostics submitted each season not related to disease

- The predominant leaf and head diseases in wheat in the last two seasons have been stripe rust, yellow spot and Fusarium head blight (FHB)

- These diseases are likely to also be prevalent across the region again in 2024

- Growers need to be proactive in their disease management plans and adapt to seasonal conditions

- In particular, FHB risk in 2024 is potentially high given the levels of Fusarium crown rot (FCR) in recent seasons, but risk will vary between individual paddocks and is heavily reliant on specific conditions (>36 h of above 80% humidity) occurring over a narrow window at flowering

- Assessing FCR levels (basal browning) around GS39 in wheat crops and inspecting retained sorghum and maize stubble for raised black fruiting structures (perithecia) is important to determine likely FHB risk in individual paddocks

- Prosaro® 420 SC foliar fungicide is registered for FHB control and must be applied at the start of flowering. Application by ground rig with twin angled nozzles and a high-water volume (minimum 100 L/ha) is recommended

- Help is available with disease identification and stay abreast of cereal disease management communications throughout the season, as 2024 is likely to be another dynamic year.

Introduction

If we all had a crystal ball, then this cropping game would be easy. So, what do we know from previous seasons with cereal diseases and what can we pre-emptively plan for and then proactively act on as required?

The contrast between leaf and head disease issues across the north in 2023 and 2022 was obviously stark. However, our memories of 2022 are fresh enough to have us nervous of cereal diseases in 2024 with the expectation of wetter spring conditions. This is particularly challenging in the north where fungicide supply issues often occur throughout the season and the so called ‘tap’ (rainfall) can turn off suddenly. What did we learn from the past two seasons and how can we use this to optimise management in 2024?

2022 – an exceptional season

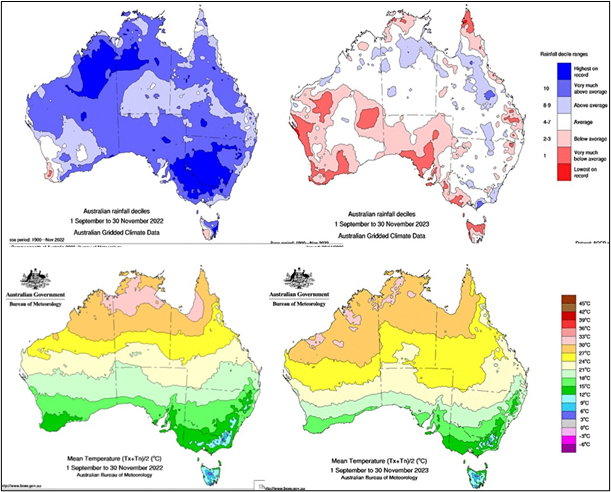

The 2022 season was wet! Records were broken and flooding was widespread in some areas. Spring rainfall (Sep–Nov) in 2022 was generally very much above average across northern NSW and southern NSW compared with average to below average in 2023 (Figure 1). Frequent rainfall is very conducive to the development of leaf diseases such as stripe rust, as causal pathogens require periods of leaf wetness or high humidity for spore germination and initial infection. However, just as significant a contributing factor to the prevalence of cereal leaf diseases was the spring (Sep–Nov) temperatures in 2022 which remained mild, compared with 2023 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Rainfall decile (top) and mean daily temperature (bottom) for spring (Sep–Nov) in 2022 (left) compared with 2023 (right). Source: Bureau of Meteorology (www.bom.gov.au).

Temperature interacts with cereal diseases in two ways. Each pathogen has an optimal temperature range for infection and disease development (Table 1). Time spent within this temperature range dictates the latent period (time from spore germination to appearance of visible symptoms) of each disease, which is also often referred to as the cycle time. Disease can still develop outside the optimum temperature range of a pathogen, but this extends the latent period. Hence, prolonged mild temperatures in 2022 were favourable to extended more rapid cycling of leaf diseases such as stripe rust, Septoria tritici blotch and wheat powdery mildew compared with 2023 (Figure 1).

Table 1. Optimum temperature range and latent period of common leaf and head diseases of wheat.

Disease | Optimum temperature range (°C) | Latent period (opt. temp) |

|---|---|---|

Stripe rust | 12–20 | 10–14 days |

Septoria tritici blotch | 15–20 | 21–28 days |

Wheat powdery mildew | 15–22 | 7 days |

Leaf rust | 15–25 | 7–10 days |

Yellow leaf spot | 15–28 | 4–7 days |

Fusarium head blight | 20–30 | 4–10 days |

The second effect that temperature can have on disease is more indirect, on the plants themselves. The expression of adult plant resistance (APR) genes to stripe rust can be delayed under lower temperatures. However, cooler temperatures also delay development (phenology) of wheat plants, extending the gap between critical growth stages for fungicide application in susceptible wheat varieties. The slower development under cooler spring temperatures therefore increases the time of exposure to leaf diseases in between fungicide applications, which is the case for stripe rust which is also on a rapid cycle time under these temperatures. Hence, underlying infections can be in their latent period and beyond the curative activity (~ ½ of cycle time with stripe rust) when foliar fungicides are applied. This can result in pustules appearing on leaves 5 or more days after fungicide application. The fungicide has not failed, rather the infection was already present but hidden within leaves and was too advanced at the time of application to be stopped by the limited curative activity of fungicides. At optimum temperatures, stripe rust has a 10-day cycle time in a susceptible (S) rated variety, whereas it is a 14-day cycle in a moderately resistant moderately susceptible (MRMS) variety. Disease cycles quicker in more susceptible varieties!

Reliance on fungicides for management makes susceptible (S) wheat varieties more reliant on correct timing of fungicide application. Frequent rainfall in 2022 caused plenty of logistical issues with timely foliar fungicide applications related to paddock accessibility by ground rig and/or delay in aerial applications. The associated yield penalty was significantly higher in more stripe rust susceptible varieties due to the shorter disease cycle time. There were plenty of reports of 10-day delays in fungicide applications around flag leaf emergence (GS39) due to uncontrollable logistics that saw considerable development of stripe rust, particularly in S varieties. Yield loss at harvest has been estimated at around 30–50% due to this 10-day delay. This simply does not happen in more resistant varieties, where there is more flexibility with in-crop management, because the disease is not on speed dial when climatic conditions are optimal. The recent 2022 season certainly challenged the risk vs reward of growing susceptible varieties – the management of which does not fit logistically within all growers’ systems.

Main leaf diseases in 2022 and 2023

How has the contrast in spring conditions in the last two seasons impacted the prevalence and levels of key cereal diseases across the northern region?

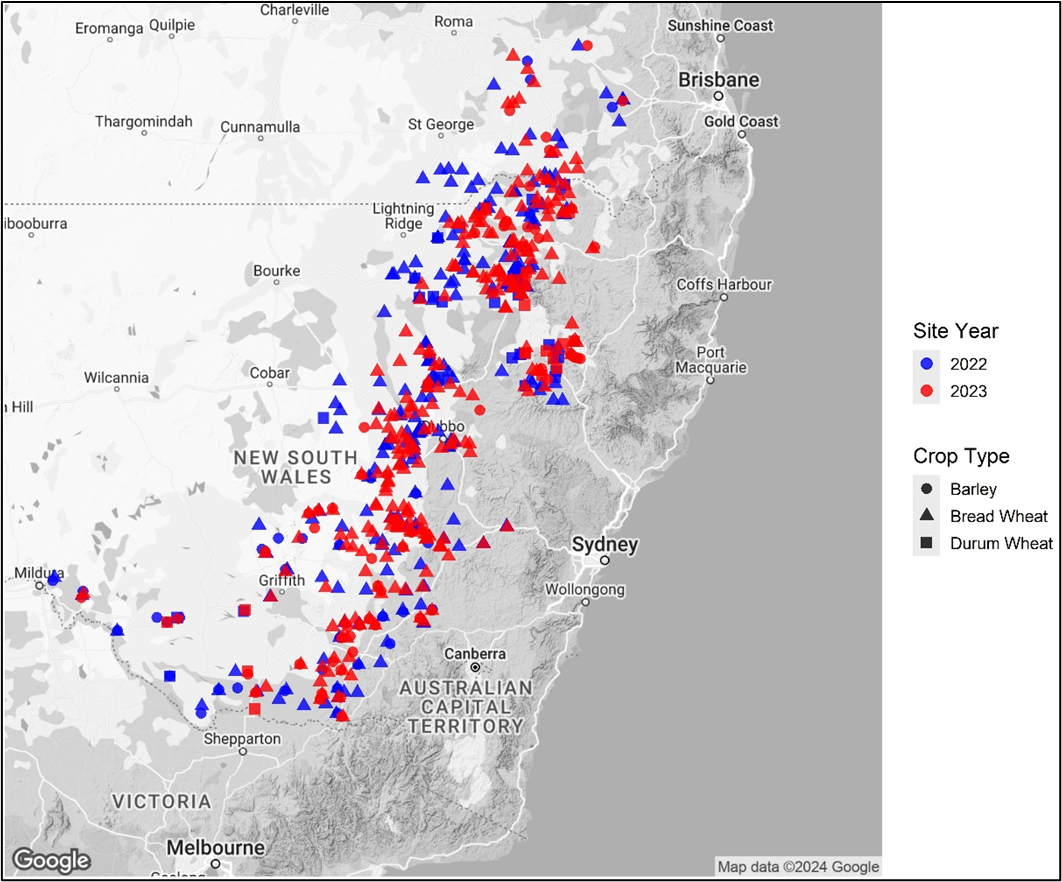

In collaboration with a range of locally based agronomists, random surveys of cereal crops across NSW were conducted annually with a total of 283 cereal crops surveyed in 2022 and 338 in 2023. This was composed of 468 bread wheat, 102 barley and 51 durum wheat crops (Figure 2).

Dried and ground tissue samples collected from each crop were assessed for the prevalence and levels of a range of cereal pathogens using quantitative PCR (qPCR) through the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI) molecular diagnostics laboratories. It is important to understand qPCR DNA assays are extremely sensitive with specificity to the target fungal pathogen of interest. Hence, we expect there to be high levels of pathogen found when infections occur. The approach used in this survey differs from traditional PREDICTA® B soil testing where calibrations have been developed to determine the relative risk of infection prior to sowing. Traditional PREDICTA® B tests quantify the amount of target pathogen DNA in the soil, old plant roots and stubble residues. This approach helps define the risk of infection developing within a season.

Figure 2. Location and cereal crop type surveyed across NSW in 2022 and 2023

Figure 2. Location and cereal crop type surveyed across NSW in 2022 and 2023

In this survey, plant samples were collected during grain filling and washed to remove soil and old stubble residues. Hence, the DNA tests in this context, determine the level of pathogen burden within either the base or top of the plant at a specified growth stage and do not measure contamination from previous crop residues. This represents actual infection levels of various pathogens within the actual crop plants during that season.

The key point being the DNA values presented in the following maps across seasons should not be compared with current PREDICTA® B pre-sowing risk levels or population densities for the different pathogens. Furthermore, the DNA values within plant tops or bases are generally presented on a log scale which indicates relative differences in pathogen loads within plants. This data is for comparative purposes only as the relationship between the actual quantity of different pathogen DNA in plant tissue and yield impacts has not been fully determined. However, increasing levels of pathogen DNA did relate to increased severity of visual disease symptoms in surveyed plant samples, e.g. crops with higher incidence and severity of basal browning had elevated Fusarium DNA levels. All data is presented as regional maps with colouring indicating the pathogen levels detected within plant tissue.

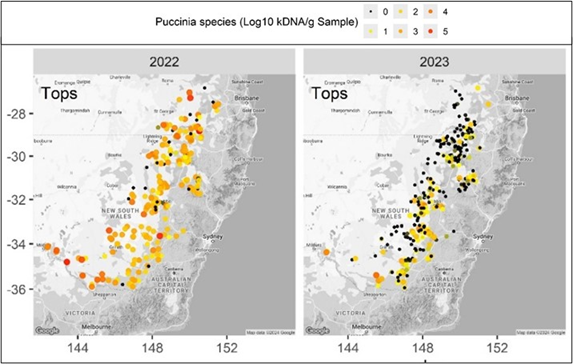

Puccinia spp. (cereal rusts, stripe rust)

A general qPCR test exists for the detection of the three wheat cereal rusts (stripe, leaf and stem) but cannot distinguish between species, and also detects barley and oat rust species. Fortunately, these rust species are easy to distinguish on visual assessments of collected random cereal samples. Hence, the Puccinia spp. maps over seasons predominantly (around 95%) relate to the detection of Puccinia striiformis (stripe rust) in wheat crops (Figure 3). The only other cereal rusts recorded within the surveys have been a low prevalence of Puccinia triticina (wheat leaf rust) and Puccinia hordei (barley leaf rust) in 2022.

The prolonged wet and mild conditions during grain filling in 2022 was favourable for continued stripe rust development in upper canopies and even resulted in head infections in some crops despite fungicide applications. Puccina spp. levels were noticeably higher in 2022 (Figure 3) where continued rainfall across much of NSW often prevented access to paddocks to apply fungicides by ground rigs or delayed application. This was further exacerbated by a shortage of aerial applicators. Drier and warmer spring conditions in 2023 markedly reduced the prevalence and levels of stripe rust infection in wheat crops across northern NSW and southern Qld (Figure 3). Arguably, difficulties with stripe rust management in more susceptible wheat varieties in 2022 also saw many of these dumped and/or a significant reduction in planting area to these varieties in 2023 in the north. Hopefully, the memory was still fresh enough from 2022 for growers not to venture back into these harder to manage varieties in 2024.

Figure 3. Quantification of Puccinia spp. (cereal rust) levels within plant tops of randomly surveyed cereal crops across NSW – 2022 and 2023.

Figure 3. Quantification of Puccinia spp. (cereal rust) levels within plant tops of randomly surveyed cereal crops across NSW – 2022 and 2023.

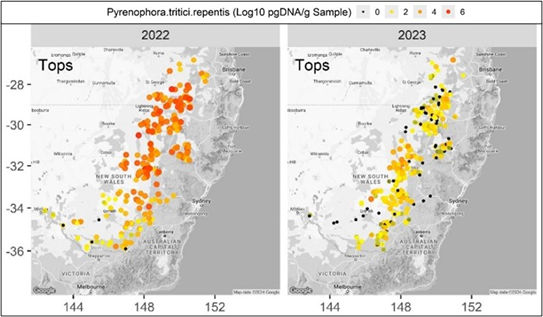

Pyrenophora tritici-repentis (yellow spot)

Yellow spot is a stubble-borne disease of durum and bread wheat caused by the fungus Pyrenophora tritici-repentis (Ptr). Wet weather favours infection and production of tan lesions with a yellow margin on the leaves of susceptible wheat varieties. Repeated rainfall events during the season are required for yellow spot infection to progress up the canopy of a wheat plant. Yellow spot has been reported to cause up to 30–40% yield loss in susceptible varieties under conducive conditions. Following generally dry conditions in 2019 the prevalence and levels of Ptr have progressively increased across NSW, especially in central and northern areas with consecutive wetter seasons in 2020, 2021 (data not shown) and 2022 (Figure 4). Ptr levels declined in 2023 with a drier seasonal finish restricting the severity of infection in the upper canopy.

Yellow spot infection can appear explosive when prolonged leaf wetness in wetter seasons such as 2022 favours repeat infection events. The high prevalence of Ptr in wheat crops across northern NSW and southern Qld in 2022 and 2023 indicates that there is elevated risk of yellow spot in wheat crops in 2024 in paddocks sown into retained stubble from these past two seasons. The yellow spot fungus releases spores (ascospores) off infected cereal stubble throughout the season so early fungicide application (<GS31) has little effect on inoculum loads later in the season.

Figure 4. Quantification of Pyrenophora tritici-repentis (yellow leaf spot) levels within plant tops of randomly surveyed cereal crops across NSW – 2022 and 2023

Figure 4. Quantification of Pyrenophora tritici-repentis (yellow leaf spot) levels within plant tops of randomly surveyed cereal crops across NSW – 2022 and 2023

Fungicide management in 2024

The 2022 season was the year for fungicides, especially in more susceptible varieties and with the mix of diseases that occurred. The prolonged mild conditions also extended the length of grain filling so there was a benefit from retaining green leaf area through this period in 2022. Remember, fungicides do NOT increase yield, they simply protect yield potential (i.e., stop disease from killing green leaf area). As highlighted above, disease is very dependent on individual seasonal conditions, so the same fungicide inputs were not required in 2023 with drier and warmer conditions being less conducive to cereal leaf diseases. What’s your disease management plan if spring returns to wetter and milder conditions? Seasonal outlook must be part of disease management planning. Early leaf disease pressure is likely to occur again in 2024, given elevated inoculum levels from 2022 and 2023 along with decent levels of stored soil moisture. Manage early leaf disease pressure in 2024 if present, then adapt management to spring conditions. The most effective fungicide can often be 2 to 3 weeks of warm and dry weather in spring.

No matter what your strategy there are a few fungicide basics that do not change.

- Fungicides do not fix environmental, herbicide, physiological or nutritional issues within crops. Correct identification is the first critical step in disease management with around 15% of cereal diagnostics submitted each season not related to disease, so fungicide application is unnecessary.

- Fungicides only protect leaves emerged at the time of application, they do not move into or protect leaves that emerge after application

- The top three leaves (flag, flag-1 and flag-2) are the main contributors to yield in cereal crops so fungicide strategies need to focus on maximising green leaf retention (that is minimising infection) in these structures

- All fungicides generally have much stronger protectant than curative activity, but this can vary between fungicide actives and pathogens (e.g. generally 1–2 days at best curative activity with yellow spot compared to 5–10 days with stripe rust)

- Length of protection depends on how quick each fungicide active moves through leaves (e.g. cyproconazole moves quickly so good rapid clean out of established stripe rust infections but more limited length of protection. Conversely, azoxystrobin much longer protectant but limited curative activity)

- Coverage is critical with foliar applications so higher water volumes are better and ground rig generally improved efficacy over aerial applications

- Fungicide resistance in fungal pathogens is real. Rotate and mix fungicide mode of action groups and actives within Group 3 (DMI, triazoles) between applications within a season

(AFREN | Australian Fungicide Resistance Extension Networks).

Fusarium head blight risk in 2024

The prevalence of Fusarium head blight (FHB) and white grain disorder (Eutiarosporella spp.) across large areas of eastern Australia in 2022 was unprecedented. However, what is the likelihood of these specific conditions (>36 h of above 80% humidity during flowering) occurring at a time-critical growth stage (early flowering) again in 2024?

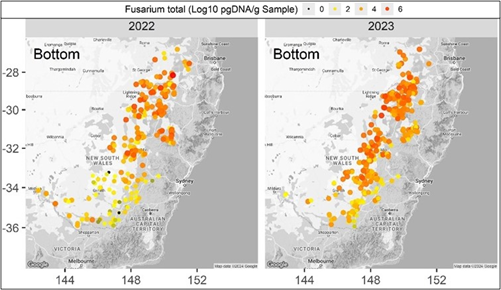

Fusarium crown rot (FCR) was widespread in 2022 and 2023 cereal crops and particularly elevated in more central and northern areas in 2023 (Figure 5). Testing of grower retained grain samples from the 2022 harvest showed that the dominant cause of FHB across eastern Australia in 2022 was related to tiller bases infected with FCR. That is, Fusarium infection of bread wheat, durum and barley crops in 2022 expressed as FHB due to wetter/milder conditions during flowering and grain fill (see Fusarium head blight and white grain issues in 2022 wheat and durum crops - GRDC).

Figure 5. Levels of Fusarium crown rot within plant bases of randomly surveyed winter cereal crops across NSW – 2022 and 2023

Figure 5. Levels of Fusarium crown rot within plant bases of randomly surveyed winter cereal crops across NSW – 2022 and 2023

Cause of FHB in 2022

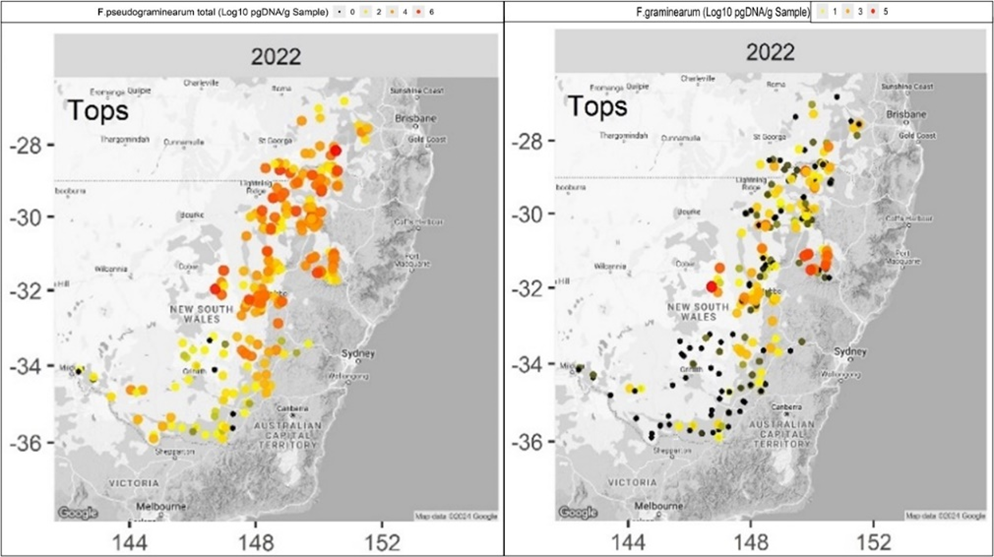

The main cause of FHB in 2022 was Fusarium pseudograminearum (Fp; maximum log10 of 6) with lower prevalence and levels of F. graminearum (Fg; maximum log10 of 5) in the tops of cereal plants from qPCR testing (Figure 6). These two species have different pathways for causing FHB with Fp reliant on basal FCR infections resulting in spore masses (macroconidia) being formed around lower nodes and rain splashed into heads during flowering. Hence, FHB risk when caused by Fp is closely linked to the levels of FCR within individual paddocks. Therefore, assessment of the extent of basal browning from FCR around flag leaf emergence (GS39) or earlier provides an indication of FHB risk from this species, if prolonged high humidity (i.e. rainfall) is predicted to occur during the subsequent flowering period of that crop.

Figure 6. Levels of Fusarium pseudograminearum (left) and F. graminarum (right) within plant tops of randomly surveyed winter cereal crops across NSW – 2022

Figure 6. Levels of Fusarium pseudograminearum (left) and F. graminarum (right) within plant tops of randomly surveyed winter cereal crops across NSW – 2022

In contrast, Fg can produce fruiting structures called perithecia on infected stubble, especially maize and sorghum but also winter cereals, which are raised black structures which release airborne smaller spores (ascospores). These ascospores can be spread in wind (up to ~100 m) to infect heads during flowering so inoculum levels in adjacent paddocks can also present FHB risk from Fg. Determining FHB risk from Fg therefore relies on visually inspecting retained maize, sorghum and winter cereal stubble again around GS39 for the formation of perithecia.

Managing FHB in-crop

Prosaro® 420 SC foliar fungicide (or combination of actives prothioconazole + tebuconazole) are registered for FHB control and need to be applied to protect the flowers at heading following label instructions. Research has shown that spraying at flowering (GS61) was more effective and had more yield benefit than spraying seven days before flowering. The anthers (flowers) are the primary infection site for FHB, so spraying before flowering provides reduced protection of these plant structures.

Overseas research has demonstrated the importance of spray coverage in FHB control, with twin nozzles (forward and backward facing) angled to cover both sides of a wheat head and high volumes of water (≥100 L/ha) being critical to efficacy. However, at best this still provides ~80% control. Aerial application gives poor coverage of heads and at best provides ~40 to 50% control. Some agronomists who used this application method in 2022 are questioning if the efficacy is even this high following their experience.

Prosaro® 420 SC is only usually applied to durum wheat (very susceptible to FHB) in parts of northern NSW which have dealt with FHB since 1999. Application to bread wheats has never previously been deemed economical but infection levels in many bread wheat crops in 2022 challenged this thinking. Note, in north America strobilurin fungicides (e.g. azoxystrobin) are not recommended from booting (GS45) onwards in paddocks with FHB risk as this can increase mycotoxin accumulation in infected grain (Chilvers et al., 2016).

Application timing is critical to fungicide protection but is also heavily dependent on predicted climatic conditions during flowering of prolonged high humidity above 80% for over 36 hours. That is, consecutive rain days not just total rainfall. This makes the application decision difficult as the product needs to be on hand without necessarily requiring application if dry conditions occur during flowering which prevents FHB infection. As a general rule, durum wheat is considerably more susceptible to FHB infection than bread wheats with barley having a lower risk again.

Summary

Cereal disease management is heavily dependent on climatic conditions between and within seasons. Therefore, the situation can be quite dynamic, including the unpredictable distribution of different stripe rust pathotypes across regions. Arm yourself with the best information available including the latest varietal disease resistance ratings.

FCR risk is high across much of the northern grain region. Widespread FHB in 2022 was predominantly the FCR fungus (Fp) letting you know that it does not go away with wetter and milder spring conditions. Do you know your FCR risk in paddocks sown to cereals in 2024, especially durum?

Keep abreast of in-season GRDC and NSW DPI communications which address the dynamics of cereal disease management throughout the 2024 season. Do not just focus on leaf diseases in 2024. Pull up a few plants randomly across paddocks when doing crop inspections and look for browning of the outer leaf sheathes and lower stems which is characteristic of FCR infection. This indicates your FCR risk if spring conditions are dry but also provides an indication of FHB risk if the 2024 spring is wet.

Further information

Australian Fungicide Resistance Extension Network (AFREN) - https://afren.com.au/

Chilvers M, Nagelkirk M, Tenuta A, Smith D, Wise K and Paul P (2016) Managing wheat leaf diseases and Fusarium head blight (head scab) - MSU Extension, Michigan State University, MSU Extension.

Simpfendorfer S & Baxter B (2023) Fusarium head blight and white grain issues in 2022 wheat and durum crops. GRDC Grains Research Update paper, accessed from https://grdc.com.au/resources-and-publications/grdc-update-papers/tab-content/grdc-update-papers/2023/02/fusarium-head-blight-and-white-grain-issues-in-2022-wheat-and-durum-crops

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers and their advisers through their support of the GRDC. The author would also like to acknowledge the ongoing support for northern pathology capacity by NSW DPI. Annual random crop disease surveys would not be possible without collaboration from participating growers and their agronomists which is greatly appreciated. Assistance from Dr Andrew Milgate (NSWDPI) with production of survey maps is also acknowledged.

Contact details

Steven Simpfendorfer

NSW DPI, 4 Marsden Park Rd, Tamworth, NSW 2340

Ph: 0439 581 672

Email: steven.simpfendorfer@dpi.nsw.gov.au

X (Twitter): @s_simpfendorfer or @NSWDPI_AGRONOMY

Date published

July 2024

® Registered trademark

GRDC Project Code: DPI2207-002RTX,