Fleabane ecology and control in cropping systems of southern Australia

Author: Ben Fleet and Gurjeet Gill | Date: 12 Feb 2013

Ben Fleet and Gurjeet GillSchool of Agriculture, Food & Wine, University of Adelaide

GRDC project code: UA00105

Keywords: fleabane, summer fallow, weed management, stored soil moisture

Take-home messages

- Fleabane is a problematic summer weed that has increased in prevalence across many SA cropping districts in recent years.

- Herbicide control of fleabane is difficult because it has a natural tolerance to herbicide uptake and is often targeted over summer when plants are well established and spray conditions are not favourable.

- Field trials showed that fleabane control was significantly better where a 2nd knock of paraquat was applied, particlulary when the 1st herbicide application provided >60% control.

- Contrary to research in the eastern states, glyphosate at robust rates provided greatest control. However, glyphosate resistance in fleabane has already been detected and this approach maybe short lived.

Introduction

Flaxleaf fleabane (C. bonariensis) has been a problematic weed in the southern Queensland and northern New South Wales cropping regions for some time, however it has recently emerged as a difficult to control weed in South Australia, Western Australia and Victoria.

Fleabane thrives in no-till farming systems where germination conditions are favourable with most seeds germinating from the top 1cm of soil. Deep burial of seeds with cultivation maybe seen as a possible control option, however these seeds can remain viable, only to germinate when returned to the surface with later tillage.

Fleabane is capable of large seed production with individual plants being able to produce up to 120,000 seeds. These small light weight seeds can easily be dispersed over large areas by strong winds and water runoff assisted by a pappus on the seed, similar to sow thistle. Managing the seedbank of fleabane can be difficult as adjacent areas (i.e. neighbouring paddocks, roadsides and other non-cropped areas) are often a continual source for replenishment. Fleabane has a natural tolerance to the uptake of herbicide, a result of high trichome density on the leaf surface, a thick cuticle and low stomatal density. In addition control is made even more difficult as plants are often targeted soon after harvest by which time they have a well developed root system and spray conditions are often far from ideal.

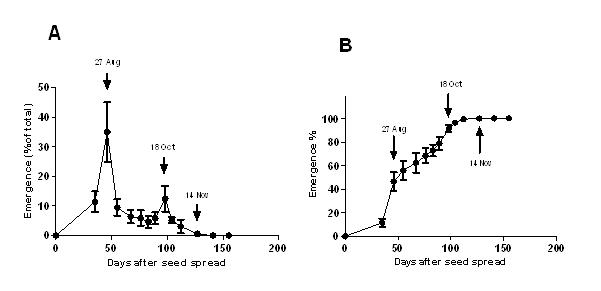

The ecology of fleabane has been studied in the eastern states where it was found to have no innate dormancy and germination was mostly light and temperature dependent. Germination was shown to occur at temperatures between 10-25oC, however 20oC is optimal. In Queensland fleabane can emerge as early as May with most seedlings recruited by the end of autumn and early winter. In southern New South Wales it emerges through winter and early spring, whereas recent studies have found that populations from South Australia emerge as late as August to November, provided moisture is not limiting (see Figure 1). In cropping fields, there could be considerable adaptive value in delayed germination in spring as it can grow rapidly and take advantage of the crops diminishing competitiveness. Hence, by harvest, fleabane can be well established, making control more difficult. Experience from the eastern states has been that it is much easier to control small plants than well established plants. Even smaller plants can be difficult to control if they have a well developed root system. Therefore given fleabane’s ecology, the following management strategies could be used for controlling before summer fallow:

- in crop application of residual herbicides to provide initial control of early cohorts;

- a late 2,4-d application; or

- crop topping with glyphosate near harvest when crop canopies are more open.

However, more research is required to evaluate the efficacy of these options.

Figure 1. (A) expresses fleabane establishment as a percentage of total germination starting from 17th of July 2012 when seed was spread. (B) demonstrates cumulative fleabane establishment as a percentage of total.

Small fleabane seedlings often go unnoticed by growers until after harvest, by which time fleabane is well established. Consequently most herbicide evaluations undertaken in SA have focused on controlling fleabane during the summer fallow period.

In 2010 a fleabane trial was undertaken at Bute, where different herbicide and surfactant options were evalauted for summer fallow control (data not shown). Trial results clearly showed that most herbicides used by growers provided inadequate control of fleabane. The best herbicide mixture was glyphosate + 2,4-D amine + metsulfuron (and oil surfactant) which provided only 60% control.

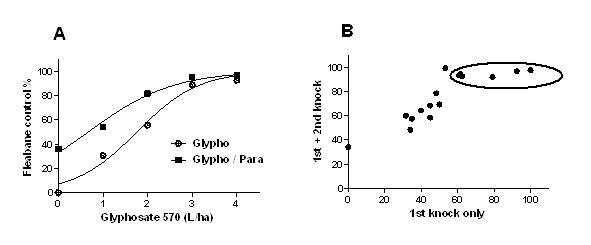

More recent trials undertaken last year at Bute and Pinnaroo evaluated several herbicide mixtures with and without a second knock of paraquat. A knife roller was also evaluated, however it was found to provide no additional control (data not presented). Results from both sites are summarised in Table 1. The trials showed that higher levels of control could be achieved with glyphosate + 2,4-D amine + metsulfuron, or glyphosate + dicamba, or glyphosate + 2,4-D amine & picloram, when followed by a robust second knock of paraquat. However, lower rates of glyphosate alone, glyphosate + clopyralid, or glyphosate + either carfentrazone or saflufenacil, were inadequate even with the second knock. Carfentrazone similarly to oxyflurofen (in 2010) showed very little activity on fleabane, whereas saflufenacil did result in extremely rapid burn out of fleabane. However this did not last and fleabane quickly recovered. In contrast to results from the eastern states, glyphosate alone at more robust rates (3L / ha or greater 570g active) was found to provide good levels of control even when a second knock was not implemented (Figure 2A). Despite these positive results with glyphosate as a standalone herbicide treatment, this strategy may be short-lived, as populations of fleabane resistant to glyphosate have been found in SA , NSW and Qld.

Applications of of paraquat were also only effective when the initial herbicide application provided ³60% control (Figure 2B).

Table 1. Shows herbicide efficacy on fleabane from the final assessment (mid April 2012) for main herbicide treatment alone (1st knock) and with the addition of a subsequent paraquat application (+2nd knock). Data was pooled from both Bute and Pinnaroo sites. Bute site: knife roller 11 Jan, 1st knock 12 Jan, 2nd knock 9 Feb; Pinnaroo: knife roller and 1st knock 1 Feb, 2nd knock 16 Feb.

Herbicide Treatment | Fleabane control % | |

1st knock alone | + 2nd knock | |

Untreated | 0 | 36 |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 1L / ha | 30 | 54 |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 2L /ha | 55 | 82 |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 3L / ha | 89 | 95 |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 4L /ha * | 93 | 97 |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 1L + 2,4-D amine (700g/L) @ 1.1L / ha | 50 | 87 |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 1L + 2,4-D amine (700g/L) @ 1.1L / ha | 50 | 84 ** |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 1L + Metsulfuron (600g/kg) @ 5g / ha | 50 | 73 |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 1L + 2,4-D amine (700g/L) @ 1.1L + Metsulfuron (600g/kg) @ 5g / ha | 57 | 91 |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 1L + Amitrole (250g/L) @ 2.8L / ha | 63 | 80 |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 1L + Dicamba (500g/L) @ 0.5L / ha | 46 | 69 |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 1L + Dicamba (500g/L) @ 1L / ha | 58 | 91 |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 1L + Carfentrazone (400g/L) @ 45mL / ha | 32 | 53 |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 1 L + Saflufenacil (700g/L) @ 18g / ha *** | 29 | 45 |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 1L + 2,4-D amine & Picloram (300g/L & 75g/L) @ 0.7L / ha | 50 | 97 |

Glyphosate (570g/L) @ 1L + Clopyralid (300g/L) @ 0.3L / ha | 42 | 69 |

P<0.001 LSD = 10.934 | ||

2nd knock herbicide application was Paraquat (250g/L)@ 2.4L / ha. The surfactant LI 700 @ 300mL / ha was used with all herbicide treatments except where indicated. * Only at Bute site, ** 2nd knock was Fluroxypyr (400g) @ 400mL / ha, *** Bonza surfactant used instead of LI 700 The above treatments are for research purposes and some may not be registered | ||

Figure 2. (A) fleabane dose response for glyphosate alone and with additional application of paraquat @ 2.4L / ha (2nd knock). (B) fleabane control of standalone herbicide treatment (1st knock) against control from both 1st and 2nd knock for each treatment across Bute and Pinnaroo trials.

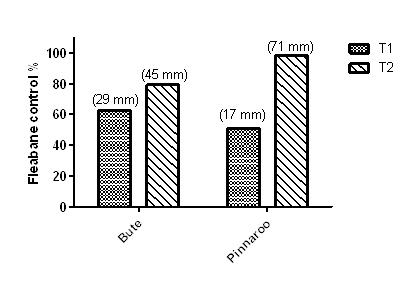

The impact of fleabane control on stored soil moisture was also assessed in April for a selection of treatments at Bute and Pinnaroo (Figure 3.). These results clearly showed that when fleabane was effectively controlled considerable soil water could be retained for the following crop.

Figure 3. Fleabane control as a percent at each site is displayed in the columns, with saved soil moisture above that of the control plots displayed in brackets. Where T1 = glyphosate + 2,4-D amine + metsulfuron; T2 = glyphosate (3L / ha) as standalone treatments. Soil moisture was measured to a depth of 1.2m.

Residual herbicides that provide early control of fleabane in spring as well as late herbicide applications (i.e. crop topping) appear to provide the best opportunity for control. Furthermore, applying these effective, but sometimes expensive herbicide options in summer fallow using precision spray technologies (i.e. WeedSeeker® or WEEDit® systems) will help minimise herbicide inputs and costs, without compromising weed control and profitability.

AcknowledgementsResearch reported here on fleabane was undertaken in a current GRDC funded project (UA00105).

Contact detailsBen Fleet,

University of Adelaide

(08) 8313 7950

GRDC Project Code: UA00105,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK