High-rate applications of chicken manure are showing positive signs of ameliorating sandy soils in trials on South Australia’s Yorke Peninsula.

Results from three years of trials indicate that applications combining deep ripping with surface applied nutrition – either fertiliser or chicken manure – are delivering the highest marginal returns, ranging from $934 per hectare to $1249/ha, cumulative over the three seasons. Marginal returns were calculated as the gross income minus amelioration and fertiliser costs, minus gross income of the no application treatment.

Depending on treatment cost, these delivered a return on investment ranging from 142 per cent to 521 per cent.

Agronomist Sam Trengove began the trials at Bute in 2015 with funding from SAGIT aiming to test long-term treatment options for the dune swale landscape of the northern Yorke Peninsula. Common constraints on these sands, which were all present at the trial site include low plant available water holding capacity, low organic matter, low nutrient availability, compaction, non-wetting and high risk for wind erosion .

In 2015 two trials were set up to test the following treatments:

Trial 1

- Deep ripping

- Annual fertiliser

- Clay (130 tonnes per hectare)

- Chicken litter – 0, 5 or 20t/ha

Deep ripping, clay and chicken litter were applied once only in 2015. Fertiliser treatments were applied annually.

Trial 2

- Placement of chicken litter or fertiliser, either on the surface or in subsoil at 30-40 cm deep

- Spading

- Matching the nutrition of 20t/ha chicken litter with 1,026 kilograms per hectare urea, 800kg/ha mono-ammonium phosphate, 420kg/ha sulphate of ammonia and 704kg/ha muriate of potash.

Agronomist Sam Trengove in a crop of lentils as a part of the sandy soil constraint trials he is conducting on the Yorke Peninsula, South Australia.

Sam Trengove, Agronomist

Agronomist Sam Trengove in a crop of lentils as a part of the sandy soil constraint trials he is conducting on the Yorke Peninsula, South Australia.

Seasonal responses

Season 2015 was a dry year for the region (decile 1 GSR = 204 millimetres). Grenade CL Plus wheat sown to the site responded dramatically to some of the treatments, particularly chicken litter and nitrogen fertiliser applications, according to Mr Trengove. Grain yields were generally below 2.0 t/ha.

“The treatments that grew the most biomass or had the biggest growth response were the treatments with chicken litter applied at 20t/ha, but these ran out of moisture at the end of the season,” he says.

“They tended to have poor grain quality and their yields were down a bit as well as a result of the dry season.”

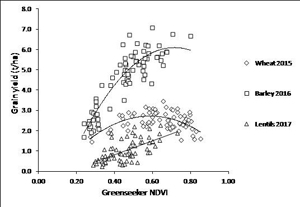

At the other end of the spectrum, there were treatments that had both low crop growth and low grain yield, and these were constrained mostly by low nutrition. There was an optimum in the middle that balanced crop biomass (as measured by NDVI) with soil moisture availability for optimised grain yield response, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1

Crop biomass from the trials was measured by Greenseeker NDVI at GS31 for wheat and barley and at early flower for lentils. The graph illustrates the relationship between crop growth and yield.

“The highest rate of 20t/ha of chicken litter was too much in this dry first season, but the 5t/ha treatment did quite well on its own, similar to what the standard fertiliser practice was producing, if not slightly better,” he says.

Season 2016 was a complete contrast to the previous year for the Spartacus CL barley sown to the site which performed much better than the wheat in 2015 (figure 1). It was a decile 9 growing season and decile 10 calendar year, equating to about 440 millimetres of growing season rainfall and double what was had the previous year. Barley yields approached 7.0 t/ha in the best treatments.

“Without much of a moisture limitation, nutrition was the biggest driving factor in 2016 and the highest rates of chicken litter gave us the best yields, whereas the year before, the dry finish curtailed yield responses,” Mr Trengove says.

“The 5t/ha manure treatment gave a yield increase of 0.83t/ha (35 per cent) compared with the untreated, but it wasn’t enough to take full advantage of the good moisture opportunity.

“The 5t/ha manure was good in year one but wasn’t enough in year two to push the higher yield potential, while the standard fertiliser applied in season which almost doubled yields compared to unfertilised treatments. The combination of standard fertiliser plus 5t/ha of chicken litter was better again (producing a 118 per cent yield increase), but neither of those were as good as the 20t/ha treatment (140 per cent increase).

“This highlights the amount of nutrition that is available in those high rates of chicken litter, maybe if we put more nitrogen in the fertiliser treatment the responses would have been more comparable.”

However, the litter could also have resulted in slow release and greater availability of nutrients to plants compared to inorganic fertiliser treatments, plus high application rates may have also improved the soil structure with long-term benefits in root growth and water uptake.

Season 2017 proved to be dry once again. Nonetheless, the PBA Jumbo2 lentils responded well to some treatments in the third growing season since application.

“The lentils were highly responsive to deep ripping and they also performed well in response to chicken litter treatments,” Mr Trengove says.

“The combination of the chicken litter and deep ripping treatments increased yields almost four-fold compared with untreated. However, the response to the fertiliser wasn’t there which was unexpected, so the question is, what were the lentils responding to in chicken litter that wasn’t supplied in the fertiliser?”

On-farm applications

Mr Trengove advises the application of chicken litter – whether it is through an annual application or in high rates for long-term benefits – should be based on site-specific needs. Sandy soils in particular with low inherent nutrition and low organic matter are more likely able to benefit than some other soils.

Nitrogen, phosphorus, sulphur and zinc are the most commonly applied nutrients in fertilisers, and analysis of the chicken litter (table 2) showed it was able to supply these in useful quantities. However, it also contains the full suite of essential plant nutrients, such as potassium, calcium, copper and boron, which are not typically not needed.

It is important to note that the analysis of chicken litter can vary significantly depending on animal husbandry practices at the time and tests from one source are not necessarily applicable to another.

Table 1. Nutrient concentration of applied chicken litter.| Nutrient | Nutrient conc. dry weight | Nutrient conc. fresh weight | Kg nutrient per tonne fresh weight |

|---|

| N Nitrogen | 3.8% | 3.5% | 35.0 |

| P Phosphorus | 1.72% | 1.58% | 15.8 |

| K Potassium | 2.31% | 2.13% | 21.3 |

| S Sulphur | 0.55% | 0.51% | 5.1 |

| Ca Calcium | 3.48% | 3.20% | 32.0 |

| Mg Magnesium | 0.73% | 0.67% | 6.7 |

| Zn Zinc | 0.46g/kg | 0.42g/kg | 0.4 |

| Mn Manganese | 0.51g/kg | 0.47g/kg | 0.5 |

| Cu Copper | 0.13g/kg | 0.12g/kg | 0.1 |

| B Boron | 0.05g/kg | 0.05g/kg | 0.05 |

| Fe Iron | 4.33g/kg | 3.98g/kg | 4.0 |

“If you’ve identified particular nutrient deficiencies that you know the chicken litter can supply then it might be an economic option,” he says.

“For example, if you have soils low in phosphorous and you have access to a chicken litter with reasonable phosphorous concentration then it’s a way of trying to increase those P levels without relying solely on inorganic fertilisers.”

At this site in cereals the main response has been to the nitrogen contained in the chicken litter.

According to Mr Trengove, results from these trials and anecdotal evidence in the industry has given farmers the confidence to test applications chicken litter on farm more widely. He says the results at this site show there is no need place the litter deep in the soil to take advantage of the nutritional benefits.

“The nutritional benefits of chicken litter which last at least three years is interesting,” he says.

“In this trial we weren’t able to compare the benefits of smaller annual applications of chicken litter versus a large once off application but we are looking for insights into placement in terms of surface or subsoil.

“In this case there was no real advantage of placing litter at depth and in one season the crops benefited more from applications on the surface.

“There has been other work to suggest putting organic matter in the subsoil will encourage roots to grow deeper and increase water use and yields, but we didn’t see that here.”

One-off soil treatments

One-off soil treatments such as chicken litter, clay and deep ripping are being tested for efficacy in long-term sandy soil amelioration.

Return on investment decisions

Mr Trengove says while there were clear soil nutrition benefits in applying chicken litter in the trials, cost and return on investment is always the main driver.

In the trials, the deep ripping treatment, either alone or combined with annual fertiliser or 5t/ha, chicken litter produced higher returns on investment (ROI). Deep ripping combined with 5t/ha litter produced the highest marginal return and ROI of 521 per cent.

Mr Trengove says there is still scope for improvement to this treatment by responding to seasonal rainfall and crop yield potential. In the decile 9 growing season of 2016, barley yield for this treatment increased by 2.25t/ha from additional fertiliser application.

According to Mr Trengove, the price for chicken litter has risen in response to increased demand in recent years. Other organic waste products (e.g. piggery wastes, biosolids) are expected to perform in a similar manner, depending on the nutrient concentration, so these are worth consideration.

Freight cost is another key factor given its low bulk density. Mr Trengove was able to source chicken litter from the Wakefield Plains at a rate of $36/t for product, freight and spreading. This equated to a cost $180/ha when applying 5t/ha.

“If you’re close to chicken sheds with access it can be economical but if you have to freight it over 100 kilometres, the economics are harder to justify,” he says.

“To use chicken litter on-farm you really need to go through the process of costing it out compared to more traditional fertiliser strategies.”

The annual artificial fertiliser costs were estimated at $430/ha over the three years including application costs for post-emergent applications.

He suggests using the ‘Organic By Product Value Calculator' developed by Rural Directions and RIRDC to assist with decision making. The calculator considers the nutrient content, nutrient values, freight and spreading costs to compare the value of using organic waste with the use of a traditional fertiliser source. This is available from the Rural Directions website.

Mr Trengove’s trials will be continued for another three seasons to 2020 as part of the GRDC sandy soil program in the southern region to evaluate the longevity of the treatment responses.

GRDC soils program

The GRDC has recently invested $9 million over five years into soil research aimed at developing strategies for overcoming two particular constraints in the southern region – sandy soils and poorly structured clay subsoils.

One of the projects, led by CSIRO senior research scientist Dr Lynne Macdonald, will run until 2021 and is looking at cost effective approaches to overcome constraints to poor crop water use in sandy soils. Trials have been established to investigate both low cost, annual, strategies (mitigation) and higher cost soil treatments that increase crop growth and yield over multiple seasons through application of organic matter, clay and/or mineral fertilisers (amelioration).

The research partners behind the GRDC investment include the CSIRO, the University of South Australia, Primary Industries and Regions South Australia, Mallee Sustainable Farming, and Ag Grow Agronomy.

The research program has established new trial sites across South Australia, Victoria and New South Wales as well as continuing monitoring of sites established by previous projects where there is the opportunity to learn about the likely longevity of treatment effects. While still in early stages, preliminary 2017 results are consistent with work from 2014 at Karoonda where yield gains of about 1t/ha were achieved from physical interventions such as spading and deep ripping.

GRDC Research Code: CSP00203, TRE00002

More information

Dr Lynne Macdonald,

08 8273 8111,

lynne.macdonald@csiro.au

Sam Trengove

samtrenny34@hotmail.com

0428 262 057

@TrengoveSam

Useful resources

GRDC Update paper – Amelioration of sandy soils – opportunities for long term improvement

GRDC Ground Cover – Push to lift sandy soils potential

'Organic By Product Value Calculator' developed by Rural Directions and RIRDC

GRDC Project Code: CSP1606-008RMX, TRE00002,