Viable growth in the pulse industry

Author: Ron Storey (Profarmer Australia) | Date: 16 Feb 2016

Background

2016 is the United Nations International Year of the Pulse. And with chickpeas and lentils trading at around $1000 per tonne or better in 2015, it’s a great time to talk pulses. Are these levels sustainable? Most likely not, but the long term outlook for pulses remains positive.

An updated and more detailed presentation will be available on the day of the GRDC Grains Research Update and will include references to data which is currently being released around the recent launch of the International Year of the Pulse. This paper therefore is an outline of the key themes which will be covered in the presentation.

Key themes

Global Pulse Overview – who’s who in the zoo?

The global pulse trade is largely represented by chick peas, field peas and lentils. In context, world wheat production is 600-700 million tonnes (Mt), whereas chick pea is 11-12Mt, field peas 10-11Mt, and lentils 5Mt. In global terms, pulses are a niche crop. One could describe the more unique pulse products (such as blackeye beans, adzuki beans) as boutique crops.

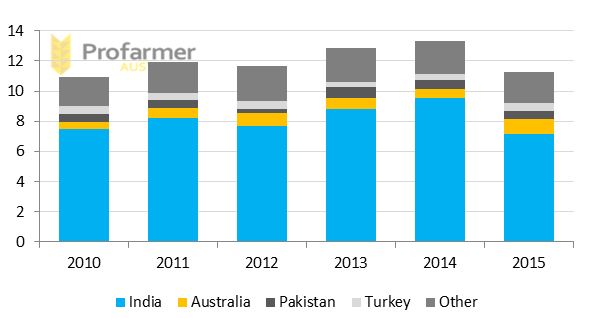

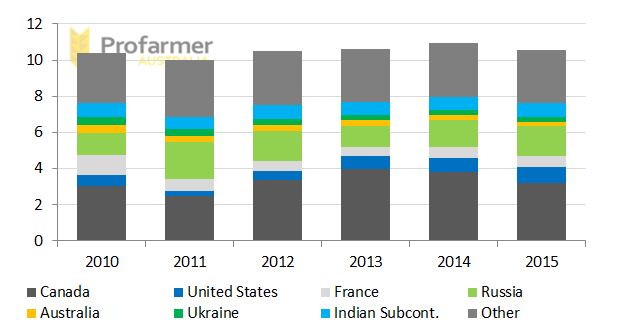

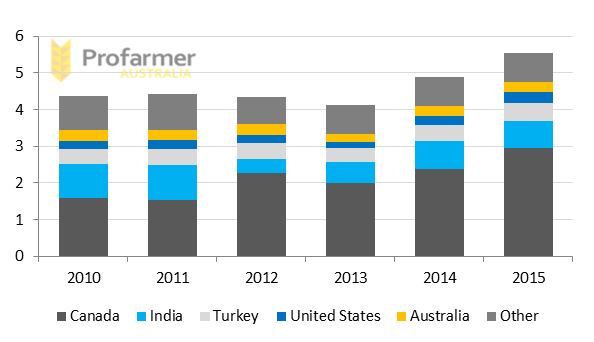

The major producers are detailed in the charts below (Figures 1-3). A bird’s eye view is that India dominates chickpea production, field pea producers are more diverse (with Canada and Russia the big ones), and lentils dominated by Canada. On the world stage, Australia is a relatively small producer.

Figure 1: World chickpea production (Mt). (note: countries read from bottom to top in the graph).

Figure 2: World field pea production (Mt). (note: countries read from bottom to top in the graph).

Figure 3: World lentil production (Mt). (note: countries read from bottom to top in the graph).

Australian production

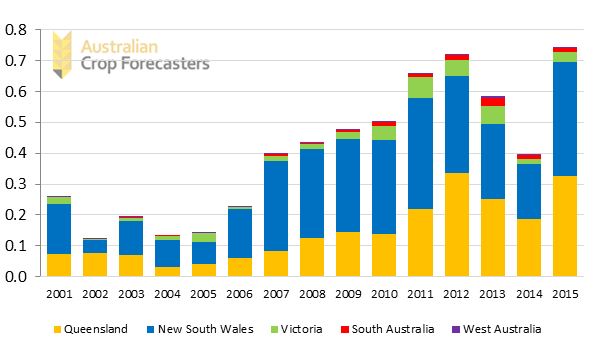

Australian chickpea production has grown five-fold in the last decade approaching one million tonnes, with Queensland and New South Wales (NSW) leading the way (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Australian chickpea production by state (Mt) (note: states read from bottom to top in the graph).

Australian field pea production has been stable at around 300,000 tonnes, South Australia (SA) being the largest producer (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Australian field pea production by state (Mt) (note: states read from bottom to top in the graph).

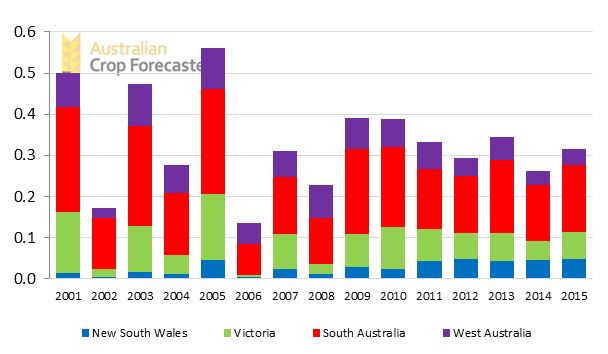

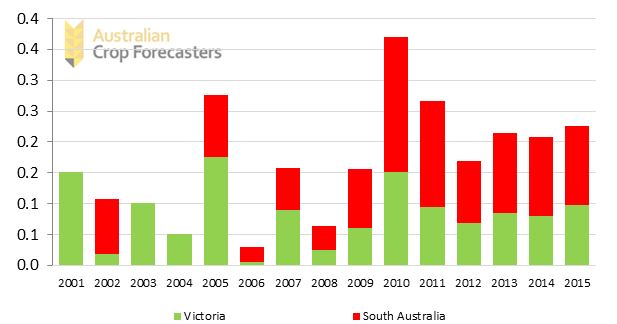

Australian lentil production has been relatively stable at around 250,000 tonnes with SA and Victoria being the home ground (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Australian lentil production by state (Mt).

Customers and competitors

Customers

The Indian sub-continent, encapsulates the customer demand story. While there are clearly other markets, including China, the global pulse trade pulsates according to what is happening in India, which is a combination of India’s local weather and crop as well as domestic politics around food supply, affordability and security.

Competitors

Australia is the number one world exporter of chickpeas at 600-900,000 tonnes in recent years. Canada dominates trade in field peas and lentils with exports averaging around three million and two million tonnes, respectively. In contrast, Australia’s field pea and lentil exports average 150,000 and 250,000 tonnes, respectively.

Pulse prices – a story of volatility

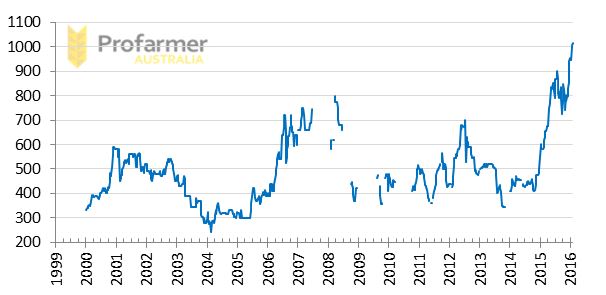

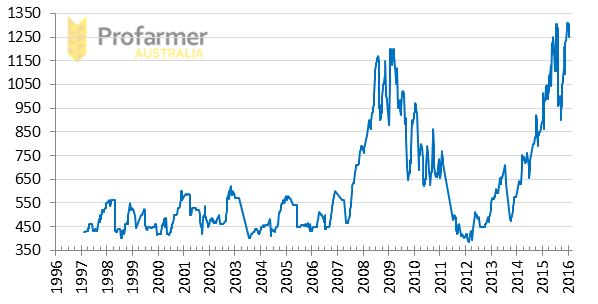

Figures 7, 8 and 9 show the price range and volatility of pulses over the last decade. The price swings can be violent both intra and inter season, and are largely a factor of real and perceived demand in the Indian sub-continent, where the monsoon rains dictate market sentiment. Short-term price spikes and dips can occur as Indian governments (federal and provincial) juggle the need for price stability and food security for its vast population, as well as pricing to local farmers to incentivise local production. Similarly, import policies by other consuming nations (such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, China) have at times had a material impact on price stability and contract execution for exporters and producers.

The rapid rises in chickpea prices over 2015 have been driven by a poor local crop in India due to poor monsoon rains (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Brisbane chickpeas.

Lentil prices in 2015, like chickpeas, have responded to the poor local crop in India (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Port Adelaide lentils.

Field pea prices have followed in sympathy with the general price rises in chickpeas and lentils. In a sense, field peas are the ’poor cousins’ in the pulse trade as they become a substitute in human diets when chickpeas and lentils become too expensive, and find a home as a protein source for stockfeed (replacing soybean meal) when prices are lower (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Port Adelaide field peas.

Pulse marketing – similarities and differences to cereals

In the GRDC GrowNotes series there is a marketing chapter which contains the core principles which apply to any grains, oilseeds and pulses marketing. It also has commodity-specific information for each crop. Refer to GRDC GrowNotes.

During the presentation at the GRDC Grains Research Update, we will highlight those aspects of pulse marketing which are the most important to maximise profitability for growers. We will also explore the key concepts that growers should be aware of when deciding between base commodity marketing compared to a value-added or paddock to plate model.

2016 International Year of the Pulse

Will the 2016 International Year of the Pulse trigger a shift towards plant protein as a diet alternative to animal protein, driven by water, energy usage and health benefits?

This is a fascinating question in the context of what happens in the ‘protein story’ over the next 10-20 years, and what part pulses might play in helping to deal with the world’s food security challenge.

There is no debate regarding the growing middle classes of Asia and their rapidly increasing demand for higher protein foods. This is typically described in terms of more poultry, pork, beef, lamb and dairy products. In turn, this means more grain demand, as the conversion ratio to animal protein from grains ranges from around 2-3kg grains for 1kg poultry to 5-6kg grains for 1kg beef. This is a good news story for grains, as it equates to more demand.

But there is another story as well, based around cost, environmental, and resource sustainability in relying solely on animal protein. This involves statistics around the number of litres of water consumed in producing a kilogram of animal protein compared to plant protein; the greenhouse emissions produced from animal protein production; and the energy requirements of animal protein versus plant protein.

And then there are the health concerns of increased consumption of meats in societies which have rapidly increasing health costs from diseases which appear to be potentially diet-related?

This will never be a question of either/or. But it may well be a question of balance, and what part pulses can play in providing a more balanced and cost-effective source of protein to a world population which currently faces a food security and health challenge.

The International Year of the Pulse in 2016 will hopefully have much more to say and provide a fact-based conversation on diet and sources of protein. It may well lead to a trigger point for substantial transformation of the image and place of pulses in the global food solution.

Conclusion

- World pulse production is a niche crop compared to the big guns of cereals and oilseeds

- Globally, Australia is a small pulse producer, but a large exporter of chickpeas

- India sets the pace in pulse markets; first, second and third

- Pulse prices are volatile, even more so than the mainstream cereals and oilseeds

- Pulse marketing has some unique traits to be aware of compared to base commodity marketing

- 2016 is the International Year of the Pulse: it could trigger some fundamental shifts in the world’s approach to solving the protein demand, food security, and environmental sustainability questions.

Useful resources

Pulse Australia Website - Year of the Pulses 2016

Contact details

Ron Storey

NZX Profarmer

L1, 616 St Kilda road, Melbourne VIC 3004

61 418 332431

ron.storey@nzx.com

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK