Paddock Practices: Practical remedies to target challenges of deep ripped soils

Paddock Practices: Practical remedies to target challenges of deep ripped soils

Date: 18 Sep 2020

Key points

- Deep ripping sandy soils provides average yield increases of 0.6 tonnes per hectare where it breaks up a naturally consolidated layer usually 30 centimetres or more below the surface.

- Deep ripping is presenting operational challenges for growers such as excessive sowing depth and erosion which are being addressed in new research.

- Practical changes to operations, such as sowing at reduced speeds or lifting the front tynes, can help remedy issues created by soft deep ripped soil.

- Rolling deep ripped soils can provide useful benefits without affecting the subsurface layer broken up by the ripping process.

Some growers experience poor crop establishment after sowing into deep ripped sandy soils, and press wheel design, steel drum rollers and different deep ripper and seeder tyne configurations are being investigated as possible solutions.

These remedies are among a range of management options that have been employed by growers who have experienced challenges after deep ripping, and research is quantifying the benefits of each approach.

Mallee Sustainable Farming consultant Michael Moodie is leading efforts to validate some of these options and recently outlined this work at the GRDC’s Sea Lake Grains Research Update.

“There are clear benefits to deep ripping and many growers have made it a part of their system, but some are coming across operational challenges in terms of sowing the crop after ripping,” he said.

Results from the GRDC investment, ‘Increasing production on sandy soils in the low-medium rainfall areas of the southern region’, has shown opportunities for average yield increases of 0.6 tonnes per hectare when hard subsoils are deep ripped.

The GRDC Deep Ripping Fact Sheet states that the sandy soils of the low-rainfall Mallee regions of South Australia and Victoria are commonly affected by a consolidated sub-surface layer, in addition to non-wetting, poor fertility or acidity constraints. While the consolidation occurs naturally at about 30 centimetres or more below the surface on many sandy soils, this is exacerbated by compaction from machinery traffic.

The hard layer inhibits root growth and the uptake of water and nutrients from deep soil layers especially during grain filling. Strategic deep ripping can dramatically improve the productivity of these soils by breaking up the consolidated layer and enabling roots to make use of previously unused water and nutrients at depth.

However, the soft nature of the deep ripped sands can impede trafficability of machinery and impair the establishing crop, including:

- Excessive seed depth caused by furrow slumping due to deeper rows when machinery sinks into the softened soil surface (poor trafficability)

- Excessive soil throw from rear tynes into furrows of the front tynes

- Pre-emergent herbicide damage from thrown topsoil

- Soil erosion

On-farm experience

Victorian grower Alistair Murdoch has implemented a deep ripping strategy as a part of his operation in the past two seasons.

He was encouraged to try deep ripping after observing positive yield responses in a trial on his property in 2018. This trial was a part of a GRDC investment managed by the Australian Controlled-Traffic Association and the Department of Primary Industries and Regions research division, the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI). In this trial, wheat yields on the unripped soil were 0.8t/ha, while the wheat sown into ripped soil returned 1.68t/ha yields.

Mr Murdoch said the sandy soils and his low rainfall environment at Kooloonong presented the typical challenges for productivity, and the consolidated soil layer beneath the surface was clearly hindering root growth and water access by his crops.

“The initial responses to deep ripping were impressive without any major issues, so this encouraged us to expand to other paddocks.”

Mr Murdoch said each year he is learning better ways to rip and manage the paddocks after ripping.

Practice change solutions

Mr Moodie said there were a number of avenues growers could explore to address the “perils of ripping sandy soils”, some being more involved than others.

“Some options to address these issues are straightforward, such as reducing tractor speed when sowing deep ripped paddocks,” he said.

“This will reduce the amount of soil throw from the rear tynes into the furrows of the front tynes as the seeder moves along, and potential exposure to pre-emergent herbicides.

However, Mr Moodie said if herbicide damage was the main issue, then changing to post-emergent herbicides was also an option.

“Growers could look to avoid the problem where they can by not using pre-emergent herbicides or pulling back on rates,” he said.

“Pulse crops are particularly at risk of herbicide damage from soil throw so this needs to be carefully managed.”

Mr Moodie said significant wind erosion and furrow collapse were hard to manage, but if possible, sowing early under warm temperatures promotes rapid crop emergence which helps protect the soil.

“We’re currently looking at quantifying the benefits of other practices including ripping at an angle to seeding direction, implementing a controlled or semi-controlled traffic situation where important wheel tracks are left un-ripped, and the use of stubble strip barriers,” he said.

Similar soil amelioration challenges have been experienced in Western Australia, and Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development researcher Bindi Isbister recently summarised some lessons at the Perth Grains Research Update 2020. She discussed grower experiences and practice changes employed on WA properties to reduce these risks.

Rolling after ripping

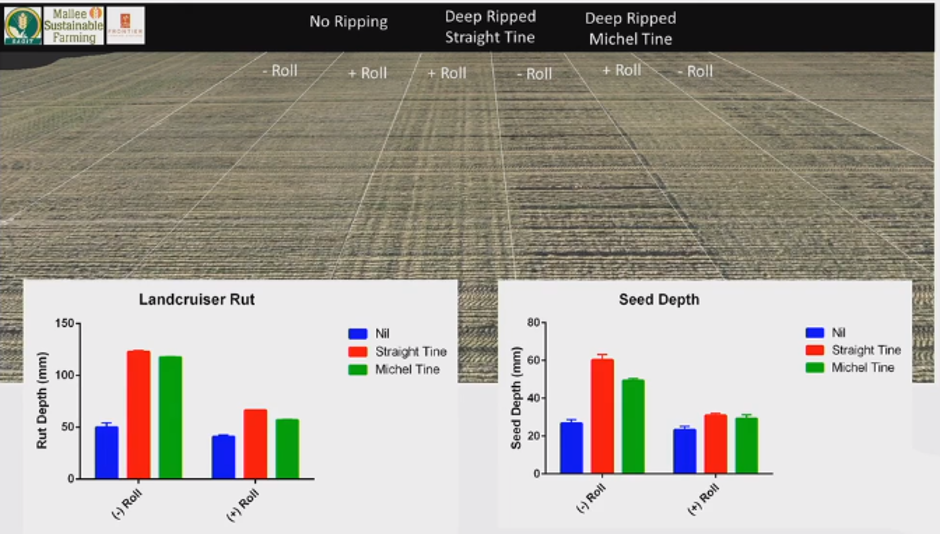

The use of rollers to consolidate the surface of a deep ripped paddock is the focus of one of Mr Moodie’s new experiments this year at Pinnaroo, funded by the South Australian Grain Industry Trust (SAGIT).

The impact of rolling the soil with a steel drum roller after deep ripping, on soil throw, seeding depth and wind erosion has been tested this year.

Mr Moodie said this tactic was looking promising, but yield data from this season will help confirm initial observations.

“The rolling treatment in the trial limited the sowing depth issues pretty effectively,” he said.

“By deep ripping and then rolling, you reconsolidate that surface layer so the seeder doesn’t sink as deep.”

Mr Moodie said the rolling procedure can be conducted so that it only consolidates the top 5-10cm of soil without cancelling the benefits of the ripping deeper in the profile.

“The consolidated layer that limits crop root growth, water use and yield on sandy soils occurs much deeper in the profile,” he said.

Tyne position

While reducing tractor speeds during sowing will decrease soil throw, this will cause problems for many growers with large sowing programs. Mr Moodie said tyne depth could also be altered to help address this issue.

“We know that neighbouring tynes throw soil into the adjacent furrow, so we’re trying to quantify that under different seeder set-ups,” he said.

Reducing the depth of the front tyne on parallelogram seeding bars could limit soil throw and seed depth as the seeder sinks into ripped areas of the paddock.

Mr Moodie’s investigations in deep ripped paddocks have so far shown a 16 per cent decrease in wheat establishment and reduced early vigour as a result of excess soil throw from the rear tynes into the furrows of the front tynes. In some cases, seed in the furrows sown by the front tynes was 30 millimetres or deeper.

Grower lessons

Mr Murdoch believes a new air seeder acquired this year has addressed several of the issues that are commonly challenging growers who implement deep ripping practices.

His new parallelogram seeder uses a RootBoot design which places seed in the shoulder of the furrow. This is in contrast to his previous system where seeds were placed at the bottom of the row using knife points.

They also use a PackMaster™ drill control function which detects light and heavy soil types, and uses variable downforce pressure to ensure uniform depth of seed placement.

“While it wasn’t our initial intention when we swapped seeding systems, our new seeder avoided the problem of our seeds being buried by furrow collapse or soil throw,” Mr Murdoch said.

Mr Murdoch reflected on expanding their ripping program and erosion risk.

“We encounter numerous soil types within our dune/swale landscape and while we have chosen to deep rip our sandy soils, the unknown for me is where to stop deep ripping,” he said.

“By talking with our agronomist and reviewing normalised difference vegetation index images, we’re thinking we should be deep ripping a lot more soil types across the property.

“A local farmer who deep ripped his whole paddock this season rather than targeting the sandy sections, has had really positive responses as far as we can see on the NDVI images, including the loamy swales.

“My biggest concern has been soil erosion caused by big wind events after seeding and the subsequent poor emergence of buried seed.

“But, surprisingly, we didn’t strike any problems after experiencing strong winds this year.

“A few dry years had resulted in some bare soils around seeding and this was definitely one of the biggest risks for our system, but I think our seed placement with RootBoot tynes has been helpful.”

More information

Michael Moodie, Frontier Farming Systems

0448 612 892

michael@frontierfarming.com.au

Useful resources

GRDC Project Code: CSP1606-008RMX,