FABA BEANS FOR THE CENTRAL-WEST AND NORTH-WEST PLAINS REGIONS OF NSW

| Date: 06 Sep 2010

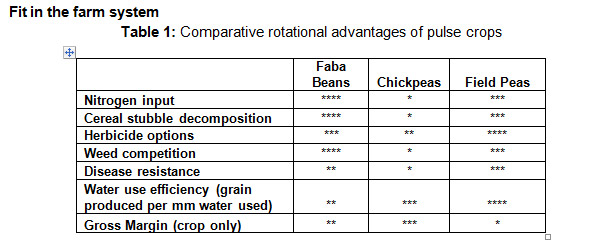

The benefits of pulses in a rotation are well understood. Faba beans are a superior break crop to chickpeas when comparing the rotational benefits in isolation from gross margins. Table 1 shows the relative benefits of faba beans as compared to other pulse options for similar soil situations.

Faba beans have the added benefit in that they also complement the logistical challenges of the broad acre farming systems of the region. Faba beans provide an option to plant early (late March to late April) and harvest early (late September to mid October), which will broaden the windows of sowing and harvest. This ensures that operations are still carried out in a timely manner for higher income crops.

The major drawback of faba beans as a rotation crop is that the one year gross margin (not taking any rotational effects into account) is generally much lower than can be expected from chickpeas.

There are conflicting reports about the resistance of faba beans to the root-lesion nematode (RLN) species Pratylenchus thornei; but unlike chickpeas, faba beans are resistant to the other RLN species Pratylenchus neglectus.

The extra yield of a wheat crop following a pulse crop (compared to wheat following wheat) can be due to the amount of plant available water (PAW) left unused by the pulse crop. Being a high biomass crop with deeper root penetration, faba beans generally use more water than chickpeas and field peas, therefore leaving less residual PAW for the following wheat crop.

In general, faba beans are a low cost rotational crop option, for which producers should only expect moderate income from the grain production of that particular crop.

While this paper focuses on the north-west and central-west plains region, there also appears to be potential for increased faba bean plantings on deep soils east of Dubbo, such as in the Coolah and Merriwa districts. The principles outlined in this paper will be the same for those districts, but a number of the specific details may be different, especially with regard to sowing time and disease management.

Paddock selection

Faba beans require moderately deep soil and at least 80mm of (PAW) at sowing (to a depth of 1m). 80mm of PAW is equivalent to approximately a 50% profile on a deep clay soil, but closer to a 75% profile on a loam soil. Faba beans have good tolerance of sodic and waterlogged soils, providing the sodicity or underlying structural problems do not greatly affect the water-holding capacity of the soil.

Being a lower return pulse crop, faba beans appear best suited to paddocks that have severe root/crown disease pressure, low nitrogen status or high grass weed pressure. Where none of these factors are significant, chickpeas will generally be a more profitable pulse option (at current prices).

Variety selection

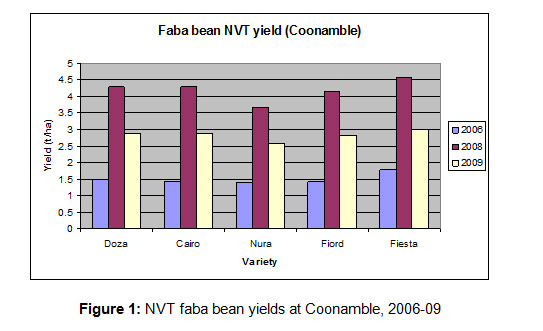

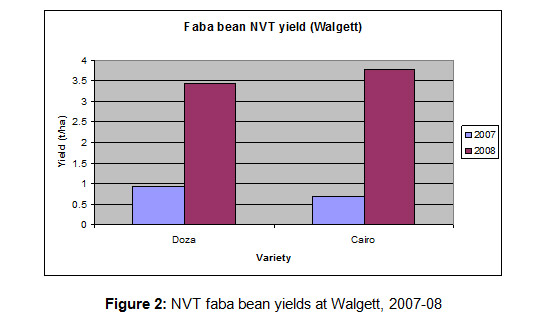

Cairo was the first variety released by the northern node of the Pulse Breeding Australia (PBA) faba bean breeding program. Doza was released in 2008, with the benefits over Cairo being improved rust resistance and quicker maturity. The only downside is a reduced seed size compared to Cairo , but seed size consistency is generally superior. For this region, Doza is currently the recommended variety. Faba beans are being targeted as a low input rotational crop option, and Doza fits into that scenario better than Cairo , due primarily to its superior disease resistance.

Sowing time

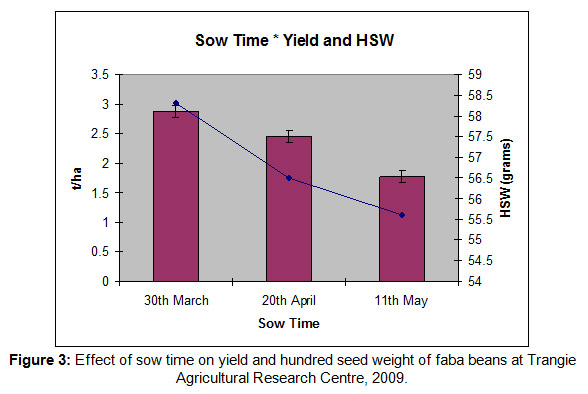

In the past 2-3 years, many growers in the north-west have experimented with sowing faba beans in late March/early April, often with considerable success. A trial was set up at Trangie Agricultural Research Centre in 2009 to test 2 released and 4 unreleased varieties across a range of sow times. The sow times were:

• 30th of March

• 20th of April

• 11th of May

Figure 3 shows that yield (averaged across all varieties) was highest from the early sowing time, with yield decreasing significantly from sow time 1 (2.87t/ha) to sow time 2 (2.46t/ha), and again from sow time 2 to sow time 3 (1.76t/ha). Hundred seed weight (which generally correlates to grain size) was also significantly greater from the early sowing than from the later sowings.

Previous recommendations have pointed to sowing faba beans in the Macquarie Valley from about the 25th of April, and from about the 10th of April for the Coonamble/Walgett regions. Despite of this, commercial crops and trials (albeit limited) in the past 2-3 years have had best results when planted in late March/early April. Based on these recent results, there appears potential to move the sowing window forward approximately 15 days for both regions, provided producers are willing to accept the increased risk of frost and diseases (especially rust and virus). Further research and commercial experience in the coming seasons will seek to more clearly determine optimal sow times for the region.

Faba beans can be sown deep into moisture (similar to chickpeas). Being a large seed it generally requires more moisture than other crops to germinate, so it is recommended to sow at a depth of at least 8cm so as not to expose the seed to fast drying surfaces.

Inoculation

Trials at Coonamble and Walgett in 2009 showed no response to inoculant application on those particular trial sites (heavy clay soils), likely due to rhizobia survival from naturalised vetch populations and possibly the movement of rhizobia in flood water. Despite of this, it is impossible to be sure that the rhizobia are present across a whole paddock or region, so inoculation with Group F inoculant is recommended.

Plant population

For faba bean crops sown on time, 15 plants/m² is generally considered a sufficient population, especially in areas where crops rely on stored moisture. This equates to a sowing rate of approximately 80-85 kg/ha for Doza (assuming a seed weight of 50 g/100 seeds).

Recommended row space is from 50-75cm. Wide rows reduce early water use, and are recommended when sowing early and where in-crop rain is likely to be low.

Pest and disease management

Pest and disease management are the most dynamic factors of faba bean production, and success in these areas will depend largely on having a good understanding of the major pests and pathogens involved.

The main diseases for the region are

• Rust (Uromyces viciae-fabae)

• Chocolate Spot (Botrytis fabae)

• Viruses (e.g. Bean leaf roll virus and Bean yellow mosaic virus)

The main insect pests are

• Aphids (as vectors of viruses)

• Heliothis (Helicoverpa spp.)

Rust

Rust infection is favoured by temperatures above 20ºC with 6 hours of leaf wetness (Hawthorne et al. 2004). This can make it a potential issue in this region both in autumn/early winter, as well as late winter/spring.

The primary control option for rust is to grow a relatively resistant variety, with the most resistant variety being Doza . There is no complete resistance to rust in faba bean varieties, so monitoring of crops and weather conditions is still important, and an early spray of mancozeb (with a grass spray) may reduce disease pressure in late winter/spring.

Chocolate spot

Chocolate spot infection is favoured by temperatures in the range of 15-25ºC, coupled with humid conditions (>70%) that continue for 4-5 days (Hawthorne et al. 2004). Both Doza and Cairo only have low levels of resistance to Chocolate spot, and the early mancozeb spray for rust will also control early infections of chocolate spot. Crops and weather forecast should then be monitored closely through the season to determine the need for any further applications. Wide rows will also help improve aeration and potentially reduce disease infection.

The appearance of ‘brown spots’ on leaves, stems and pods is a common result of abiotic stress in faba beans. These brown spots can be caused by factors such as spray oil damage and mechanical damage, and need to be clearly distinguished from Chocolate spot. Accurate disease identification needs to be carried out before a fungicide program for Chocolate spot is implemented.

Aphids and viruses

While there are many viruses that affect faba beans in this region, two of the major viruses are Bean leaf roll virus (BLRV) and Bean yellow mosaic virus (BYMV). Both viruses survive summer on green legume plants (such as lucerne), and can only infect through aphid vectors. Chemical control may prevent infection of BLRV, as the aphid needs a relatively long period to feed on the plant and transmit the virus. Chemical control will not have any effect on the fast transmitted BYMV. There are no current guidelines for the application of aphicides on faba bean to control virus. Early sowing (while maximising yield) will increase the exposure of crops to aphid flights, potentially resulting in more virus infection.

Cultural controls are the first options to be implemented. These include:

• Sow even plant stands into standing stubble.

• Control weeds that host aphids, including around perimeter and in neighbouring paddocks.

• Avoid sowing faba beans in paddocks adjacent to legume pastures/forages.

• Avoid stresses that reduce crop vigour (e.g. late sowing into cold soils, excessive herbicide application, poor nutrition)

• Block faba bean paddocks together and limit aphid entry points into paddocks

The breeding program has several lines that have higher resistance to viruses than Doza and Cairo . These breeding lines are classified as being ‘resistant’ to viruses, rather than being ‘immune’, so cultural control will still be important.

Helicoverpa spp.

Human consumption markets have low tolerance of damaged seed, so the Helicoverpa spp. threshold for this market is generally considered to be 1 larvae/m². The threshold for stockfeed markets is around 2-4 larvae/m².

The key to successful management involves regular crop monitoring and spraying larvae when small. Stoddard et al. (2009) says that late sowing also significantly increases crop exposure to Helicoverpa spp. in the podding stage, so early sowing may potentially have a place in reducing the level of damage caused by Helicoverpa spp.

Weed control

Sow thistle is the major broadleaf weed affecting faba beans on the soil type that they are commonly grown in this region. There are no post-emergent herbicide control options for sow thistle, so control primarily needs to be in preceding cereal crops, combined with pre-emergent herbicides and vigorous plant stands. Simazine is not strong on sow thistle and control will generally be greater when using other Group C chemicals such as metribuzin (Sencor), diuron or terbuthylazine (Terbyne). Other broadleaf weeds to be aware of include turnip weed and fleabane. Imazethapyr (Spinnaker) could be considered in combination with a Group C herbicide to improve control of turnip weed.

There are several herbicide control options for grass weeds both pre- and post-emergent. Being early maturing, there is also potential to use a crop-topping/desiccation spray or windrowing to sterilise annual ryegrass seed.

The vigour and early planting of faba beans means they are better able to compete with grass weeds than chickpeas, and weed escapes will set fewer seeds in a faba bean crop than in a chickpea crop.

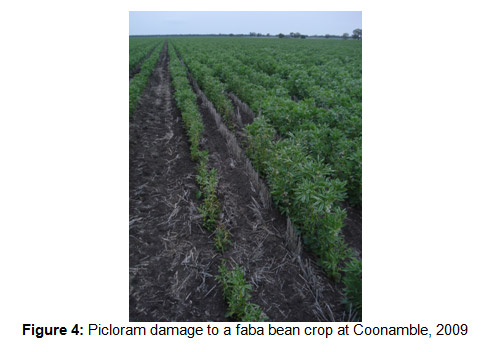

Faba beans are sensitive to several residual herbicides and plant back periods need to be adhered to. A number of cases of Group I herbicide damage were evident in 2009, with the main chemical involved being picloram applied in the 2008-09 fallow.

GRDC Project Code: UA00097,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK