Pulse update 2022 – maximising pulse production in the low rainfall zone

Pulse update 2022 – maximising pulse production in the low rainfall zone

Author: Sarah Day, Penny Roberts (Sardi Agronomy Clare, University of Adelaide) | Date: 26 Jul 2022

Take home messages

- Consider variety selection each season to match phenology to environment or agronomic practice.

- Consider higher yielding non-herbicide tolerant pulse varieties where herbicide residues are not an issue and good weed control can be achieved prior to or at sowing.

- It is important to follow an integrated disease management approach, select varieties with improved disease resistance, monitor pulse crops for disease infection and apply foliar fungicides at the first sign of disease prior to rain.

- Herbicide choice and application timing is important with lentil crops, particularly as lentil is extremely sensitive to Group 5 herbicide use in dry conditions.

Background

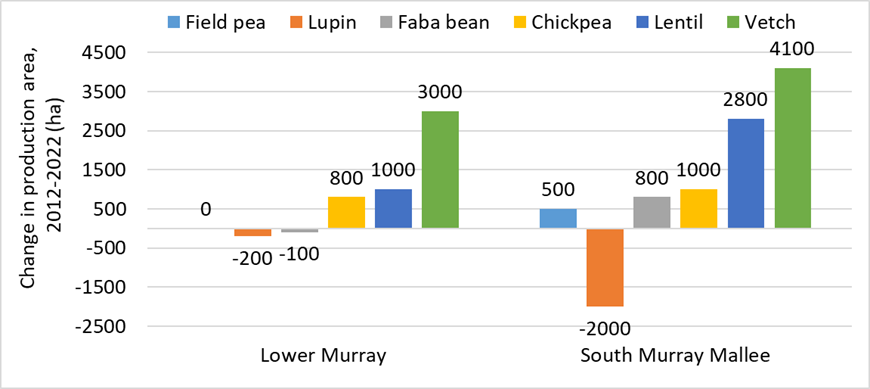

Pulse production has expanded in the low rainfall zone over the last decade, with a shift in the areas planted to specific pulse crop types over this timeframe (Figure 1). Lentil, chickpea and vetch production have expanded in the Lower Murray and South Murray Mallee regions since 2012, while field pea and faba bean production have remained more stable and lupin production has fallen. High grain prices have driven the expansion in some pulse crops, such as lentil and chickpea. These crops are now being considered as cash crops rather than being utilised solely for their break crop benefits.

Whilst growers in low rainfall regions have increased their production area to pulses, the challenges of identifying and adopting best management strategies for resource and economic efficiency, and maximising production, remain. This paper describes the outcomes from previous and current pulse research, focusing on matching variety to environment, herbicide use and disease management.

Figure 1. Change in the production area (ha) of pulse crops over the last decade (2012–2022) in the lower Murray and South Murray Mallee regions in South Australia. Source: PIRSA Crop Estimates, 2012 and 2022.

Matching phenology to environment

Lentil

There are many lentil variety options currently available to growers, with more being considered for commercial release in coming seasons. These offer a range of phenology characteristics, herbicide tolerance, disease resistance, and environmental adaptation. PBA Hallmark XT and PBA Bolt have improved tolerance to boron and salt over other lentil varieties, and have shown improved adaptation in low rainfall environments (Day et al. 2019). PBA Bolt offers early to mid-flowering and maturity, lodging resistance, improved boron and salt tolerance, and high grain yield in low-rainfall years and environments. However, PBA Bolt does not offer any herbicide tolerance characteristics, and post-emergent weed control options are limited. PBA Hallmark XT, a cross between PBA Bolt and the first commercial herbicide tolerance lentil (PBA Herald XT), combines improved salt and boron tolerance with herbicide tolerance. PBA Hallmark XT would be well suited to areas or seasons where Group B herbicide residues are an issue or where early season post-emergent weed control options are required. PBA Jumbo2 lentil remains the highest yielding red lentil in South Australia and is a good fit where soil residues, post-emergent weed control or soil constraints are not limiting lentil production. PBA Highland XT is a medium sized red lentil with improved herbicide tolerance and is showing adaptation to drier lentil-growing regions of the Victorian Mallee and South Australia.

Faba bean

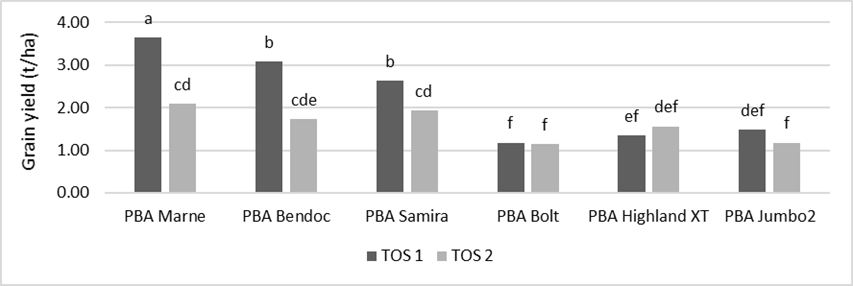

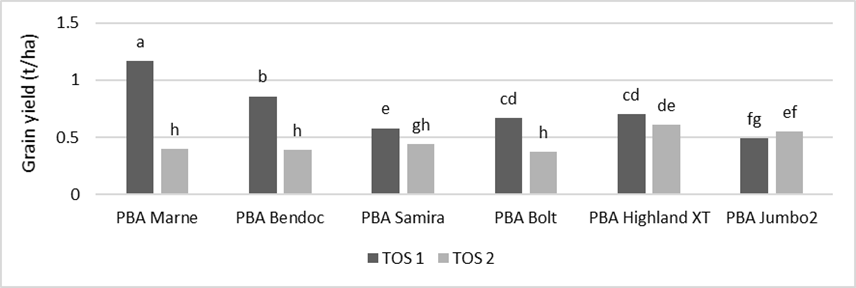

There is benefits of early sowing for faba bean in the medium to low rainfall zones, providing that there is an early season break or adequate soil moisture for early crop establishment (Roberts et al. 2019, Bruce et al. 2021, Day et al. 2021). An average grain yield advantage of 68% was achieved where faba bean was sown and established in early April compared to early May across South Australia in 2020 (Figures 2 and 3). However, selecting faba bean varieties to match time of sowing is important. The greatest yield response was seen in PBA Marne, a variety adapted to low rainfall, short growing seasons and early sowing opportunities. In contrast, the popular mid-flowering variety PBA Samira has shown greater yield stability across all times of sowing (Roberts et al. 2019), with no or a small yield advantage from early sowing this variety. However, early sowing can come with its own set of challenges, including post-emergent weed control, particularly if a successful knockdown herbicide application is not achieved pre-sowing. PBA Bendoc can provide early season post-emergent weed control options that are not available in other varieties, due to its improved herbicide tolerance characteristics.

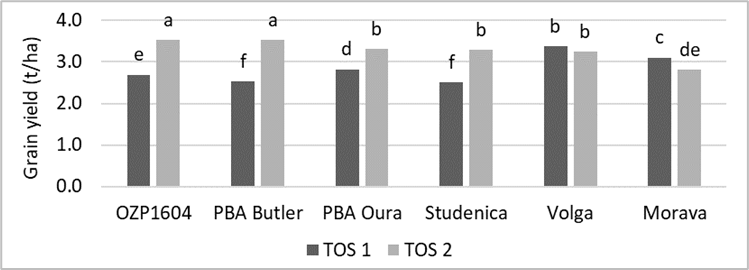

Figure 2. Grain yield (t/ha) of faba bean and lentil varieties sown over two times of sowing (ToS 1 = 2 April, ToS 2 = 6 May) at Tooligie, 2020. Bars labelled with the same letters are not significantly different (P<0.05). 10mm of supplementary irrigation was provided via dripper irrigation in-furrow immediately post -April sowing and pre-May sowing within a couple of days to simulate a singular rainfall event.

Figure 3. Grain yield (t/ha) of faba bean and lentil varieties sown over two times of sowing (ToS 1 = 31 March, ToS 2 = 7 May) at Wudinna, 2020. Bars labelled with the same letters are not significantly different (P<0.05). 10mm of supplementary irrigation was provided via dripper irrigation in-furrow immediately post-April sowing and pre-May sowing within a couple of days to simulate a singular rainfall event.

Field pea

Conventional field pea varieties offer high biomass production potential and are well suited to alternative end-uses to grain production. However, conventional varieties have not offered improved biomass production over semi-leafless varieties in low rainfall environments (Day et al. 2019). PBA Butler is a high yielding semi-leafless variety with improved resistance to bacterial blight that has performed particularly well across low rainfall environments (Day et al. 2019). New field pea variety releases may have improved adaptation and production in these environments compared to the current varieties, but as for lentil, evaluation has so far been limited. For example, PBA Taylor is a high yielding, widely adapted field pea variety with virus resistance that has shown good adaptation and production in low rainfall environments in preliminary trials.

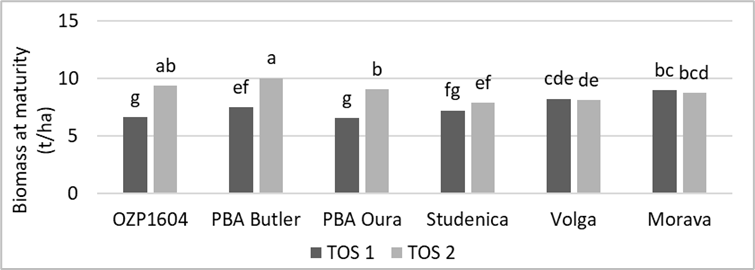

To maximise production, avoid sowing field pea too early (Figures 4 and 5). Sowing field pea too early can increase the exposure to blackspot spores over a longer period and increase vegetative growth, leading to increased risk of leaf disease, higher yield loss from disease infection, and increased risk of crop lodging prior to harvest. Sowing early can also expose flowers and early pods to cold and frost risks. At Eudunda in 2020, where early sowing reduced field pea grain yield by 15-28% (Figure 5). If choosing to sow early, reduce the associated risk by selecting a variety with improved disease resistance and mid to late flowering characteristics, and be vigilant with early disease monitoring and control.

Figure 4. Biomass production (t/ha) of field pea and vetch varieties with varying phenology sown across two times of sowing (ToS 1 = 2 April, ToS 2 = 4 May), at Eudunda 2020. Bars labelled with the same letters are not significantly different (P<0.05). 20mm of supplementary irrigation was provided via dripper irrigation in-furrow immediately post-April sowing and pre-May sowing within a couple of days to simulate a singular rainfall event.

Figure 5. Grain yield (t/ha) of field pea and vetch varieties with varying phenology sown across two times of sowing (ToS 1 = 2 April, ToS 2 = 4 May), at Eudunda 2020. Bars labelled with the same letters are not significantly different (P<0.05). 20mm of supplementary irrigation was provided via dripper irrigation in-furrow immediately post-April sowing and pre-May sowing within a couple of days to simulate a singular rainfall event.

Vetch

Time of sowing for vetch is dependent on the target end-use. Early sowing is important for grazing and green or brown manure, allowing the crop to establish early while the soil is warm. Time of sowing for hay production is dictated by when the cutting and drying window is likely to occur for a given variety, while early canopy closure is important to suppress weeds. Variety response to time of sowing was varied due to differences in phenology characteristics (Figures 4 and 5). For example, the very early maturing vetch variety Studenica benefitted from later sowing, as sowing too early exposed early pods to cold and frost, while the later maturing variety Morava benefitted from early sowing. Volga showed the greatest stability in production across time of sowing in low rainfall environments.

Disease management

The Australian pulse industry experiences losses of $74 million per year from disease infection, with the highest disease losses occurring in field pea and chickpea (Murray and Brennan 2012). Fungicide seed dressings and multiple foliar applications are highly recommended for both crops, as there is currently no varietal resistance to Ascochyta blight. However, fungicide application is generally not economical in low rainfall environments where grain production potential is low.

Disease infection risk can be low in pulse crops in low rainfall environments. However, regular crop monitoring and disease management strategies are still important as severe disease infection can occur in seasons with higher rainfall if left unmanaged. The best approach to disease management is integrated disease management, combining the selection of a resistant variety, use of clean seed, paddock hygiene, and the application of fungicides if required. It is important to implement a three to four year break between crops of the same type, revise variety selections and avoid sowing in paddock(s) in close proximity to the previous year’s crops (Blake et al. 2019). Crop sowing guides and GRDC Grow Notes provide key information on variety resistance characteristics and disease management approaches.

Herbicide use in lentil

Herbicide choice, rate and application timing is important to reduce risk associated with lentil production. Lentil is extremely sensitive to Group 5 (previously Group C) herbicide use in dry conditions. Applying herbicide prior to sowing is considered a lower risk option than a post-sowing pre-emergent (PSPE) application. Herbicide application incorporated by sowing (IBS) will disperse the herbicide so that it does not sit close to the seed, thereby reducing risk of crop injury. In contrast, herbicides applied PSPE can leach into the seed bed in low rainfall environments with the first rainfall event post application. It is important to follow all label rates and directions for use to minimise risk of crop injury. Crop injury from herbicides can result in reduced nitrogen fixation, more weed competition, reduced grain yields, and increase the risk of soil erosion over summer.

Broadleaf weed control options have expanded with the availability of Reflex® (Group 14; previously Group G), particularly for the control of weed populations that have developed resistance to imidazolinone (IMI) herbicides. It is important to understand the interaction between Reflex and Group 5 chemicals with specific soil types prior to using this product. Greater crop injury has been observed in alkaline soils compared to acidic sands (Bruce et al. 2022).

Conclusion

Pulse agronomy research and validation field experiments are continuing across South Australia with the aim to refine agronomic strategies for each rainfall zone, drive and support the continued expansion of areas grown to pulses and close the current yield gap. We will continue to see agronomic strategies refined, new varieties released to the market, and new herbicide tolerance traits becoming available in pulses. For this reason, it is important to stay up to date with pulse agronomic and variety information, and to evaluate variety selection each season to ensure the greatest yield potential. Be vigilant with disease monitoring and ensure fungicide applications are made ahead of rain events to minimise the spread of disease spores. Ensure herbicide label rates and directions for use are followed to reduce risk of crop injury. With careful and considered planning and management, pulse crops can be a profitable option for growers in the low to medium rainfall zone.

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support.

References

Blake S, Farquharson L, Kimber R, Davidson J, Walela C, Hobson K (2019) Ascochyta blight in intensive cropping of pulses. Proceedings GRDC Grains Research Update, Adelaide.

Bruce D, Roberts P, Day S, McMurray L, Walela C (2021) Flipping the script on the 'failure bean' story: faba bean out-yielding in early sown opportunities. 20th Australian Agronomy Conference, Toowoomba.

Bruce J, Aggarwal N, Sherriff S, Trengove S, Roberts P (2022) Crop safety and broadleaf weed control implications for various herbicides and combinations in lentil. Eyre Peninsula Farming Systems 2021 Summary, SARDI. Minnipa, South Australia, pp.126-132.

Day S, Oakey H, Roberts P (2019) A systems approach to break crop selection in low rainfall environments. 19th Australian Agronomy Conference, Wagga Wagga.

Day S, Roberts P, Gutsche A (2021) Low rainfall pulse production – one pulse does not fit all. Proceedings GRDC Grains Research Updates, Wudinna.

Murray G, Brennan J (2012) The current and potential costs from diseases of pulse crops in Australia. GRDC.

Roberts P, Walela C, McMurray L, Oakey H (2019) South Australian pulse research update – multi-season results. Proceedings GRDC Grains Research Update, Adelaide.

Contact details

Sarah Day

70 Farrell Flat Road, Clare SA 5453

0409 109 285

Sarah.Day@sa.gov.au

@Sarah_Day_

GRDC Project Code: UOA1702-019WSX, DAV1706-003RMX, UOA2105-013RTX,