The quality versus quantity debate

Author: Stuart Clarke (GrainCorp Operations Ltd) | Date: 19 Mar 2015

Take home messages

- Feed grain prices are likely to have greater variability than those of human consumption grades.

- The price spread between feed grain and human consumption grain will be driven by how much of each there is available domestically.

- Price implications should also be included when deciding on producing specific feed grades (i.e. don’t focus only on agronomic factors).

Introduction

This paper explores the recent trend where growers are making the decision to maximise yield rather than seeking the premiums associated with higher quality grain. This decision can be made in the management practises used or adoption of feed specific varieties. Typically this decision is focused on the yield advantages and rarely considers the marketing implications.

This paper looks at the price implications of the grain produced and any differences in the market of feed grain and human consumption grains. This paper does not look into agronomic or yield factors which also need to be considered.

Background

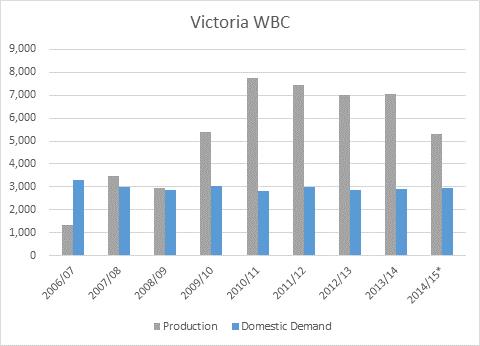

Victoria’s significant domestic demand typically consumes between 2.8MMT and 3MMT of wheat, barley and canola annually. This is split approx. 60% stockfeed (dairy, pig, beef and poultry feeding industries) and 40% human consumption and industrial (flour milling, malting and oilseed crushing). Domestic demand has been relatively stable over the past five years even with the variability in production that has been faced (Figure 1). Any residual grain above domestic consumption will be exported or carried through to the following season.

Figure 1. Production and domestic demand for Victorian wheat, barley and canola over the last nine years.

Due to the impact grain quality has on the end product produced, the feed segment and the human consumption markets value certain quality attributes differently. Stockfeed consumers are typically looking for cereals with high metabolisable energy (best identified through test weight) and low screenings. Most other attributes are of less significance. In comparison, human consumption processors place a higher importance on varietal characteristics, falling number, protein and germination (barley).

Due to this, some farming operations have taken the view that their resources are better focused on increasing yield and targeting the domestic feed sector rather than seeking the premiums associated with higher quality grain. This strategy has merit, especially at times when there is minimal price disadvantage for feed grades relative to the human consumption grades.

How price spread is determined

To determine the possible price implications between human consumption grades and feed grades, we should refresh ourselves on how price is determined and the role it plays in determining the flow of grain.

The relativity of supply and the demand for a grain, will dictate the flow of grain and ultimately the price. Any disparity in the two will cause a price response to solve the disparity. Price is how the market discourages supply and encourages demand to clear oversupply, or discourages demand and encourages supply to ration limited supply.

Domestic market versus export market

Domestic consumption will either expand or contract due to the price of grain, but as we have seen in Figure 1, the ability for the domestic demand to vary greatly is limited. Any residual grain above domestic consumption will seek demand and find its way into the export market or be carried forward.

Conversely, if there is less than ample grain supply to meet domestic consumption, price will rally to a point where either new supply is encouraged (i.e. inter region flows, interstate imports or international imports) or enough demand is deterred (i.e exports) to free up sufficient stock to meet demand.

Export parity

The value at which the export market will pay for each quality segment (export parity) again depends on supply and demand. The following factors are crucial in determining export parity:

- The quality profile of the exportable surplus,

- the volume and quality of supply from competing origins, and;

- the level of demand and at what price level demand can change or find substitutes.

The market will move toward or away from export parity to encourage or discourage supply, and therefore, export parity plays a big part in determining the price the domestic market needs to pay to secure that grain.

Now looking at the specifics between the two segments

Australia is typically a supplier of premium quality grain products aimed towards human consumption markets due to our climatic conditions, varieties grown, quality control and reliability. The efficiencies gained by the end user due to these attributes often allow Australian grain to command a premium over products without those attributes from competing origins. End users pay up to the amount gained by the efficiency of using premium quality Australian grain before they are better off using alternative sources. Having said this, many consumers are inelastic to Australian origin grain due to the difficulties in changing to a cheaper substitute.

Global stock feed producers on the other hand, are usually more elastic or sensitive to price, and willing to switch to the cheapest source of energy. A global stock feeder has more ability to switch and to manage less desirable quality attributes without disruption. The value they place on Australian origin above that of competing origins is less.

This means that Australian feed grain exports often have strong competition from lower cost producing countries and alternative feedstuffs (such as corn, dried distillers grain (DDG), meal). On the other hand the milling grades destined for export are relatively well supported due to the inelastic nature of the consumer and the added efficiencies those consumers realise.

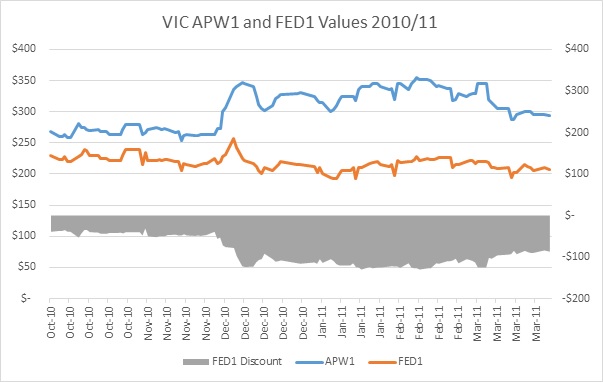

Over-supply of feed grain situation

During seasons with higher volumes of feed grains, the price spread between the grain produced for the human consumption market and that aimed at the stockfeed market is much larger. This is evident in years, such as 2010/11, where Australia has experienced a large feed wheat crop due to harvest rainfall (Figure 2). During this season production of feed wheat outstripped domestic consumption and the price dropped to a level where it was competing with corn in the feed rations of South East and North Asia. In the same season, milling grades were in short supply with prices rising to discourage export and ensure the domestic market, which valued the grain more, was supplied.

Figure 2. Price spread of wheat sold for the human consumption market and the stockfeed market during the 2010/11 season.

Under supply situation

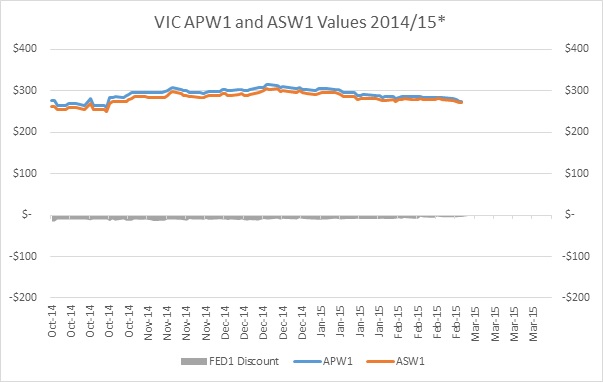

The current 2014/ 2015 season is a good example of the other end of the market. Feed wheat and low grade milling wheat have narrowed relative to the higher milling wheat (APW1 and H2) values (Figure 3). This is due to a larger than normal proportion of higher quality grades and a below average supply of lower quality wheats within the east coast. Domestic markets are now supporting the feed grain price in order to encourage supply or discourage demand. Milling grades are seeing the reverse as the market is seeking to encourage demand or discourage supply.

This is an example of the market solving the shortage of feed grades and the excess of milling grades, with the market starting to feed APW1/H2 in some areas.

Figure 3. Price spread of wheat sold for the human consumption market and the stockfeed market during the 2014/15 season.

Exceptions to the rule

One factor that can distort the above is changes in import regulations. One current regulation change that affects Victorian grain growers is the Chinese feed import restrictions. China’s demand for feed barley has increased significantly over the past two years, partly due to import restrictions affecting corn imports. In November 2013 China prohibited imports of US corn varieties containing a GM genetic trait named MIR162. This restriction effectively deterred all imports of US corn to China. To cover this loss of supply (approx. 5MMT in 2013 prior to the ban), Chinese private traders have turned to more expensive alternatives that are still allowed to be imported. These included Australian feed barley and Australian sorghum amongst others.

As demand for Australian barley into China has increased at the expense of US corn (a significantly cheaper alternative) it has significantly changed the flows of grain, and ultimately the price. Australian feed barley exports were traditionally destined for the Middle East markets, where competition is fierce from cheap alternatives. Now Australian feed barley is destined for China where it has little competition to contend with. This has changed demand and subsequently the price of a feed grain, but due to the nature of the restriction, it can be removed as quickly as it was implemented.

Conclusion

The following points can be taken away:

- The price spread between the two segments will be driven by how much of each there is available domestically.

- If there is an over-supply of feed grains, they typically have to compete into cheap export markets, meaning weak relative prices.

- If there is an under-supply of feed grains, the market will solve the shortfall by rallying the feed grain price to a level where it brings on more supply, converging towards milling grade values.

- Feed grain prices are likely to have greater variability than those of human consumption grades.

- By growing feed grades specifically a farmer is reducing the potential markets that could support that grain segments price, and opening up to more elastic consumers.

- Ultimately, price implications should also be included when deciding on producing specific feed grades (i.e. don’t focus only on agronomic factors).

Contact details

Stuart Clarke

GrainCorp Operations, Level 28, 175 Liverpool Street Sydney 2000

02 9325 9100

sclarke@graincorp.com.au

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK